Fig. 1.1

Accumulation of immature myeloid cells (iMCs) around disseminated cancer cells in the liver. (a) A metastatic focus in the liver stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (left). Serial sections were immunostained for pan-cytokeratin (CK), CD45, and CD11b. L adjacent normal liver, T metastasizing tumor. Scale bars 100 μm. (b) Liver metastasis foci dissected at days 3, 7, 14, and 21 post-injection. Open arrowheads indicate disseminated tumor cells, filled arrowheads indicate a cluster of the iMCs, and asterisks indicate a necrotic area. L adjacent normal liver, T tumor glands. Insets show a representative carcinoma cyst. Scale bars 100 μm (Reproduced with permission from Kitamura et al. 2010, with minor modification)

1.2.2 Mouse CRC Cells Secrete CC-Chemokine Receptor 1 (CCR1) Ligand CCL9 and Recruit CCR1+ iMCs to the Liver

We next investigated CC-chemokine receptor 1 (CCR1) expression, another important characteristic of the iMCs. Most iMCs at the metastatic foci expressed CCR1, whereas the cancer epithelium did not (data not shown). Because specific ligands activate CCR1 (Balkwill 2004) and recruit the iMCs (12), we looked for such ligands that were expressed by the CRC cells. Among them, CMT93 cells expressed only Ccl9 mRNA, but not others (data not shown). Consistently, cultured CMT93 cells secreted the CCR1 ligand CCL9 protein (25 ± 3 pg/105 cells) at a similar level to that of intestinal cancer cells from Apc/Smad4 polyps. Immunostaining data also confirmed that metastasized CMT93 cells expressed CCL9 but the surrounding stromal cells did not (data not shown).

To assess the importance of CCL9 in iMC accumulation in the liver, we prepared CMT93 derivatives that contained short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against Ccl9 or control scramble RNA. As expected, almost all metastatic foci formed by control cells accumulated iMCs markedly. In contrast, such accumulations were not observed in the majority of foci by the CCL9-reduced CMT93 cells (data not shown). Collectively, these results suggest that activation of CCR1 by cancer-secreted CCL9 is critical for the iMCs to accumulate at the metastatic foci. As an exception, we found several small metastatic lesions where numerous iMCs accumulated despite the lack of CCR1 (data not shown), suggesting a rare alternative mechanism that can recruit iMCs independent of CCR1.

1.2.3 Inactivation of the Mouse CCL9–CCR1 Signaling Blocks Metastatic Expansion of CRC in the Liver, and Prolongs Host Survival

Because the iMCs helped invasion of primary tumors in the intestines (Kitamura et al. 2007), we hypothesized that accumulation of the iMCs could also promote the metastatic expansion of disseminated colon cancer in the liver. We therefore injected luciferase-expressing CMT93 cells into nu/nu mice, which enabled monitoring of the liver tumors by bioluminescence over time. In mice injected with the parental CMT93 or CMT93-scramble cells, the intensity of bioluminescence began to increase at day 7 post-injection and increased exponentially thereafter (Fig. 1.2a, b). In contrast, such an increase in luminescence was markedly suppressed in mice injected with CMT93-shCcl9#1 cells, although they showed essentially the same levels of luminescence as control groups up to day 3. Another shRNA construct (shCcl9#2) showed a similar effect, though at a weaker level than that of shCcl9#1 (Fig. 1.2b). Of note, all CMT93 derivatives showed essentially the same luciferase activity and proliferation rate in culture. We then injected luciferase-expressing CMT93 cells into the wild-type and Ccr1 −/− mice. Although all wild-type mice showed marked increases in the luminescence level at day 14 post-injection, such an increase was not observed in 70 % (7/10) of Ccr1 −/− mice (Fig. 1.2c). In these hosts, we did not find any macroscopic foci on liver surfaces (Fig. 1.2d). These results indicate that accumulation of the iMCs via the CCL9–CCR1 axis plays a major role in the expansion of liver metastasis foci. Consistently, inactivation of the CCL9–CCR1 signaling prolonged the survival by blocking early metastatic expansion (Fig. 1.2e, f).

Fig. 1.2

Blockade of CC chemokine receptor 1 (CCR1) ligand 9 (CCL9)–CCR1 signaling suppresses expansion of metastatic lesions and prolongs host survival. (a) Representative in vivo bioluminescence images of mice injected with luciferase-expressing CMT93 cells that contained scramble RNA (top) or short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against Ccl9 (bottom). The colored scale bar represents intensity of bioluminescence in photons/s. (b) Quantification of metastatic lesions by bioluminescence (photon counts) from luciferase-expressing CMT93 cells [Parental (Prnt)], or their derivatives that contained scramble RNA [Scramble (Scr)] or shRNA against Ccl9 (shCcl9#1 or shCcl9#2). Results are given as the means ± standard deviation. *P < 0.02 and † P < 0.02 compared with Parental and Scramble, respectively (n = 8–11 mice in each group). (c) Quantification of metastatic lesions by bioluminescence from luciferase-expressing CMT93 cells injected into wild-type and Ccr1 −/− mice. Each circle represents an individual mouse. Horizontal lines show the means of the respective groups. *P < 0.01. (d) Representative macroscopic views of the liver dissected from wild-type and Ccr1 −/− mice injected with CMT93 cells. Scale bars 10 mm. (e) Kaplan-Meier plot showing survival of wild-type hosts injected with control CMT93 cells (Prnt and Scr) or those containing shRNA constructs against Ccl9 (shCcl9#1 or shCcl9#2). *P < 0.01 and † P < 0.02 compared with Prnt and Scr, respectively (n = 5–10 mice in each group). (f) Survival rates of wild-type and Ccr1 −/− mice injected with parental CMT93 cells. *P = 0.0001 (n = 12–13 mice in each group) (Reproduced with permission from Kitamura et al. 2010)

1.2.4 Lack of Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP) 2 or MMP9 in the Host Mouse Suppresses Expansion of Metastatic Liver Lesions

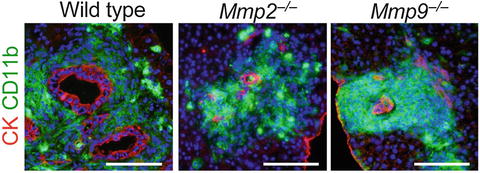

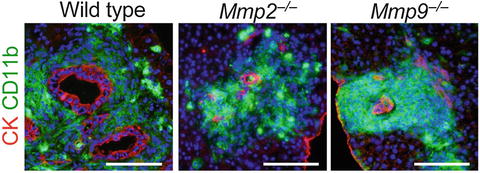

For metastatic expansion in the liver, disseminated cancer cells need to invade the liver parenchyma. We therefore hypothesized that the iMCs promote intrahepatic invasion of disseminated cancer through secretion of proteases. To identify such enzymes, we compared mRNA levels in the metastatic foci between the wild-type and Ccr1 −/− mice by microarray and RT-PCR. The results showed more than two-fold increases in the levels of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) genes Mmp2, Mmp7, Mmp9, and Mmp13 in the iMC-associated foci in wild-type mice (data not shown). In such lesions, MMP2 and MMP9 were expressed in the stromal iMCs, but not in the cancer epithelium (data not shown), whereas MMP7 and MMP13 were found primarily in the epithelium (data not shown). Consistently, MMP2 and MMP9 were absent around the liver foci in Ccr1 −/− mice where the iMCs were missing, although MMP7 and MMP13 were present (data not shown). We then injected luciferase-expressing CMT93 cells into Mmp2 −/− mice, and found significant reduction in the liver luminescence at day 14 compared with those in Mmp2 +/+ littermates (data not shown). Likewise, the luciferase luminescence was much lower in Mmp9 −/− mice than in Mmp9 +/+ littermates, whereas such a reduction was not observed in Mmp7 −/− mice (data not shown). Notably, almost all metastatic foci in the Mmp2 −/− and Mmp9 −/− mice consisted of smaller cancer glands than those in wild-type mice, although they were associated with numerous iMCs (Fig. 1.3). These results suggest that both MMP2 and MMP9 are critical for the iMCs to promote metastatic expansion of CRC cells, but not to accumulate in the liver.

Fig. 1.3

Lack of matrix metalloproteinases MMP2 or MMP9 inhibits expansion of metastatic liver lesions. Liver metastasis foci in wild-type, Mmp2 −/−, and Mmp9 −/− mice injected with CMT93 cells. Scale bars 100 μm (Reproduced with permission from Kitamura et al. 2010)

1.2.5 Some Human CRC Cells Express CCR1 Ligand CCL15

To test whether human CRC cells could recruit iMCs, we injected four cell lines into the spleen of nu/nu mice, and found that HT29 cells were associated with the iMCs in the liver, whereas HCT116, DLD-1, or SW620 cells were not (data not shown). Based on the structural similarity, human orthologs of mouse CCL9 have been suspected to be CCL15 and/or CCL23 (14–16). Thus, we determined the levels of these chemokines in 11 human colon cancer cell lines, and found that six of them, including HT29, expressed CCL15 mRNA and protein at high levels, but none expressed CCL23 (data not shown). We could not detect mRNAs for any other CCR1 ligands (CCL3, 4, 5, 7, 14, or 16; data not shown). We further verified by western blotting that 28 % (13/47) of human colon cancer specimens expressed CCL15 protein (Fig. 1.4a). An immunostaining analysis also showed that 29 % (12/41) of primary tumors and 29 % (12/41; a separate combination) of liver metastases expressed CCL15 in the cancer epithelium (Fig. 1.4b). These results demonstrate that a subset of human CRC cases secretes CCL15, and suggest that it may recruit CCR1+ human iMCs.