The Diagnosis and Management of Infectious Diseases

This chapter is intended as an introduction to some theoretical concepts about infectious diseases. It may be skimmed by physicians who are familiar with these concepts. It should not be omitted simply because it deals predominantly with generalizations, because many of these concepts can be extremely useful.

Special Problems of Children

Children have a special susceptibility to or an increased severity of infections for a number of reasons.

First exposure. Exposure to an agent for the first time (e.g., to parainfluenza or influenza virus) often produces fever and a rather severe illness. A reexposure, such as may occur in an older child or an adult, is more likely to produce a mild illness, modified by the serum antibodies from the first infection, primarily immunoglobulin G (IgG), and by the antibodies in respiratory secretions, predominantly immunoglobulin A (IgA), as described in the section on the common cold (Chapter 2). Young children are also less likely to have cross-reacting antibodies from a previous infection with an antigenically related organism.

Small passages. The smaller passages of children (e.g., the bronchi, the larynx, and the eustachian tubes) are more easily obstructed by edema or secretions.

Young cells. There is considerable laboratory evidence that rapid growth rates such as those seen in fetal tissue make these cells more susceptible to infection with most viral agents (e.g., Coxsackie B viruses infect newborn but not adult mice). It may be that the special susceptibility of newborn humans to some viruses, such as Coxsackie B or herpes simplex, is related to the rapid growth rate of the infant’s cells.

Decreased interferon production may be observed in young cells in cell cultures and in newborn animals, but the relation of this fact to the increased severity of viral infection in newborn animals is unproved.

Immature immunologic defenses. The fetus does not usually synthesize immunoglobulin M antibodies unless exposed to maternal infection. The newborn infant can synthesize IgM antibodies in response to infection but has no antibodies of the immunoglobulin M (IgM) type transmitted through the placenta from the maternal circulation. The importance of serum factors such as IgM in protecting the newborn from infection is not clearly established, but such factors probably would be helpful in providing opsonins to aid phagocytosis. Other immature immunologic functions in the newborn period include decreased complement activity, decreased neutrophil chemotaxis, and less effective cell-mediated immunity.

Clinical Approach to Infectious Diseases

The study of infectious diseases is different from the study of microbiology. Microbiology concentrates on the study of microorganisms, whereas the discipline of infectious diseases concerns itself with the study of patients. In clinical medicine, knowledge about microorganisms is only part of what is necessary to analyze the observations made of a patient with an infection.

Two Approaches

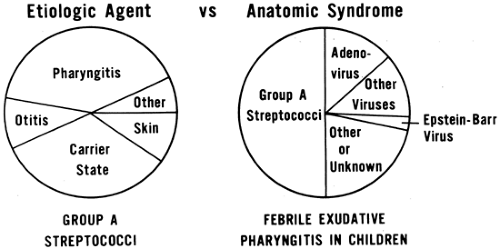

There are two approaches to infectious diseases: the etiologic agent approach and the anatomic syndrome approach (Fig. 1-1). Traditionally, the student’s introduction to infectious diseases is in terms of the particular agent involved. The student learns to identify the characteristics of the infecting organism

and the diseases it may cause. However, patients cannot be easily categorized on the basis of etiologic agents, so that when clinical experience begins, the student must shift viewpoints to that of the clinician and think in terms of anatomic syndromes.1,2 This is an important step in developing skill in clinical diagnosis. Syndromes can be defined in purely empirical and mutually exclusive terms, and a patient’s illness often can be classified into a single anatomic syndrome.

and the diseases it may cause. However, patients cannot be easily categorized on the basis of etiologic agents, so that when clinical experience begins, the student must shift viewpoints to that of the clinician and think in terms of anatomic syndromes.1,2 This is an important step in developing skill in clinical diagnosis. Syndromes can be defined in purely empirical and mutually exclusive terms, and a patient’s illness often can be classified into a single anatomic syndrome.

These two approaches to infectious diseases can be illustrated by the example of group A streptococci and exudative pharyngitis (see Fig. 1-1). In the etiologic agent approach, the various kinds of illnesses that can be caused by Group A streptococci are considered. In the anatomic syndrome approach, a broad, general clinical pattern of the syndrome is defined (e.g., febrile exudative pharyngitis). After that, the various microorganisms that can cause this syndrome are evaluated.

It is important to make the anatomic syndrome diagnosis before trying to determine the specific etiologic diagnosis. This order of priority helps the clinician avoid overlooking reasonable possibilities. Although it is not customary to say, “influenza-like illness, possibly due to influenza virus,” this sequence of phrasing a diagnosis helps remind the clinician that other viruses can produce an illness very similar to that produced by influenza virus. It is also an example of the two-step approach to diagnosis: first a descriptive syndrome diagnosis and second a probable etiologic diagnosis.

Agent versus Syndrome

The word “measles” can refer to either the disease or the virus. Similarly, the words “pertussis,” “chickenpox,” and “influenza” can refer to the syndrome or to the agent. However, many infectious diseases have been recognized that are best regarded as syndromes and that can be caused by a number of different agents. For example, a rubella-like illness can be caused by rubella virus or by other infectious agents. It is best to reserve the use of simple terms such as “rubella” or “measles” for cases in which the etiologic diagnosis is not in doubt; otherwise, terms that describe the syndrome, such as “rubella-like illness” should be used. Confusion does not arise if the agents are referred to by their taxonomic names, i.e., “rubella virus,” “influenza virus,” “Bordetella pertussis,” or “varicella-zoster virus.”

Normal versus Immunocompromised Child

When evaluating a child with a possible infectious problem, the approach may differ depending upon whether the child has a normal or a compromised immune system. The immunocompromising condition may be known, such as a child receiving chemotherapy for a malignancy, or suspected, such as a child with a history of severe, recurrent infections. Susceptibility to infection will vary depending on the nature and severity of the specific immunologic defect. In general, immunocompromised children require prompt and more aggressive therapy. These exigencies may appropriately lead the clinician to institute empiric therapy more readily. Coexisting infectious processes are also more likely in the immune compromised host. Finally, duration of therapy may also need to be lengthened.

Spectrum of Severity

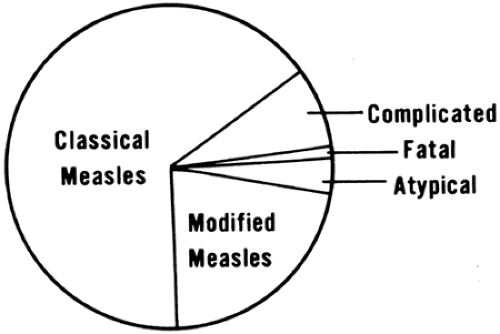

There is a spectrum of severity of clinical illnesses caused by a single etiologic agent (Fig. 1-2). Most diseases are first recognized in their most severe form at autopsy. After the clinical patterns of illness in these fatal cases have been studied, a form of illness of moderate severity can often be diagnosed before death. After techniques have been developed for serologic diagnosis or for isolation of the agent, asymptomatic forms of the disease can be recognized.

The existence of various degrees of severity of any disease must be recognized when making generalizations about it. The physician should not consider diseases in terms of an average of all degrees of severity, because there are important clinical differences in the prognosis for different severities. The clinician must recognize that more vigorous therapy is needed for the severe form than for the milder form of an illness caused by the same agent.

The classic or severe form of a disease often is correctly diagnosed by a nurse, an observant family member, or a school teacher.3 This form should not present any diagnostic difficulty to a physician who has seen the disease, but much more knowledge and skill is needed to diagnose moderate or atypical forms of a disease. Recognition of the mild or asymptomatic forms of an infection usually requires the use of laboratory tests. It is prudent to remember the old adage that atypical presentations of common illnesses are more frequent than classic presentations of rare illnesses.

The Diagnostic Process

Clinical diagnosis is an intellectual process the physician goes through in analyzing a patient’s disease. It is a judgment that begins the moment a patient is first seen and the physician begins to reason from the general nature of the patient’s signs and symptoms to the specific possible illnesses. It ends when the diagnosis cannot be further refined.

Steps in Diagnosis

History and Physical Examination

The first history obtained is usually only an approximation and varies in quality according to the patient’s ability to give information, the doctor’s ability to elicit the necessary information, and the time available.

The experienced clinician forms hypotheses, also called tentative diagnoses or problems, early in the history taking and directs the questions toward testing these hypotheses.4,5 One deliberately keeps the hypotheses broad and allows the history and questioning to shape them. This avoids the tendency to jump to diagnostic conclusions while still keeping the discussion within reasonable limits.

The important details of the physical examination can be completed in a brief period of time and should be complete relative to the disease suspected. Some parts of the examination should be repeated when indicated by the clinical situation.

In both the history and the physical examination, the critical information necessary to the final diagnosis of a complicated illness may not be obtained until the second or third evaluation of the important key features.

Working (Presumptive) Diagnoses

The clinician should always have presumptive (working) diagnoses on which to base laboratory studies and therapy. The presumptive diagnoses should be made early in the evaluation and are based on the history and physical examination, and, in some cases, on the initial laboratory studies.

Types of Diagnoses

Several kinds of presumptive diagnoses can be made for most illnesses,6 as in the following list. Two have been described earlier as part of the two steps in the diagnostic process. A third type is often an emergency or urgent physiologic diagnosis and in pediatrics may be made on an urgent basis before the anatomic or syndrome diagnosis has been clarified.

Anatomic: describing the anatomic area involved (e.g., pharyngitis, pneumonia, or non-purulent

meningitis); also called syndrome diagnoses. These diagnoses should be empirical and descriptive and should be easily agreed upon by reviewers of the data available.

Etiologic: indicating the cause of physiologic or anatomic disturbance (e.g., Shigella, meningococcus, or respiratory syncytial virus). The etiologic diagnosis should be given as the single most probable etiology, along with a list of the other reasonable possibilities, with comments about each possibility.

Physiologic: indicating the disturbances in physiology involved (e.g., respiratory acidosis, congestive heart failure, or endotoxic shock). Therapy directed at a physiologic disturbance is often possible as an immediate measure without knowledge of the etiologic agent involved. The physiologic diagnosis can often be expressed quantitatively (e.g., respiratory acidosis with a blood pH of 7.2 and PCO2of 50 torr).

Physiologic diagnoses should not be confused with theories of pathogenesis. Physiologic diagnoses can be defined operationally by empirical observations, as in shock, cerebral edema, or respiratory acidosis. Theories of pathogenesis cannot be defined by direct observation (e.g., antigen–antibody reaction, latent infection, viremia, and collagen disease).

Progressive Focusing on the Diagnosis

Anatomic syndromes should be defined precisely yet should be broad enough to include all possibilities.5,7 After the anatomic syndrome is diagnosed, clinicians can gradually eliminate etiologic agents until they finally focus on the correct possibility. The principal problem in diagnosis is to consider that correct one. Attempting to make etiologic diagnoses before syndrome diagnoses is like trying to spear a fish. However, when the concept of anatomic syndromes is used, it is like casting a net, catching all the possible causes, then excluding those inconsistent with the data and gradually selecting the most likely.

Overlap of Categories

Patients’ illnesses, especially early in their course, are difficult to categorize into a single syndrome. The diagnosis is gray, not black or white; mixed-up, not pure. This situation is best managed early in the formulation of the patients’ diagnoses or problem lists by being a “splitter” rather than a “lumper” and listing several separate problems rather than combining them. This is described further in a later section.

Pattern Diagnosis versus Physiologic Approach

The most frequent approach to diagnosis in practice is pattern diagnosis.3,8 This involves recognizing and combining clinical features. Fever, red throat, and exudate would be combined as the syndrome or pattern of febrile exudative pharyngitis. The physician then takes the statistical probabilities in terms of age, sex, exposure, and other variables and arrives at a presumptive etiologic diagnosis for that patient, pending the results of the throat culture. Thus, multiple features make an anatomic pattern. The probable causes of that pattern make a probable etiologic diagnosis.

The physiologic approach to clinical diagnosis is most useful when the clinical pattern is unfamiliar to the physician. Such a situation may occur frequently, when the physician has had little clinical experience, or less often, when the experienced clinician encounters an unusual case. In unusual cases, the frequencies of various etiologies for a given pattern are of little value. The physician must then reason from the anatomic location and the physiologic disturbance and has little basis for discriminating among etiologic probabilities. In such cases, nonspecific laboratory studies are of little value. Specific tests, such as biopsy or computed tomography or direct culture of the involved area may be necessary if the illness is severe enough to justify such a study.

Algorithms

Rational approaches to the evaluation of certain clinical syndromes have been developed into algorithms. Overreliance on algorithms, particularly when the rationale behind their development has not been studied and internalized, stunts the diagnostic acumen of physicians in training. Emphasis should be placed on understanding disease processes rather than tracing algorithmic lines. Occasionally, the experienced clinician may find an algorithmic approach to an uncommon illness to be time- and resource-saving.

Presumptive and Final Etiologic Diagnoses

The broader the anatomic diagnosis and the more specific the etiologic possibilities it includes, the more likely it is to include the correct etiologic diagnosis. Like the detective in a mystery story who always has a working hypothesis for the identity of the criminal, the clinician needs to have a presumptive etiologic diagnosis as a guide to practical action for logical therapy.3 If the physician has no presumptive etiologic diagnosis, there is no basis for rational specific therapy. The anatomic syndrome diagnosis rarely needs to be changed, because it is descriptive, and all skilled observers should agree on the descriptive formulation. However, the presumptive etiologic diagnoses may have to be changed when new information is obtained, because presumptive etiologic diagnoses are almost always practical and pragmatic.

The final etiologic diagnosis can be defined as the best diagnosis that can be made when all information, including laboratory data, is complete. The final diagnosis may be made late in the patient’s illness. It need not always be made on the basis of laboratory tests but may be made by the course of the patient’s illness or at a postmortem examination.

Fort Bragg fever, also called pretibial fever because the patients had fever and a rash on the lower legs, was recognized clinically in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, in 1942. The final etiologic diagnosis for this illness was not made until 10 years later, when Leptospira autumnalis, a spirochete, was identified in a soldier’s blood after it had undergone 625 serial passages in guinea pigs.9 Paired sera saved from these patients showed a rise in antibody titer when tested with this leptospira as the antigen. This example illustrates the value of paired sera in making a final laboratory diagnosis and shows how long a final diagnosis can be delayed.

Conclusive Etiologic Diagnoses

These conclusive diagnoses are not as frequent as laypersons might think. For the majority of patients with infectious diseases, a probable etiologic diagnosis is made rather than a conclusive one. However, a conclusive etiologic diagnosis is important because it allows the physician to:

tailor immediate patient care;

stop further unnecessary studies;

adjust therapy more specifically;

give a more accurate prognosis;

learn more about a disease process;

initiate preventive care, when necessary;

ascertain which specific agents are common and severe enough to warrant vaccines; and

recognize potential epidemics

A conclusive etiologic diagnosis allows discontinuance of laboratory studies and may provide guidance for specific antibiotic therapy. It may also reassure the patient or relatives, because it excludes more serious etiologies.

Every conclusive diagnosis increases the physician’s knowledge, whereas unconfirmed diagnoses do not. For the scientific education of the physician, one conclusive diagnosis is worth a thousand equivocal, doubtful, unconfirmed diagnoses. The physician should use all methods available to establish the clinical diagnosis, provided that it is in the patient’s best interest to do so. For the physician to benefit from a final diagnosis obtained later, it is essential to have accurate written observations of the early symptoms and signs so that they can be evaluated and analyzed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree