(1)

State University of New York at Buffalo Kaleida Health, Buffalo, NY, USA

For large tumors in the neck, wide margins often cannot be obtained because of the multiplicity and importance of anatomical structures. For most patients, however, it should be possible to follow removal of the gross tumor with adjuvant modalities such as radiation if the margins are considered inadequate. The illustrations in this chapter show a patient with a mass in the left lower neck and may serve as a model for the removal of tumor masses located in this area.

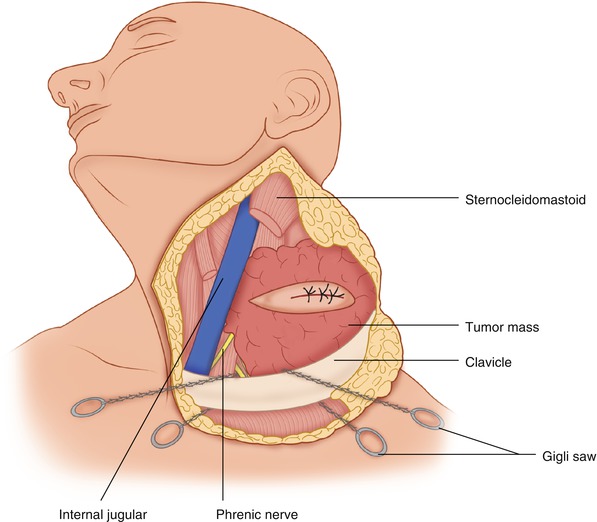

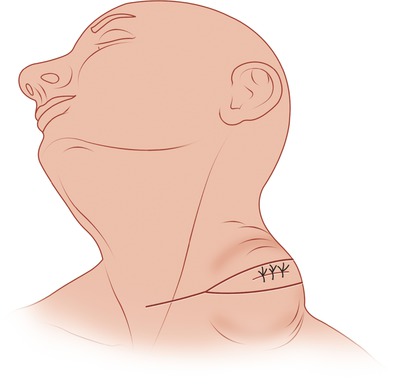

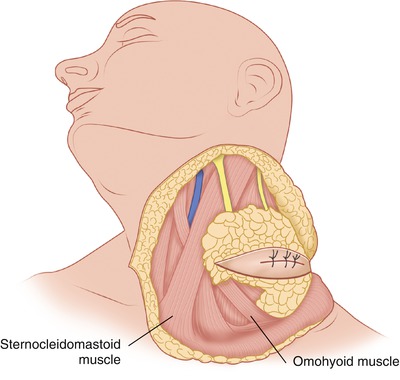

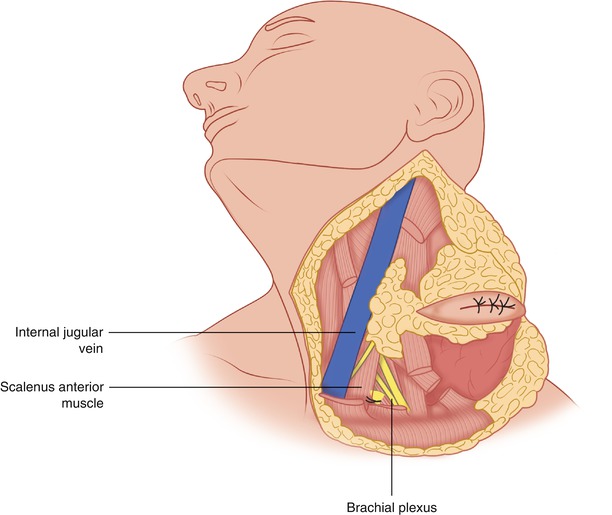

A transverse elliptical incision is carried out to circumscribe the previous biopsy incision (Fig. 14.1). Skin flaps are raised superiorly and inferiorly, maintaining a plane deep to the platysma muscle if that is possible while at the same time maintaining an adequate margin around the tumor mass. Otherwise the dissection may be carried out superficial to the platysma. Both superior and inferior flaps are raised well beyond the palpable extent of the tumor. Anteriorly, the sternocleidomastoid muscle is exposed above and below