Primary carcinomas of the vagina represent 1–2% of malignant neoplasms of the female genital tract. In the United States, it is estimated that there will be 3,170 new cases diagnosed in 2014, and 880 deaths from the disease (1). Incidence rates in the United States from 1998 through 2003 were 0.18 per 100,000 female population for in situ cases, and 0.69 per 100,000 females for invasive cases; median ages were 58 and 68 years, respectively (2). Unlike cervical cancer, more than 50% of patients are diagnosed in the seventh, eighth, and ninth decades of life. Like cervical cancer, squamous cell histology accounts for 70–80% of cases (2,3).

Until the late 1930s, vaginal cancer was in general considered to be incurable. Most patients presented with disease that had spread beyond the vagina, and radiation therapy techniques were poorly developed. With modern radiation therapy techniques, cure rates of even advanced cases should now be comparable with those for cervical cancer (4–6). According to the 26th International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) Annual Report, the overall 5-year survival rate has increased from 34.1% between 1959 and 1963 to 53.6% between 1999 and 2001 (3).

Fu (7) reported that 84% of carcinomas involving the vagina were secondary, usually from the cervix (32%); endometrium (18%); colon and rectum (9%); ovary (6%); or vulva (6%). Of 164 squamous cell carcinomas, 44 (27%) were primary and 120 (73%) were secondary. Among the latter, 95 (79%) originated from the cervix; 17 (14%) from the vulva; and 8 (7%) from the cervix and the vulva. This apparent discrepancy is partly related to the FIGO classification and staging of malignant tumors of the female pelvis. The staging requires that a tumor that has extended to the portio and reached the area of the external os should be regarded as a carcinoma of the cervix, whereas a tumor that involves the vulva and vagina should be classified as a carcinoma of the vulva. Endometrial carcinomas and choriocarcinomas commonly metastasize to the vagina, whereas tumors from the bladder or rectum may invade the vagina directly.

Primary Vaginal Tumors

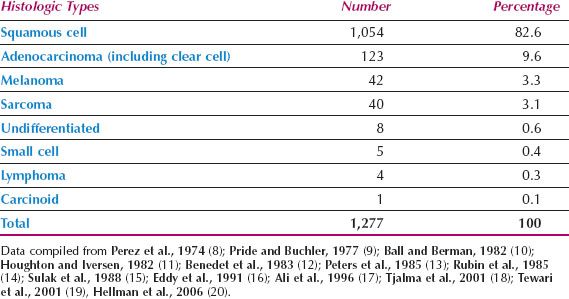

The histologic types of primary vaginal tumors are shown in Table 14.1 (8–20). Squamous cell carcinomas are the most common, although adenocarcinomas, melanomas, and sarcomas are also seen.

Table 14.1 Primary Vaginal Cancer: Reported Incidence of Histologic Types

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common vaginal cancer. The mean age of the patients is approximately 67 years, although the disease occasionally is seen in the third and fourth decades of life (6,8,11,14). About 80% of patients are older than 50 years (3).

Etiology

Women who have been treated for a prior anogenital cancer, particularly of the cervix, have a high relative risk of developing vaginal cancer, although the absolute risk is low (21).

In a population-based study of 156 women with in situ or invasive vaginal cancer, Daling et al. determined that they had many of the same risk factors as patients with cervical cancer, including a strong relationship with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection (21). The presence of antibodies to HPV 16 was strongly related to this risk. A study of 341 cases from the Radiumhemmet reported that the disease seemed to be etiologically related to cervical cancer, and thus HPV infection, in young patients, but in older patients, there was no such association (22). The rate of vaginal HPV infection in women posthysterectomy is similar to the rate of cervical HPV infection in women who have a uterus. The relative rarity of invasive vaginal cancer suggests that the cervical transformation zone is an important, but not necessary, factor in malignant transformation (23).

As many as 30% of patients with primary vaginal carcinoma have a history of in situ or invasive cervical cancer treated at least 5 years earlier (10,15,17). In a report from the University of South Carolina (11), a past history of invasive cervical cancer was present in 20% of the cases and of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) in 7%. The median interval between the diagnosis of cervical cancer and the diagnosis of vaginal cancer was 14 years, with a range of 5 years, 8 months to 28 years. Sixteen percent of the patients had a history of prior pelvic irradiation.

There are three possible mechanisms for the occurrence of vaginal cancer after cervical neoplasia:

1. Occult residual disease

2. New primary disease arising in an “at-risk” lower genital tract

3. Radiation carcinogenicity

Colposcopy of the vagina should always be performed before surgical treatment for cervical cancer, and this should detect any extension of intraepithelial neoplasia from the cervix to the upper vagina. Adequate vaginal margins should be taken, and occult residual disease prevented.

There is controversy regarding the distinction between a new primary vaginal cancer and a recurrent cervical cancer. Some authorities use a 5-year cutoff because 95% of cervical cancer recurrences will occur within this period (24–26) but others prefer a 10-year interval (12).

Prior pelvic radiation therapy has been considered a possible cause of some vaginal carcinomas (22,27). In a series of 314 patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina reported from Sweden, 44 (14%) had received previous pelvic or vaginal radiation 5 to 55 years earlier. Although in many cases the radiation had been given for another HPV-related cancer, in 22 cases, the previous radiation had been for uterine or ovarian cancers (22). Judicious use of pelvic radiation may be particularly important in young patients, who may live long enough to develop a second neoplasm in the irradiated vagina (27).

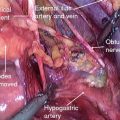

Figure 14.1 Squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina in a patient with a procidentia. The cancer was apparently related to long-term pessary use.

The true malignant potential of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) is unclear because after diagnosis, the condition is usually treated. Benedet and Saunders (28) reviewed 136 cases of carcinoma in situ of the vagina seen over a 30-year period. Four cases (3%) progressed to invasive vaginal cancer in spite of various methods of treatment. Rome and England reported 9 cases (6.8%) of early invasive vaginal cancer detected during the initial management of 132 cases of VAIN (29).

Chronic local irritation from long-term use of a pessary may be associated with vaginal cancer (Fig. 14.1) (7), although pessaries are used less commonly in modern gynecology.

Screening

For screening to be cost effective, the incidence of the disease must be sufficient to justify the cost of screening. In the United States, the age-adjusted incidence of vaginal cancer is 0.6 per 100,000 women, making routine screening of all patients inappropriate (30). Women with a history of cervical intraepithelial or invasive neoplasia are at increased risk, and should be monitored with Pap smears and careful examination of the entire vagina.

As many as 59% of patients with a vaginal cancer have had a prior hysterectomy (5,10), but when age and prior cervical disease are controlled for, there is no increased risk of vaginal cancer in women who have had a hysterectomy for benign disease (31).

Symptoms and Signs

Most patients with vaginal cancer present with painless vaginal bleeding and discharge. The bleeding is usually postmenopausal but may be postcoital. In the large series reported from the Radiumhemmet, 14% of patients were asymptomatic, and the diagnosis was made either by routine examination (7%) or by abnormal cytology (7%) (20).

Because the bladder neck is close to the vagina, bladder pain and frequency of micturition occur earlier than with cervical cancer. Posterior tumors may produce tenesmus. Approximately 5% of patients present with pelvic pain because of extension of disease beyond the vagina.

Most lesions are situated in the upper one-third of the vagina, usually at the apex or on the posterior wall (21,22,25–27,32). Macroscopically, the lesions are usually exophytic (fungating or polypoid), but they may be endophytic. Surface ulceration usually occurs late in the course of the disease.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of carcinoma of the vagina is easily missed on first examination, particularly if the lesion is small and situated in the lower two-thirds of the vagina, where it may be covered by the blades of the speculum. Definitive diagnosis is usually made by biopsy of a gross lesion, which can often be performed in the office without anesthesia. In elderly patients or in those with some degree of vaginal stenosis, examination under anesthesia may be necessary to allow adequate biopsy and clinical staging. The latter may require cystoscopy or proctoscopy, depending on the location of the tumor.

In patients with an abnormal Pap smear and no gross abnormality, careful vaginal colposcopy and the liberal use of Lugol iodine to stain the vagina are necessary. This is initially performed in the office, but may need to be repeated with the patient under regional or general anesthesia to allow excision of colposcopically abnormal areas.

For definitive diagnosis of early vaginal carcinoma, it may be necessary to resect the entire vaginal vault and submit it for careful histologic evaluation, because the lesion may be partially buried by closure of the vault at the time of hysterectomy. This is usually done with a cold knife, but Fanning et al. have reported the successful use of the loop electrosurgical procedure for partial upper vaginectomy in 15 patients (33). Inadvertent cystotomy may occur, and this requires immediate repair.

Hoffman et al. at the University of South Florida reported on 32 patients who underwent upper vaginectomy for VAIN 3 (34). Occult invasive carcinoma was found in nine patients (28%). In five cases, the depth of invasion was less than 2 mm, but in four cases, invasion ranged from 3.5 mm to full-thickness involvement.

Staging

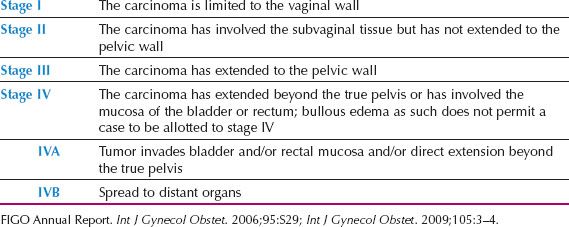

The FIGO staging for vaginal carcinoma is shown in Table 14.2. The staging is clinical and is based on the findings at general physical and pelvic examination, cystoscopy, proctoscopy, chest x-ray, and possible skeletal radiographs if the latter are indicated because of bone pain.

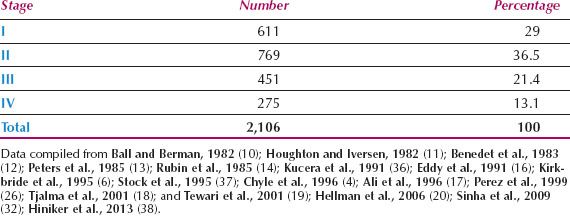

Because it is difficult to determine accurately any spread into subvaginal tissues, particularly from anterior or posterior lesions, observer differences are common. This is reflected in the wide range of stage distributions reported and the wide range of survival rates within a given stage. The distribution by FIGO stage from 16 series is shown in Table 14.3. Less than one-third of patients present with disease confined to the vagina, although Hellman et al. reported that significantly more patients were diagnosed at an early stage in the last 20 years of their study, compared to the first 20 years (20).

Table 14.2 Carcinoma of the Vagina: FIGO Nomenclature

Because there have been no clinical series correlating the risk of lymph node involvement with the depth of invasion, there is no official definition of microinvasive disease. Peters et al. (35) suggested the following criteria for microinvasive carcinoma of the vagina: focal invasion associated with VAIN 3, no lymph-vascular invasion, free margins on partial or total vaginectomy, and a maximum depth of invasion of less than 2.5 mm, measured from the overlying surface. Eddy et al. (39) reported six patients who met these criteria and were treated by either partial or total vaginectomy. In one of the six, a bladder recurrence developed at 35 months.

Table 14.3 Primary Vaginal Carcinoma: Distribution by Stage of Disease

Patterns of Spread

Vaginal cancer spreads by the following routes:

1. Direct extension to the pelvic soft tissues, adjacent organs (bladder and rectum), and pelvic bones.

2. Lymphatic dissemination to the pelvic, and later the para-aortic lymph nodes. Lesions in the distal one-third of the vagina may metastasize directly to the inguinofemoral lymph nodes, with the pelvic nodes involved secondarily, or they may spread directly to pelvic nodes. Posterior vaginal lesions may involve perirectal nodes.

Using lymphoscintigraphy, pretreatment lymphatic mapping and sentinel node identification were performed in 11 patients at the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. Five patients (45%) had sentinel nodes identified in the groin only, four (36%) in the pelvis only, and two (18%) had sentinel nodes identified in both the groin and the pelvis (40). No relationship was observed between sentinel node location and primary tumor location.

3. Hematogenous dissemination to distant organs, including lungs, liver, and bone. Hematogenous dissemination is usually a late phenomenon in vaginal cancer, and the disease usually remains confined to the pelvis for most of its course.

There is little information available on the incidence of lymph node metastases in vaginal cancer, because most patients are treated with radiation therapy. Rubin et al. (14) reported that 16 of 38 patients (42.1%) with all stages of disease had lymphangiographic abnormalities, but many of these abnormalities were not confirmed histologically. Al-Kurdi and Monaghan (41) performed lymph node dissections on 35 patients and reported positive pelvic nodes in 10 patients (28.6%). Positive inguinal nodes were present in 6 of 19 patients (31.6%), with disease involving the lower vagina. Stock et al. reported positive pelvic nodes in 10 of 29 patients (34.5%) with all stages of disease who underwent bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy as part of their therapy or staging. Positive para-aortic nodes were present in one of eight patients (12.5%) undergoing para-aortic dissection (37).

Preoperative Evaluation

Apart from the standard staging investigations, a computed tomographic (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the pelvis and abdomen is useful for evaluation of the status of the primary tumor, liver, pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes, and ureters. A high-quality pelvic MRI usually gives better definition of the extent of the primary tumor than CT, and is particularly helpful in detecting bladder or rectal infiltration. However, MRI can underestimate the extent of rectal mucosal infiltration, and must always be supplemented with a careful pelvic examination prior to treatment planning.

The group in St. Louis compared CT and F-18 fluorodeoxy glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) for the detection of the primary tumor and lymph node metastases in patients with carcinoma of the vagina (42). In a series of 21 patients with an intact primary tumor, CT demonstrated abnormally enlarged lymph nodes in 17%, while 35% had abnormal uptake with FDG-PET. In the same series, CT visualized the primary tumor in only nine cases (43%), while FDG-PET demonstrated abnormal uptake at the primary site in all 21 (100%). Uptake in the bladder can obscure the extent of disease, particularly in the region of the anterior vaginal wall.

Treatment

Experience with the management of primary vaginal cancer is limited by the rarity of the disease. Most gynecologic oncology centers in the United States see only two to five new cases per year, and even in some European centers, where referral of oncology cases tends to be more centralized, only one new case per month can be expected (43). Therapy must be individualized, and varies depending on the stage of disease and the site of vaginal involvement, further limiting physician experience.

Anatomic factors and psychological considerations place significant constraints on treatment planning. The proximity of the vagina to the rectum, bladder, and urethra limits the dose of radiation that can be safely delivered, and restricts the surgical margins that can be attained, unless an exenterative procedure is performed. For most patients, maintenance of a functional vagina is an important factor in the planning of therapy.

Primary Surgery

Primary surgery has a limited role in the management of patients with vaginal cancer because of the radicality required to achieve clear surgical margins, but in selected cases, satisfactory results can be achieved (20,32,37,40,44–46). Surgery may be useful in the following circumstances:

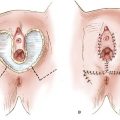

1. In patients with stage I disease involving the upper posterior vagina. If the uterus is still in situ, these patients require radical hysterectomy, partial vaginectomy, and bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy. If the patient has had a hysterectomy, radical upper vaginectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy can be performed after development of the paravesicular and pararectal spaces and dissection of each ureter out to its point of entry into the bladder.

A Chinese report described four patients who had laparoscopic radical hysterectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, and total vaginectomy for stage I vaginal carcinoma (45). Vaginal reconstruction was performed using the sigmoid colon. All patients were clinically free of disease with a mean follow-up of 46 months (range 40 to 54 months).

A surgical approach to conserve reproductive and sexual function was described from Italy (46). Three nulliparous women under 40 years of age with stage I squamous cell carcinoma confined to the upper third of the vagina underwent radical tumorectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. A fourth patient underwent partial hemivaginectomy plus ipsilateral paracolpectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. One patient with microscopic involvement of the paracolpium received adjuvant radiation after laparoscopic ovarian transposition. With a follow-up of 9 to 51 months, all patients were regularly menstruating, sexually active, and clinically free of disease.

Although this approach has obvious appeal, the number of cases is very limited, and such an approach should be limited to small lesions, particularly if located in the upper vagina. The authors recommended more intensive follow-up, particularly aimed at early detection of any locoregional relapse or a second tumor of the lower genital tract (46).

2. In young patients who require radiation therapy. Pretreatment laparotomy or laparoscopy in such patients may allow ovarian transposition, surgical staging, and resection of any lymph nodes larger than 2 cm diameter.

3. In patients with stage IVA disease, particularly if a rectovaginal or vesicovaginal fistula is present. Primary pelvic exenteration is a suitable treatment option for such patients, provided they are medically fit, and the tumor is not fixed to the pelvic sidewall. Eddy et al. (16) reported a 5-year disease-free survival in three of six patients with stage IVA disease treated with preoperative radiation followed by anterior or total pelvic exenteration. In sexually active patients, vaginal reconstruction should be performed simultaneously.

4. In patients with a central recurrence after radiation therapy. Surgical resection, which usually necessitates pelvic exenteration, is the only option for this group of patients.

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy followed by Radical Surgery

Benedetti Panici et al. from Italy reported 11 patients with FIGO stage II vaginal cancer who were treated with paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 and cisplatin 75 mg/m2 every 21 days for three courses, followed by radical hysterectomy, radical vaginectomy, and pelvic lymphadenectomy. If the distal third of the vagina was involved, an inguinal-femoral lymphadenectomy was also performed (44). One patient had a positive pelvic node and received external pelvic radiation. Three patients (27%) achieved a complete clinical response and seven (64%) a partial clinical response to the chemotherapy. With a median follow-up of 75 months, nine patients (82%) remained free of disease.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is the treatment of choice for all patients except those previously listed. In most cases, a combination of teletherapy and intracavitary or interstitial brachytherapy is used to achieve optimal control rates (4–6,8,19,20,26,37). Although several reports suggest that local control can sometimes be achieved with brachytherapy alone for highly selected stage I and II lesions, local recurrence rates of 20–30% are higher than expected for these early lesions and suggest that some treatment with external beam is usually indicated (5,6,26,47). For larger lesions, treatment is usually started with approximately 4,000 to 5,000 cGy of external beam irradiation to treat the pelvic lymph nodes and to obtain initial shrinkage of primary tumor. Radiation fields should be carefully tailored to the primary site and must take into account movement of the vagina with variations in bladder and rectal filling. Radiopaque fiducial markers inserted in the vagina assist in external beam treatment planning and document the original extent of disease for brachytherapy planning. If the distal one-third of the vagina is involved, the groin nodes should be treated. As with cervical cancer, patients who have involved common iliac or para-aortic nodes should be treated with extended fields.

The most challenging part of treatment is the final boost treatment that must be given to achieve control of initial sites of gross disease. A wide variety of highly specialized techniques can be used to deliver additional radiation to the primary site, while minimizing the dose to adjacent critical structures. In most cases, this additional dose is achieved using intracavitary or interstitial brachytherapy.

If the uterus is intact and the lesion involves the upper vagina, an intrauterine tandem and appropriate vaginal applicator can be used. In patients who have had a hysterectomy, superficial apical lesions may be treated using a vaginal domed cylinder. A cylinder with peripheral channels may be used for superficial lesions in the midvagina. Because of its steep fall-off in radiation dose deep to a cylinder, intracavitary treatment should rarely be used for lesions that are thicker than 3 to 5 mm at the time of brachytherapy. Interstitial brachytherapy techniques permit coverage of more deeply invasive lesions; however, when interstitial therapy is used for apical lesions, laparoscopy or open guidance may be needed (5,19,26).

In general, brachytherapy is preferred over an external beam boost if the tumor target volume can be adequately covered without overdosing critical structures. When the location of the target makes it impossible to treat the entire tumor to high dose without placing needles in or very close to critical structures, it may be better to complete the treatment using highly conformal techniques, such as intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). In particular, massive, fixed tumors and tumors that involve the rectovaginal septum or bladder may be treated more effectively with additional external beam irradiation using IMRT.

There is limited reported experience with chemoradiation for vaginal cancer (6,48), although many centers routinely use this combined therapy, as is being done for cervical carcinoma. In our centers, cisplatin 35 to 40 mg/m2 given on the first day of each week of external beam therapy is used. The small number of cases makes it virtually impossible to conduct a randomized, prospective study to compare standard radiation with chemoradiation for patients with vaginal cancer.

Complications of Therapy

Major complications of therapy are usually reported in 10–15% of patients treated for primary vaginal cancer, whether the treatment is by surgery or radiation. Extensive tumor involvement can cause tissue injury and scarring, but the close proximity of the rectum, bladder, and urethra predispose these structures to treatment-related injuries in the form of radiation cystitis, radiation proctitis, recto or vesicovaginal fistulas, and rectal strictures or ulceration. Frank et al. (5) reported overall actuarial rates of major complications of 10% and 17% at 5 and 10 years, respectively. Eight of 11 major rectal complications occurred in patients whose tumors involved the posterior wall and all of the major bladder complications occurred in patients whose tumors involved the anterior wall. The risk of major complications was also strongly correlated with tumor stage and with a history of smoking. The risk of functional damage to the vagina after treatment of vaginal cancer is high, particularly for patients with large, destructive cancers. Localized radiation necrosis is occasionally seen during the first 3 to 6 months after treatment but fibrosis and vaginal stenosis are more common causes of sexual dysfunction.

Stryker (49) reported vaginal morbidity in 9 of 15 patients (60%) undergoing external beam therapy plus intracavitary brachytherapy, and 3 of 10 patients (30%) undergoing external beam therapy plus interstitial brachytherapy. He suggested that when combining external beam therapy with brachytherapy, interstitial techniques were preferable, although the probability of late vaginal morbidity may be related to radiation dose rate and radiation fractionation, as well as technique. These factors vary widely between practitioners, and detailed quality-of-life studies comparing outcome with tumor characteristics and treatment techniques are needed.

Patients who are sexually active should be encouraged to continue regular intercourse, but those who are not sexually active, or for whom intercourse is temporarily too painful, should be encouraged to use topical estrogen and a vaginal dilator, at least every second night.

Prognosis

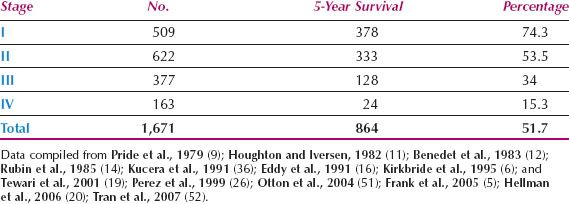

A compilation of large published series reveals a mean overall 5-year survival rate for vaginal cancer of about 52%, which reflects the challenges involved in treating this disease, and the late stage at presentation (Table 14.4). For patients with stage I disease, the 5-year survival rate in combined series is approximately 74%. In the 26th volume of the FIGO Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer, the 5-year survival for 224 patients with vaginal cancer was as follows: Stage I, 77.6%; stage II, 52.2%; stage III, 42.5%; stage IVA, 20.5%; stage IVB, 12.9% (3).

Better results have been reported from individual centers. In a report of 193 cases of primary vaginal squamous cell carcinoma from the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Frank et al. reported 5-year disease-specific survival rates of 85% for 50 patients with FIGO stage I disease, 78% for 97 patients with stage II, and 58% for 46 patients with stages III to IV (5). Five-year disease-specific survival rates were 82% and 60% for patients with tumors ≥4 cm and >4 cm, respectively (p = 0.0001). Kirkbride et al. (6) from the Princess Margaret Hospital in Toronto reported on 138 patients with invasive vaginal carcinoma. The 5-year cause-specific survival rates by stage were 77% for stages I/II and 56% for stages III/IV. In a multivariate analysis, only tumor size and stage of disease were significant variables.

Most recurrences of vaginal cancer are in the pelvis (50), so high-quality radiation therapy including brachytherapy performed by an experienced brachytherapist and possibly concurrent chemotherapy may improve the results. Chyle et al. (4) reported that cure after first relapse was uncommon, with a 5-year survival rate of only 12%.

Because of the rarity of the disease, patients with vaginal cancer should be referred centrally to a limited number of tertiary referral units so that increasing experience can be gained in their management.

Table 14.4 Primary Vaginal Carcinoma: 5-Year Survival Rates

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree