Fig. 8.1

Office systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic (D) BP, and heart rate (HR) values at baseline and during antihypertensive drug treatment (1–48 months) in subjects with white coat hypertension (WCH) (n = 251) and sustained hypertension (SH) (n = 1,670). Data are shown as means ± standard deviation. Treatment consisted of the initial administration of lacidipine or atenolol followed if needed by the addition of other drugs

Fig. 8.2

Office SBP, DBP, and HR changes induced by treatment in subjects with WCH and SH. Data (means ± standard deviation) are shown separately for patients treated with lacidipine and atenolol. Symbols as in Fig. 8.1

The conclusion that in white coat hypertension office blood pressure can be effectively lowered by antihypertensive drugs independently of its type and mechanism of action is in contrast with a phenomenon that has come to the attention of clinicians and investigators years ago. That is, that in a notable fraction of patients with resistant hypertension, i.e., those in whom three or more antihypertensive drugs administered at adequate doses do not show a satisfactory therapeutic effect, ambulatory or home blood pressure is found to be within their normal limits (Fig. 8.3), with a cardiovascular risk that is definitively less pronounced than that of resistant hypertensive individuals in whom both in and out-of-office blood pressure is elevated [23–26]. These patients are therefore white coat hypertensives in whom drug treatment does not lower office blood pressure values, no matter how intensive and protracted. As far as the response of office blood pressure to drug treatment is concerned, it thus seems that we have to consider a population of white coat hypertensive individuals who respond to antihypertensive treatment but also a number of patients in whom the elevated office blood pressure values remain persistently high, despite use of multiple medicaments and repeated changes of treatment strategies [13]. The clinical characteristics of the two groups have never been compared, and it is unknown whether the factors responsible for the lower ambulatory or home versus the office blood pressure values differ in the two groups.

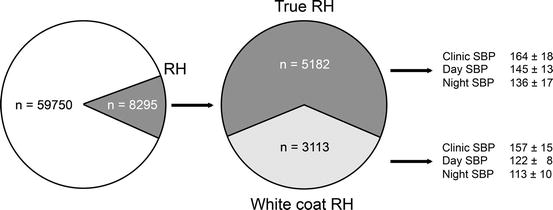

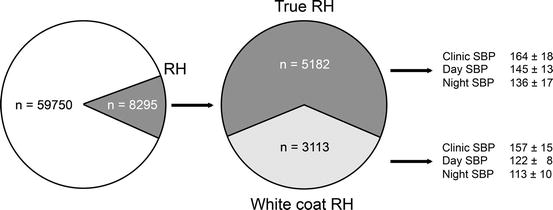

Fig. 8.3

Prevalence of true and white coat resistant hypertension (RH) based on office and ambulatory blood pressure values. True resistant hypertension was defined by office and ambulatory blood pressure elevations, whereas pseudohypertension was defined as elevation in only office blood pressure. Data from about 60,000 patients followed in the clinical practice setting. RH was found in 13.9 % of the hypertensive population. In 37.5 % of them, ambulatory blood pressure was normal (From de la Sierra et al. [26], with permission)

8.3 Antihypertensive Drugs and Out-of-Office Blood Pressure

Several years ago the concept has been expressed that in white coat hypertension, drug treatment has no effect on ambulatory blood pressure [1]. This was based on a report of Pickering et al. [14] that, although effectively reducing office blood pressure, doxazosin did not have any lowering effect on ambulatory blood pressure values in white coat hypertension. It was also based on studies in which white coat hypertensives were given calcium channel blockers , ACE inhibitors, or other drugs which all caused reductions in office blood pressure without, however, any substantial reduction of day or 24-h blood pressure values [15–19]. However, other observations have turned out not to be entirely in line with the conclusion that in white coat hypertension ambulatory blood pressure is unaffected by treatment. Two studies have reported that the ambulatory blood pressure values of white coat hypertensive individuals were reduced by treatments based on ACE inhibitors , although not by the ones based on calcium channel blockers [19, 20]. Another study has reported a marked and sustained (1 year) reduction of both office and ambulatory blood pressure in black hypertensives treated with long-acting nifedipine [27]. Finally, a recent analysis of the data obtained by the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) on hypertensive patients aged ≥ 80 years has shown that an antihypertensive treatment based on indapamide with the frequent addition of the ACE inhibitor perindopril lowered to a notable degree not only office but also ambulatory blood pressure both in subjects with sustained hypertension and in those defined as white coat hypertensives based on ambulatory blood pressure normality [28].

Detailed evidence on the effect of antihypertensive drug treatment on ambulatory blood pressure in sustained and white coat hypertensive subjects has been provided by a post hoc analysis of the data obtained in the ELSA trial [29] because in this trial all recruited patients underwent an ambulatory blood pressure monitoring at baseline and at yearly intervals over a 4-year treatment period with either lacidipine or atenolol [22]. As shown in Fig. 8.4, treatment significantly lowered 24-h mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure in sustained hypertension with no loss of the blood pressure-lowering effect throughout the study duration. In striking contrast, ambulatory blood pressure did not exhibit any reduction in white coat hypertensive patients. On the contrary, from the first to the fourth year of treatment, there was a slight but significant progressive increase in the 24-hour (h) mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure values, which at the end of the treatment period were 2.8 and 0.59 mmHg greater than before treatment. This provides strong support to the conclusion that antihypertensive treatment is by and large not capable of lowering ambulatory blood pressure in white coat hypertension. It also provides evidence that the opposite is indeed the case, i.e., that despite drug treatment, there is a tendency for daily life blood pressure values to increase over years.

Fig. 8.4

Twenty-four-hour mean SBP and DBP in white coat and sustained hypertension before and during treatment with lacidipine or atenolol. Data are shown as absolute values (top panels) and changes from baseline (bottom panels). Changes were calculated by averaging the data provided by the yearly ambulatory BP monitorings (n = 4). Symbols as in preceding figures

Why in white coat hypertension ambulatory blood pressure is unaffected by antihypertensive treatment is not clear. The most obvious possibility is that the “law of the initial value” makes the blood pressure reduction achievable by antihypertensive drugs proportionally less pronounced as the baseline blood pressure becomes progressively less, with little no effect when it is normal or low. Indeed, this has been found to occur for ambulatory blood pressure [30], the absence of any treatment-induced fall being predicted at values around 125 mmHg systolic and 80 mmHg diastolic [31]. However, in studies on sustained hypertensives, treatment has been found to be able to lower ambulatory blood pressure to values less than 125/80 mmHg (Fig. 8.5) [32, 33]. Furthermore, when in the ELSA study white coat hypertensive patients were divided into three groups according to their baseline ambulatory blood pressure values, no treatment-induced blood pressure reduction was seen also in patients with the highest values and thus with more room for a treatment-induced fall [34]. Finally, as mentioned above, in white coat hypertensive individuals, antihypertensive treatment appears to be accompanied not just by no blood pressure-lowering effect but by a blood pressure increase. This may be due to the regression to the mean phenomenon, i.e., to the fact that whenever a biological value is low there is a high chance that the following measurement will be higher and vice versa. The possibility also exists, however, that white coat hypertension represents a prehypertensive condition , i.e., that it has a high chance of progressing to sustained hypertension. Verdecchia et al. found year ago that 37 % of 83 white coat hypertensives moved to sustained hypertensives over 2.5 years [35]. This has been confirmed by other studies [36, 37], and a much greater risk of white coat hypertensive individuals to develop sustained hypertension has more recently been provided by a 10-year observation period of the PAMELA population [38].

Fig. 8.5

Relationship between office and 24-hour (h) mean SBP and DBP in the treated hypertensive patients of a mulTicenter study evALuating the Efficacy of Nifedipine GITS–Telmisartan combination in blood pressure control and beyond (TALENT) study. Data refer to a treatment duration of 24 weeks. Treatment consisted of nifedipine GITS and telmisartan. Symbols as in preceding figures (From Mancia et al. [32], with permission)

8.4 Antihypertensive Treatment and White Coat Effect

Studies on antihypertensive drug treatment agree that the lowering effect is greater for office than for ambulatory blood pressure [39], which means that the office-ambulatory blood pressure difference, i.e., the phenomenon known as the “white coat effect” [1], is usually reduced by treatment. With few exceptions [40], this appears to be the case not only in sustained but also in white coat hypertension [1], a condition in which absence of an ambulatory blood pressure-lowering effect of treatment can make the white coat effect attenuation particularly pronounced. This is exemplified in Fig. 8.6, which is again taken from the data obtained in the ELSA trial. Patients with white coat hypertension exhibited a marked office-ambulatory blood pressure difference at baseline, but the difference was markedly less pronounced during treatment, consistently over the 4-year duration of the trial.

Fig. 8.6

Office-ambulatory SBP and DBP differences before and during treatment in the white coat hypertensive patients of the ELSA study. Symbols as in preceding figures

Does the marked reduction of the office-ambulatory blood pressure difference with treatment just reflect a reduction with time of the alerting response and the office blood pressure rise associated with the doctor’s visit? [41]. This is not an easy question to answer because no conclusive evidence exists on the extent to which repetition of the visit attenuates the pressor effect of blood pressure measurements by a doctor [42].It is also uncertain whether the difference between office and ambulatory blood pressure reflects the alerting response to the abovementioned procedure and thus deserves to be termed the “white coat effect,” as commonly done [11]. This has indeed been challenged by a study in which the office-ambulatory blood pressure difference did not exhibit any significant relationship with the white coat effect quantified directly by beat-to-beat blood pressure monitoring before, during, and after the physician’s visit [43]. It is made unlikely also by indirect arguments such as that (1) when directly assessed by beat-to-beat blood pressure monitoring before, during, and after the doctor’s visit the white coat effect exhibits an increase in both blood pressure and heart rate whereas the office-daytime difference is limited to the blood pressure values [11, 41–43]. Furthermore, the office-ambulatory blood pressure difference shows a progressive increase with age , but elderly people are not characterized by a hyperreactivity to environmental stimuli, their alerting response to the physician’s visit being also similar to that of younger people [41]. Finally, the difference between office and ambulatory blood pressure is not only directly related to office blood pressure but also inversely related to ambulatory blood pressure [44], which is not influenced by the alerting response to blood pressure measurements [45].

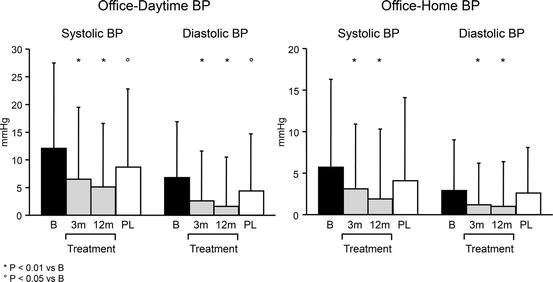

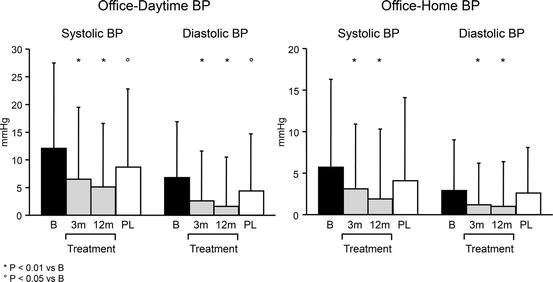

Is the attenuation of the office-ambulatory blood pressure difference with treatment then a treatment-related effect, i.e., the consequence of the ability of antihypertensive drugs to lower office more than ambulatory blood pressure? Although data on white coat hypertension are not available, other observations indicate that this is the case. As shown in Fig. 8.7, compared to the baseline values, the office-ambulatory blood pressure difference was reduced during the visits performed after 3 and 12 months of antihypertensive treatment. There was, however, a recovery during a final month of placebo which proved that the previous attenuation was at least in part due to the differential effect of the drugs employed on in and out-of-office blood pressure [46, 47].

Fig. 8.7

Office-ambulatory SBP and DBP differences in hypertensive patients in whom the difference was measured before treatment after 3 and 12 months of treatment (an ACE inhibitor with the possible addition of a diuretic) and after a final 1-month period of placebo (From Parati et al. [47], with permission)

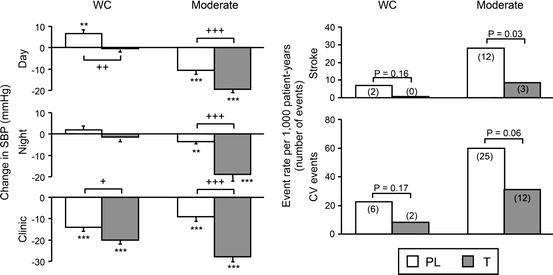

8.5 Antihypertensive Treatment and Cardiovascular Protection

Ultimately, whether treatment is protective on patients with white coat hypertension needs documentation from prospective studies having a proper control group and outcomes of undisputable prognostic significance as endpoints. At present, no such studies have been performed, and the only available evidence is the one obtained from limited number of patients with isolated systolic hypertension recruited from the Systolic Hypertension in Europe trial (SystEur) in whom also ambulatory blood pressure data were collected [48]. Compared to the placebo group, patients with sustained hypertension showed a reduction of office blood pressure, ambulatory blood pressure, and cardiovascular morbid and fatal events. In contrast, white coat hypertensive patients only exhibited an office blood pressure reduction, the nonsignificant fall in ambulatory blood pressure being accompanied by a more modest and nonsignificant reduction of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality as well (Fig. 8.8). However, the study could count on only few events in each group which limited the statistical power to detect between-group differences and made the conclusion that antihypertensive treatment may carry little benefit in individuals in whom blood pressure elevations are limited to office values only tentative. This limitation is shared by the other available evidence, i.e., the one provided by the post hoc analysis of the ELSA trial in which the cumulative 4-year incidence of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality showed a similar slope in white coat and sustained hypertensive patients.