the area of involvement by the tumor. The external jugular vein is encountered both superiorly and inferiorly, and it is ligated and divided at both sites. The sternocleidomastoid muscle is exposed (Fig. 14.2). The latter is divided close to its sternoclavicular origin, as well at its insertion to the mastoid process. The internal jugular vein is exposed, and if necessary, it is divided below as well as above the area occupied by the tumor. The scalenus anterior muscle is exposed medially, along with the phrenic nerve as it crosses from the lateral to the medial side of this muscle. Occasionally an accessory phrenic nerve is also present. The omohyoid muscle is divided above the clavicle and medial to the sternocleidomastoid (Fig. 14.3).

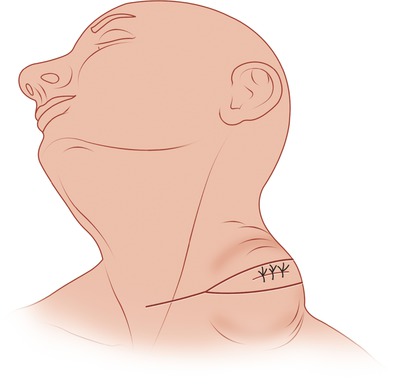

Fig. 14.1

This transverse elliptical incision includes the previous biopsy site

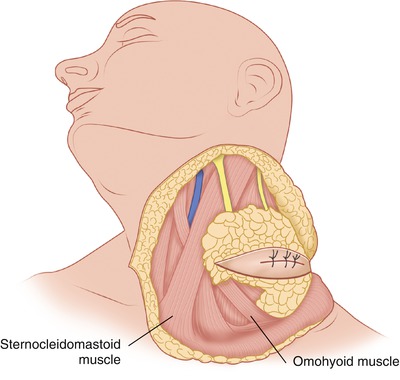

Fig. 14.2

Superior and inferior flaps are raised, exposing the sternocleidomastoid muscle anteriorly

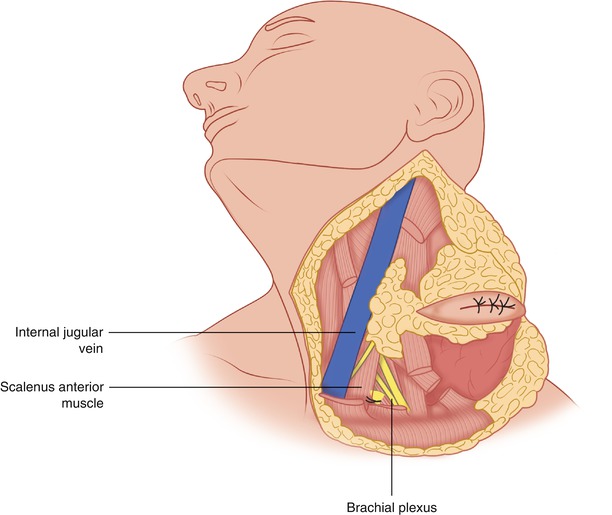

Fig. 14.3

The sternocleidomastoid muscle has been divided proximally and distally and mobilized toward the tumor. The omohyoid has been divided similarly. The internal jugular vein is exposed

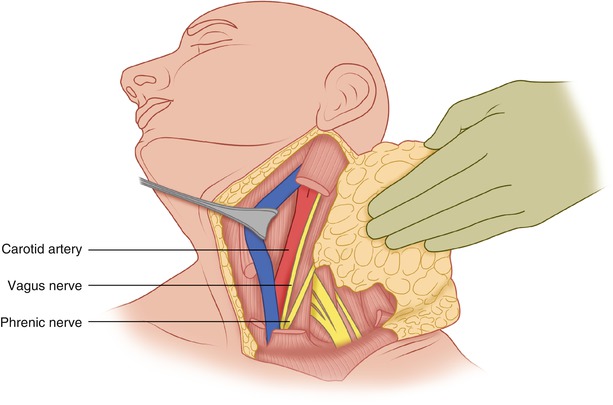

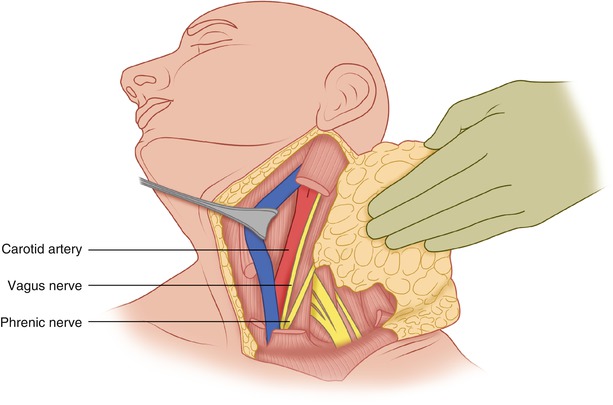

Between the carotid artery, which is now clearly visualized, and the internal jugular vein, the vagus nerve is also exposed and preserved (Fig. 14.4). General surgeons regard the vagus nerve as one that can be sacrificed with near impunity, which is true in its thoracic and abdominal portions. It is important to remember, however, that the recurrent laryngeal nerve is a branch of the vagus given off as the vagus enters the superior mediastinum. The lymph nodes from the area of the junction of the internal jugular and subclavian veins are mobilized toward the tumor as needed in order to obtain an adequate margin around the tumor mass and also to ascertain their histologic status if the tumor is likely to metastasize to adjacent lymph nodes.

Fig. 14.4

The internal jugular vein is retracted, exposing the carotid artery. The vagus and phrenic nerves and the brachial plexus are visible

In the corner of the jugular and subclavian veins, particular care should be taken to identify the thoracic duct, or at least to recognize if it is injured, so that it can be suture-ligated to avoid a protracted chylous leak. Such a postoperative leak, if excessive, can cause problems for the patient with nutritional depletion and delayed wound healing.

Lateral to the scalenus anterior muscle, at the lower part of the operative field, the superior trunk of the brachial plexus becomes visible. Dissection is carried out on the surface of the exposed trunks in order to separate them from the tumor (Figs. 14.3 and 14.4). Within a short distance, the trunks of the brachial plexus disappear underneath the clavicle, en route to occupying their position in the subclavian space and in the axillary area posterior to the pectoralis major and pectoralis minor muscles.

Occasionally, a tumor in the lower neck may extend behind the clavicle, at least partially, so that it becomes impossible to safely dissect around the lower border of the tumor without removing a part of the clavicle. There should be no hesitation in doing this, because removal of the clavicle does not entail any long-term disability. To do so, the lower flap is developed to below the lower border of the clavicle on top of the pectoralis major, and the clavicular origin of the pectoralis major muscle is divided, exposing the lower border of the clavicle. A right angle clamp is passed around the clavicle, both medial as well as lateral to the site of possible involvement or proximity of this bone to the tumor mass. A Gigli saw then is passed around the bone, which is divided both medially and laterally (Fig. 14.5). The portion of the clavicle between the two sites of its division is left in place to be removed with the underlying tumor mass. The division of the pectoralis major off its clavicular origin allows access and exposure of the axilla at level III, exposing thus the axillary vein and artery and the brachial plexus, so that there is no risk of injury to these structures. In practice, instead of simply dividing the clavicle medially and laterally, a 1- to 2-cm segment of the bone is removed medially and laterally to allow room to perform surgical maneuvers (essentially to divide the subclavius muscle medially and laterally). This muscle arising from the anterior end of the first rib, inserts in the lower surface of the lateral end of the clavicle. The tumor behind the clavicle is thus mobilized and retracted cephalad in order to continue the posterior neck dissection (Fig. 14.6).