Fig. 9.1

Professor Vaquez measures blood pressure at Hôpital de la Charité in 1910 (From Postel-Vinay [4], by courtesy of John Wiley & Sons)

The first report of a hypertensive patient repeatedly measuring his BP dates back to 1930, when Brown described the daily and monthly rhythm in BP in a man with hypertension who self-measured his BP at home for 3 years [5]. No correlation was made between clinic and home readings, however. The first systematic study of the differences between clinic and home readings was published by Ayman and Goldshine in 1940 [6] in 34 hypertensive patients followed up for an average period of 22 months, during which 2,800 clinic readings and 40,000 home readings were made. Statistics was not popular in medicine at that time, and a statistical analysis of this large amount of BP data was not made. However, the authors reported that the home readings by the patient or a member of the household were systematically lower than the clinic readings and also noticed that both in the clinic and at home initial BP values were the highest and then progressively declined, though remaining higher in the clinic. The phenomenon is explicitly attributed by the authors “to the excitement and tension associated with the visit to the clinic or doctor’s office” [6], i.e. what will be later named “the white coat effect”. The authors did not attempt an explanation for the progressive decline of BP values with repeated measurements also occurring at home where the doctor was absent, but the concept of the emotional context in which BP measurement is taken was further elaborated a few years later, in 1943, by Alam and Smirk [7] when these authors remarked the contrast between “casual” BP to denote the BP measured under uncontrolled conditions in the physician’s office or clinic and the “basal” BP measured in a rigorously defined basal environmental state.

The matter was resumed with the advent of the first effective antihypertensive drugs, the ganglionic blocking agents, “when it became necessary to follow blood pressure more closely than could be accomplished with occasional visits to the office or clinic” [8]. For this reason, use of self-measurement of BP at home became more frequent, and there are three reports in 1954 showing home BP to be lower than clinic BP [8–10]. Smirk [10] remarked that in patients treated with ganglionic blockers “casual blood pressures are taken, but they are of very little use in the control of dosage. Quite high blood pressures may be encountered in outpatients whose blood pressure is satisfactory under home conditions” and referred these findings to some previous study of his group [11] showing that certain emotional stimuli may counteract the hypotensive effects of the ganglionic blocking agents. In a more systematic study of 32 hypertensive patients receiving the ganglionic blocker, pentapyrrolidinium, Freis reported that, while 31 of the 32 cases had a drug-induced systolic BP decrease of at least 30 mmHg when BP was measured at home, 68 % of the patients had a BP reduction lower than 30 mmHg when clinic measurements were used and interpreted the phenomenon as “occasioned by the apprehension associated with the visit to the doctor’s office or clinic” [8]. Additional data on differences between clinic and home BP values were published by Julius and his associates in 1964 [12], and the suggestion was given that home BP measurements could be particularly useful in the decision in favour or against treatment in borderline hypertension [13].

9.2 The Advent of Ambulatory BP Monitoring: New Evidence New Questions

Differences between BP values measured in the office and out of office became more evident and could be investigated in greater detail when methods for automatic continuous or repeated measurements in the ambulatory patient became available. After the introduction of the first non-invasive portable BP recorder developed by Hinman et al. [14], Sokolow et al. [15] in a seminal paper showed that BP values semiautomatically measured during daytime were lower than those measured casually and were more closely associated with severity of hypertensive complications. The authors correctly refrained from interpreting the reasons for the differences between the two types of BP measurements and interpreted the closer correlation of semiautomatically measured BP values with organ damage as a consequence of the larger number of measurements provided by the portable machine.

Introduction of a device for continuous direct (invasive) recording of arterial pressure in unrestricted patients by Littler et al. [16] in 1972 provided further and more detailed information. Littler et al. [17] found that in a small group of treated hypertensive patients, lower BP were measured over 24 h than in the clinic, suggesting that “the difference may have been due to the well-known effect of exercise in augmenting the hypotensive action of drugs” or, alternatively, that the “clinic readings were biased by an unusually sensitive defense reflex” [17], the fault being placed more on the patient’s than the doctor’s shoulders. These observations were expanded a few years later by Floras et al. [18] in a number of untreated “borderline” hypertensive patients. In one group ambulatory mean arterial pressure was 25 mmHg lower than clinic BP, whereas ambulatory and clinic BP values were similar in another group of patients. As patients in whom there was a large difference between clinic and ambulatory BP had no evidence of greater sympathetic activity and of greater blood pressure responses to mental arithmetic and bicycle exercise, the authors concluded that “the reason for the discrepancy between cuff and ambulatory readings is not clear” [18].

If the possibility that the doctor’s involvement in BP measurement may increase BP values dates back to Riva-Rocci himself [2, 3], the demonstration that this really occurs had to wait a specific study by our group in 1983 when Mancia et al. [19] in a number of hypertensive patients with continuous intra-arterial BP recording could demonstrate the transient increase in SBP and DBP initiating when the doctor entered the patient’s room, persisting through the several minutes of the “clinic” measuring procedures and disappearing at the end of the visit (Fig. 9.2). In this paper, and in a following one in which we compared the effect of the doctor’s measurement with the smaller effect of the nurse’s measurement [20], we refrained from using the term “white coat effect” and cautiously used that of “alarm” or “alerting” reaction. Even more cautiously we avoided to suggest that the doctor’s effect on BP was the explanation of the frequent difference between clinic and ambulatory blood pressure.

Fig. 9.2

Original tracing from one subject of blood pressure and heart rate in 15 min when a doctor was at bedside and measured blood pressure by the cuff method four times. Arrows indicate beginning and end of visit, ABP pulsatile arterial blood pressure, MAP mean arterial blood pressure, ʃABP arterial blood pressure integrated over regular time period, HR heart rate (From Mancia et al. [19], by courtesy of Lancet)

9.3 Birth of “White Coat Hypertension”

When were the terms “white coat effect” and “white coat hypertension” coined and successfully entered into the medical literature? The first mention I could find of “white coat hypertension” is in a paper by Pickering’s group in 1984 [21]: “The anxiety provoking experience of an office visit may cause a transient rise in BP, which we have designated white-coat hypertension”. Although in that sentence the authors cite two previous papers of theirs [22, 23] in which they would have used the term, I have been unable to find the term in these two articles, but both papers explicitly attribute the difference between the clinic and ambulatory or home BP values to “the defense reaction in hypertensive subjects which causes a rise of BP during a visit to a physician’s office” [22].

Spreading of the term was apparently an unwanted consequence of our demonstration of the BP raising effect of the doctor’s presence to measure BP. Indeed, in a 1985 paper, Pickering et al. [24] wrote: “this pressor effect of a physician, often referred to as white coat hypertension was most dramatically illustrated in a recent study by Mancia and colleagues…”. Although this is only the second occasion, to my knowledge, that the term white coat hypertension was used in the medical literature, the way it was reported in the paper by Pickering et al. [24] (“often referred to as…”) means it was already used in current medical language. Three years later, in 1988, the term “white coat hypertension” was already in the title of a paper by Pickering’s group [25], with the meaning that became commonly accepted thereafter of a patient with elevated blood pressures in the clinic who has normal daytime ambulatory pressures or normal blood pressure at home measurements. In 1993, the term “white coat hypertension” triumphantly entered into the Fifth Report of the Joint National Committee (JNC V) [26].

While the finding that there are patients whose BP is in the hypertensive range when measured in the office but not in out-of-office measurements is undoubtedly useful in clinical practice, the correctness of the term “white coat hypertension” has been debated. In a 1996 editorial, Mancia and I [27] summarized the arguments against interpreting the clinic-daytime ambulatory blood pressure difference as an accurate reflection of the blood pressure rise induced by a doctor’s intervention in the measurement, that is what can properly be described as the real “white coat effect”: (a) the real white coat effect is characterized both by a blood pressure increase and by a tachycardia, whereas the clinic-daytime ambulatory blood pressure difference is not accompanied by any similar difference in heart rate; (b) the real white coat effect has been shown to be independent of the patient’s age and clinic blood pressure, whereas the clinic-daytime ambulatory blood pressure difference increases progressively with ageing and clinic blood pressure values; and (c) in hypertensive patients there appears to be no significant correlation between the white coat effect assessed directly by continuous blood pressure measurements before, during and after a doctor’s visit and the clinic-daytime ambulatory blood pressure difference. We concluded that “the term white coat hypertension, based as it is on an interpretation of the cause of the difference between clinic and daytime ambulatory blood pressure, is a misnomer because this difference does not measure the white coat effect and may be caused by several other mechanisms; it also underlies a misconception, because the interpretation that white coat hypertension is purely emotional in nature is, at best, unproven [27].

The 1996 World Health Organization report on Hypertension Control suggested a more descriptive term “isolated clinic (or office) hypertension” [28], that was certainly more appropriate to our state of ignorance. This term was recommended in the 1999 World Health Organization/International Society of Hypertension guidelines on the management of hypertension [29] and also reported in all European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology Hypertension guidelines [30–32]. This was definitely a lost war. The term “white coat hypertension” combined the winning aspects of reassuring the experts and the doctors with the (false) belief they knew what they were talking about and the patients with the (equally false) belief theirs was a false hypertension. The term “white coat” could be easily translated in all major languages (e.g. blouse blanche, bata blanca, camice bianco, etc.) and even resisted the current trend to a change in colour of the doctor’s or nurse’s coat. A consultation of Scopus in April 2014 gives 491 references the title of which used the term “white coat hypertension” and only 20 and 19 references, respectively, using the term “isolated clinic hypertension” or “isolated office hypertension”. A final witness of this lost war is the surrender to the use of “white coat hypertension” in the title of this volume.

9.4 The Physician’s Fault or the Statistician’s?

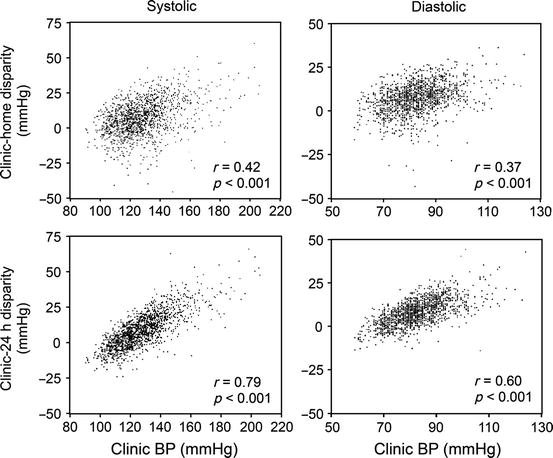

Does a lost war mean a war for a wrong cause? The perplexities expressed in 1996 about the real nature of the clinic-ambulatory BP difference [27, 28] have been strengthened by further research. In the PAMELA population study, in which all individuals with a wide range of clinic BP values had clinic, ambulatory and home BP measurements, we found the clinic-ambulatory (as well the clinic-home) BP differences were directly proportional to clinic BP values, in such a way that the difference (i.e. the so-called white coat effect) was progressively smaller the lower was office BP [33] (Fig. 9.3). This finding has recently been replicated in an analysis of data from the European Lacidipine Study on Atherosclerosis (ELSA), in which all hypertensive patients were followed up both by clinic and ambulatory BP measurements [34]. This type of relationship can also be found in some of the papers investigating the “white coat effect” (see, e.g. Fig. 1 in the paper by Kleinent et al. [21] and Fig. 2 in the paper by Hoegholm et al. [35]), but was not remarked by the authors, and no conclusion was drawn from this finding. A regression line of ambulatory over office BP values was also derived by Perloff et al. [36] in the paper in which they described the better prognostic value of ambulatory BP, but they used the equation only to identify those patients whose ambulatory BP was higher than expected and were found to have higher incidence of cardiovascular events. The statistical meaning of the regression was not remarked or discussed.