Vulvar cancer represents about 5% of malignancies of the female genital tract and 0.6% of female cancers. There were estimated to be 4,850 new cases of vulvar cancer diagnosed in the United States in 2014 and 1,030 deaths (1). Squamous cell carcinomas account for 85–90% of cases, whereas basal cell carcinomas, melanomas, invasive Paget’s disease, Bartholin gland carcinomas, and sarcomas are much less common.

Vulvar cancer is predominantly a disease of older women. In spite of the vulva being an external organ, delayed diagnosis has been typical of this disease.

There has been a significant increase in the incidence of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) in recent decades (2–5), and this has been attributed to changing sexual behavior, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, and cigarette smoking (6). Judson et al. (2) reviewed 13,176 in situ and invasive vulvar carcinomas from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results program (SEER) database over a 28-year period (1973 to 2000); 57% of the cases were in situ. There was a 411% increase in the incidence of in situ carcinoma from 1973 to 2000, while the incidence of invasive carcinoma increased 20% during the same period. The incidence of in situ disease increased until the age of 40 to 49 years, and then decreased, whereas the invasive cancer risk increased with age, and increased more rapidly after age 50. Similar trends have been reported from Denmark, although the increased incidence of invasive vulvar cancer was limited there to women under the age of 60 years (5).

Hampl et al. (3) from Dusseldorf reported that the fraction of vulvar cancers diagnosed in women under the age of 50 years increased from 11% in the 1980s to 41% in the 10 years up to 2007 in their single institution study. Population based SEER data from the United States have shown no comparable increase in incidence. From 1980 to 1989, 15% of 2,271 invasive vulvar cancers occurred in women under the age of 50 years, compared to 18.8% of 5,227 vulvar cancers from 2000 to 2005 (7).

Approximately 40% of vulvar cancers are HPV positive, and about 85% of HPV-positive invasive vulvar cancers are attributable to HPV-16 (8). Prophylactic HPV vaccines have the potential to decrease the incidence of invasive vulvar cancer by about one-third overall (8), and to be even more effective in younger women.

In the early part of the 20th century, patients commonly presented with advanced disease, and surgical techniques were poorly developed; thus, the 5-year survival rate for vulvar cancer was 20–25% (9,10). Basset (11), in France, was the first to suggest an en bloc dissection of the vulva, groin, and iliac lymph nodes, although he performed the operation only on cadavers. Taussig (12), in the United States, and Way (13), in Great Britain, pioneered the radical en bloc dissection for vulvar cancer, and reported 5-year survival rates of 60–70%. Postoperative morbidity was high after these procedures, with wound breakdown, infection, and prolonged hospitalization the norm. For patients with disease involving the anus, rectum, or proximal urethra, pelvic exenteration was often combined with radical vulvectomy.

Since approximately 1980, there has been a paradigm shift in the approach to vulvar cancer (14,15). The most significant advances have included the following:

1. Individualization of treatment for all patients with invasive disease (16,17).

2. Vulvar conservation for patients with unifocal tumors and an otherwise normal vulva (16–20).

3. Omission of the groin dissection for patients with T1 tumors and no more than 1 mm of stromal invasion (16,17).

4. Elimination of routine pelvic lymphadenectomy (21–25).

5. The use of separate groin incisions for the groin dissection to improve wound healing (26).

6. Omission of the contralateral groin dissection in patients with lateral T1 lesions and negative ipsilateral nodes (16,17,23).

7. The use of preoperative radiation therapy or definitive radiation therapy to obviate the need for exenteration in selected patients with advanced disease (27–30).

8. The use of postoperative radiation to decrease the incidence of groin recurrence and improve survival of patients with multiple positive groin nodes (25).

9. Resection of bulky positive groin and pelvic nodes without complete node dissection to decrease the risk of lymphedema prior to pelvic and groin radiation (31).

10. The use of sentinel node biopsy to obviate the need for complete groin dissection in carefully selected patients with early vulvar cancer (32).

This paradigm shift in the management philosophy of vulvar cancer has been well exemplified in retrospective reviews of the experience at the University of Miami (33) and the Mayo Clinic (34). Both centers reported a trend toward a more conservative approach, and both reported decreased postoperative morbidity, without compromised survival.

Etiology of Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma

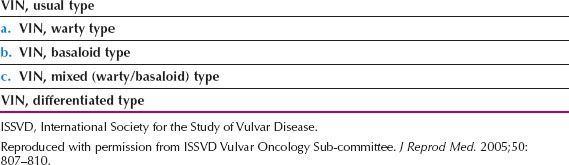

VIN has traditionally been considered to be a premalignant condition, and to be one disease, but in 2004, the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease officially divided VIN into two types: (i) usual type VIN, which is related to HPV infection, and (ii) differentiated VIN, which is unrelated to HPV infection (Table 13.1) (35). The term VIN 1 is no longer used, and VIN 2 and VIN 3 are simply called VIN.

The older classification of VIN 1, 2, and 3 was based on the degree of histologic abnormality, but there is no evidence that the VIN 1 to 3 morphologic spectrum reflects a biologic continuum, or that VIN 1 is a cancer precursor (35).

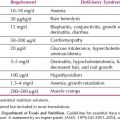

Table 13.1 Squamous Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia (VIN). 2004 ISSVD Terminology

It is now generally accepted that there are two different etiologic types of vulvar cancer (36,37). One type is seen mainly in younger patients, is related to HPV infection and smoking, and is commonly associated with basaloid or warty VIN (36–38). The more common type is seen mainly in elderly patients, is unrelated to smoking or HPV infection, and concurrent VIN is uncommon. There is, however, a high incidence of dystrophic lesions, including lichen sclerosus and squamous hyperplasia, adjacent to the tumor (39–41). If VIN is present, it is of the differentiated type (42–44).

Using data on 2,685 patients with invasive vulvar cancer from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results program (SEER), Sturgeon et al. (45) reported the increased risk of a subsequent cancer to be 1.3-fold. Most of the second cancers were related to smoking (i.e., cancers of the lung, buccal cavity, pharynx, nasal cavity, or larynx) or to infection with human papillomavirus (e.g., cervix, vagina, or anus).

In a study designed to investigate the malignant potential of the vulvar premalignant conditions, Eva et al. (44) identified 580 women from Birmingham, England, who had vulvar biopsies showing VIN, lichen sclerosus, or squamous hyperplasia over a 5-year period. These women were studied for the presence of a synchronous or metachronous vulvar cancer. The authors reported that differentiated VIN had a higher risk of malignancy (85.7%) than usual VIN (25.8%), lichen sclerosus (27.7%) or squamous hyperplasia (31.7%).

Dutch workers retrieved all patients with a primary diagnosis of VIN from the Nationwide Netherlands Database between 1992 and 2005 (43). They reported that the incidence of both usual and differentiated VIN increased during the study period, while the incidence of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma remained stable. In this prospective study, they found the malignant potential of these premalignant conditions to be much lower—5.7% for usual VIN, 32% for differentiated VIN, and 2–6% for lichen sclerosus (43). However, Jones et al. (46) reported a series of 405 cases of VIN 2–3 seen between 1962 and 2003 in Auckland, New Zealand. Progression to malignant disease occurred between 1.1 and 7.3 years (mean 3.9 years) in 10 of 16 untreated patients (62.5%), but in only 17 treated women (3.8%).

Patients with lichen sclerosus and concomitant hyperplasia may be at particular risk for malignant transformation. Rodke et al. (47) reported the development of vulvar carcinoma in 3 of 18 such cases (17%), postulating that the areas of hyperplasia were superimposed on a background of lichen sclerosus because of chronic irritation and trauma.

Carli et al. (48) from the Vulvar Clinic at the University of Florence, Italy, reported an association with lichen sclerosus in 32% of their cases of vulvar cancer that were not HPV related. They felt that the existence of accessory conditions necessary to promote the progression from lichen sclerosus to cancer remained to be established. Scurry believes lichen sclerosus contributes to a vicious cycle of itching and scratching, which leads to superimposed lichen simplex chronicus, squamous cell hyperplasia, and ultimately carcinoma (40).

The management of VIN is discussed in Chapter 7.

Paget’s Disease of the Vulva

The original description of Paget’s disease was of a breast lesion (Sir James Paget, 1874), in which the appearance of the nipple heralded an underlying carcinoma. Extramammary Paget’s Disease is a rare neoplasm of the skin, which is estimated to account for 1–6% of all cases of Paget’s disease. It predominantly affects women over 60 years of age (49) and the vulva accounts for up to 60% of cases (50).

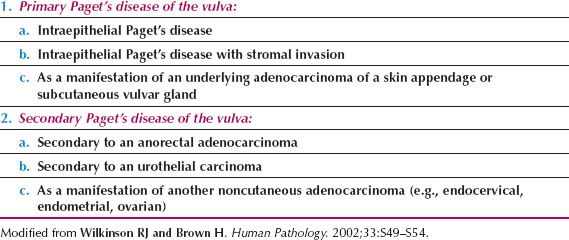

Paget’s disease of the vulva has been the subject of two recent classifications, and that proposed by Wilkinson and Brown (51) in 2002 is shown in Table 13.2. In this classification, Type 1 Paget’s disease is of primary cutaneous origin, and is divided into Type 1a, primary intraepithelial neoplasia; Type 1b, intraepithelial neoplasia with underlying invasion; and Type 1c, a manifestation of an underlying adenocarcinoma of a skin appendage or of vulvar glandular origin. Type 2 Paget’s disease is of noncutaneous origin, such as the rectum, bladder, or upper genital tract.

In the Kurman classification, Type 2 Paget’s disease is a manifestation of an associated primary cancer or a rectal adenocarcinoma, and Type 3 is a manifestation of a urothelial neoplasm (52).

Table 13.2 Classification of Paget’s Disease of the Vulva

Type 1 Paget’s Disease

In a review of Type 1 cases from the English literature, Niikura et al. (53) reported on 565 cases, including their own series of 22 cases. There were 425 patients (75%) with Type 1a disease; 89 (16%) with Type 1b; and 51 (9%) with Type 1c.

MacLean et al. (54) reported that 6 of 76 patients (8%) on a British registry had an underlying carcinoma (Type 1b), and 14 patients (18.4%) had a systemic cancer. The primary was in the breast in six; bladder in three; and colorectum, cervix, uterus, and ovary in one each. One patient had a melanoma. Only four of these tumors were synchronous cancers. Niikura et al. (53) determined that if only synchronous neoplasms or those occurring within 12 months of the diagnosis were considered, only 8% of patients (44 of 534) with primary Paget’s disease had a nonvulvar malignancy.

Fanning et al. (49) reported on a combined series of 100 patients with Paget’s disease of the vulva. Their median age was 70 years. There was a 12% prevalence of invasive vulvar Paget’s disease, and a 4% prevalence of associated vulvar adenocarcinoma. Thirty-four percent of patients experienced a recurrence at a median of 3 years.

Clinical Features

The disease predominantly affects postmenopausal white women, and the presenting symptoms are usually pruritus and vulvar soreness. The lesion has an eczematoid appearance macroscopically and usually begins on the hair-bearing portions of the vulva (Fig. 13.1). It may extend to involve the mons pubis, thighs, and buttocks. Extension to involve the mucosa of the rectum, vagina, or urinary tract also has been described (55). The more extensive lesions are usually raised and velvety in appearance and may weep persistently.

Investigations

All patients with Paget’s disease of the vulva should be screened for any associated malignancy. These investigations should include mammography, computed tomography (CT) scan of the pelvis and abdomen, transvaginal ultrasonography, and cervical cytology. If the lesions involve the anus, colonoscopy should be undertaken, while if the urethra is involved, cystoscopy is indicated.

Treatment

The mainstay of treatment is wide superficial resection of the gross disease (56,57). Underlying adenocarcinomas usually are clinically apparent, but this is not invariable. Paget cells may invade the underlying dermis, which should be removed for adequate histologic evaluation. For this reason, laser therapy is unsatisfactory for primary Paget’s disease. The surgical defect can usually be closed primarily, but sometimes a split thickness skin graft may be required to cover an extensive defect.

Unlike squamous cell carcinoma in situ, in which the histologic extent of disease usually correlates reasonably with the macroscopic lesion, Paget’s disease usually extends well beyond the gross lesion, resulting in frequent positive surgical margins. The group at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center reported positive margins in 20 of 28 patients (71%) (56). Of the 20 patients with microscopically positive margins, 14 (70%) developed recurrent disease, while of the 8 patients with negative margins, 3 (38%) developed a recurrence.

Figure 13.1 Paget’s disease of the vulva. Note the weeping, eczematoid appearance, particularly posteriorly on the left, where there is early extension onto the inner thigh.

Although surgical margins may be checked with frozen sections, these can be misleading (58), and resection of the entire gross lesion with margins of at least 1 cm will control symptoms and exclude invasive disease.

The role of radiotherapy for vulvar Paget’s disease has been reviewed by Brown et al. (59). It may be most useful when the disease involves the anus or urethra, and surgery would involve diversion and stoma formation.

Another alternative approach that has been used for primary management is photodynamic therapy. An Italian study reported 32 patients who were treated with three cycles of aminolevulinic acid methyl-esther photodynamic therapy (M-ALA PDT) (60). Three patients (9.4%) had a complete resolution of symptoms and 25 (78.1%) had a partial resolution. The authors felt that M-ALA PDT was able to control large and multiple lesions regardless of the area involved, and that it preserved cosmetic and functional anatomy. However, the treatment is not curative. All patients recurred, and one progressed to invasive disease.

In general, recurrent lesions should be treated by further surgical resection, although laser therapy may occasionally be useful, particularly for perianal disease. Topical Imiquimod cream (5%) has been used successfully for patients with recurrent Paget’s disease of the vulva (61). There is no consensus on dosage or duration of use, and it has been prescribed 3 to 7 times a week, for 6 to 24 weeks.

Invasive Paget’s Disease

If an underlying invasive carcinoma is present, it should be treated in the same manner as a squamous vulvar cancer. This may require radical vulvectomy and at least an ipsilateral inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. From their literature review, Niikura et al. (53) reported positive nodes in 30% of patients (23 of 70) with Types 1b or 1c Paget’s disease of the vulva.

Lymph node metastases have been reported in patients with very superficially invasive tumors. Fine et al. reported a patient who had invasion no greater than 1 mm over a maximum length of 10 mm at her primary operation. Three weeks later, she was noted to have a palpable groin node, and at groin dissection, six positive groin nodes were resected from each groin (53). Ewing et al. (62) reported a positive sentinel node in a patient whose excised Paget’s disease had scattered foci of superficial dermal invasion to a maximum depth of 0.7 mm.

Minimally invasive Paget’s disease is rare, and in both the above cases, the surgical margins were positive for intraepithelial disease. It would seem prudent to at least monitor the groins carefully, preferably with ultrasound, if the nodes are not dissected in a patient with superficially invasive Paget’s disease.

Prognosis

A study of 1,439 patients with invasive extramammary Paget’s disease, identified from the SEER database from 1973 to 2007, reported that most (80.4%) had localized disease, 17.1% had locoregional spread, and 2.5% had distant disease (63). The 5-year disease-specific survival was 94.9% for patients with localized disease, 84.9% for those with locoregional spread, and 52.5% for those with distant metastases.

The disease is characterized by local recurrences over many years (54–56). Recurrent lesions are usually in situ, although 5 of 76 patients (6.7%) in the British registry showed progression to invasive disease between 1 and 21 years after the initial diagnosis (54). Investigators at the Norwegian Radium Hospital reported that nondiploid tumors had an increased risk of recurrence regardless of surgical radicality (64).

Invasive Vulvar Cancer

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva is predominantly a disease of postmenopausal women, with a mean age at diagnosis of approximately 65 years.

Clinical Features

Most patients present with a vulvar lump or mass, although there is often a long history of pruritus, usually associated with a vulvar dystrophy (Fig. 13.2). Less common presenting symptoms include vulvar bleeding, discharge, dysuria, or occasionally a large metastatic mass in the groin. On physical examination, the lesion is usually raised and may be fleshy, ulcerated, leukoplakic, or warty in appearance (Fig. 13.3). Warty lesions are often initially misdiagnosed as condylomata acuminata.

Most squamous carcinomas of the vulva occur on the labia majora, but the labia minora, clitoris, and perineum also may be primary sites. A study from one University Hospital in Germany reported a recent change in location of the tumor, with 37% of cases occurring between the clitoris and urethra in the 10 years up to 2007, compared to 19% in the 1980s (p < 0.05) (3). Approximately 10% of the cases are too extensive to determine a site of origin, and approximately 5% of the cases are multifocal.

As part of the clinical assessment, the groin lymph nodes should be palpated, a Papanicolaou smear taken from the cervix, and colposcopy of the cervix and vagina performed because of the common association with other squamous intraepithelial neoplasms of the lower genital tract.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis requires a wedge or a Keyes biopsy specimen, which usually can be taken in the office under local anesthesia. The biopsy must include some underlying dermis and connective tissue so that the pathologist can adequately evaluate the depth of stromal invasion. It is preferable to leave the primary lesion in situ to allow the treating surgeon to fashion adequate surgical margins.

Routes of Spread

Vulvar cancer spreads by the following routes:

1. Direct extension, to involve adjacent structures such as the vagina, urethra, and anus.

2. Lymphatic embolization to regional lymph nodes.

3. Hematogenous spread to distant sites, including the lungs, liver, and bone.

Figure 13.2 Squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva arising in a patient with long-standing lichen sclerosus. Note the butterfly distribution of the lichen sclerosus and the early invasive cancer on the left.

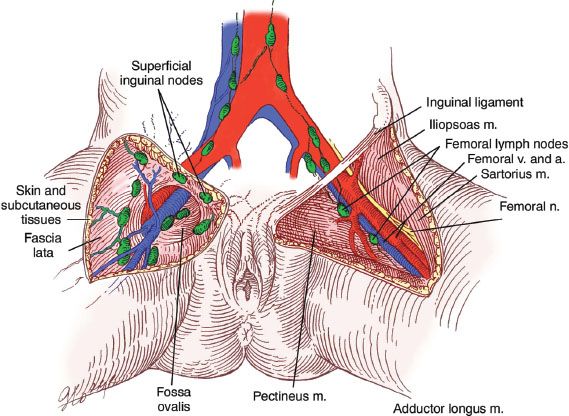

Lymphatic metastases may occur early in the disease. Initially, spread is usually to the inguinal lymph nodes, which are located between Camper’s fascia and the fascia lata. From these superficial groin nodes, the disease spreads to the femoral nodes, which are located medial to the femoral vein (Fig. 13.4). Cloquet’s node, situated beneath the inguinal ligament, is the most cephalad of the femoral node group. Metastases to the femoral nodes without involvement of the inguinal nodes have been reported (65–67). In addition, Gordinier et al. (68) reported groin recurrence in 9 of 104 patients (8.7%) treated by superficial inguinal lymphadenectomy at the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. The median number of lymph nodes removed per groin was 7, and the median time to recurrence was 22 months.

From the inguinofemoral nodes, the cancer spreads to the pelvic nodes, particularly the external iliac group. Although direct lymphatic pathways from the clitoris and Bartholin gland to the pelvic nodes have been described, these channels seem to be of minimal clinical significance (21,69).

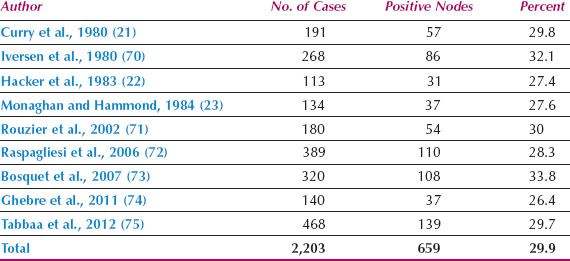

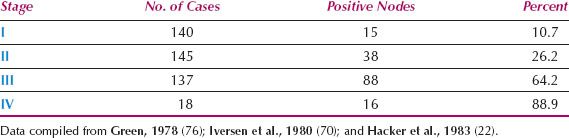

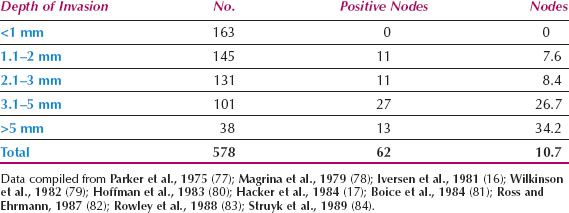

Since 1980, the overall incidence of lymph node metastases is reported to be approximately 30% (Table 13.3) (21–23,70–75). The incidence in relation to clinical stage of disease is shown in Table 13.4 (22,71,76), and in relation to depth of invasion in Table 13.5 (16,17,77–84). Data on 446 patients with primary vulvar cancer from the Mayo Clinic revealed that the incidence of lymph node metastases in relation to tumor size was as follows: 1 cm or less, 7%; 1.1 to 2 cm, 22.2%; 2.1 to 3 cm, 26.9%; and 3.1 to 5 cm, 34.1% (73).

Metastases to pelvic nodes are uncommon, the overall reported frequency being approximately 9%. About 20% of patients with positive groin nodes have positive pelvic nodes (85). Pelvic nodal metastases are rare in the absence of clinically suspicious (N2) groin nodes (22), three or more positive groin nodes (21,22,70,73) and a tumor with invasion >4 mm (73).

Figure 13.3 Exophytic squamous cell carcinoma involving the clitoris and right anterior labia.

Figure 13.4 Inguinal-femoral lymph nodes. (Reproduced from Hacker NF. Vulvar cancer. In: Hacker NF, Moore JG. Essentials of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2008, with permission.)

Table 13.3 Incidence of Lymph Node Metastases in Operable Vulvar Cancer

Hematogenous spread usually occurs late in the course of vulvar cancer and is rare in the absence of lymph node metastases. Hematogenous spread is uncommon in patients with one or two positive groin nodes, but is more common in patients with three or more positive nodes (22).

Staging

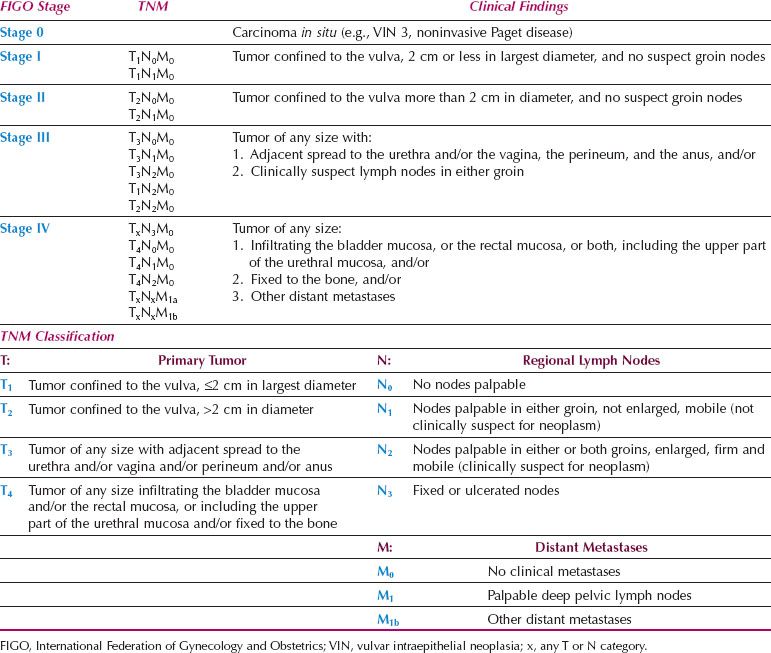

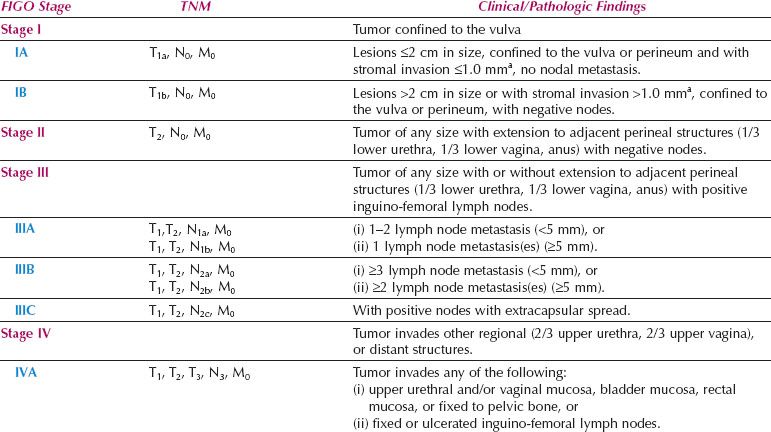

A clinical staging system based on the TNM classification was adopted by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) in 1969 (Table 13.6) (86). The staging was based on a clinical evaluation of the primary tumor and regional lymph nodes and a limited search for distant metastases.

Clinical evaluation of the groin lymph nodes is inaccurate. Bosquet et al. (73) reported that pooled data from six institutions showed that 19.5% of patients (88 of 451) with clinically negative nodes had positive nodes histologically, and 21.8% of patients (53 of 243) with clinically positive nodes had negative nodes histologically. The Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) data revealed that compared with surgical staging of vulvar cancer, the percentage of error in clinical staging increased from 18% for stage I disease to 44% for stage IV disease (87).

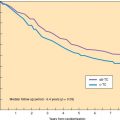

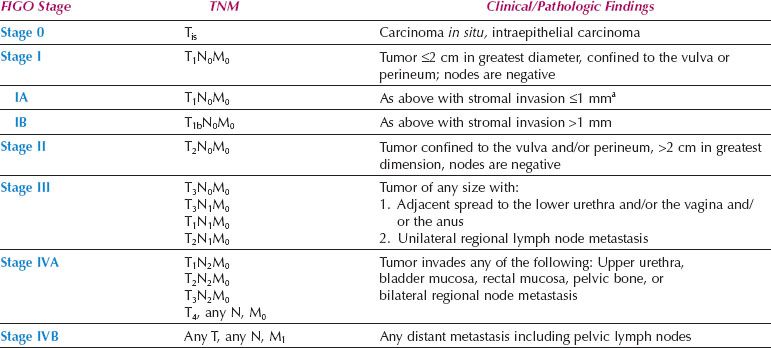

These factors led the Cancer Committee of FIGO to introduce a surgical staging for vulvar cancer in 1988. Stage I was subdivided in 1994 (Table 13.7). Although this system took the histologic status of the nodes into account, it had four major problems (88). The first was that patients with negative lymph nodes have a very good prognosis, regardless of the size of the primary tumor. Data from the Royal Hospital for Women in Sydney revealed a 96.4% 5-year survival for 121 patients with Stages I or II disease (89). The second was that stage III represented a heterogeneous group of patients prognostically, because it included patients with and without positive lymph nodes. The GOG analysis of 588 patients reported that survival for patients with stage III disease ranged from 34–100% (87). Rouzier et al. (90) reported a cohort of 895 patients with FIGO Stage III vulvar cancer who had been registered with the SEER database from 1988 through 2004. The 5-year overall survival for patients with regional metastatic nodal disease (39%) was significantly worse than that of patients with locally advanced tumors but negative nodes (62%, p < 0.0001). The third problem was that the number of positive nodes and the morphology of the positive nodes were not taken into account (21,22,87,91,92), and the final problem was that most reports indicate that bilaterality of positive nodes is not an independent prognostic factor (21,22,87,91,92).

Table 13.4 Incidence of Lymph Node Metastases in Relation to Clinical Stage of Disease

Table 13.5 Nodal Status in T1 Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vulva versus Depth of Stromal Invasion

Table 13.6 FIGO Clinical Staging of Carcinoma of the Vulva (1969)

Table 13.7 FIGO Surgical Staging for Vulvar Cancer (1994)

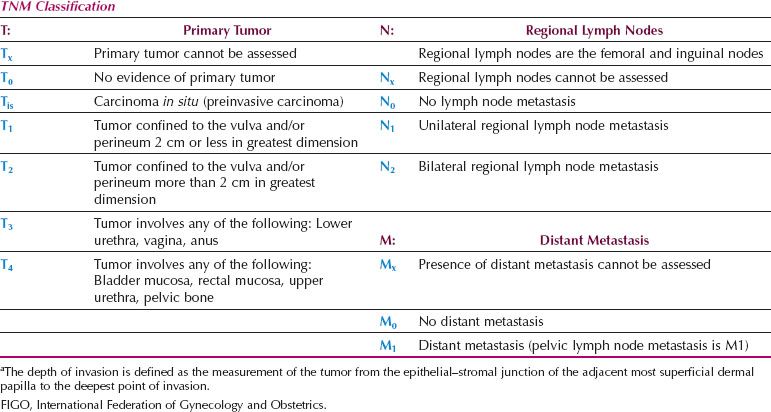

A new FIGO Staging System for Vulvar Cancer was introduced in 2009 (Table 13.8), to address the above issues. Stage IA remains unchanged, but Stages I and II have been combined. The 2009 staging system also shifted patients who have distal vaginal, distal urethral or anal involvement from the T3 to the T2 category and (if N0) from FIGO stage III to FIGO stage II. This shift classifies patients more accurately according to prognosis (which is dominated by the nodal status) but the new T2 category now includes patients who are treated with surgery alone, together with lesions that may be treated with initial radiation to preserve urethral or anal function.

Table 13.8 FIGO Surgical Staging for Vulvar Cancer (2009)

The number and morphology of positive nodes have been taken into account in Stage III, and the bilaterality of positive nodes has been discounted. Dutch workers reported that the new FIGO staging system led to a 42% downstaging, and did provide a better reflection of prognosis (93).

Treatment

After the pioneering work of Taussig (12) in the United States and Way (10,13) in Great Britain, en bloc radical vulvectomy and bilateral dissection of the groin and pelvic nodes became the standard treatment for most patients with operable vulvar cancer. If the disease involved the anus, rectovaginal septum, or proximal urethra, some type of pelvic exenteration was combined with this dissection.

Although the survival rate improved markedly with this aggressive surgical approach, several factors have led to modifications of this “standard” treatment plan during the past 25 years. These factors include earlier presentation of women in Western countries, and increasing concern among both patients and doctors about the physical and psychosexual morbidity associated with radical vulvectomy.

Modern management of vulvar cancer requires an experienced, multidisciplinary team approach, which is available only in tertiary referral centers. Successful centralization of the management of patients with vulvar occurred in the eastern part of the Netherlands following the release of national guidelines by the Dutch Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology in 2000. In the decade prior to the release of the guidelines, 62% of patients (123 of 198) were treated in an oncology center, but this increased to 93% (172 of 184) from 2000 to 2008. The 5-year relative survival improved from 69% to 75% with the centralization of care, and after adjustment for age and stage, being treated in a specialized oncology center was found to be an independent prognostic factor (94).

The shortcomings of treatment in nonreferral units were highlighted in a British study. Investigators retrospectively reviewed the records of 411 patients with squamous cell carcinoma who had been notified to the Central Intelligence Unit of the West Midlands during two 3-year periods: 1980 to 1982 and 1986 to 1988 (95). The women were treated at 35 different hospitals, 16 of which averaged 1 case or less per year. Fifteen different operations were used, the most common of which were simple vulvectomy (35%) and radical vulvectomy with bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy (34%). Hemivulvectomy was performed in only five patients (1.2%). Only 190 of the 411 patients (46%) had a lymphadenectomy performed, and a unilateral dissection was performed in only 9 patients (2.1%). Survival data for all FIGO stages compared unfavorably with the GOG data from tertiary units in the United States (87): 78% versus 98% for stage I disease; 53% versus 85% for stage II; 27% versus 74% for stage III; and 13% versus 31% for stage IV. Omission of lymphadenectomy was the single most important prognostic factor, but treatment in a hospital with less than 20 cases in total was a poor prognostic factor in univariate analysis (95).

Management of Early Vulvar Cancers

The modern approach to the management of patients with carcinoma confined to the vulva should be individualized (15,17,89,96). There is no “standard” treatment applicable to every patient, and emphasis is on performing the most conservative operation consistent with cure of the disease.

In considering the appropriate operation, it is necessary to determine independently the appropriate management of the following:

1. The primary lesion

2. The groin lymph nodes

Before any surgery, all patients should have colposcopy of the cervix, vagina, and vulva, because preinvasive (and rarely invasive) lesions may be present at other sites along the lower genital tract.

Management of the Primary Lesion

The two factors to take into account in determining the management of the primary tumor are the following:

1. The condition of the remainder of the vulva

2. The presence or absence of multifocal invasive disease

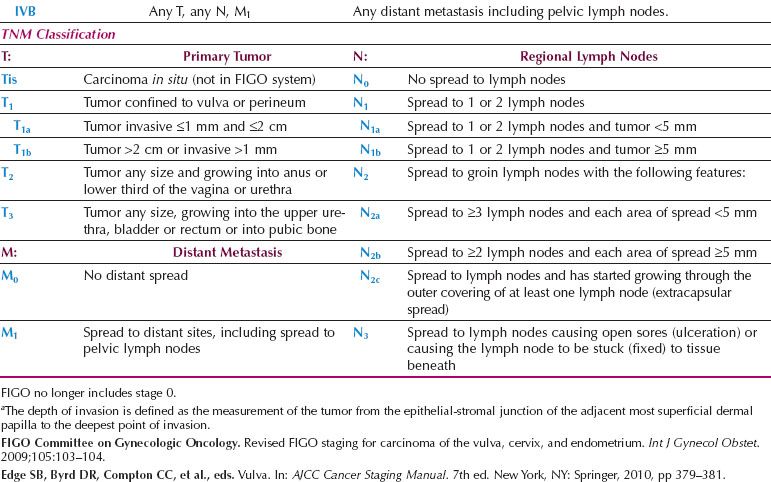

Table 13.9 Invasive Vulvar Recurrence versus Histopathologic Resection Margins

Although radical vulvectomy has been regarded as the standard treatment for the primary vulvar lesion, this operation is associated with significant disturbances of sexual function and body image. Andersen and Hacker (97) reported that, when compared with healthy adult women, sexual arousal was reduced to the eighth percentile and body image to the fourth percentile in women who had undergone vulvectomy.

Since the early 1980s, several investigators have advocated a radical local excision rather than a radical vulvectomy for the primary lesion in patients with T1 and T2 tumors (14–20,89,96,98,99). Regardless of whether a radical vulvectomy or a radical local excision is performed, the surgical margins adjacent to the tumor will be the same, and an analysis of the available literature indicates that the incidence of local invasive recurrence is low if the histopathologic margin (after fixation) is at least 8 mm (Table 13.9) (89,99–101). Allowing for 20% tissue shrinkage with formalin fixation, this translates to a surgical margin of at least 1 cm.

When vulvar cancer arises in the presence of VIN or some nonneoplastic epithelial disorder, radical local excision should be performed for the invasive disease, and the associated disease should be treated in the most appropriate manner. For example, topical steroids may be required for squamous hyperplasia or lichen sclerosus, whereas VIN should be treated by superficial local excision and primary closure or split thickness skin grafting.

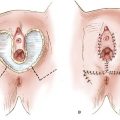

Radical local excision of the invasive lesion is most appropriate for lesions on the lateral or posterior aspects of the vulva (Fig. 13.5), where preservation of the clitoris is feasible. For patients with anterior lesions, surgical resection that includes clitorectomy can have serious psychosexual consequences, particularly in younger patients. Chan et al. (102) identified 41 patients with squamous carcinoma of the anterior vulva not involving the clitoris. Thirteen patients (32%) had clitoral sparing modified radical vulvectomy and 28 (68%) had radical vulvectomy. The 13 patients who had clitoral sparing surgery included 8 with stage I, two with stage II, two with stage III, and one with stage IV disease. After a median follow-up of 59 months, none of the 13 patients having conservative surgery had locoregional failure.

In young patients with actual involvement of the clitoris or in whom surgical margins would be <5 mm, consideration should be given to treating the primary lesion with a small field of radiation therapy. Small vulvar lesions can often be controlled with 60 to 64 Gy of external radiation, typically using an appositional electron field; if there is suspicion of persistent disease, biopsy can be performed after therapy to confirm complete response (103).

Local Control Rates after Surgical Management of Early Lesions

Two recent papers have looked at single institutional experiences with T1 and T2 squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (89,96).

In the study from Kentucky, 61 patients with a lateral T1 lesion and 61 patients with a lateral T2 lesion were seen from 1963 to 2003 (96). Radical vulvectomy was performed on 60 patients (49%) and radical hemivulvectomy on 62 (51%). Ipsilateral inguinal node metastases were present in 11% of patients (7 of 61) with a T1 lesion, and 31% (19 of 61) of patients with a T2 lesion. Disease-free survival of patients with T1 and T2 lesions was 98% and 93%, respectively at 5 years. Local or distant recurrence was not more common in patients treated by radical vulvectomy or radical hemivulvectomy.

Figure 13.5 Small (T1) vulvar carcinoma at the posterior fourchette. Note that the remainder of the vulva is normal.

The 49% incidence of radical vulvectomy in this study is not surprising, because the study dates back to 1963, which is about 20 years before radical local excision was being advocated. More concerning is a 2008 SEER study of 523 patients, which reported that 46–54% of patients with vulvar cancer in the United States still underwent a radical or total vulvectomy (104).

Our experience at the Royal Hospital for Women in Sydney suggests that radical vulvectomy is rarely necessary. Of 121 patients with 1994 FIGO stages I and II vulvar cancer managed from 1987 through 2005, radical local excision was performed in 116 patients (95.9%) (89). Only five patients (4.1%) underwent radical vulvectomy, in all cases for tumor multifocality. With a median follow-up of 84 months, the overall survival at 5 years was 96.4%.

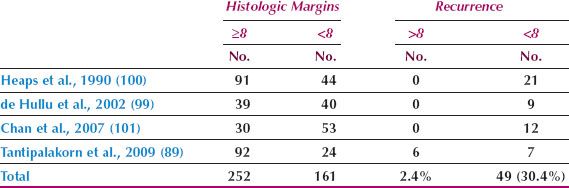

Technique for Radical Local Excision

Radical local excision implies a wide and deep excision of the primary tumor. An elliptical incision should be drawn using a marking pen, with the skin in its natural position. Surgical margins around the tumor should be at least 1 cm. The incision should be carried down to the inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm, which is coplanar with the fascia lata and the fascia over the pubic symphysis. The surgical defect is closed in two layers. For perineal lesions, proximity to the anus may preclude adequate surgical margins, and consideration should be given to preoperative or postoperative radiation in such cases. For periurethral lesions, the distal half of the urethra may be resected without loss of continence. Figure 13.6 shows the satisfactory cosmetic result achieved in the treatment of the lesion shown in Figure 13.5.

Management of the Groin Lymph Nodes

Appropriate management of the regional lymph nodes is the single most important factor in decreasing the mortality from early vulvar cancer. With respect to lymph node metastases, two facts are apparent:

1. The only patients without significant risk of lymph node metastases are those with a tumor up to 2 cm in diameter, that invades the stroma to a depth no greater than 1 mm (Table 13.5).

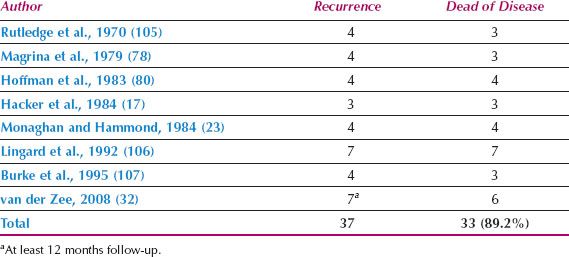

2. Patients in whom recurrent disease develops in an undissected groin have a very high mortality rate (Table 13.10) (17,23,32,78,80,105–107).

Figure 13.6 Satisfactory cosmetic result after radical local excision and bilateral groin dissection (for the small posterior vulvar carcinoma shown in Fig. 13.2).

The safest treatment for all patients with a 2 cm tumor with more than 1 mm of stromal invasion, and all patients with a tumor greater than 2 cm in diameter, is inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. A wedge or Keyes biopsy of the primary tumor should be obtained, and the depth of invasion determined. If it is less than 1 mm on the biopsy specimen, and the lesion is 2 cm or less in diameter, the entire lesion should be locally excised and serially sectioned to determine the depth of invasion. If there is still no invasive focus deeper than 1 mm, groin dissection may be omitted. Although there have been case reports positive nodes in a patient with Stage 1A vulvar cancer (108,109), the incidence is extremely low.

Table 13.10 Death from Recurrence in an Undissected Groin

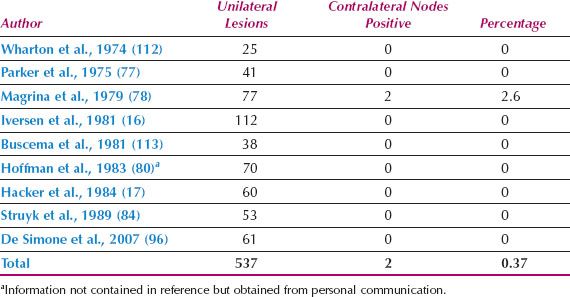

Table 13.11 Incidence of Positive Contralateral Nodes in Patients with Lateral T1 Squamous Carcinomas

If groin dissection is indicated in patients with early vulvar cancer, it should be a thorough inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (110). The GOG reported six groin recurrences among 121 patients with T1N0 or N1 tumors after a superficial (inguinal) dissection, even though the inguinal nodes were reported as negative (111). This large, multi-institutional study indicates that modification of the groin dissection increases groin recurrences and, therefore, mortality.

It is not necessary to perform a bilateral groin dissection if the primary lesion is unilateral (defined as 2 cm or more from the midline) and the ipsilateral nodes are negative (Table 13.11) (16,17,77,78,80,84,96,112,113).

Retrospective analysis of a GOG study investigating sentinel lymph node localization before definitive groin dissection was undertaken to determine the safety of unilateral dissection in patients with near midline lesions (114). Sixty-five patients had lesions within 2 cm of the midline, and all underwent bilateral groin dissection. Bilateral drainage was identified in 58% of cases (38 of 65). No nodal metastases were found in the contralateral groin in the 27 patients with ipsilateral drainage identified at lymphatic mapping.

Lesions involving the anterior labia minora should have bilateral dissection because of the more frequent contralateral lymph flow from this region (115).

Measurement of Depth of Invasion

The Nomenclature Committee of the International Society of Gynecologic Pathologists has recommended that depth of invasion be measured from the most superficial dermal papilla adjacent to the tumor to the deepest focus of invasion. This method was originally proposed by Wilkinson et al. (79). Tumor thickness is also commonly measured (77,116), and Fu (117) estimated that the average difference between tumor thickness and depth of invasion as determined by the Wilkinson method was 0.3 mm.

Technique for Groin Dissection

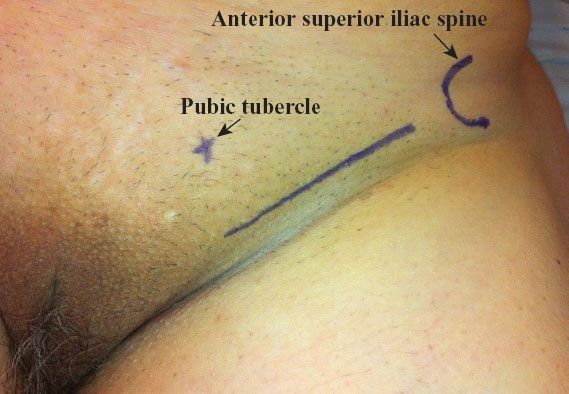

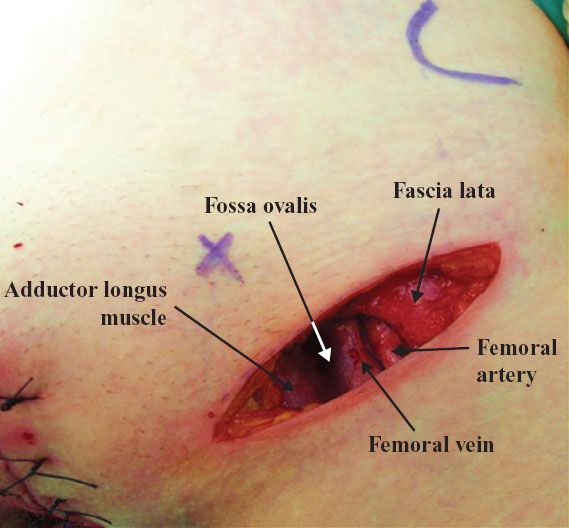

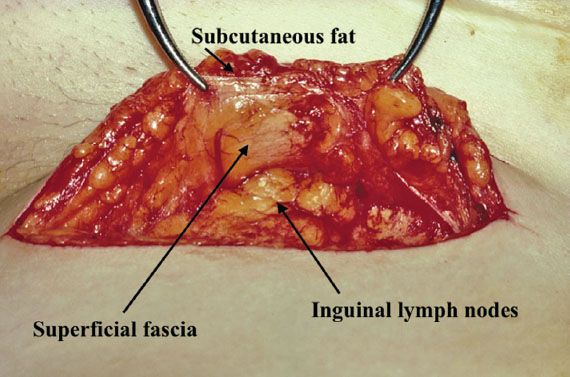

A linear incision is made 1 cm above and parallel to the groin crease along the medial three quarters of a line drawn between the anterior superior iliac spine and labiocrural fold (Fig. 13.7). This incision will be directly over the fossa ovalis (Fig. 13.8). Studies of bipedal lymphangiograms have demonstrated that there are no lymph nodes adjacent to the anterior superior iliac spine (118). On the basis of embryologic and anatomical studies, Micheletti et al. (119) have proposed that the superficial circumflex iliac vessels could represent the lateral surgical landmark. The incision is carried through the subcutaneous tissues to the superficial (Camper’s) fascia. This layer can be definitively identified, because the superficial circumflex iliac and superficial external pudental veins run immediately below it. The superficial fascia is incised and grasped with artery forceps to place it on traction, and the fatty tissue between it and the fascia lata is removed over the femoral triangle (Fig. 13.9). To avoid skin necrosis, all subcutaneous tissue above Camper fascia must be preserved. The dissection is carried 1 cm above the inguinal ligament to include all the inguinal nodes.

Figure 13.7 Skin incision for groin dissection through a separate incision. The incision is made 1 cm above the groin crease along the medial three quarters of a line drawn between the anterior superior iliac spine and the labiocrural fold.

The saphenous vein is usually tied off at the apex of the femoral triangle and at its point of entry into the femoral vein. Some authors have suggested that saphenous vein sparing may decrease postoperative morbidity (120,121), although in a study of 64 patients, 31 of whom underwent saphenous sparing, Zhang et al. (121) reported no difference in the incidence of postoperative fever, acute cellulitis, seroma, or lymphocyst formation.

The fatty tissue containing the femoral lymph nodes is removed from within the fossa ovalis. There are only one to three femoral lymph nodes, and they are always situated medial to the femoral vein in the opening of the fossa ovalis (122). Hence, there is no need to remove the fascia lata lateral to the femoral vessels. Cloquet’s node is not consistently present but should be checked for by retraction of the inguinal ligament cephalad over the femoral canal. The wound is closed in two layers, tacking the superficial fascia to the deep fascia. The author no longer places a drain in the groin.

Postoperative Management

In spite of the age and general medical condition of most patients with vulvar cancer, the surgery is usually remarkably well tolerated. However, a postoperative mortality rate of about 1% can be expected, usually as a result of pulmonary embolism or myocardial infarction. A low-residue diet may be commenced on the first postoperative day, and bed rest is advisable for 2 to 3 days to allow immobilization of the wounds to foster healing. Pneumatic calf compression and subcutaneous heparin or clexane should be used to help prevent deep venous thrombosis, and active, nonweight-bearing leg movements should be encouraged. Perineal swabs should be given until the patient is fully mobilized, at which stage sitz baths or whirlpool therapy is helpful. A Foley catheter is usually left in the bladder until the patient is ambulatory.

Figure 13.8 Groin incision is directly over the fossa ovalis.

Figure 13.9 Camper fascia kept on traction with forceps while the underlying node-bearing fatty tissue is dissected out of the femoral triangle. Note the preservation of the subcutaneous tissue above the superficial fascia. This ensures that skin necrosis will not occur.

Early Postoperative Complications

The major immediate morbidity is related to the groin dissection. With the separate incision approach, and sparing of all subcutaneous fat above the superficial fascia, the incidence of wound breakdown is very low, patients mainly at risk being heavy smokers and diabetics. The most common problem is lymphocyst formation, which occurs in about 40% of cases (123). These seem to have become more common since introducing the practice of leaving the fascia lata over the muscles in the floor of the femoral triangle. If large, lymphocysts are best managed by making a linear incision 1 to 2 cm long, and inserting a corrugated drain until the skin flaps have adhered to the underlying tissues. Early mobilization and long walks before the groin is completely healed seem to increase the incidence of lymphocysts.

Other early postoperative complications include cellulitis, urinary tract infection, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, hemorrhage, and, rarely, osteitis pubis.

Late Complications

The major late complication is chronic leg edema, which has been reported in up to 69% of patients (91). At the Royal Hospital for Women in Sydney, the self-reported incidence of lymphedema after groin dissection was 62% (124). In about 50% of patients, the onset of lymphedema occurred within 3 months, while about 85% experienced the onset within 12 months. Lymphedema was significantly related to the occurrence of early complications, particularly cellulitis (124).

Recurrent lymphangitis or cellulitis of the leg occurs in about 10% of patients. It can develop very quickly, and may need hospitalization and intravenous antibiotics. Urinary stress incontinence, with or without genital prolapse, occurs in about 10% of patients and may require corrective surgery. Introital stenosis can lead to dyspareunia and may require a vertical relaxing incision, which is sutured transversely. An uncommon late complication is femoral hernia, which can usually be prevented during surgery by closure of the femoral canal with a suture from the inguinal ligament to Cooper ligament. Pubic osteomyelitis and rectovaginal or rectoperineal fistulae are rare late complications.

Lymphatic Mapping

The major morbidity associated with the modern management of vulvar cancer is chronic lower limb lymphedema, which occurs in about 60% of patients following groin dissection, and is a lifelong affliction. Hence, for the last 30 years, there has been much interest in eliminating or modifying the groin dissection for patients with negative nodes.

Several noninvasive methods for detecting lymph node metastases have been disappointing, including positron emission tomography (125), computerized tomographic scanning (126), and magnetic resonance imaging (127). Ultrasonic scanning, particularly when combined with fine needle aspiration cytology, shows more promise, but false negatives and false positives still occur (126,128).

For the past decade or more, researchers have been investigating the feasibility of using sentinel node identification to avoid complete inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy in selected patients with vulvar cancer. This concept was initially introduced by Cabanas (129) for the management of men with penile cancer in 1977, and subsequently pioneered for the management of melanomas by Morton et al. (130) in 1992. The hypothesis is that if the sentinel node is negative, all other nodes will be negative, so the patient can be spared the morbidity of full groin dissection.

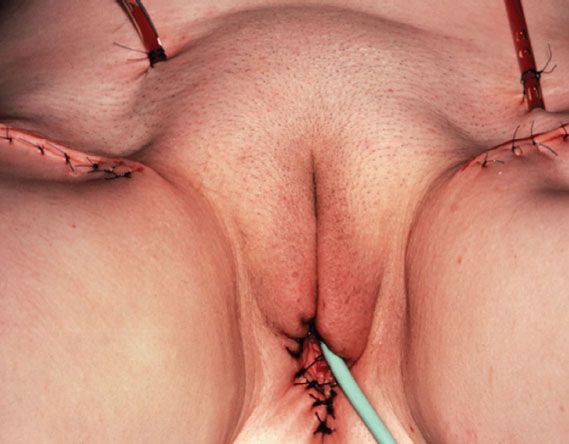

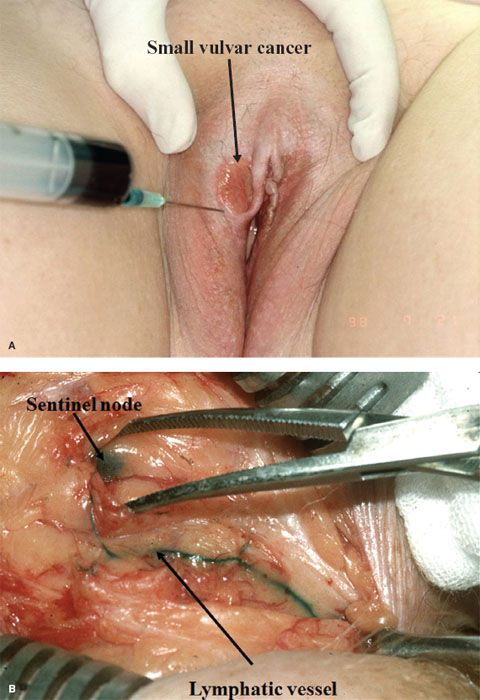

The sentinel node (or nodes) is identified by the injection of intradermal isosulfan blue dye around the primary vulvar lesion, in combination with intradermal radioactive 99mTc-labeled sulfur colloid (32,131,132). After the injections, the node(s) is isolated in the groin by dissection (to identify the blue node or nodes) (Fig. 13.10) and gamma counting. Ultrastaging, using serial sectioning and immunoperoxidase staining for cytokeratin, is undertaken if the sentinel node is negative on routine hematoxalin and eosin staining.

In the past 5 years, three large national groups have reported their results on the use of sentinel node identification to obviate the need for groin dissection in patients with early vulvar cancer (32, 131,132).

Figure 13.10 Lymphaticmapping utilizing an intradermal injection of blue dye immediately preoperatively (A). Note the blue lymphatic vessel and blue sentinel node at groin dissection (B).

The Groningen multicenter observational study, which was published in 2008, used both radiotracer and blue dye (32). Eligible patients were those with squamous cell carcinomas <4 cm diameter. If the sentinel node was negative on ultrastaging, groin dissection was omitted and the patient was observed clinically every 2 months for 2 years. From March 2000 to June 2006, 403 assessable patients were recruited to the study, and they underwent 623 groin dissections. Metastatic sentinel nodes were found in 163 groins (26.2%). Routine pathologic examination detected 95 (58.3%) cases and ultrastaging detected a further 68 (41.7%). In eight of 276 patients in the observational study, groin recurrence was observed after a negative sentinel node procedure. The actuarial groin recurrence rate after 2 years was 3% (95%, CI 1–6%). All patients with a groin recurrence underwent bilateral inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy and adjuvant (chemo)radiation. Six of the eight patients died of disease, while two remained disease-free at 6 and 50 months after recurrence. The median time to recurrence was 12 months (range 5 to 16 months). As expected, both short-term and long-term morbidity were significantly decreased in patients undergoing sentinel node biopsy only.

The results of the multicenter German study were also published in 2008 (131). Between 2003 and 2006, 127 women with T1–T3 vulvar cancer were entered onto the study. Radiotracer and blue dye were used in 72 patients (56.6%), radiotracer alone in 47 (37%), and blue dye alone in 8 (6.3%). In two cases (1.6%), no sentinel nodes were detected. All patients underwent complete inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. Positive nodes were identified in 39 cases (30.7%) at groin dissection, but three patients had a negative sentinel node, giving a false-negative rate of 7.7%. In one additional midline tumor, the sentinel node was positive on one side, but falsely negative on the other, so the actual false-negative rate for this study should be 10.3%.

The GOG study was published in 2012 (132). Between 1999 and 2009, 452 eligible patients with squamous carcinomas 2 to 6 cm diameter were recruited. None had clinically suspicious groin nodes, and all underwent complete inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. Blue dye was used for all patients, and radiotracer was mandated 2 years after study activation. The incidence of positive groin nodes among women with at least one sentinel node identified was 31.6% (132 of 418) and the false-negative rate was 8.3% (11 of 132).

A single institution study from Poland highlights the need to continue to utilize sentinel node biopsy within a research protocol (133). Fifty-six patients with squamous cell carcinomas of the vulva 4 cm or less in diameter underwent sentinel node detection with radiotracer and blue dye, and 109 inguinofemoral lymphadenectomies were performed. Sentinel nodes were identified in 76% of patients with blue dye (82 of 108), and 99% with the radiotracer (106 of 107) (p < 0.0001). Positive sentinel nodes were found in 17% of groins (19 of 109), and there were 7 false-negative sentinel nodes, giving a false-negative rate of 27%. The authors concluded that in their setting, they could not recommend sentinel node biopsy as a reliable alternative to complete groin dissection. They felt that it was likely that “the main factor responsible for the high false-negative rate was the surgeon’s experience. Although all the operations were performed by surgeons with at least 15 years’ experience, the procedure was performed only a few times by each surgeon.” This highlights the problem of introducing a technically challenging procedure for an uncommon disease.

If a sentinel node is positive, additional groin treatment is mandatory. In a review of the Groningen study, investigators reported that there was no cutoff in the size of the metastatic focus in the sentinel node below which the chances of nonsentinel node metastases were close to zero (134).

Sentinel node biopsy is considered to be standard practice in patients with early breast cancer, and in spite of false-negative rates of around 10%, isolated axillary failures are rare. This is because the majority of node-negative patients with breast cancer receive some type of adjuvant therapy that can effectively treat any micrometastases (135). This is not true for patients with vulvar cancer, where adjuvant radiation is not given to patients with negative nodes.

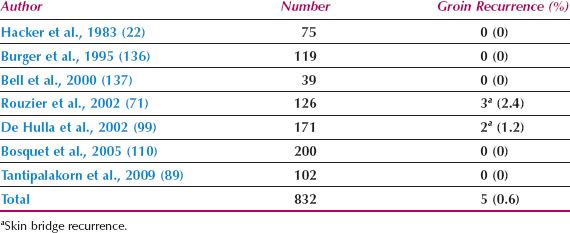

Recurrence in a groin following inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy and negative nodes is rare (Table 13.12) (22,71,89,99,110,136,137) but all attempts at modified groin dissection, including superficial inguinal dissection, have resulted in a groin recurrence rate of about 5% (Table 13.13) (68,96,107,110,111,138–140). The false-negative rate for vulvar sentinel node biopsy ranges from 3–27% (131–133), and in the hands of the average operator, is likely to be at least 7–10% (131,132). About 80–90% of patients who develop a recurrence in an undissected groin will die from their disease, so while sentinel node biopsy will decrease the incidence of lymphedema, it is also important for the patient to be aware of the rate and consequences of a false-negative result. Hence, properly informed consent is crucial.

Three studies have evaluated patient preferences in this regard. Firstly, de Hullu et al. (141) sent structured questionnaires both to patients who had been treated for vulvar cancer and to gynecologists. The response rate among patients was 91% (107 of 118). Sixty percent of the patients preferred complete lymphadenectomy in preference to a 5% false-negative rate of the sentinel node procedure. Their preference was not related to age or the side effects they had experienced. The response among gynecologists was 80% (80 of 100), of whom 60% were willing to accept a 5–20% false-negative rate for the sentinel node procedure. The authors concluded that although gynecologists may consider this a promising approach, the majority of vulvar cancer patients would not advise its introduction, because they were not prepared to take any risk of missing a lymph node metastasis.

Table 13.12 Groin Recurrence Rate in Patients with Negative Nodes at Inguinofemoral Lymphadenectomy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree