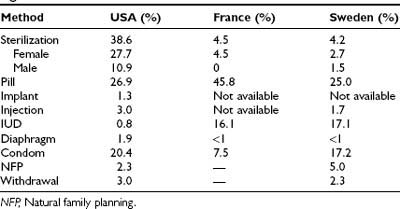

Patterns of contraceptive use vary across the world, and contraceptive choice depends on numerous factors. In the United States in 2002, over 38% of couples were sterilized, 27% were using the contraceptive pill, 20% condoms, and less than 1% of women used the intrauterine device (IUD).2 In contrast, for example, sterilization is much less common and IUD use much more common in France4 and Sweden,5 and many more women in France use the pill compared with women in either the United States or Sweden (Table 134-2).

Table 134-2. Contraceptive Use in the United States (1995),2 France (2000),4 and Sweden (1994)5 Among Women Aged 15 to 44 Years

Not only do patterns of contraceptive use vary between countries, but they also vary in the same country between different age groups and stages of life. In the United States in 2002, 13% of women aged 35 to 39 used the combined pill, compared with 32% of women aged 20 to 24.2 Use of progestogen-only injectable Depo Provera (depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate, DMPA) that is effective for 3 months has increased markedly in the last 10 years, particularly among adolescents, 4.4% of whom were using it in 2002.6 Contraceptive use also varies according to ethnicity and race, marital status and fertility intentions, education and income. Despite high prevalence of use of contraception, unintended pregnancy is common and so is induced abortion. While much of the decline in population growth has been achieved by contraceptive use, no country has achieved low fertility rates without access to abortion. In the United States, the abortion rate in 2001 was 45/1000 women of reproductive age (compared with around 15 in England and only 5 in the Netherlands), despite apparently widespread use of contraception. In a national survey of 10,683 U.S. women having an abortion in 2000/2001, 54% claimed to be using contraception in the month of conception, 28% condoms and 14% the pill.7 Women who were not using a method at the time of conception (46%) perceived themselves at low risk of pregnancy (33%), had experienced problems with contraception in the past, or had concerns about side effects (32%).

Currently available reversible methods of contraception fall into two broad categories: hormonal and nonhormonal. Certain issues are common to all methods.

EFFECTIVENESS AND EFFICACY

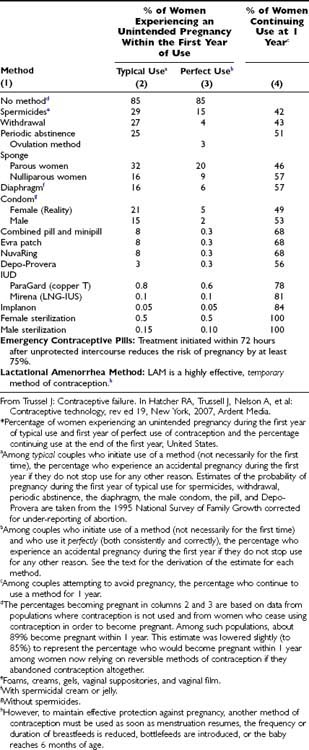

The effectiveness of a method of contraception is judged by the failure rates associated with its use. Failure rates for currently available methods are shown in Table 134-3.8 The rates are estimated from U.S. studies and show the percentage of couples who experience an accidental pregnancy during the first year of use of each method. The effectiveness of a contraceptive depends on its mode of action and how easy it is to use. Pregnancy rates during perfect use of a method reflect its efficacy. If a method prevents ovulation in every cycle in every woman, it should have an efficacy of 100%: if there is no egg there can be no conception. Only if a mistake is made or if the method is used inconsistently will a pregnancy occur. The contraceptive implant Implanon inhibits ovulation in almost every woman for 3 years. There have been very few pregnancies reported if Implanon has been correctly inserted. Failures that have occurred are often associated with the user either being overweight or using concomitant medication (e.g., an anticonvulsant) which reduces the absorption of contraceptive steroids. The combined pill is similarly very effective at preventing ovulation but only if taken correctly. Pregnancy rates for perfect use are around 1 in 1000; true failures are due to incomplete inhibition of ovulation, especially among women who metabolize the pill rapidly. Inhibition of ovulation, however, depends on the pill being taken daily for 21 days followed by a pill-free interval (PFI) of only 7 days. If pills are missed or the PFI prolonged (imperfect use), ovulation can occur. Unless a method is independent of compliance, like Implanon, use is rarely perfect, and the effectiveness of a method (as opposed to efficacy) is reflected by pregnancy rates during typical use (see Table 134-3). Pregnancy rates are still often described by the Pearl Index—the number of unintended pregnancies divided by the number of women years of exposure to the risk of pregnancy while using the method. However, in trials, failure rates of most methods decrease with time, since women most prone to failure fall pregnant early after starting use of a method. With time, a cohort of couples still using a method increasingly comprises couples unlikely to fall pregnant (because they are good at using the method, have infrequent sex, or are subfertile). So the longer the cohort is followed, the lower the pregnancy rate is likely to be. Furthermore, failure rates in most clinical trials are often underestimated because all of the months of use of the method are taken into account when calculating failure rates, regardless of whether or not intercourse has occurred during that cycle. For long-acting methods of contraception such as IUDs and implants, the pregnancy rate with time (cumulative pregnancy rate) is much more informative.

COMPLIANCE

Many couples using contraception do so inconsistently and/or incorrectly. Inconsistent or incorrect use accounts for the difference between perfect and typical-use failure rates. Some methods are easier to use than others. Because IUDs, the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (IUS), and contraceptive implants are inserted and removed by a health professional and are entirely independent of compliance for efficacy, their failure rates are accordingly very low (see Table 134-3). It is arguably the provider who falls short of perfection and not the user for these methods; typical and perfect use rates are almost the same. Imperfect use is rare—undetected uterine perforation during IUD insertion, for example. Depo-Provera lasts 12 weeks but still demands the motivation and organizational skills required to attend for repeat doses. Compliance with oral contraception is not easy. In one study, 47% of women reported missing one or more pills per cycle, and 22% reported missing two or more.9 In a study using electronic diaries to record compliance, 63% of women in the first cycle of use and 74% in the second cycle missed one or more pills.10 Poor compliance with, and discontinuation of, oral contraceptives together account for an estimated 700,000 unintended pregnancies in the United States each year. Typical-use failure rates are even higher with methods of contraception that rely on correct use with every act of intercourse (condoms, diaphragms, withdrawal, and natural family planning). The overestimate of the effectiveness of contraceptive methods tested in clinical trials is compounded by the reality that trial participants tend to use the methods more consistently and correctly than most users do in real life.

DISCONTINUATION RATES

In an international review of discontinuation rates after 1 year of use of hormonal contraception, rates varied from 19% (for Norplant) to 62% (the combined pill).11 Discontinuation rates are higher for methods that do not require removal by a health professional, as is clear from Table 134-3, which shows the percentage of couples in the United States still using each method at the end of 1 year. In the United States, 40% of married women and 61% of unmarried women using a reversible method of contraception change it over the course of 2 years.12 Some—especially those with more years of education—change from a less effective method to a more effective method. But many change to less effective methods; in a study of U.K. women having Implanon contraceptive implants removed, almost half changed to a less effective method.13 Adolescents are particularly likely to discontinue their contraceptive methods. In one study, 50% discontinued during the first 3 months of use. Reasons for discontinuation are often associated with perceived risks and real or perceived side effects.14 In the international review,11 the commonest reason for discontinuation was for bleeding dysfunction. In a Swedish study following up 656 women for 10 years,15 between 28% and 35% of women (depending on age) stopped taking the oral contraceptive pill because of fear of harmful side effects. Another 13% to 17% of them stopped because of menstrual dysfunction, 15% to 20% because of weight increase, and 14% to 21% because of side effects associated with mood change. Continuation rates are often regarded as a surrogate for acceptability of a method, but this is simplistic. A multitude of factors determine acceptability, and continuation of a method may only reflect that method being the best of a bad lot.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

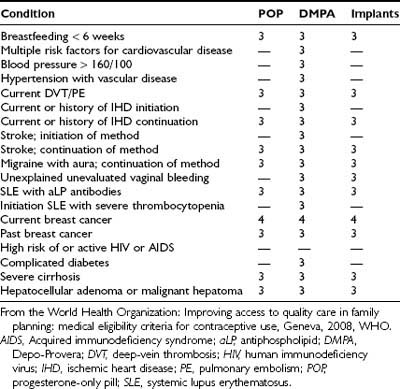

Pharmaceutical companies list endless cautions, warnings, and contraindications in their contraceptive product labels. Most contraceptive users are young and medically fit and can use any available method safely. A few medical conditions, however, are associated with theoretical increased risks if certain contraceptives are used, either because the method adversely affects the condition (the combined pill, for example, may increase the risk of a woman with diabetes developing cardiovascular complications) or because the condition or its treatment affects the contraceptive (some anticonvulsants interfere with the efficacy of the combined pill). Since most trials of new contraceptive methods deliberately exclude subjects with serious medical conditions, there is little direct evidence on which to base sound prescribing advice. In an attempt to produce a set of international norms for providing contraception to women and men with a range of medical conditions which may contraindicate one or more contraceptive methods, the World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a system to advise on medical eligibility criteria (MEC) for contraceptive use.16 Using evidence-based systematic reviews, the document classifies conditions into one of four categories. Category 1 includes conditions for which there is no restriction for the use of the method, whereas category 4 includes conditions that represent an unacceptable health risk if the contraceptive method is used (absolutely contraindicated). Classification of a condition as category 2 indicates that the method may generally be used but that more careful follow-up is required. Category 3 conditions are those for which the risks of the combined oral contraceptive pill generally outweigh the benefits (relatively contraindicated). Provision of a method to a woman with a category 3 condition requires careful clinical judgment, since use of that method is not recommended unless there is no acceptable alternative. For some conditions, distinction is made between starting the method and continuing its use. For example, a woman who is known to have ischemic heart disease (IHD) could start to use an LNG-IUS; it is a category 2 condition. However, if a woman already using an LNG-IUS develops IHD, then continued use of the contraceptive method is a category 3 condition (the theoretical risks outweigh the benefits unless no other method is acceptable/available). The regularly updated document is available on the web, and a system is in place to incorporate new data into the guidelines as it becomes available. Category 3 and 4 conditions for the IUD/IUS, combined hormonal contraception, and progesterone-only contraception according to the 2008 edition of the MEC are summarized in Tables 134-4, 134-5 and 134-6, respectively.

Table 134-4. WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria Category 3 and 4 Conditions for COC, Combined Contraceptive Patch, and Vaginal Ring

| Category 3 Conditions |

| Category 3/4 Conditions |

Diabetes with retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, other vascular disease or of more than 20 years’ duration. |

| Category 4 Conditions |

COC, Combined oral contraceptives; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism.

From the World Health Organization: Improving access to quality care in family planning: medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, Geneva, 2008, WHO.

Table 134-5. WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria Category 3 and 4 Conditions for the Copper IUD and LNG-IUS

| Category 3 Conditions for Both Copper IUD and LNG-IUS* |

| Category 4 Conditions for Both IUD and LNG-IUS |

AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; aPL, antiphospholipid; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; IUD, intrauterine device; PID, pelvic inflammatory disease; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

* There are a few conditions which are category 3 for the LNG-IUS only because of its hormone content: Acute DVT/PE; continuation of LNG-IUS in a woman who develops ischemic heart disease, migraine with aura, ovarian cancer, AIDS or pelvic TB; SLE with APL antibodies; severe cirrhosis, hepatocellular adenoma, and malignant hepatoma.

From the World Health Organization: Improving access to quality care in family planning: medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, Geneva, 2008, WHO.

HEALTH BENEFITS OF CONTRACEPTION

Most couples use contraception for over 30 years. Additional health benefits beyond pregnancy prevention offer significant advantages and influence acceptability. In a nationwide sample of 943 U.S. women, satisfaction with oral contraception was most likely among women aware of the noncontraceptive benefits of the pill and experiencing few side effects.17 In a study of young women starting the combined pill, those who benefitted from a reduction in preexisting troublesome dysmenorrhea were eight times more likely to continue using the pill than women who did not experience a similar benefit.18

Existing combined hormonal methods improve menstrual bleeding patterns and alleviate dysmenorrhea, acne, and sometimes premenstrual syndrome.19 The combined pill significantly reduces the risk of ovarian20 and endometrial cancer.19 Increasing numbers of women choose the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS Mirena) and DMPA because of the amenorrhea they confer. Perimenopausal women appreciate the option to continue using the LNG-IUS into the menopause when it can be used to deliver the progestogen component of HRT. Barrier methods, particularly condoms, protect against sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including cervical cancer. When contraceptives are being used for their beneficial side effects or in the management of a medical problem such as menorrhagia, the risk/benefit ratio (and medical eligibility criteria) changes.

Nonhormonal Methods

NATURAL FAMILY PLANNING

Although few couples in the developed world use so-called natural methods of family planning (NFP), in some parts of the world these methods are common. All involve avoidance of intercourse during the fertile period of the cycle (“periodic abstinence”). Methods differ in the way in which the fertile period is recognized. The simplest is the calendar or rhythm method in which the fertile period is calculated according to the length of the normal menstrual cycle. The mucus or Billings method relies on identifying changes in the quantity and quality of cervical and vaginal mucus. As circulating estrogens increase with follicle growth, the mucus becomes clear and stretchy allowing the passage of sperm. With ovulation and in the presence of progesterone, mucus becomes opaque, sticky, and much less stretchy or disappears altogether, inhibiting sperm transport. Intercourse must stop when fertile-type mucus is identified and can start again when infertile-type mucus is recognized. Progesterone secretion is also associated with a rise in basal body temperature (BBT) of about 0.5° C. The BBT method is thus able to identify the end of the fertile period. Other signs and symptoms such as ovulation pain, position of cervix, and degree of dilatation of the cervical os can be used to help define the fertile period. (For a detailed review of NFP methods see ref. 21.)

Many couples find periodic abstinence difficult. Failure rates of natural methods are high (see Table 134-3), mostly due to rule breaking. Perfect use of the mucus method is associated with a failure rate of only 3.4%. There is no evidence that accidental pregnancies occurring among NFP users, which are conceived with ageing gametes, are associated with a higher risk of congenital malformations.

The lactational amenorrhoea method (LAM) is used during breastfeeding. Amenorrhoea during breastfeeding provides more than 98% protection from pregnancy during the first 6 months postpartum if the mother is fully or nearly fully breastfeeding and has not yet experienced vaginal bleeding after the 56th day postpartum. Guidelines for LAM advise that as long as the baby is less than 6 months old, a woman can rely on breastfeeding alone until she menstruates or until she starts to give her baby significant amounts of food other than breast milk.22 Prospective studies of LAM confirm its effectiveness.23

BARRIER METHODS

The male condom is inexpensive, widely available without involving health professionals, and apart from occasional allergic reactions, is free from side effects. Polyurethane condoms were developed to overcome the disadvantages of traditional latex condoms (allergic reactions, impaired sensation during intercourse, short shelf life in certain storage conditions, and weakening with oil-based lubricants). Although less effective for contraception, polyurethane condoms offer an alternative for people with latex sensitivity. Condoms are effective in preventing STIs.24 Their use has increased significantly during the last decade as a result of concern over the spread of HIV and AIDS.

Female barrier methods are much are less popular. The diaphragm and cervical cap must be fitted by a health professional and do not confer the same degree of protection from STIs. Recent interest in the diaphragm has led to the development of new types of the device but with no added advantage with respect to efficacy or ease of use.25 There is little evidence to demonstrate that the concomitant use of spermicide increases the effectiveness of the diaphragm. The female condom covers the mucus membranes of the vagina and vulva and is more effective in preventing STIs but has a high failure rate and lower acceptability than the diaphragm.

Spermicide alone is not recommended for prevention of pregnancy; it is only moderately effective. Nonoxynol 9 (N-9) is a spermicidal product sold as a gel, cream, foam, film, or pessary for use with diaphragms or caps. Many male condoms are lubricated with N-9. Because frequent use of N-9 might increase the risk of HIV transmission, women who have multiple daily acts of intercourse or who are at high risk of HIV infection should not use N-9.26 For women at low risk of HIV infection, N-9 is probably safe.

INTRAUTERINE DEVICES

The intrauterine device is a safe and effective long-acting method of contraception. In the United States in the 1970s, some 10% of couples used the IUD; currently it accounts for less than 2% of contraceptive use.2 The decline in use resulted mainly from the reports of a number of deaths from sepsis among women using the Dalkon Shield.27 The IUD has remained an important method in many other countries in the developed and developing world and has, if anything, undergone a revival since the introduction of the LNG-IUS. A useful review of the world literature on all aspects of intrauterine contraception, including both copper and progestogen-releasing devices, was published as a supplement to the journal Contraception in 2006.28 Because of its potential duration of use, the copper IUD is an extremely cost-effective method of contraception, even in countries where the up-front cost of the device and its insertion is high. The TCu 380A is licensed for 10 years but is effective for at least 12.

Efficacy

In a study involving 7159 women years of use of the TCu 380A, the cumulative pregnancy rate after 8 years was 2.2 per 100 women years, not significantly different from that of female sterilization.29

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree