- Various skin conditions are associated with diabetes, either type 1 or type 2, the specific chronic complications of the disease, the use of antidiabetic drugs and certain endocrine and metabolic disorders that cause diabetes.

- Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum is unrelated to glycemic control. Treatment is difficult, but in the early stages topical steroids may be beneficial.

- Diabetic dermopathy (“shin spots”) is the most common skin disorder in patients with diabetes, usually in the pre-tibial region in longstanding diabetes, and tends to resolve within 1–2 years.

- The skin is thickened in diabetes, and irreversible glycation of skin collagen and other proteins may lead ultimately to yellowish skin discoloration especially in the palmar creases.

- Acanthosis nigricans is the presence of hyperpigmented velvety hyperkeratotic plaques in the flexural regions, particularly the axillae or posterior neck. It is associated with various causes of insulin resistance.

- Erythema occurs on the face, around the nail margins and on the lower limbs.

- Calciphylaxis implies advanced vascular damage with a poor prognosis.

- Large vessel injury can lead to recalcitrant leg ulcers.

- Candidal overgrowth is frequently observed in people with poorly controlled diabetes.

- Bacterial infections such as “malignant” otitis externa can be potentially lethal.

- Erythrasma, caused by corynebacteria, is seen more frequently in obese people with diabetes.

- Dermatophytosis is not found more frequently in those with diabetes than in those without the disease.

- Vitiligo shares an autoimmune pathogenesis, like type 1 diabetes.

- There is no scientific basis for the assumption that pruritus occurs more commonly in those with diabetes.

- Necrolytic migratory erythema is an unusual rash that is diagnostic of the glucagonoma syndrome.

- Insulin injections can cause both lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy.

- Allergic insulin reactions, which are now rare because of purer insulin availability, can be subdivided into immediate-l ocal, general, delayed or biphasic responses.

- Sulfonlyureas are well-recognized causes of multiple cutaneous drug reactions.

Introduction

Various skin disorders are associated with diabetes. Some are relatively specific “markers” of the condition, usually caused by the metabolic changes in diabetes or associated with endocrine disorders that cause diabetes. Other skin conditions develop as manifestations of chronic diabetic complications, particularly vascular changes and peripheral neuropathy. Skin infections are more common in people with poorly controlled diabetes, but not specific for the condition. Cutaneous side effects of drug treatments for diabetes may occur, although these are less common with current therapies.

Cutaneous metabolic manifestations

This group includes a number of conditions that appear specific to diabetes (e.g. diabetic thick skin) or are much more common in people with diabetes than the general population (e.g. necrobiosis lipoidica). The cause of many of these conditions remain obscure, although some may be related to the process of non-enzymatic glycation of cutaneous structural proteins, particularly collagens or changes in microvascular structural proteins. A number of cutaneous conditions were previously thought to have an increased incidence in diabetes, but subsequent studies have not substantiated these links (e.g. generalized pruritus) [1]. Likewise, the evidence that granuloma annulare is associated with diabetes is inconclusive [2]. The metabolic manifestations currently regarded as being genuinely associated with diabetes are shown in Table 47.1.

Table 47.1 Cutaneous metabolic manifestations.

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum Diabetic dermopathy (“shin spots”) Diabetic bullae (bullosis diabeticorum) Diabetic thick skin:

|

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum

This is a rare condition with a prevalence of 0.3% in diabetic populations [3]. Although it is much more common in those with diabetes than individuals without diabetes, the relationship to diabetes and the etiology of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) remains unclear. An early and much quoted study of 171 patients suggested that about two-thirds of patients with NLD had diabetes, usually type 1 (T1DM) [3], with a further 12–15% having an abnormal glucose tolerance test [4]; however, patient selection may have given an overestimate of the incidence. A more recent retrospective study of 65 patients with NLD in a dermatology clinic found that 11% were known to have diabetes and a further 11% had an abnormal glucose tolerance test [5]. NLD usually develops in young adult or early middle life, but has occasionally been reported in childhood [6]. Women are three times more commonly affected than men.

There is no proven association with glycemic control, but patients with diabetes and NLD do appear to have a higher incidence of chronic diabetic complications such as retinopathy, neuropathy and microalbuminurua [7,8]. This suggests that microangiopathy may have an etiologic role. The presence of immunologic deposits in lesional vessel walls also implicates immune factors in the pathogenesis [9]. Nevertheless, the cause remains unknown.

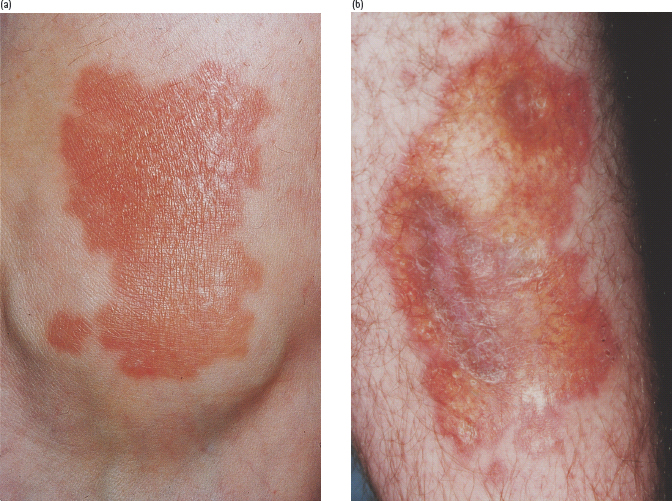

NLD has a distinctive appearance (Figure 47.1). Early lesions may be rounded, dull red, symptomless papules or plaques which slowly progress to the typical chronic lesion – an oval or irregularly shaped, indurated plaque with central atrophy [3,8]. NLD often has a shiny surface, with prominent telangiectatic vessels crossing over a waxy yellowish central area. The margin of lesions may be brownish or red and sometimes with comedo-like plugs, where necrotic material is extruded through the surface. The shin is the most commonly affected site, but the thighs, ankles and feet may also be affected; lesions rarely occur on the trunk, upper limbs or scalp [10]. Ulceration occurs in 25% of cases and may be very slow to heal. NLD lesions are usually partially or completely anesthetic and alopecia is frequently present [11]. They are variable in number but usually few and most extend slowly over several years, sometimes coalescing with adjacent areas. Long periods of quiescence may occur or occasionally NLD lesions may heal with scarring. The condition can lead to significant morbidity and cosmetic disfigurement. The diagnosis is usually clinical; a diagnostic skin biopsy is not normally required and may heal slowly or risk ulceration in atrophic lesions. The differential diagnosis of early lesions includes granuloma annulare, cutaneous sarcoid, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma and diabetic dermopathy.

Figure 47.1 Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD). (a) An early lesion on ankle showing the erythematous stage. (b) A long-standing area of NLD, note the typical yellow atrophic appearance with telangiectasia.

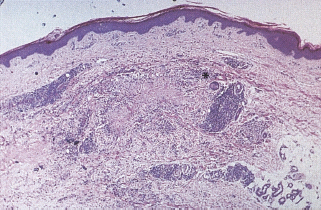

Histologically, NLD lesions consist of foci of degenerate collagen bundles with a hyalinized appearance (necrobiosis), surrounded by fibrosis, a diffuse infiltrate of histiocytes and frequently a palisading granulomatous reaction with giant cells similar to those seen in sarcoidosis (Figure 47.2). There is a superficial and deep perivascular infiltrate that is composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells [12,13]. Capillary wall thickening and microvascular occlusion are present, but do not appear central to the pathologic process. These abnormalities occur throughout the dermis. There is considerable overlap between these features and those of granuloma annulare [13], and this similarity undoubtedly contributes to the suggestion that granuloma annulare is associated with diabetes. Despite histologic similarities in the earlier stages of the two conditions they run a very different clinical course and the association has now been discounted [12,14].

Figure 47.2 Histologic feature of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum showing degeneration of the collagen (necrobiosis), associated with fibrosis and a granulomatous histiocytic infiltrate. A giant cell is indicated by an asterisk. Hematoxylin and eosin stain x40.

No treatment for NLD has proved effective in double-blind placebo controlled trials and treatment remains unsatisfactory. Spontaneous remission is unusual [3] and good diabetic control does not usually have a significant effect on the course of the condition. Patients should be encouraged not to smoke and to avoid trauma to the area which may result in a painful and recalcitrant ulcer. For early NLD lesions corticosteroids either applied topically (perhaps under occlusion) or by intralesional injection may be beneficial [15,16]. There is evidence that the inflammatory process extends beyond the clinical margins and topical steroids may halt or slow progression if applied to the periphery of lesions [8]. Once atrophy has developed this is irreversible and topical steroids should not be used in chronic lesions because they may worsen skin atrophy. There is a suggestion that topical retinoids may be beneficial in atrophic cases [17]. Oral steroids may be of benefit in a short course of 5 weeks with reduction of disease activity, but not atrophy [18]. Benefit was maintained in a 7-month follow-up but careful monitoring of blood glucose control is essential. The thiazolidinediones or glitazones have been reported to benefit NLD but more experience is required [19]. Various anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents have been tried; including aspirin, dipyridamole, heparin and oxpentifylline, but controlled trials has not shown any of these to be effective [20,21]. Pentoxifylline, ticlopidine, nicotinamide and clofazamine have all been tried [22–24]. There are several reports in small open studies of approximately 50% of the patients responding to topical PUVA (application of 8-methoxypsoralens [methoxsalen] to the skin prior to treatment with ultraviolet A light) [25–27]. Non-steroidal systemic immunosuppression with cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil or the tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) antagonist infliximab have been reported to be beneficial in a few cases [28–31]. Pulsed dye laser treatment may improve telangiectasia and erythema but there is a risk of skin breakdown [32]. There are reports of good results following excision and grafting [33], although the disease may recur locally. In most cases, cosmetic camouflage is the preferred option.

Diabetic dermopathy (shin spots)

This is the most common dermatologic condition associated with diabetes, occurring in up to 50% of patients with diabetes but also in up to 3% of adults without diabetes; subjects without diabetes usually have only one or two lesions whereas most patients with diabetes have four or more [34,35]. Men are more commonly affected and it is also more prevalent in patients over 50 years of age and in long-standing diabetes. The condition is associated with the three most common microangiopathic complications of diabetes: neuropathy, nephropathy and retinopathy [36]. There is also an association with coronary artery disease and diabetic dermopathy is a subtle sign that suggests more serious complications [37]. The presence of microvascular changes, notably thickening of arterioles and capillaries, led to the term “diabetic dermopathy” [38].

The lesions are well-circumscribed atrophic brownish scars often on the shins, giving the alternative name “diabetic shin spots” (Figure 47.3) [34,35]. The forearms, thighs and bony prominences may also be affected [39]. The lesions are usually bilateral and may appear in crops. Early lesions are oval red papules measuring up to 1 cm in diameter, which slowly develop scaling and a brown color because of the presence of hemosiderinladen histiocytes and extravasated erythrocytes in the superficial dermis [34]. There is no effective treatment, but the lesions tend to resolve over 1–2 years.

Figure 47.3 Diabetic dermopathy, “shin spots.” Courtesy of Professor Julian Verbov, Royal Liverpool University Hospital.

Diabetic bullae (bullosis diabeticorum)

Various forms of bullae have been described in subjects with diabetes, but all are relatively rare [40,41]. Diabetic bullae affect men more than women and are more common in older patients and those with peripheral neuropathy [42]. The conditions usually present as tense blisters, from a few millimeters up to several centimeters in size, on a non-inflammatory base, appearing rapidly and healing over a few weeks without scarring (Figure 47.4). The feet and lower legs are the most common sites, followed by the hands. Electron microscopy studies demonstrate a subepithelial split at the level of the lamina lucida and immunofluorescence studies are negative [43]. Other causes of subepithelial blisters, including the autoimmune blistering diseases porphyria cutanea tarda, pseudoporphyria and infections such as bullous impetigo.

Diabetic thick skin

The thickness of the skin is largely attributable to the filamentous proteins of the dermis, of which collagen is by far the most abundant. Compared with normal subjects, the collagen bundles in the dermis of patients with diabetes are thickened and disorganized, as a result of irreversible non-enzymatic glycation, cross-linking and “browning” of protein. Collagen normally turns over slowly; the formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) damages the protein thereby reducing the ability of enzymes such as collagenase to remodel the collagen fibers [44]. Gradual and irreversible modification of collagen, elastin and other structural dermal proteins is part of the physiologic aging process, but is accelerated in diabetes, especially if poorly controlled.

Browning of collagen results in yellow skin discoloration, best seen on the palms and soles of patients with diabetes. The skin of patients with diabetes is measurably thicker than in subjects without diabetes [45] and shows loss of elasticity [46]. In some studies, skin thickness relates to duration of diabetes [47] and in others to the presence of complications such as neuropathy [48]. Skin thickness is usually clinically insignificant, but may, if advanced, lead to the specific complications of “diabetic hand syndrome” and diabetic scleredema [49]. The combination of thick tight waxy skin and limited joint mobility has been called cheiroarthropathy and is present in 30–40% of patients with T1DM [50].

Diabetic hand syndrome

Up to 75% of subjects with diabetes over 60 years of age are affected, although the incidence is not closely related to the duration of disease or metabolic control [51,52]. Milder skin thickening may develop in up to 20% of individuals without diabetes, but occurs at an older age. The early changes include thickening of the skin over the dorsum of the hands and digits, especially the proximal interphalangeal joints (sclerodactyly). The interphalangeal joints are particularly susceptible and may present as painful stiff fingers. In a minority of patients, the condition progresses to cause a fixed flexion deformity of the fingers and Dupuytren contracture, while soft tissue thickening of the wrist may cause carpal tunnel syndrome by compression of the median nerve. More extreme cases present with a tight waxy appearance together with pebbly pads over the knuckles and distal fingers (Garrod’s knuckle pads).

Scleredema of diabetes

This is marked dermal thickening, commonly involving the posterior aspect of the neck and upper parts of the back, and extending to the face, arms and abdomen with more severe involvement. It has a prevalence of 2.5% in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and is found particularly in those who are overweight and with poorly controlled diabetes [53]. Histology of the condition shows dermal thickening which contains large collagen bundles and an increased number of mast cells [49]. Scleredema, with similar morphologic changes, may follow chronic streptococcal infection of the skin, often involving the lower legs. Scleredema is reported to respond to ultraviolet light [54].

Acanthosis nigricans

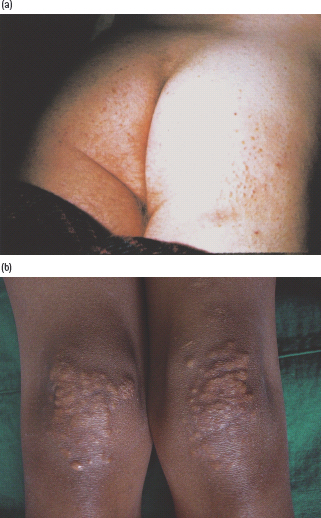

This rare condition is characterized by a velvety papillomatous overgrowth of the epidermis, which is usually hyperpigmented. The flexural areas, particularly the axilla, inguinal region, inframammary region and neck, are most frequently affected (Figure 47.5). Rarely, more generalized changes involve the knuckles and other extensor surfaces, with verrucous patches and hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles. Histologic features include extensive folding and thickening of the epidermis, with increased numbers of melanocytes, which accounts for the dark color.

Figure 47.5 Acanthosis nigricans, showing typical dark velvety appearance: (a) in the axilla; (b) in the groin. Figure 47.5(b) courtesy of Dr. S. Mendelsohn, Countess of Chester Hospital, Chester.

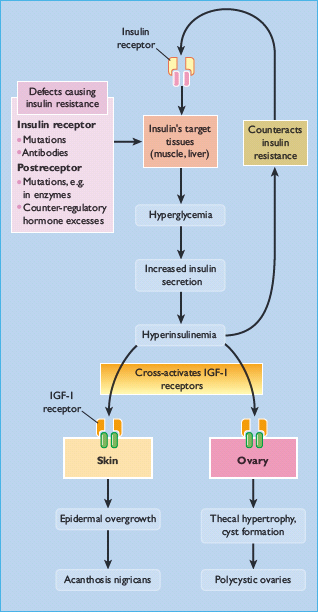

Severe and widespread acanthosis nigricans is usually a manifestation of internal malignancy, often of the gastrointestinal tract. The more limited presentation is associated with various endocrine disorders, which share the common features of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia: these include diabetes mellitus, acromegaly, Cushing disease and polycystic ovarian disease, obesity, genetic and autoimmune insulin receptor defects and lipoatrophic diabetes [55–57]. It is presumed that hyperinsulinemia induced by insulin resistance activates insulin-like growth factor I (IGF- I) receptors, which are closely related to insulin receptors, on various tissues [58]. In the skin, stimulation of IGF-I receptors on keratinocytes could lead to excessive epidermal growth (Figure 47.6).

Figure 47.6 Suggested relationship of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia to acanthosis nigricans. Raised insulin levels may act on insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) receptors in the skin to cause epidermal overgrowth. Similar events in the ovary could lead to polycystic ovary disease which is also associated with insulin-resistant states.

Acanthosis nigricans can be disfiguring and upsetting for the patient. Mild peeling agents such as 5% salicylic acid in a bland cream may be helpful. The condition usually partially regresses if the hyperinsulinemia can be successfully reduced.

Eruptive xanthomas and hypertriglyceridemia

Eruptive xanthomas are caused by hypertriglyceridemia with elevated serum levels of chylomicrons or very low density lipo-proteins. This can occur in diabetes, especially if poorly controlled. The lesions are caused by triglyceride deposition in the skin and present as small red or yellow nodules measuring up to 0.5 cm diameter. They occur predominantly on the extensor surfaces of the limbs and buttocks; the onset is usually rapid and lesions frequently occur in groups or crops (Figure 47.7). Men are more commonly affected. Although xanthomas may itch initially, they are usually asymptomatic. Lesions usually regress slowly within months after hypertriglyceridemia has been corrected by lipid lowering drugs or improved glycemic control.

Vascular changes

Skin conditions develop as manifestations of chronic diabetic complications affecting both small and large vessels. A number of these changes, particularly those causing erythema, are associated with longstanding diabetes (Table 47.2).

Table 47.2 Vascular changes.

| Diabetic erythema and rubeosis Periungual telangiectasia Calciphylaxis Acral dry gangrene |

Rubeosis faciei

Facial erythema can occur in people with diabetes, with the intensity of coloration dependent on the vascular engorgement in the superficial venous plexus [59]. The changes occur as a result of altered vascular tone or diabetic microangiopathy. Capillary microscopy has demonstrated venular dilatation people with diabetes with this condition. It appears more obvious in fair-skinned individuals and can be difficult to distinguish from normal facial redness in the general population [60]. Hypertension is common in these patients and may exacerbate the capillary damage.

Periungual telangiectasia

Erythema of the skin surrounding the nail bed resulting from the dilatation of proximal nailfold capillaries is an excellent marker of functional microangiopathy [61]. It can occur in up to 49% of those with diabetes. Even though connective tissue diseases can exhibit periungual tengiectases, the lesions are morphologically different. In patients with diabetes, isolated homogenous engorgement of venular limbs is seen; whereas mega-capillaries or irregularly enlarged loops are observed in those with connective tissue disease [62]. Different capillary changes can be observed in those with recently diagnosed diabetes than those with long-standing disease. In patients with advanced microvascular disease or following prolonged periods of poor control, small hemorrhages or vascular occlusion (leading to localized areas of non-perfusion) may occur. Nailfold capillaries are thought to reflect the general status of the microcirculation and have been used in detailed studies of functional changes of diabetic microangiopathy.

Erysipelas-like erythema

This manifests as well-demarcated patches of cutaneous reddening, occurring on the legs and feet of patients with diabetes and microcirculatory compromise. It can be mistaken for erysipelas, but is differentiated by the lack of associated fever, leukocytosis or elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. This finding can correlate, in some cases, with destructive lesions of the underlying bone [63]. The pathogenesis of erysipelas-like erythema may be small vessel occlusive disease with compensatory hyperemia.

Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis is a small-vessel vasculopathy occurring in patients with renal failure and sometimes in those with diabetes. It is characterized by mural calcification, intimal proliferation, fibrosis and thrombosis [64]. The lesions start as small red tender areas of skin which become ischemic leading to the development of subcutaneous nodules and poorly healing, necrotizing skin ulcers. They can serve as a portal of entry for infectious agents. The prognosis in those with calciphylaxis is poor because of impaired wound healing and infection leading to sepsis. Aggressive analgesic treatment may be required for ischemic pain, along with optimal blood glucose control and weight reduction [65].

Macrovascular changes

Cutaneous signs of ischemia in the lower limbs include cold or cyanosed feet, erythema, hair loss and atrophy. Patients with diabetes and both venous insufficiency of the lower legs and arterial disease are particularly prone to developing non-healing ulcers; these frequently become superinfected and can be very troublesome to manage. Patients with diabetes have a higher incidence of large-vessel disease than the non-diabetic population. A sign of large-vessel disease is dependent rubor with delayed return of color (>15 seconds) after pressure has been applied to the skin. Patients with diabetes are also prone to venous stasis ulcers as many of them are obese and this in turn leads to increased lower extremity venous pressure. Venous hypertension and skin breakdown at sites of increased venous pressure ensues, leading to venous ulcers. Neuropathy, with lack of pain sensation, also contributes to foot ulceration. Repeated trauma and increased shear forces affect the skin without the usual protective mechanisms which are impaired by peripheral neuropathy, leading to further skin breakdown [62].

Infections

Studies have shown that no significant increase in the prevalence of cutaneous infections occurs in most subjects with diabetes and the strength of previously assumed associations have been questioned [66]; however, poor glycemic control can increase the risk of infection by causing abnormal microcirculation, decreased phagocytosis, impaired leukocyte adherence and delayed chemotaxis [67]. Infections occurring at presentation or with poor glycemic control are shown in Table 47.3.

Table 47.3 Cutaneous infections associated with diabetes.

| Yeast infections (candidiasis) Bacterial infection (boils and sepsis) Erythrasma Malignant otitis externa Necrotizing fasciitis Phycomyces infections |

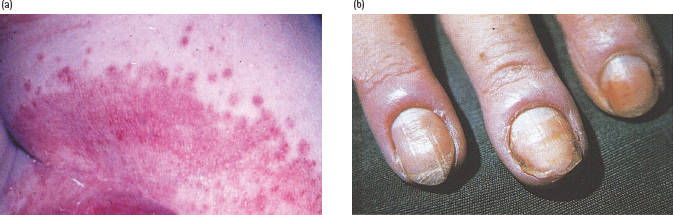

Candida infection

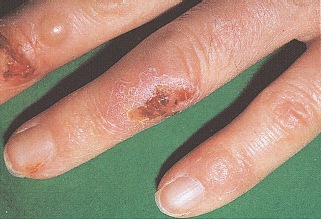

Infection with Candida albicans may be a presenting feature of diabetes or manifest as a complication of poorly controlled diabetes. The infection appears as erythematous papules with satellite pustules and can affect the flexural areas in the body (Figure 47.8a), the vulva and penis, and also the nail margins, causing paronychia (Figure 47.8b). In women, vulvovaginitis is the most common manifestation and presents with pruritus vulvae that can be intense and distressing. The vulva appears erythematous and fissured, with peripheral pustulation in severe cases. It may be particularly troublesome while a patient is hyperglycemic and glycosuric [68]. Candidal balanitis, balanoposthitis and phimosis occur less commonly in men, but could be a presenting feature [69]. Candidal angular stomatitis and an atrophic tongue resembling median rhomboid glossitis are oral manifestations of diabetes. Oral candidiasis occurs more commonly in patients with diabetes who smoke or wear dentures [70]. Candidal intertrigo occurs on opposing surfaces under the breast, in the groins and axillae, or in the folds of the abdominal skin. Scratching of the areas involved with Candida infection can result in bacterial superinfection.

Figure 47.8 Candida infections in patients with diabetes. (a) Flexural infection showing satellite lesions. (b) Chronic paronychia caused by Candida albicans. Note swollen and erythematous nailfolds.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree