- The classification of diabetes mellitus is based on four main categories: Type 1, Type 2, other specific types, and gestational diabetes mellitus

- Impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glycemia are high-risk states collectively termed “intermediate hyperglycemia”

- Type 2 diabetes is a diagnosis by exclusion and as more specific causes are found these will move out of the type two category into other specific types

- Measurement of glucose continues to be the mainstay of diagnosis. In the symptomatic person a single abnormal value, either casual or fasting, is often enough to confirm the diagnosis. In asymptomatic individuals two abnormal values are required and an oral glucose tolerance test may be needed

- The diagnosis of diabetes can not be excluded by measuring fasting plasma glucose alone

- HbA1c has major advantages over glucose testing in terms of convenience and lack of variability, although it is not adequately quality assured or standardized in many places, and is costly. Nonetheless, it is already recommended in some countries as an alternative diagnostic test. This is likely to become more widespread

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a disease of antiquity (see Chapter 1). A treatment was described in the Ebers papyrus and as long ago as 600 BC two main types were distinguished. Perhaps the most famous description was by Arateus the Cappadocian who talked of the melting down of flesh into urine and of the end being speedy. Over the ensuing centuries sporadic descriptions were noted, with Maimonides in Egypt pointing out its relative rarity. It was attributed to a salt-losing state although the sweetness of the urine had long been known. Undoubtedly, virtually all of these accounts referred to type 1 (T1DM) or late type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

Diabetes was better recognized in the 17th and 18th centuries, with the association with obesity noted in some cases. The obvious breakthrough came in the 17th century with the demonstration of excess glucose in the urine and later also in blood.

The presence of excess ketones was shown in the 19th century. A clear description of the two main types of diabetes appeared at the end of the 19th century, with the distinction being made between that occurring in young people with a short time course before ketoacidosis supervened, and that found in older people who were obese. Over the next decades these became known as juvenile-onset diabetes and maturity-onset diabetes, although it was generally stated that the latter was just a milder form of the disease. Diagnosis now depended on glucose measurement with some using glucose tolerance tests. There were no standard criteria for these initially, although glucose levels were clearly above normal. Diagnosis usually occurred after clinical development of the disease with the combination of symptoms with raised glucose in the blood or glycosuria being diagnostic, together with ketonuria in the juvenile-onset form.

A further breakthrough occurred with the work of Himsworth in 1936. Himsworth’s work showed that people with diabetes could be divided into insulin-resistant and insulin-sensitive types, with the former much more common in those with the maturity-onset variety [1]. The next milestone was the development of the radioimmunoassay for insulin which allowed the unequivocal demonstration of insulin deficiency, or indeed absence, in those with juvenile-onset diabetes while levels were apparently normal or raised in those with maturity-onset diabetes.

At that time, diabetes was still considered to be a relatively uncommon disorder occurring predominantly in Europids. The World Health Organization (WHO) began to take note and held its first Expert Committee meeting in 1964 [2]. The real breakthrough, however, in terms of diagnosis and classification came in 1980 with the publication of the second Expert Committee report [3] shortly after the report from the National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG) in the USA in 1979 [4]. These events form the starting point for the diagnostic criteria and classification used today.

Definitions

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder of multiple etiologies. It is characterized by chronic hyperglycemia together with disturbances of carbohydrate, fat and protein metabolism resulting from defects of insulin secretion, insulin action or both [6]. The relative contribution of these varies between different types of diabetes. These are associated with the development of the specific microvascular complications of retinopathy, which can lead to blindness, nephropathy with potential renal failure, and neuropathy. The latter carries the risk of foot ulcers and amputation and also autonomic nerve dysfunction. Diabetes is also associated with an increased risk of macrovascular disease.

The characteristic clinical presentation is with thirst, polyuria, blurring of vision and weight loss. This can lead to ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar non-ketotic coma (see Chapter 19). Often, symptoms are mild or absent and mild hyperglycemia can persist for years with tissue damage developing, although the person may be totally asymptomatic.

Classification

There was awareness of different grades of severity of diabetes for many centuries; however, the possibility that there were two distinct types only emerged at the beginning of the 20th century. Even then there was no real clue to distinct etiologies. In the 1930s, Himsworth suggested that there were two phenotypes. The first real attempt to classify diabetes came with the first WHO Expert Committee on Diabetes Mellitus which felt that the only reliable classification was by age of onset and divided diabetes into juvenile-onset and maturity-onset disease [2]. There were many other phenotypes in vogue at that time including brittle, gestational, pancreatic, endocrine, insulin-resistant and iatrogenic diabetes, but for most cases there was no clear indication of etiology. Clarity began to emerge in the 1970s with the discovery of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotypes common in juvenile-onset diabetes and the discovery of islet call antibodies. This gave a clear indication that younger patients with diabetes, all of whom required insulin therapy, had an autoimmune disorder.

The beginning of the modern era came with the second WHO Expert Committee [3] which reviewed and modified the revised classification published by the National Diabetes Data Group [4]. This proposed two main classes of diabetes: insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM; type 1) and non-insulin-dependent diabetes (NIDDM; type 2) together with “other types” and gestational diabetes. There were also two risk classes: previous abnormality of glucose intolerance (PrevAGT) and potential abnormality of glucose tolerance (PotAGT) which replaced previous types known as pre-diabetes or potential diabetes.

The 1980 classification was revised further in 1985 [5] and reverted to clinical descriptions with retention of IDDM and NIDDM but omission of type 1 and type 2. Malnutrition-related diabetes mellitus was also introduced in recognition of a different phenotype found particularly in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) was also introduced as a high risk class.

Based on increasing knowledge, WHO revisited the classification in 1999 [6] as did the American Diabetes Association (ADA) [7]. It was recognized that the terms IDDM and NIDDM, although superficially appealing, were often confusing and unhelpful – as in patients with insulin-treated T2DM. The new classification attempted to encompass both etiology and clinical stages of the disease as well as being useful clinically. This was based on the suggestion of Kuzuya and Matsuda [8]. This acknowledges that diabetes may progress through several clinical stages (e.g. from normoglycemia to ketoacidosis) while having a single etiologic process such as autoimmune attack on the β-cells. Similarly, it is possible that someone with T2DM can move from insulin requirement to no pharmaceutical intervention through modiication of lifestyle. The main classes are T1DM, T2DM, other specific types and gestational diabetes (Table 2.1). It should be noted that T2DM is largely categorization by exclusion. As new causes are discovered so they will be included under “other specific types” as has occurred for maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY).

Table 2.1 Etiologic classification of disorders of glycemia. Adapted from World Health Organization [6].

| Type 1 diabetes (β-cell destruction) |

|

| Type 2 diabetes (insulin resistance with insulin hyposecretion) |

| Other specific types (Table 2.2) |

| Gestational diabetes (includes former categories of gestational IGT and gestational diabetes) |

IGT, impaired glucose tolerance.

The classification was revisited by WHO in 2006, but no further modification was introduced, and it will be examined again in 2010 when at most minor amendments will be made. IGT was removed from the formal classification of types of diabetes – logically, as it is not diabetes – but was retained as a risk state. Impaired fasting glycemia (IFG) was introduced as another risk state. This was particularly important in many countries where glucose tolerance tests are rarely performed in practice outside of pregnancy so that IGT was not diagnosed and IFG, although not strictly equivalent, has been used as an easily obtained risk marker.

Type 1 diabetes

T1DM is primarily caused by β-cell destruction although some insulin resistance is also present (see Chapter 9). After the initial stages, insulin is required for survival. In Europids >90% show evidence of autoimmunity with anti-glutamine acid decarboxy-lase (anti-GAD), anti-tnsulin and/or islet cell antibodies detectable. It shows strong association with specific alleles at the DQ-A and DQ-B loci of the HLA complex [9]. Not all subjects with the clinical characteristics of T1DM show these associations with autoimmunity although they are ketosis-prone, non-obese and generally under the age of 30 years. In non-Europid populations, up to 80% may show no measurable autoantibodies [10]; these are referred to as having idiopathic T1DM. As with autoimmune diabetes, however, there is clear loss of β-cell function as measured by low or absent C-peptide secretion. Diabetes occurring before the age of 6 months is most likely to be monogenic neonatal diabetes rather than autoimmune T1DM (see Chapter 15) [11].

In addition to the typically young people with acute-onset T1DM, there is an older group with slower onset disease. They may present in middle age with apparent T2DM but have evidence of autoimmunity as assessed by GAD antibody measurements and ultimately become insulin-dependent. This is referred to as latent autoimmune diabetes of adults (LADA) [12].

Type 2 diabetes

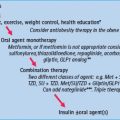

By far the majority of people with diabetes worldwide have T2DM. This is characterized by insulin resistance with relative insulin deficiency (i.e. patients secrete insulin, but not enough to overcome the insulin resistance) (see Chapters 10 and 11). Typically, they do not require insulin to survive but often will eventually need insulin to maintain reasonable glycemia control, often after many years.

The precise molecular mechanisms underlying T2DM are not known. Major efforts have been made to discover underlying genetic abnormalities but with only modest success (see Chapter 12). The most promising to be date has been TCF7L2 [13] which may have a role in insulin secretion but this does not explain diabetes susceptibility in the majority of subjects. What is clear is that T2DM is closely associated with obesity and physical inactivity, and the westernization of lifestyles. The dramatic increase in T2DM over the past two decades has been closely paralleled by the rise in obesity worldwide. Both obesity, particularly visceral adiposity, and physical inactivity cause insulin resistance which will result in diabetes in those with only a small capacity to increase insulin secretion. The incidence of T2DM also increases with age, which may be related to decrease in exercise and muscle mass; however, as the incidence increases so T2DM is being found at younger ages and it is now not uncommon in adolescence in many ethnic groups.

T2DM occurs in families so that those with a first-degree relative with diabetes have an almost 50% life-time risk. There is also marked variation between different ethnic groups. Thus, those of Polynesian, Micronesian, South Asian, sub-Saharan African, Arabian and Native American origin are much more prone to develop diabetes than Europids.

T2DM is a diagnosis by exclusion and the prevalence may fall as causes are identified, but this is likely to be a slow process.

Other specific types of diabetes

Diabetes occurs both as a result of specific genetic defects in insulin secretion and action and in a range of other conditions (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2 Other specific types of diabetes. Adapted from World Health Organization [6].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree