- There is generally low adherence of both people with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and care providers to recommended treatment guidelines.

- Current opinion advocates a multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of T2DM. This includes system support to encourage use of evidence-based guidelines, reorganization of practice systems and team functions, support for patient self-management, improved access to expertise, and enhanced availability of clinical information to facilitate monitoring and feedback on physicians’ performance.

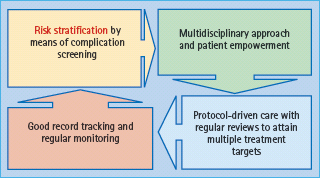

- The key elements of quality diabetes care delivered by a multidisciplinary team include periodic risk stratification, protocol-driven care with regular review, patient empowerment, treatment-to-target, and good record keeping to monitor clinical progress and outcomes.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), four chronic non-communicable diseases – diabetes, cancer, respiratory and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) – account for 60% of global deaths (i.e. 35 million deaths per year) [1]. In Europe and China, 30–40% of patients with acute myocardial infarction have a known history of diabetes. In the remaining subjects, 70% of patients have either diabetes or intermediate hyperglycemia on formal 75-g oral glucose tolerance testing [2,3]. In addition, diabetes and hypertension frequently coexist. Both are important considerations in the majority of cardiovascular deaths worldwide, which are estimated to be 18 million annually. The number of people with diabetes is projected to increase from 285 million in 2010 to 435 million by 2030 [4]. The resulting increase will lead to considerable losses in productivity as well as greatly increasing the burden on health care systems.

Treatment of diabetes and associated complications is costly. In 2006, the WHO estimated that in both developing and developed areas, 2.5–15% of health care budgets were spent on diabetes-related illnesses. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) also estimated that 7–13% of annual health care expenditure was spent on treatment of diabetic complications [5]. The total direct annual costs of diabetes in eight European countries were estimated at €29 billion, with an estimated yearly cost of €2834 per patient [6]. In the USA, diabetes is associated with an annual direct medical expenditure of $91.8 billion. The per capita cost was estimated to be $13243 for individuals with diabetes compared to $2560 for those without [7]. In China, one of the countries with the most rapid increase in diabetes prevalence, $558 billion in national income is expected to be lost over the next 10 years as a result of premature deaths caused by non-communicable diseases including heart disease, stroke and diabetes [8].

Early diagnosis and aggressive control of risk factors can prevent complications in both type 1 (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [9–11]. International organizations such as the IDF, as well as many national organizations, have published clinical recommendations and set standards to guide clinical practice, in order to optimize metabolic control and prevent complications [12].

Evidence for optimization of diabetes control

To date, most evidence supporting the beneficial effects of optimal diabetes care on clinical outcomes [10,13,14] were collected under closely supervised clinical trial conditions. In the Diabetes and Complications Clinical Trial (DCCT), which lasted for 6.5 years, patients with T1DM treated intensively had an HbA1c level 2% (22mmol/mol) lower than those who were conventionally treated (7.2% vs 9.1%, 55 vs 76 mmol/mol). After the study was completed, the authors continued to follow these patients in the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study. There was progressive deterioration in glycemic control once these intensively treated patients returned to their usual care setting; however, patients previously treated conventionally also improved, and both groups converged to achieve HbA1c levels of 8% (64 mmol/mol) [15]. Despite this convergence, patients previously treated intensively maintained over 50% risk reduction in all diabetes-associated complications, including cardiovascular events [16].

Similar findings have also been reported following the post-UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS). People with T2DM who were previously treated with an intensive regimen continued to have lower rates of complications and all-cause mortality than patients treated conventionally, 10 years after discontinuation of the trial [17]. In the Steno-2 Study, individuals were treated intensively in an attempt to attain control for all major risk factors (HbA1c, blood presssure [BP] and low density lipoprotein [LDL] cholesterol), and had 50–60% risk reduction in microvascular and macrovascular complications compared with those conventionally treated [18]. As in the DCCT and UKPDS, in the post-Steno Study period, people who had been treated intensively in the main trial maintained more than 60% risk reduction in all-cause death compared with those conventionally treated for 13.3 years [19]. Findings from these landmark studies clearly demonstrate the beneficial effects of achieving risk factor control during the early course of disease to achieve long-term benefits.

Diabetes care – the reality

Despite the evidence, national and international surveys have indicated that diabetes management remains suboptimal, regardless of the studied populations and health care settings. It should also be remembered that most of these recommendations, guidelines, surveys and studies emanate from settings, countries and areas that are relatively well-resourced.

According to the National Health and Nutritional Examination Surveys (NHANES), conducted between 1988–1994 and 1999–2002 in the USA, amongst patients with diabetes aged 18–75, although there was a non-significant reduction in the proportion of patients with HbA1c >9% (>75mmol/mol), since the numbers of patients with HbA1c 6–8% (64–86mmol/mol) increased, there was no significant change in mean HbA1c between these intervals [20]. In the 1999–2002 survey, there was increased use of multiple antidiabetic agents for control [21], yet nearly half continued to have HbA1c levels greater than the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendation, of 7% and 20% had HbA1c > 9% (>75mmol/mol).

There was also no significant change in the distribution of blood pressure, 33% having BP >140/90mmHg. In the 1999–2002 survey, 60% achieved LDL cholesterol concentrations of <3.4mmol/L and received annual screening for eye and foot complications. The levels of care were noted to be suboptimal, especially in females and in those under the age of 45 years [22,23]. Thus, between these surveys, some improvements were documented but many problems remained.

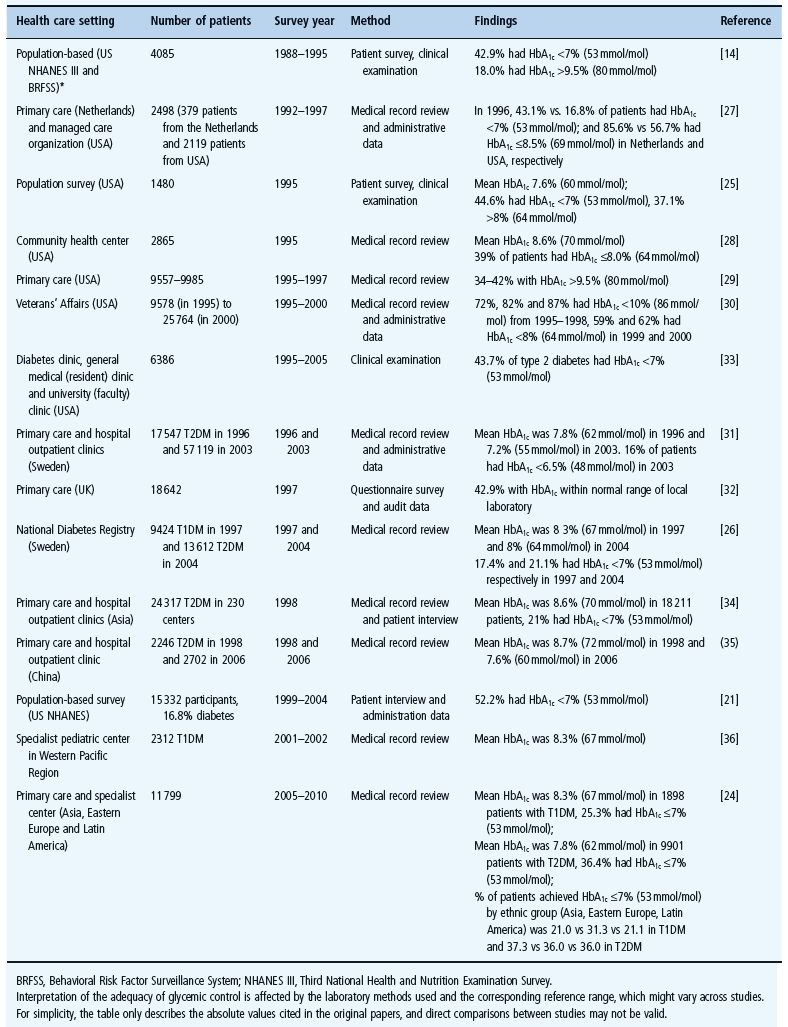

Tables 57.1–57.3 summarize the adequacy of glycemic, blood pressure and lipid control in various settings during the last two decades. Despite much data, there has been little change in average values attained or percentage of patients reaching treatment goals.

Table 57.1 Adequacy of glycemic control in various health care settings in patients with type 1 (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Table 57.1 summarizes adequacy of glycemic control from the 1988–1994 NHANES, up to the latest International Diabetes Management Practice Study (IDMPS) conducted in 2005 [24]. The latter is a 5-year survey documenting changes in diabetes treatment practice in developing regions including Asia, Eastern Europe and Latin America. It shows that only 37% of people with T2DM achieved HbA1c ≤7% (53mmol/mol). The results were similar in both developed and low and middle income countries [14,21,24–26], different health care settings, primary care [27–32] and specialist centers [33–36].

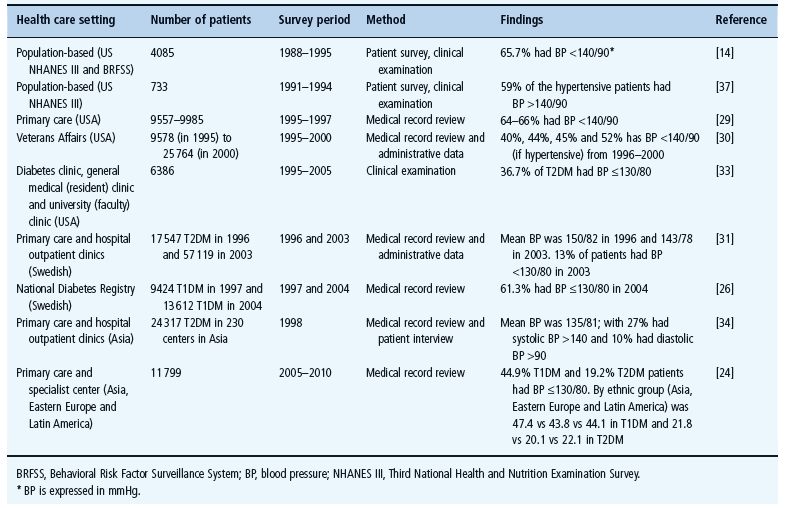

Table 57.2 summarizes adequacy of blood pressure control in the same period. The blood pressure target in earlier years was 140/90 mmHg, when approximately 40–60% of people with T2DM achieved target [14,29,37]. There was a tendency to improvement in the study conducted by the Department of Veteran Affairs in the USA. In this study, conducted between 1996 and 2000, the proportion of people with T2DM achieving the target blood pressure increased from 40% to 52% [30]. The DiabCare studies in Asia demonstrated that over 70% and 90% of people with T2DM were able to achieve the target of systolic and diastolic blood pressure of ≤140 and ≤90mmHg, respectively [34]. Emerging evidence of the importance of blood pressure control led to the target blood pressure being revised to <130/80mmHg. This is not accompanied by further improvement in terms of rate of achievement of targets. Recent studies in different countries and settings showed that only half of people with T2DM were able to achieve the target of 130/80 mmHg [24,26,31,33].

Table 57.2 Adequacy of blood pressure control in various health care setting in type 1 (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

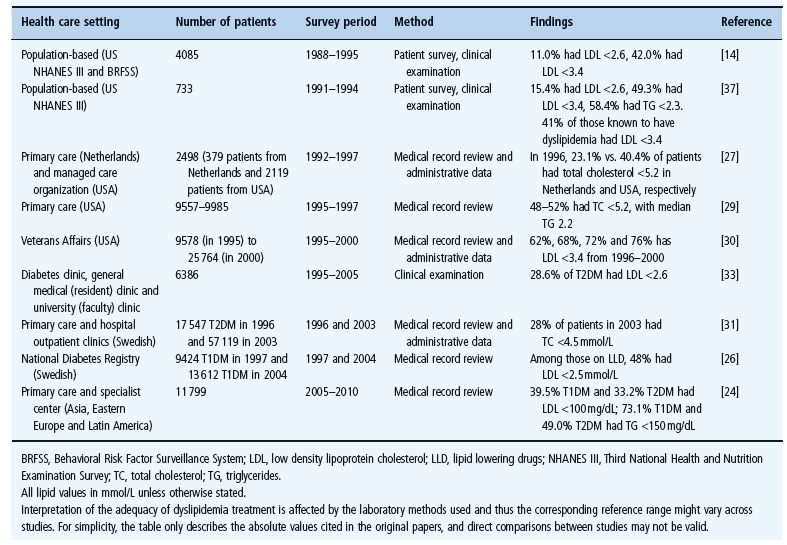

With regard to lipid control (Table 57.3), there was a slow but gradual improvement, probably because of the availability of effective treatment of LDL cholesterol with 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors. In the 1980s and early 1990s, the rate of achievement of target LDL cholesterol <2.6 mmol/L was around 10–15% [14,37]. This had increased to approximately 25–30% subsequently [24,27,29,31,33]. For those on HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, as illustrated from a study in Sweden, nearly half of patients were able to achieve the target [26].

Table 57.3 Adequacy of lipid control in various health care setting in type 1 (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

There are obvious limitations in these studies including heterogeneity of populations in different studies, retrospective reviews, incomplete documentation for medical record review and inaccuracy for claims data. Despite the limitations and lack of comparability of the many studies, the results summarized in Tables 57.1–57.3 indicate the same trend. It should also be noted that, most of these surveys come from well-resourced settings and developed countries, where laboratory assessment for HbA1c is readily available.

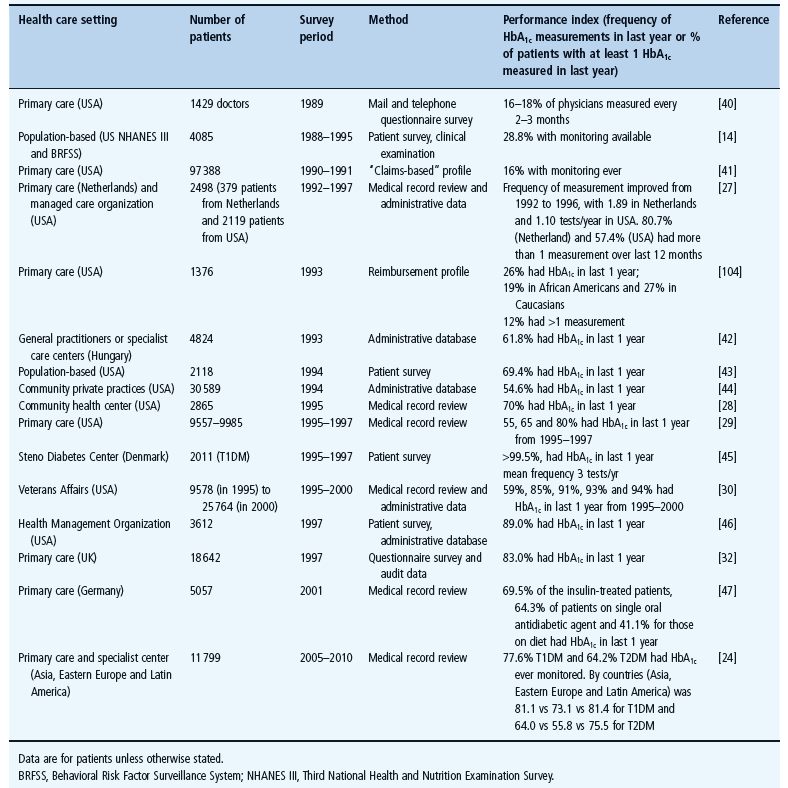

The Institute of Medicine has defined quality of care as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” [38,39]. There is ongoing controversy as to the degree to which outcomes can be directly related to processes of care, yet both are considered as important measures of quality. Thus, the degree of adherence to recommended guidelines, based on available clinical evidence, provides guidance to the degree of quality of care. Table 57.4 summarizes attempts to address this issue specifically and includes surveys that assess quality of care as measured by frequency of measurement for HbAlc. In early years, less than one-third of patients received HbAc monitoring [14,40,41]. Since the early 1990s, with the availability of results from the DCCT and UKPDS, the frequency of monitoring has gradually improved [27–29,42–44]. Recently, more than 90% of patients have HbA1c regularly monitored in specialist clinics such as the Steno Diabetes Center [45] and in some primary care settings [30,46]. Elsewhere, monitoring is available in 70–80% of patients [24,32,47].

Table 57.4 Frequency of HbA1c monitoring in various health care settings in type 1 (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

It is important to note that there is often a discrepancy between doctors’ claims of frequency of monitoring and that occurring in practice. Although there appears to have been some improvements in the care processes over time, this has not been matched by improvement in rates of achieving treatment targets (Tables 57.1–57.3).

Discrepancy between evidence-based care and reality

The efficacy of optimization of diabetes control has been confirmed in randomized controlled trials conducted with stringent clinical trial protocols; however, despite improvements in some processes of care such as monitoring of HbA1c, this has not been matched by improvement in rates of achieving treatment targets. In addition, the level of care received by many patients does not meet recommended standards. In a previous survey in USA, only 25% of patients were aware of the term “glycated hemoglobin” or “HbA1c” [43]. Only 72% of the subjects visited a health care provider for diabetes care at least once a year, and approximately 60% received complication screening. Furthermore, despite the proven benefits of many therapeutic agents, many people with diabetes were not prescribed insulin, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or lipid-lowering drugs despite the presence of indications [48–53].

The factors that compromise quality of care have been examined in various studies, but have not been well understood. Nevertheless, some components are obvious.

Patients

Drug compliance by patients receiving chronic medications is consistently reported to be less than 50%, often because of insufficient education and reinforcement [54–56]. Moreover, there is considerable heterogeneity in the patterns and rates of non-adherence to individual components (e.g. diet, exercise, drugs) of a diabetes treatment regimen. Thus, the extent to which people with diabetes adhere to one aspect of the regimen might not correlate with their adherence to other components. Previous studies have shown that only 69% of people with diabetes follow a diet and less than half engage in regular exercise [57]. The reported adherence to self-monitoring of blood glucose ranges from 53% to 70% [58]. Earlier studies have indicated that only 7% of patients with diabetes adhere to all aspects of the treatment regimen [59], while over half made errors with insulin dosage and three-quarters of patients were judged to be in an “unacceptable” category regarding the quality, quantity and timing of meals [60].

In attempts to extrapolate results from clinical trials to daily practice, it is important to individualize interventions taking into account all potential factors. For example, in the elderly, side effects of interventions must be balanced against long-term benefits, limited life expectancy and co-morbidities. Other factors such as education level, access to care, compliance and motivation may also contribute to patient adherence, in addition to treatment-related factors such as adverse effects, polypharmacy and cost [42,43,49]. It is recommended that people with diabetes should be educated about the nature of the disease with particular focus on chronicity and long-term complications, as well as preventability.

Physicians

The key role of health care providers is to equip people with diabetes with knowledge and skills related to self-management, to individualize medical and behavioral regimens, to assist with informed decisions, and provide social and emotional support via a collaborative relationship [61,62]. An important factor is the inertia of physicians in failing to modify the management of patients in response to an abnormal clinical result [63,64]. In a previous study by Kaiser Permanente, one of the major health management organizations in USA, there was on average 15 months and 21 months lapse before escalation of treatment in patients with HbA1c of >8% (64mmol/mol) on metformin and sulfonlyurea monotherapy, respectively [65]. Despite the complexity and rapid advances in diabetes management, generalists often did not perceive the need for further training in the field of diabetes [66–69]. Involvement of other non-medical health care professionals may also not be welcomed in some traditional settings.

Health care system

Traditional medical practice is organized to respond quickly to acute problems, but does not adequately serve the needs of individuals with chronic illnesses, when emphases are to alter behavior and to deal with social and emotional impacts of symptoms as well as disabilities [70]. Health care systems need to ensure that the best possible treatment regimens are administered in order to control disease, alleviate symptoms, inform and support.

Thus, suboptimal quality of care is often caused by combinations of factors relating to the affected individual, to the medical care personnel and to the system of health care delivery. In the IDMPS [24], amongst patients in whom HbA1c, BP and LDL cholesterol measurements were available, only 3.6% of patients attained target values for all three risk factors (BP <130/80mmHg, HbA1c <7% (53mmol/mol) and LDL cholesterol <2.6mmol/L). In this survey, there was considerable heterogeneity between regions of patient-related factors (e.g. age, disease duration, presence of complications, body weight), health care systems (e.g. health insurance coverage, availability of specialist care, training by diabetes educator) and self-care (e.g. self-adjustment of insulin dosage) all being associated with the likelihood of reaching targets. The problem is particularly marked in low and middle income settings where it is exacerbated by multiple demands upon severely limited resources including those imposed by a continuing burden of infectious diseases and other issues such as accidents and injuries.

The evolving concept of disease management

It will be clear from the previous sections that although optimal care improves clinical outcomes in clinical trial settings, this is often not achieved in real clinical situations for the reasons discussed. This has led to attempts to develop models of care based on multidisciplinary approaches.

In recent years, there has been increasing emphasis on management via coordination and organization of individual components of care into a structured system. The latter is further supported by reinforcement through multiple contacts, including not only physician appointments, but also telephone reminders and visits to other health care professionals such as nurse practitioners, dietitians and pharmacists. According to Wagner et al. [70], there are five key elements to improve the outcomes of patients with chronic diseases:

The Steno-2 study provides excellent evidence in support of the benefits of protocol-driven multifaceted care using a multi-disciplinary approach in T2DM [13,18,19]. Patients randomized to the intensive treatment group were managed by a multidisciplinary team according to a protocol that specified a stepwise implementation of behavior modification, smoking cessation, aggressive control of glycemia, BP, lipids and microalbuminuria, and use of an ACE inhibitor and aspirin. The reductions in HbA1c, BP, serum cholesterol and triglycerides levels and albuminuria were all significantly greater in the intensive care group than in the usual care group. These benefits in metabolic control were translated to risk reductions of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality by 53% (95% confidence interval [CI] 27–76%), nephropathy by 71% (95% CI 13–83%), retinopathy by 58% (95% CI 14–79%) and autonomic neuropathy by 63% (95% CI 21–82%). By the end of 13.3 years, patients previously treated intensively had lower all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 0.54; 95% CI 0.32–0.89), cardiovascular mortality (HR 0.43; 95% CI 0.19–0.94) and cardiovascular events (HR 0.41; 95% CI 0.25–0.67) than the conventional care group.

In another multicenter randomized study comparing structured care delivered by a diabetologist-nurse team with conventional care, 60% of patients with T2DM with renal impairment receiving structured care attained three or more predefined treatment goals (HbA1c<7% (53mmol/mol); BP <130/80mmHg; LDL cholesterol <2.6mmHg; triglycerides <2 mmol/L and use of ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker) compared to 20% in the usual care group. After 2 years, patients who attained three or more treatment goals had 60% risk reduction in all-cause mortality and end-stage renal disease (HR 0.43; 95% CI 0.210.86) [71].

Implementation of quality structured care

This concept of disease management emphasizes an organized, proactive multidisciplinary approach to health care in complex and chronic diseases, of which diabetes is a prime example [72,73]. People with chronic diseases should be empowered to improve knowledge and self-management [74,75]. Preferences should be taken into account to individualize treatment plans. Evidence suggests that periodic attendance at a diabetes center [76] and frequent reminders by paramedical staff to reinforce self-management could improve metabolic control, clinical outcomes and survival [13,71,77–84]. Clinical information should be made easily available to provide support. Information technology can be used to monitor adherence to guidelines and provide feedback to the care providers (see Chapter 58) [70,72,85–87].

Provision of structured care to people with T2DM is best implemented through a series of interlinked processes based on these principles. These include risk stratification, protocol-driven care, regular review by a multidisciplinary team, patient empowerment and good record keeping to monitor progress (Figure 57.1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree