Fig. 7.1

Cardiovascular (CV) morbid and fatal events in normotension, white coat hypertension, and true hypertension with effective or noneffective (dippers and non-dippers) blood pressure reductions at night (From Verdecchia et al. [10], with permission)

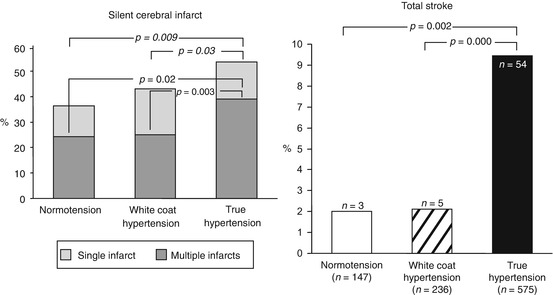

Fig. 7.2

Prevalence of silent cerebral infarcts and stroke in normotension, white coat hypertension, and true (sustained) hypertension (Modified from Kario et al. [11], with permission)

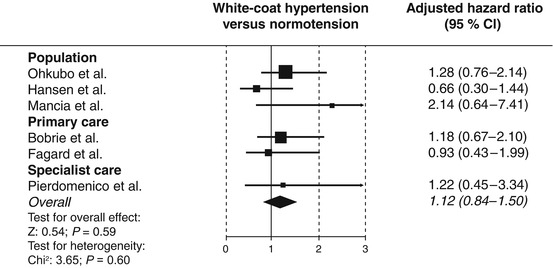

Fig. 7.3

Adjusted hazard ratios and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) of individual studies and overall analysis for the incidence of cardiovascular events in white coat hypertension compared to true normotension (From Fagard et al. [15], with permission)

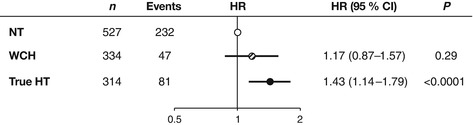

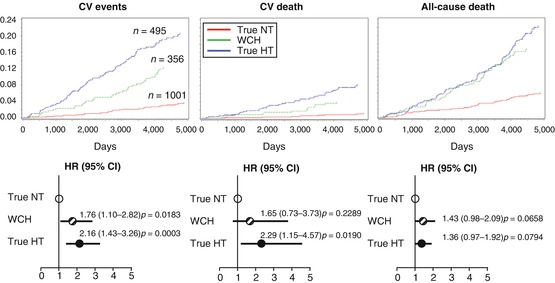

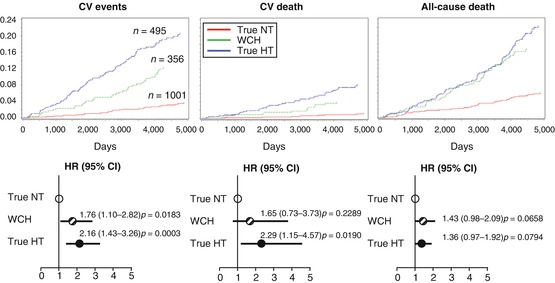

Fig. 7.4

Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) for cardiovascular events in untreated normotensives (NT), white coat hypertensives (WCH), and true (sustained) hypertensives (HT) in a large database (IDACO) from several sources. Hypertension consisted of an isolated systolic blood pressure elevation. Diagnosis was based on office and home blood pressure measurements (Modified from Franklin et al. [17], with permission)

7.3 White Coat Hypertension and Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality: Positive Reports

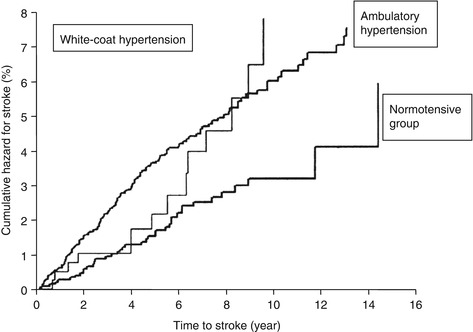

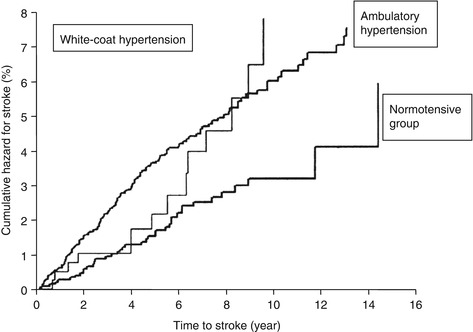

Few years ago Verdecchia et al. [18] reported the results of a meta-analysis of several studies in which a comparison was made between the incidence of stroke in truly normotensive subjects, white coat hypertensives, and individuals with an elevation of ambulatory blood pressure . Compared to truly normotensives, the incidence of stroke was from the beginning much greater in subjects with ambulatory hypertension. In contrast, the incidence of stroke did not differ between truly normotensives and white coat hypertensives over the first 4–6 years, after which the latter group exhibited a steep rise that made the stroke cumulative incidence superimposable to that of ambulatory hypertension over the remaining observation time (Fig. 7.5) [18]. The implication was that white coat hypertension is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events which takes time to become manifest and therefore can mainly be seen in studies with an adequate duration of the follow-up.

Fig. 7.5

Cumulative hazard for stroke in normotensive, white coat hypertensive, and ambulatory hypertensive subjects (From Verdecchia et al. [18], with permission)

A long follow-up of subjects with white coat hypertension has been made available by a few studies only [19, 20]. In the PAMELA study , cardiovascular morbid and fatal events were assessed from the initial examination in 1991–1992 to 2004 with an average observation period longer than 11 years [19]. As shown in Fig. 7.6, the cumulative incidence of cardiovascular morbid and fatal events increased progressively from true normotension to white coat and true hypertension, identification of the three conditions being based on office versus ambulatory blood pressure. In the white coat hypertensive group, the age- and gender-adjusted risk of morbid plus fatal or only fatal cardiovascular events amounted to 76 and 65 %, respectively, an increase that was less than that seen in true hypertension (+116 and 129 %) but that nevertheless differed significantly and substantially from what was seen in the true normotensive group. White coat hypertensives additionally showed a 46 % increase in age- and gender-adjusted risk of all-cause mortality that was of borderline statistical significance.

Fig. 7.6

The upper panel shows the Kaplan-Meyer curves for cardiovascular (CV) events, CV death, and all-cause death in true normotensives (NT), white coat hypertensives (WCH), and true hypertensives (HT). The lower panel shows the age- and gender-adjusted risk of these events, taking NT as reference. Data from the PAMELA study (Modified from Mancia et al. [19], with permission, and unpublished data)

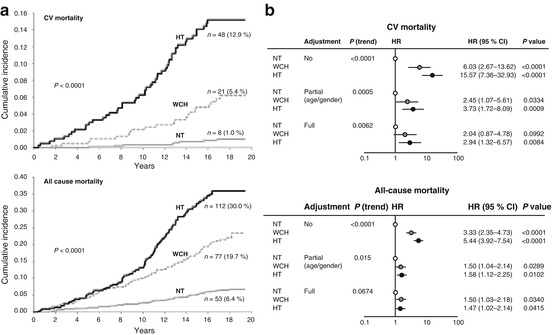

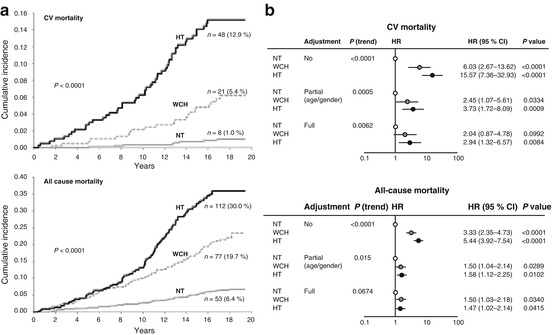

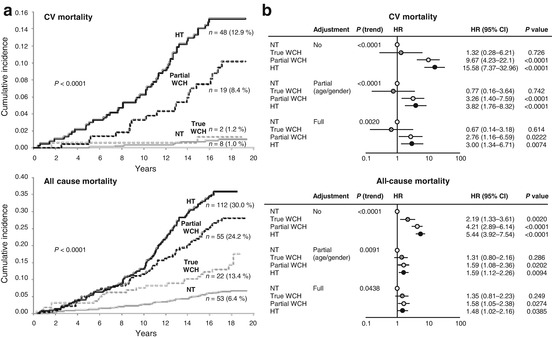

More recently, the follow-up of the white coat hypertensive subjects from the PAMELA population has been extended to an average of 16 years [21]. As shown in Fig. 7.7, over this long follow-up white coat hypertensives (diagnosed as done in clinical practice, i.e., by an elevation of office with a normal ambulatory or home blood pressure) continued to show an incidence of cardiovascular mortality that was intermediate between true normotensive and true hypertensive individuals. Compared to the normotensive group, the age- and gender-adjusted cardiovascular mortality risk was substantially greater, and the significance extended to fully adjusted data, i.e., to baseline variables reflecting metabolic factors and other clinical conditions, to indicate an independent contribution to prognosis of the elevated blood pressure values.

Fig. 7.7

(a) Cumulative incidence and (b) hazard ratio (HR) for cardiovascular (CV) and all-cause mortality in normotensives (NT), white coat hypertensives (WCH), and true hypertensives (HT) of PAMELA study over a long observation period (average 16 years). NT and true HT were defined by office, home, and ambulatory blood pressure normality and elevation, respectively. WCH was defined by elevation of office blood pressure and ambulatory or home blood pressure normality. Full adjustment refers to adjustment for age, sex, smoking, blood glucose, serum total cholesterol, body mass index, antihypertensive treatment, and history of cardiovascular events (From Mancia et al. [21], with permission)

7.4 Identification of Higher and Lower Cardiovascular Risk Subjects with White Coat Hypertension

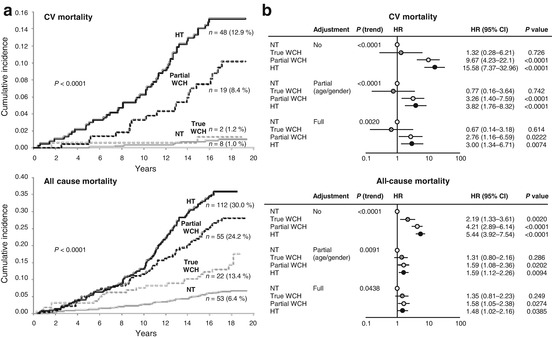

The different results of studies on the prognostic value of white coat hypertension justify the hypothesis that this condition may have a high prognostic heterogeneity. Namely, that depending on its more or less frequent coexistence with metabolic risk factors, subclinical organ damage, and other features involved in cardiovascular risk, its relationship with an increased incidence of morbid or fatal cerebrovascular or cardiac events may turn out to vary within a range that has at one extreme a similarity with true normotension and at another extreme a similarity with true hypertension. Analysis of the PAMELA data has detected two possibilities to differentiate the cardiovascular risk level within the white coat hypertension category. One, because in all individuals of the PAMELA study measurements included both ambulatory and home blood pressure, white coat hypertensives were subdivided into those in whom both out-of-office blood pressure values were normal and those in whom one blood pressure was normal, while the other was elevated or vice versa [21]. As shown in Fig. 7.8, the incidence of cardiovascular events was markedly greater in the latter as compared to the former group in which the risk was only slightly and nonsignificantly increased compared to that seen in true normotensive subjects. Thus, the information provided by ambulatory and home blood pressure is by no means redundant. Indeed, the combined use of these two diagnostic approaches may serve the important purpose to identify white coat hypertensives in whom a substantial increase of cardiovascular risk may justify not only a close follow-up but perhaps also initiation of antihypertensive drug treatment.

Fig. 7.8

(a) Cumulative incidence and (b) hazard ratio (HR) for CV and all-cause mortality in NTs, WCHs, and HTs of PAMELA study over a long follow-up. NTs and true HTs were defined as in Fig. 7.7. WCH was defined as true or partial according to whether, respectively, (1) both ambulatory and home blood pressures were normal and (2) or only one of these blood pressures was normal. For other explanations and symbols, see Fig. 7.7 (From Mancia et al. [21], with permission)

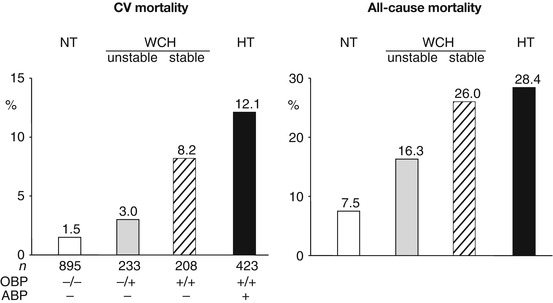

The second possibility is offered by repetition of office blood pressure measurements. Because in the PAMELA study office blood pressure was measured three times at a visit performed before and three times at a visit performed after completion of 24 h blood pressure monitoring , white coat hypertensive subjects could be subdivided into four groups according to whether this condition was found twice or in only one of the office visits. As shown in Fig. 7.9, patients with “stable” white coat hypertension had an incidence of cardiovascular fatal events that was greater than that of individuals in whom the office BP elevation was seen one time only. This was the case also for all-cause mortality which in subjects with stable white coat hypertension was only slightly less than that of patients with true hypertension.