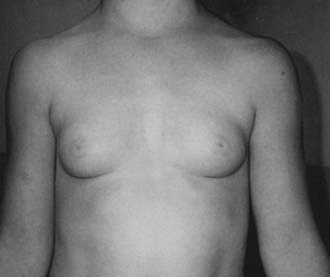

FIGURE 121-1. Typical appearance of premature thelarche in a  -year-old girl.

-year-old girl.

Pathophysiology

The precise cause of premature thelarche remains unknown, although several theories about its pathogenesis have been proposed. These include individual differences in peripheral sensitivity to estradiol, as well as an alteration in the ratio of estrogen to androgens from increased sex hormone–binding globulin levels.18 Gain-of-function mutations in the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) receptor or Gsα have been hypothesized to be a cause of premature thelarche, although a search for molecular genetic abnormalities in these patients has been negative thus far.19 Most cases of premature thelarche are characterized by an FSH-predominant response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) stimulation testing.20 However, it is still unclear whether this indicates involvement of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis in causing this condition because this response is also characteristic of the prepubertal state in young girls.21–24 One likely hypothesis is that premature thelarche exists along a continuum of hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian activity, representing one end of a clinical spectrum that, in some patients, manifests as full-blown central precocious puberty characterized by a luteinizing hormone (LH)-predominant response to GnRH stimulation.24 What governs whether activation of this axis is mild, partial, transient, or complete remains a mystery. It is interesting to note that premature thelarche is relatively common in girls, whereas prepubertal gynecomastia is uncommon in boys, and both FSH and estradiol levels are higher in girls than in boys at all ages.25

Natural History

Follow-up studies of patients with premature thelarche have indicated several possible scenarios in terms of clinical course. Complete regression of breast tissue occurs in a substantial percentage of girls with premature thelarche, particularly in girls with onset before age 2.26 In other patients, breast tissue may persist, or even enlarge, although initial studies failed to identify an increased risk of pubertal progression or additional medical problems.13,27 In some series, as many as 14% of girls with classic premature thelarche progress to central precocious puberty, although baseline clinical and biochemical characteristics of these patients are indistinguishable from those whose condition remains stable.21,28 It is reassuring that adult stature and the timing of central puberty appear to be normal in girls with nonprogressive premature thelarche.29

Management

In girls with typical premature thelarche, reassurance and follow-up are all that are indicated. Careful clinical assessment, including determination of growth velocity, should be performed at 3 to 6 month intervals. A bone age radiograph is helpful at the time of diagnosis and is reassuring if it is consistent with the chronologic age. Additional radiographs are indicated if there is evidence of secondary sexual progression or acceleration of linear growth. Because of the possibility of progression to central precocious puberty, it is recommended that follow-up by a pediatric endocrinologist or the primary care physician continue. Other causes of breast masses in children include fibroadenomas, abscesses, hemorrhagic cysts, and, rarely, metastatic disease.30

PREMATURE PUBARCHE

Clinical Features

Premature pubarche is characterized by the development of pubic hair in prepubertal children. Additional findings often include axillary hair, body odor, and mild acne.14,31 Most cases of premature pubarche are secondary to premature adrenarche, which is characterized by mildly elevated serum adrenal androgen levels, especially dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, for age, with values corresponding to the degree of Tanner stage development.32,33 Premature adrenarche usually occurs in children between the ages of 6 and 8 but may occur earlier. Additional diagnostic criteria include the absence of other signs of puberty, such as breast development. Although growth velocity and skeletal maturation may be slightly advanced, significant virilization such as clitoromegaly, voice change, or increased muscle mass is absent.34 Because premature pubarche can be the presenting sign in congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) or virilizing adrenal or gonadal tumors, these conditions should be considered and excluded.

Pathophysiology

Attempts to define the precise clinical and biochemical profile of premature adrenarche have yielded significant heterogeneity in terms of underlying pathophysiology and concurrent metabolic features. Physiologic adrenarche, which occurs normally during midchildhood, refers to the development of the zona reticularis and an associated increase in adrenal androgen secretion.35,36 This is accompanied by alterations in adrenal enzyme activity, characterized by increases in 17,20-desmolase and 17-hydroxylase enzymes and a decrease in 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity.37,38 Although much progress has been made in understanding the physiology of adrenarche, the driving force behind this process, in both premature and physiologic adrenarche, remains unknown. Differences in peripheral metabolism of adrenal androgens have been implicated as a contributing factor in some patients, supported by the finding of elevated 3α-androstenediol glucuronide, a marker of peripheral adrenal androgen activity, in children with premature adrenarche compared with controls.33,39 Partial adrenal enzyme deficiencies, including 21-hydroxylase, 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, and 11-hydroxylase deficiencies, have been reported at variable frequencies among patients presenting with premature adrenarche,40–44 whereas the prevalence of heterozygosity for 21-hydroxylase deficiency has been found to be increased in this population.45,46 A search for genetic markers associated with premature adrenarche has revealed sequence variants in a number of genes encoding for steroidogenic enzymes and related receptors, although the functional consequence of these variants is unclear.47,48 Last, a subset of patients has been identified with steroid hormone profiles intermediate between those with “typical” premature adrenarche and those with CAH, a condition described as “exaggerated adrenarche.”49 An increased incidence of premature adrenarche has been noted in children with a history of central nervous system insult such as head trauma or hypoxic-ischemic injury, suggesting that a central process may play a role in its development.

Natural History

Despite the fact that children with premature adrenarche experience a normal onset of central puberty and achieve normal adult height,50,51 the historical assumption that this developmental variation was “benign” has proved to be incorrect. For many children, premature adrenarche may now be thought of as one stage in a continuum of metabolic abnormalities that ultimately manifests as syndrome X, which is typified by insulin resistance, hyperandrogenism, and dyslipidemia.52 Indeed, as many as 45% of girls with premature adrenarche may develop polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) later in life.53 Even lean girls with premature adrenarche have demonstrable alterations in body composition and insulin and androgen levels when compared with controls.54 Insulin resistance has been reported in boys with premature adrenarche, suggesting that a propensity for future development of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes pertains to both genders with this condition.55,56 Prenatal growth restriction resulting in low birth weight has been established as a common risk factor for premature adrenarche, functional ovarian hyperandrogenism, and hyperinsulinemia, implying that these metabolic derangements may be related via a shared primary abnormality.57 However, identifying predictive factors in patients who will develop hyperandrogenism in later life thus far have eluded detection.58 Further biochemical and molecular genetic characterization of patients with premature adrenarche and its postmenarchal corollaries should yield greater understanding of pathogenesis and allow improved diagnostic discrimination and prognostic accuracy.

Management

In patients with isolated pubic hair and normal linear growth, a bone age radiograph may be the only diagnostic study indicated,31 although the finding of normal or only mildly elevated adrenal androgens provides additional reassurance. Further investigation, including baseline or stimulated serum adrenal androgen and steroid precursor levels, is warranted if there is marked growth acceleration, advanced skeletal maturation, clitoromegaly, or other significant virilization on physical examination. Patients with typical premature adrenarche should be monitored at 3 to 6 month intervals to allow determination of growth velocity and clinical status. Because the condition is progressive, most patients experience a gradual increase in body hair over time, accompanied by a normal rate of skeletal advancement. It is recommended that girls be monitored until menarche and a pattern of regular menses has been established because of the increased incidence of functional ovarian hyperandrogenism in this population. Accumulating evidence suggests an important role for metformin in the treatment of hyperandrogenism and hyperinsulinism during adolescence. Insulin sensitization with metformin early after menarche in girls with premature adrenarche appears to prevent the progression of PCOS.59 Metformin has also been shown to improve adipose body composition and may delay puberty in prepubertal girls with premature pubarche and history of low birth weight.60,61 However, to date there is no evidence that pharmacologic intervention in premature adrenarche is indicated, especially because we are not yet able to predict which children will develop more serious adverse associations.62

Pubic Hair of Infancy

Pubic hair of infancy is a unique entity that has been described in both boys and girls. Typically, infants have isolated pubic hair growth, usually in an atypical location such as the scrotum in males and the mons in females. Linear growth, skeletal maturation, and laboratory evaluation are otherwise normal. Pubic hair tends to resolve spontaneously before the age of 1 year. Given that long-term follow up of these patients is not available, it is unclear whether there are any clinical consequences for children with this developmental variant.63,64

Pathologic Precocious Puberty

CENTRAL PRECOCIOUS PUBERTY

Also termed gonadotropin dependent, central precocious puberty (CPP) refers to early activation of the HPG, and thus “central,” axis. The underlying physiology of this form of precocious puberty therefore is identical to that of normal puberty, with the distinction being that it occurs at an abnormal time and may be the result of a pathologic condition.

Clinical Features

Girls with CPP typically present with breast enlargement and other estrogenic changes accompanied by growth acceleration and skeletal maturation. Unlike puberty that begins at a normal age, in CPP, dissociation is often noted between gonadarche and adrenarche, which may be a result of lower adrenal androgen levels during early childhood. Testicular enlargement, which is the first sign of CPP in boys, often goes unrecognized, with subsequent genital and body hair development prompting medical evaluation.

Pathophysiology

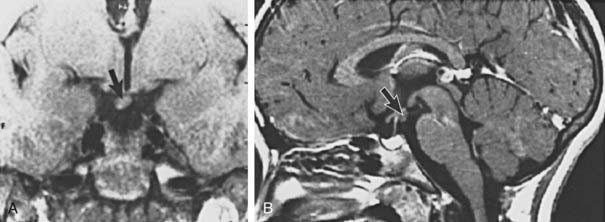

Causes of CPP can be divided into two general categories. Idiopathic CPP is used to designate cases in which no anatomic abnormality is identified, whereas in the remaining cases, a central nervous system insult, either congenital or acquired, is believed to be the trigger. CPP is far more common in girls than in boys, with as many as 90% of cases designated as idiopathic.65 This is in contrast to the frequency of idiopathic CPP in boys, which is reported to account for 10% to 50% of cases.66 Idiopathic CPP is thought to result from alterations in one of the different excitatory and inhibitory neuroregulatory pathways of GnRH secretion. Familial precocious puberty is common, occurring in up to 27% of families of children with CPP with an apparent autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance implicating a genetic origin in a significant numbers of patients with CPP.67 CPP in one patient was traced to a mutation in the GPR54 gene.68 However, a search for GPR54 polymorphisms in a study of Chinese girls with CPP revealed no functional abnormalities.69 Several forms of intracranial lesions have been implicated as causative of CPP, the most common of which is a hypothalamic hamartoma, a heterotopic mass located typically in the region of the tuber cinereum70 (Figs. 121-2 and 121-3). This congenital malformation consists of GnRH-secreting neurons or transforming growth factor α–producing astroglial cells, both of which are believed to function as ectopic triggers on the hypothalamic pulse generator, resulting in an escape from the normal central nervous system inhibitory constraint on pubertal onset.71,72 Rarely, hypothalamic hamartomas are associated with an increased incidence of seizures, particularly gelastic, or laughing, seizures.73 Other central nervous system abnormalities that are associated with CPP include hypothalamic-pituitary or optic chiasm tumors, pineal or suprasellar cysts, septo-optic dysplasia, neurofibromatosis, head trauma, and hydrocephalus.74,75 The mechanism of intracranial abnormalities that leads to precocious puberty is believed to be caused by a disruption of the neural pathways that normally exert tonic inhibition on the brain in terms of activation of puberty. This process results in a seemingly paradoxical situation in which many disorders associated with deficiencies of anterior pituitary hormones may be associated with excessive gonadotropin secretion. There is concern, yet no definitive proof, that exposure to environmental estrogens may lead to the development of CPP. High serum levels of the mycoestrogen zearalenone were detected in one study of girls with CPP. Mycotoxin-exposed girls had accelerated growth and weight gain, which is postulated to result from the growth promoter effect of these agents caused by their biochemical resemblance to anabolic agents used in animal breeding.76

FIGURE 121-2. Tanner stage III breast development in a 6-year-old girl with a hypothalamic hamartoma. Bone age was  years, pubic hair was Tanner stage I, and the vaginal mucosa was estrogenized.

years, pubic hair was Tanner stage I, and the vaginal mucosa was estrogenized.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CPP is based on the ability to detect activation of the HPG axis, during which sensitivity to stimulation is increased at each level of the axis. The GnRH stimulation test takes advantage of the fact that a “primed” pituitary gland responds to GnRH with a brisk elevation of gonadotropins, which in turn stimulates gonadal sex steroid secretion.77 Historically, synthetic GnRH (Factrel) was used for the evaluation of CPP. However, this agent is not available in the United States. Although several different protocols have been developed, the most widely used is the GnRH agonist stimulation test with multiple blood sampling, in which nafarelin or leuprolide is used.78,79

A pubertal response to GnRH stimulation is classically characterized by a pattern of LH predominance indicating an elevation of LH above that of FSH, whereas a prepubertal response is marked by a minimal increase in LH, if any, but may elicit an FSH response above baseline. An intermediate response, typified by an FSH-predominant response, is seen in early central puberty and in premature thelarche. A caveat of the various available tests is their inability to differentiate early central puberty from normal. This stems in part from wide variability, poor reproducibility, and lack of age-based references for the various available gonadotropin assays. Additional evaluation of patients with CPP typically includes a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain to rule out an intracranial lesion.80A bone age radiograph provides important information about the degree of skeletal maturation and remaining growth potential. Pelvic ultrasonography is useful in documenting uterine and ovarian enlargement, ovarian symmetry, or the presence of cysts or other ovarian abnormalities.81 In patients with a prepubertal or suppressed response to GnRH stimulation, further investigation for causes of peripheral precocious puberty is indicated.

Treatment

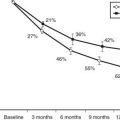

Potential negative consequences of precocious puberty include compromise of adult stature due to premature fusion of epiphyseal growth plates, and psychosocial issues related to a discrepancy between physical and emotional maturity. Therefore, the primary goal of therapy is to temporarily suppress the HPG axis to allow improved adult height and to simultaneously restore the child to a physiologic state comparable with that of his or her peers. The discovery of safe and effective treatment in the form of GnRH agonists revolutionized the therapy of CPP in the mid-1980s, and this is the treatment of choice for this condition.82,83 Although the mechanism of action of GnRH analogue therapy is not completely understood, it is believed that downregulation of pituitary gonadotroph receptors occurs as a result of sustained high levels of GnRH.84 Several long-acting GnRH analogues have been used in the treatment of precocious puberty, with subcutaneous, intranasal, and intramuscular routes of administration.85 The depot preparation of leuprolide acetate, given in the form of monthly intramuscular injections, is the most commonly used agent in the United States and has been shown to provide safe and effective long-term therapy in children with CPP.86–88 Reports of longer-acting formulations of GnRH analogues administered at 3 month intervals also appear promising,88,89 but these have not yet been well tested in children. A subcutaneous implant containing histrelin acetate that is replaced yearly is also available for the treatment of CPP. Studies have demonstrated marked suppression of LH and sex steroids with a good safety profile.90,91 Although untested, it is possible that GnRH antagonists may eventually have a role in the treatment of CPP as well.92 Therapy for CPP is characterized by suppression of gonadotropins below the pubertal range and a return of gonadal steroids to prepubertal levels, along with a deceleration of growth velocity and skeletal maturation. Therapeutic efficacy may be biochemically documented by gonadotropin suppression in response to GnRH testing, whereas pelvic ultrasonography represents a potentially useful tool for monitoring the effects of treatment in girls, which are characterized by regression of the internal genitalia from a pubertal to a prepubertal size.93 In boys, a decrease in testicular volume provides similar information. Although therapy has a profound impact on the outcome of many patients, a subset of patients with precocious puberty has been identified in whom height prognosis is quite favorable, even without treatment. These patients are characterized as having an indolent form of precocious puberty, in which pubertal progression occurs gradually and bone age advancement is minimal.94,95 Distinguishing features at presentation among this subset of patients include an increased height age/bone age ratio and predicted adult height similar to target height when compared with patients who have rapidly progressive precocious puberty.96

Therapeutic Outcomes

Several different outcome measures have been examined with regard to the safety and efficacy of GnRH analogue therapy for CPP, including adult height, bone mineralization, and resumption of puberty after treatment. Each of these is discussed individually.

Adult Height

Evidence is increasing to suggest that girls with onset of CPP before the age of 6 years have the best response to therapy with a height gain of 2.9 to 12.5 cm with GnRH analogues.95,97–100 Indications for GnRH analogue therapy other than CPP are not supported by current data.101

Bone Mineralization

The effects of sex steroids on bone density are well described, with peak acquisition of bone mass occurring during puberty.102 Reports of a rapid decrease in bone mineralization after GnRH analogue therapy in adults initially led to concerns about potential similar negative consequences of GnRH analogue therapy in children with precocious puberty. However, several follow-up studies have now demonstrated normal bone mineral density in adult patients previously treated with a GnRH analogue.99,103,104

Resumption of Puberty

Once pubertal suppression is removed via discontinuation of GnRH analogue therapy, spontaneous resumption of puberty occurs. Several studies have examined the onset of progression of secondary sexual development, as well as the age of menarche, in girls treated for precocious puberty with GnRH analogues. Results have indicated a resumption of pubertal LH pulsatile secretion in most patients within 4 months after therapy,105 as well as normal menarche, which on average occurs 18 months after treatment is stopped.100,106 It has been found that normal ovulatory cycles are established in this population within a time frame indistinguishable from that of the untreated adolescent.106 Similarly, gonadal function in adults previously treated with GnRH analogues for central precocious puberty appears to be normal.99,103

PERIPHERAL PRECOCIOUS PUBERTY

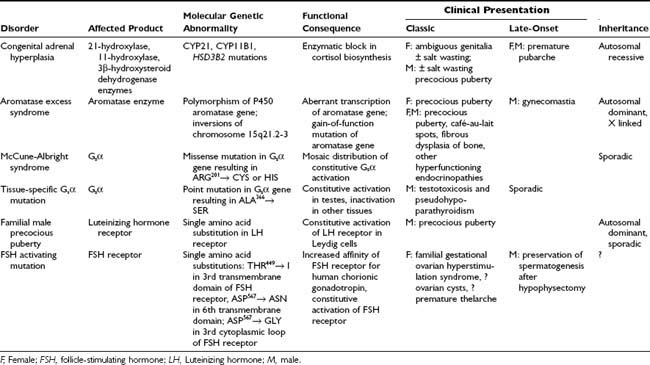

Also termed gonadotropin independent, peripheral precocious puberty refers to cases in which sex steroid exposure leads to pubertal development through a source other than activation of the HPG axis. This broad category encompasses an extremely heterogeneous group of abnormalities. Evaluation and differential diagnosis depend on whether the child is a girl or a boy, and on whether the clinical presentation reveals changes associated with estrogens, androgens, or both. Individual causes of peripheral precocious puberty are discussed here, and the genotype-phenotype relationships seen in these disorders are outlined in Table 121-1.

Abnormalities of Enzymes Involved in Steroid Biosynthesis

Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

CAH represents a group of diseases stemming from an autosomal recessive inherited deficiency of an enzyme required for adrenal steroidogenesis (see Chapter 103). The resulting disorders represent a wide spectrum of molecular genetic abnormalities and phenotypic characteristics. Excess adrenal androgen secretion as a consequence of CAH is the most common cause of abnormal postnatal virilization in children. The hallmark of these disorders is an enzymatic block in the cortisol biosynthetic pathway leading to lack of negative feedback stimulation at the level of the pituitary gland. The resulting increase in pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone and buildup of steroid precursors proximal to the enzyme block result in an “overflow” of these precursors to the androgen synthetic pathway with subsequent overproduction of adrenal androgens. Once the diagnosis has been made, glucocorticoid replacement is indicated to result in cessation of adrenal hyperstimulation and a return of adrenal androgens to near-normal levels. The three types of CAH that may result in abnormal adrenal androgen production and subsequent virilization in prepubertal children are 21-hydroxylase,107,108 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase,109 and 11-hydroxylase deficiencies.110 Typical physical findings in girls may include pubic and axillary hair, body odor, growth acceleration, advanced bone age, and clitoromegaly. However, not all these features may be present at diagnosis. Boys present with similar changes, including increased phallic size and increased muscle mass. Testicular volume, however, is in the prepubertal range, in contrast to that observed in central precocious puberty. Rare cases of CAH with adrenal rest tissue represent an exception, in which unilateral or even bilateral enlargement of the testes may be found.111

Aromatase Excess Syndrome

Aromatase is the enzyme responsible for the conversion of androgens to estrogen in many tissues, including the gonads and adipocytes. Increased aromatization has been reported to be a cause of familial and prepubertal gynecomastia.112 Kindreds have been described in whom the aromatase excess syndrome appears to be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, resulting in gynecomastia in boys and precocious puberty in girls, accompanied by elevations of estradiol and estrone.113 Aberrant expression of the P450 aromatase gene is thought to form the basis of the condition in at least one case,114 whereas an activating mutation in the aromatase gene has also been reported as a cause of familial aromatase excess.115

ABNORMALITIES OF G PROTEINS

McCune-Albright Syndrome

McCune-Albright syndrome (MAS), first described in 1937 by Albright and colleagues,116 is a rare disorder characterized by the clinical triad of precocious puberty, polyostotic fibrous dysplasia of bone, and café-au-lait spots (see Chapter 67). Molecular genetic investigation led to the discovery that MAS is caused by an activating mutation in Gsα, the stimulatory subunit of the G protein involved in intracellular signaling.117,118 This somatic mutation, which usually involves substitution of arginine for histidine or cysteine at the 201 position, is believed to occur in early embryogenesis, leading to a mosaic distribution of affected tissues. The result is a phenomenon of unregulated intracellular accumulation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate, which in turn stimulates downstream gene transcription.119 Hyperfunction of endocrine glands is a cardinal feature of MAS, with numerous organs potentially affected, including the adrenals, parathyroid glands, pituitary gland, thyroid, and gonads.120 Rare involvement of nonendocrine tissues has also been reported in MAS and has included hepatobiliary disease, cardiac disease, and sudden death.121,122 Unregulated sex steroid secretion from the gonads in prepubertal children forms the basis of precocious puberty in MAS, which, although it occurs in both sexes, is more commonly reported in females. In prepubertal girls, precocious puberty is characterized by sporadic ovarian cysts with subsequent elevations in serum estradiol levels. Spontaneous regression of the cysts can lead to withdrawal bleeding, whereas long-term unopposed use of estrogen can result in uterine breakthrough bleeding.

The clinical presentation of MAS is extremely variable, ranging from patients with extensive skin (Fig. 121-4) and bone involvement (Fig. 121-5) and progressive precocious puberty to patients with only mild manifestations. Increasingly, patients exhibiting a forme fruste of MAS are being recognized, in whom isolated involvement of bone,123 adrenals,124 or gonads may occur.125 The variable clinical presentation reflects, in part, the fact that the Gsα mutations that cause MAS are postzygotic and mosaic.119 Thus, different individuals and different organs within the same individual may contain variable proportions of cells that harbor the Gsα mutation. Tissue-specific imprinting of the GNAS-1 gene may contribute to the observed phenotypic heterogeneity.126 In patients with rapidly progressive precocious puberty, historical treatment has involved medroxyprogesterone or an aromatase inhibitor, such as testolactone. Unfortunately, these therapies have been largely disappointing.127 Although the newer generation aromatase inhibitor anastrozole was not shown to be beneficial in a study of 27 girls with MAS,128 therapy with letrozole appears to be more promising. In a study of 9 girls with MAS, a significant decrease in frequency of menstrual bleeding and rate of growth was observed.129 Another option is tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, which was shown to be safe and efficacious in 25 girls with MAS and precocious puberty.130 However, long term data are lacking. It remains to be seen whether pure estrogen receptor antagonists, such as Faslodex,131 will prove to be superior to existing treatments for the precocious puberty of MAS. Regardless of the pharmacologic agent used, the underlying disease process is unchanged. Once the onset of central puberty commences, the HPG axis may override the independent gonadal function, although persistent autonomous ovarian activity has been documented in postmenarchal girls and women with MAS and a history of precocious puberty.132

FIGURE 121-4. Café-au-lait skin pigmentation in a 4-year-old girl with McCune-Albright syndrome who presented with precocious puberty. The irregular borders of these lesions designate them as “coast of Maine” café-au-lait spots, as opposed to the smooth-bordered “coast of California” variety characteristic of neurofibromatosis. The propensity of these lesions to stop abruptly at the midline is demonstrated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree