11

Building a Successful Tumor Ablation Practice

A successful tumor ablation practice is a crucial and rewarding addition to the modern interventional practice. Whether tumor ablation becomes a component of a broad interventional oncology practice with chemoembolization and yttrium-90 radioembolization, or alone as the first foray into cancer therapy, tumor ablation has become a necessary addition. Interdisciplinary turf battles, intrasubspecialty competition, and broad health care expansions into new regional cancer centers have placed additional demands on traditional radiology groups to offer new interventional oncology treatments. Percutaneous tumor ablation may be the most appealing new treatment for the traditional interventional radiologist. A new tumor ablation practice can potentially be launched from radiology practices that perform diagnostic tumor biopsy, a frequent and common procedure. This includes existing cancer patient referrals from oncologists and available technical skills for image-guided procedures.

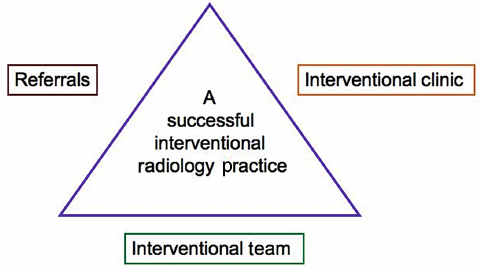

Central to building a tumor ablation practice is the need to contemplate a change of focus from a procedure-centered practice to a practice that incorporates longitudinal patient care. This new paradigm should center on patient longitudinal care with initial consultation, intervention, and follow-up.1–3 These new responsibilities pose new administrative and clinical challenges. No matter which practice strategies you choose, three fundamental areas need to be addressed: referrals, the interventional radiology (IR) clinic,1,4,5 and the IR clinical team (Fig. 11.1). Setting goals within each of these areas will provide a solid foundation on which the practice can grow. This chapter provides several strategies for overcoming obstacles and building a successful tumor ablation practice.

♦ Preparing the Groundwork and Generating Support

Educating your radiology partners and support staff and creating the right environment for the initiation of an ablation practice is an important first step. Most importantly, support from your diagnostic radiology partners is crucial in generating the momentum for establishing the new service, funding the start-up costs, and finding the time to build the practice. Your radiologist colleagues, who make the initial imaging cancer diagnosis, need to be informed about the indications for potential ablation patients so that both the cancer diagnosis and the ablation potential can be mentioned when they communicate the diagnostic findings with the referring physician. The radiology administrative staff needs to be educated about the new procedures being offered, and about how to manage new scheduling demands for the clinic, the procedures, and for follow-up. Hospital credentialing requirements for radiologists need to be determined, and a strategy needs to be developed to obtain the necessary training and documentation, whether by means of industry-sponsored proctorships/ workshops, or conferences at professional meetings.

Fig. 11.1 The three cornerstones of a successful ablation practice.

There are factors that may help persuade your partners that the expenses of starting tumor ablation can be warranted. The financial benefits of adding tumor ablation to any practice can be substantial including income from doing the procedures, from clinic appointments (evaluation and management income) as well as from follow-up imaging (computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography). Other intangible benefits include enhancement of professional relationships (with oncologists and others), as well as enhancement of the practice’s standing within the hospital and the community at large.

♦ Building a Referral Base

Within the Hospital

Building a tumor ablation practice needs referring physicians first to be aware of tumor ablation and thereafter to actually refer their patients. This requires the oncologist to be familiar with ablation’s potential benefits either as a result of prior formal training or, for the unaware, through new educational and marketing initiatives. Changing perception and awareness can be challenging, especially for the latter group of physicians, who may initially be skeptical. It is easiest to start within one’s affiliated hospital system, with one’s established relationships built around the cancer-related procedures that are already being performed in your department, including tunneled central venous catheterization for chemotherapy, percutaneous gastrostomy procedures, and biopsies of suspicious masses. Having an existing group of oncologists that refer patients for other cancer-related procedures to your practice is a valuable advantage and one that should be fostered by making office visits to the oncologists to discuss the potential benefits of ablation.

Tumor Board

Participation in a multidisciplinary tumor board is the most important aspect of building an ablation practice. Physicians who perform cancer-related procedures must actively participate in the forum where modern cancer treatment is formulated. As a diagnostician and potential therapist, the interventional radiologist is uniquely poised to offer both scan interpretation as well as therapy options. Frequently, the radiologist’s role in interpreting scans is done by one of your diagnostic colleagues and requires your additional presence at the tumor board. Initially, passive attendance at tumor board may be helpful in becoming familiar with the oncology experts in your hospital and local oncology practice politics, learning cancer terminology, and enhancing understanding of cancer therapy concepts. In addition, assessing the general work flow of the local tumor board is helpful, as each board has its own politics and tolerance of new therapies. Thus, it may be prudent to act as an observer rather than aggressively suggesting tumor ablation at every meeting. Potential tumor ablation referrals may be difficult to generate if the suggestion is met with resistance initially, and it may take time, patience, and resilience to overcome this skepticism. Some practitioners have invited speakers from major universities or other large-volume ablation practices to speak at the tumor board to introduce the role of ablation in cancer therapy. Industry spokesmen frequently can assist in this regard and facilitate the ablation expert’s inclusion for continuing medical education for the board members. The speaker can address some of the initial concerns, defend the role of tumor ablation, as well as demonstrate the advantages already achieved elsewhere by reviewing previously published clinical data and papers on tumor ablation.

Four other possible strategies to improve one’s initial success in starting a successful ablation practice are:

- Offering to treat patients with limited or no therapy options

- Acquiring a general understanding of the basic oncology scientific literature

- Combination treatment with ablation

- Sharing procedures

Treating Patients with Limited Options

Introducing a new cancer treatment option can often draw immediate opposition (turf wars). The three main specialties that deliver cancer therapy can all potentially feel apprehensive about percutaneous tumor ablation as a new alternative: surgical oncology (for potential resectable tumors), radiation oncology (for nonsurgical patients), and medical oncology (for chemotherapy patients). A very effective initial strategy is to focus on patients who are outside the range of these three specialties—that is, patients with the least, or even no, therapy options.5 A nonthreatening approach is to suggest ablation for only the following types of patients: nonoperative candidates, those who are not radiation candidates because they have reached the maximum lifetime radiation doses, or those who have progressed through several lines of chemotherapy. Ablation can also be used as symptom control palliation. However, there must be a potential benefit; it is crucial to select the initial ablation patients carefully, as it is imperative to be at least somewhat successful in the initial stages, no matter how modest the proposed intended goals (e.g., tumor progression stabilization). Most oncologists find it frustrating to reach the point for terminal cancer patients when all standard therapies fail, so when ablation practitioners offer a new option for these patients, it will be well received if you can improve patient outcomes or quality of life with tumor ablation for their initial referrals.

Thus, the initial candidates for a new ablation practice can include the following clinical scenarios:

- Patients with intractable bone pain from mass-forming bone metastatic lesions who have failed radiation or reached radiation maximums. These patients are difficult to treat, as they have a great amount of morbidity. Ablation not only yields a tumoricidal effect that is visible and reproducible on scans, but also, more importantly, may improve the well-being of their patients with clinical significant pain improvement, which may be the springboard for more referrals.

- Patients who have failed chemotherapy. Patients with disease that has progressed through three lines of chemotherapy can be treated with debulking/cytoreduction ablations for disease control.

- Patients with lung malignancies who have reached the radiation maximum (e.g., lung cancers in chronic obstructive airway diseases).

- Patients with tumors that are not chemotherapy or radiation sensitive (e.g., some types of sarcomas).

- Patients whose cancers are resectable but who have medical comorbidities (e.g., cardiovascular disease in renal cell carcinoma), rendering them nonoperable.

- Patients who are symptomatic; lung radiofrequency ablation (RFA) can be used for hemoptysis that was caused by lung cancers (cauterization effect of RFA).

Know the Cancer Literature

Most consensus cancer treatment plans (standards of care) are formulated on a national level by preeminent multidisciplinary panels, and familiarity with these general guidelines is important. Cancer physicians are generally accustomed to using evidence-based medicine to make methodical treatment decisions, and understanding the applications of tumor ablation is crucial for its introduction. As a simple example, suggesting that a small (2-cm) liver hepatocellular carcinoma be ablated would be very naive if resection or referral to a transplant center was not discussed first, even if the patient was a candidate for liver RFA. The prospect of acquiring this type of new knowledge may be daunting for senior interventional radiologists, having never been taught it in their former training. But gaining sufficient knowledge and comfort in the basic cancer therapy concepts and terminology in the main organ systems where ablation is applied—liver, lung, kidney, and bone—is all that is needed. Oncology textbooks (see Chapter 9), review articles, and the Internet are good sources of information.

A recommended Web site is the National Cancer Comprehensive Network at www.nccn.org.6 This site is widely recognized and used as a reference for standards of clinical policy for both cancer specialists as well as insurance companies (as standards of care). Summaries of each organ system and cancer type as well as treatment algorithms are included. This site also includes some basic information about expected patient survival outcomes and cancer natural histories. Treating with RFA a single liver colorectal cancer metastasis that has progressed through two lines of standard chemotherapy is much more appropriate than suggesting liver RFA for pancreatic liver metastases, even if it is technically possible from an imaging point of view. Clinically naïve recommendations would lead oncologists to mistrust your understanding of clinical cancer practice and would hinder introducing tumor ablation in your hospital. In addition, basic familiarity with cancer terminology would facilitate documentation and communication. An example of this type of nonradiologic clinical terminology is patient Performance Status (PS). There are several standardized scoring systems that score a patient’s overall fitness for treatment eligibility, such as the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale (see Table 5.2 in Chapter 5), that enable you to communicate with the oncologist in a standardized fashion and will also bring conformity to your clinical notes.6 Moreover, scoring patients in terms of performance status is also very helpful in identifying ablation candidates. This is important in the initial stages of the ablation practice when focusing on patients with good functional reserves (high performance status) so that side effects and complications can be avoided, and thus not sabotaging your practice from the start. Declining to treat certain patients, such as borderline cases, can be just as important for practice building. In the tumor board setting, it demonstrates a clinical acumen that will generate respect and build credibility in the long run.

Combination Therapy

Another way to mitigate turf wars is to suggest combination therapy with thermal ablation. First establish credibility and technical success with follow-up scans showing sustained tumor destruction. Some medical oncologists have gone on to embrace thermal ablation as another cancer weapon, even to consider it as synergistic with chemotherapy. Conceptually, it is similar to chemoradiation but without radiation field side effects and can be attractive to those who have exceeded radiation doses. Combination therapy is common in cancer treatment (e.g., chemoradiation), and encouraging oncologists to view ablation as another palliative therapy in their arsenal can be fostered if it can be demonstrated that ablation enables systemic chemotherapy to continue. Ablation can treat local disease and attain tumor control, while chemotherapy controls the systemic component of all stage 4 disseminated disease. This rationale would apply in a patient with metastatic colorectal cancer who has been treated with systemic chemotherapy by medical oncology, resulting in most of the extrahepatic disease being controlled, except for one or two lesions in the liver. Normally, if the liver lesions progress, this would be regarded as overall failure of this line of chemotherapy. By using liver RFA, the lesions can be ablated during a normal scheduled break from chemotherapy (“chemo holiday”), and thereby not delaying routine chemotherapy intervals (the medical oncologists’ turf) and extending drug options. Maintaining therapy options is critical to the medical oncologist. At a basic level, medical cancer treatments consist of trials of therapy options until they all fail, ultimately leading to terminal hospice care. Thus, medical oncology should be the main target of your practice-building efforts. Medical oncologists are the true “gatekeepers” of cancer patients, as they control medical management. If you can demonstrate that ablation will not deprive them of patients but rather provide them with another option besides radiation, medical oncology can be your biggest potential referral source.

Finding common ground with radiation oncology can be more elusive. Ablation and radiation can be direct competitors. A similar synergistic approach can be tried to overcome turf anxiety by working together. An example would be to combine with radiation for the treatment of large lung masses; ablation could potentially treat the central hypoxic parts of the tumor (notoriously difficult to treat with radiation), and radiation would target the exterior of the tumor (typically difficult for ablation to treat if >5 to 7 cm).

Surgical Downstaging

Another form of combination therapy would be utilizing tumor ablation for surgical downstaging for a patient with previously unresectable disease, such as a large primary liver cancer that is successfully ablated and reduced in size to the point that allows for resection or transplantation. This application of ablation could be regarded as a form of neoadjuvant therapy (treatment before surgery). Surgeons embrace percutaneous tumor ablation more readily because many open surgical ablations are done in the operating room by surgeons, and thus the technology is familiar to them. As long as your intention is to treat nonsurgical patients, surgical oncologists will be supportive and can be an ally in the tumor board setting. Another step that is conducive to building an ablation practice is referring patients back to surgery if they have responded so well to ablation that they become resectable candidates. Or you can ask a radiation oncologist to try combination therapy for larger masses that are beyond the ablation margins. This promotes a “give and take” relationship with your referring doctors and will give you tremendous credibility as a member of the cancer team who is trying to enhance patient clinical outcomes.

Shared Procedures/Revenue

A strategy that can be helpful is to consider shared revenue. In some states, coding allows for a “surgeon in attendance fee,” and allows some profit sharing. Some operators describe starting a renal tumor ablation practice by asking urologists to treat renal cancer patients who are not surgical candidates (usually due to medical comorbidities) and sharing the revenue. In addition, the feasibility of revenue sharing is enhanced for radiology because of biopsy, scan, and follow-up scan fees. This arrangement may be viewed by some as suboptimal; however, it does allow some surgeons to maintain some patient care control and increases the performance of radiology procedures that otherwise would not have been done. More importantly, it helps a group of patients who have few options.

Outside Your Hospital System

A successful ablation practice will also be able to attract patients from outside the hospital system once referrals have been maximized within the hospital. By researching your regional physicians by specialty, you can market your practice to groups that do not typically refer diagnostic work to you, but may refer patients specifically for tumor ablation if this expertise is not readily available in the region. Some suggestions to increase out-of-hospital referrals include the following:

- Web site. This can serve to introduce referring physicians and staff, and educate future patients about ablation procedures. Patients frequently hear about ablation from the mass media or online support groups, and either self-refer or insist on being screened.

- Presentations/lectures. Participate in grand rounds and “meet-and-greet’ lunches to present your work to different practices outside your hospital and to smaller community hospitals. Remember to remain objective and be sure you know the literature. One single physician referring a steady flow of ablation patients can be all that you need, and it allows you to build credibility and gives you a platform on which to showcase the benefits of ablation.

- Marketing. There are many different types of media that can increase the referrals and disseminate the information in a controlled way. Consult with your hospital’s public relations department, which seeks to promote new procedures in the hospital, and may be willing to fund local advertising or to reach out to the local media. Bringing an outside speaker through your hospital’s continuing medical education office may generate both educational and marketing benefit. Local cancer support groups are frequently interested in speakers on new therapies, as are general groups such as the Rotary and the Lions. Place bulletin boards in your practice’s waiting areas, on which you can post abstracts from scientific publications about ablations and other interventional treatments. However, the posted material should be carefully considered and sensitively displayed, as referring physicians may be offended by unsolicited advice directed toward their patients who were referred for other diagnostic reasons.

♦ Clinical Service Infrastructure: Clinical Team and Outpatient Clinic

As in most medical specialties, the outpatient clinic should become the cornerstone of an ablation practice.1 This environment is crucial in helping establish, maintain, and develop the physician–patient relationship. Nurturing this relationship will help interventionalists improve the clinical care for their patients. In addition, it will demonstrate to your referring physicians your dedication to transitioning from a procedure to a longitudinal centered approach.

Although establishing a clinic space may be a big step, it is necessary in order for the practice to succeed. If no dedicated space is available, try to share clinical space within the hospital’s clinic area to decrease costs. Successful ablation practices ideally should encompass some form of preprocedural patient assessment (consultation) and clinic follow-up. Only in this type of setting can we give a true clinical consultation, where a patient can be fully assessed and a clinic note written. This note generates the basis for insurance documentation, detailing the rationale and medicolegal protection for our decisions (risks and benefits, including prognosis). This is critical if interventional radiology is to be considered a true provider of cancer treatment. However, with the ever-increasing demands placed on interventional radiologists (outpatient clinic, inpatient rounds, follow-up clinic, attendance at a multidisciplinary tumor board, calling physicians and patients), it is both necessary and ultimately efficient to have a team to assist in the care of ablation patients.

Physician Extenders

Central to this team is the addition of a physician extender. Although the team members will differ between an academic and a community hospital practice, it is important to construct a team that will match your strategic plan. Team members can include physician extenders, nurses, radiologic technologists, fellows, radiology residents, and medical students, depending on your type of practice.

The different types of physician extenders are physician assistants (PAs), nurse practitioners (NPs), nurse coordinators, and radiology practitioner assistants (RPAs). PAs are nonphysician clinicians licensed to practice medicine with a physician’s supervision, whereas NPs have an advanced primary care education. The major difference between NPs and PAs is that NPs can bill without physician supervision. RPAs are radiology technologists with additional radiology training that expands their duties to include patient assessments and patient management. PAs and NPs are the most common physician extenders in interventional radiology. Although the cost of hiring physician extenders may initially seem prohibitive, the cost is balanced by the income that they generate from clinic encounters with patients, from E&M coding revenue, or from basic interventional procedures such as central line placements. A small-business plan (using real collection rates) can be used to rationalize the startup costs. Approaching hospital administrators is another attractive strategy if you can demonstrate how much benefit a tumor ablation practice can bring to the hospital, both in direct and indirect benefits, particularly if you need to admit patients overnight after ablations. Typically, reimbursement is higher for ablations performed on inpatients. Hospital-funded physician extenders are very common in other specialties, and many IR groups around the country have had success funding their clinical team by hospital administration support.

Frequently, a single physician extender with a background in clinical medicine (especially in oncology) is sufficient until the practice expands. It is not unusual nowadays to hear of community IR groups with up to five or six physician extenders. They become a crucial part of the service and enhance the interventional radiologist’s ability to function maximally and effectively. These benefits outweigh the increased salary and recruitments costs needed to attract physician extenders (Table 11.1). The physician extender provides the information that forms the basis of the clinical note, including the history and physical examination, and collects the prior records and scans, allowing the interven-tionalist to perform a brief, focused encounter in the clinic, discussing management options and answering patient questions. Thereafter, the physician extender coordinates laboratory testing, scheduling, and insurance authorization with the billing personnel.

| Disadvantages | Advantages |

|---|---|

|

|

Admission Services

Although not a necessity, the ability to admit patients under your own service after ablations is extremely valuable. Your ability to take care of standard postprocedural issues is reassuring to patients as well as referring physicians, and generates professional credibility in the hospital. In addition, it raises your value to the hospital administrators as a primary source of revenue and patients, and in turn strengths your requests for physician extender salary support. No interventionalist wants to become a primary care physician, and appropriate consultation with other specialties with more complex patients, or admitting them to higher care under intensive care specialists, is appropriate. If available, hospitalists are excellent resources to use for overnight admissions should you not have admitting privileges or have a medically complex patient.

Practice building in a budding tumor ablation program is crucial to its success, both to its financial viability and to its sustainability. Utilizing key strategies can improve the obstacles that early tumor programs face by creating sustainable ablation volume to support technical expertise, operator comfort, and, most importantly, patient clinical outcomes.

- Get referrals through the following steps:

- Attend tumor board meetings.

- Treat patients who have limited treatment options.

- Ablation can lead to surgical downstaging.

- Ablation can be used as combination therapy.

- Attend tumor board meetings.

- Treat patient with limited options:

- Unresectable patients

- Patients who have failed multiple lines of chemotherapy

- Patients who have reached the radiation therapy maximum

- Patients with multiple medical comorbidities

- Patients who are symptomatic from tumor invasion/mass effect

- Patients who have intractable bone pain from metastases

- Patients who have chemo- and radiation-resistant tumors

- Unresectable patients

- Build credibility for yourself and the service:

- Bring in an outside expert for a tumor board presentation.

- Know the basic oncology data.

- Familiarize yourself with oncology terminology.

- Decline the treatment of hopeless cases.

- Refer new cases back to supporters.

- Avoid patients with complications and other risky cases.

- Bring in an outside expert for a tumor board presentation.