Genital Syndromes

Definitions

A genital infection can be defined as any infection involving the reproductive organs. “Venereal disease” is an older phrase for a disease usually spread by sexual contact, now referred to as a sexually transmitted disease (STD). Genital and sexually transmitted diseases have important differences: STDs may involve anatomic areas other than the genitalia, and many genital infections are not spread by sexual contact. Therefore, it is useful to keep the working diagnosis of a genital infection in terms of an anatomic syndrome, such as vaginitis, and record the etiologic diagnoses as probabilities or possibilities until confirmed by laboratory methods.

Children can acquire STDs as sexually active teenagers or by sexual abuse of either sex, particularly before complete sexual maturity and before the age when they can tell about the abuse.1,2,3,4

The “traditional” STDs are syphilis, gonorrhea, donovanosis (granuloma inguinale), lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), and chancroid. Many other infections can be sexually transmitted, including chlamydia, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B, hepatitis C, Trichomonas infections, nonspecific urethritis and Reiter’s syndrome, genital herpes, venereal warts (condyloma accuminata), various types of vaginitis, and molluscum contagiosum. Infestations with lice (“crabs”) and mites (scabies) can also be sexually transmitted. Cystitis in the sexually active female may be a result of sexual intercourse, as discussed in Chapter 14. The physician should remember that the presence of one of these diseases should suggest the possibility of others.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is discussed in Chapter 20. Hepatitis B and C infections are discussed in Chapter 13. Congenitally-acquired infections are discussed in Chapter 19.

Implications of Sexually Transmitted Diseases in Children

Sexual abuse of children should always be considered when the cause of a genital infection has been found to be a sexually transmitted pathogen.2,3,4 Implications of commonly encountered STDs in children with regard to the possibility of abuse have been developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and are shown in Table 15-1.

Frequency

In the United States, STDs constitute an epidemic of tremendous magnitude, with an estimated 15 million persons acquiring a new STD each year.5 In the 1980s, chlamydia surpassed gonorrhea as the most common STD. Currently, it is estimated that there are 3 million new cases of chlamydia in the United States each year, compared with 650,000 cases of gonorrhea. The incidence of syphilis has decreased steadily; currently, about 70,000 cases occur each year. However, there is extreme geographic clustering, with half of all new cases reported from only 22 U.S. counties.6

The incidence of herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2 infections has risen to 1 million cases per year. Because herpes viruses cause persistent infection, currently 45 million people (22% of the U.S. adult population) are infected with HSV type 2.7

Each year in the United States, there are approximately 5 million new cases of human papilloma virus (HPV) infections and a similar number of trichomonas infections.5

Prevention of Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Prevention of STDs is based on five major concepts8:

Education and counseling of persons at risk on ways to adopt safer sexual behavior

Identification of asymptomatically infected persons and of symptomatic persons unlikely to seek treatment

Effective diagnosis and treatment of infected persons

Evaluation, treatment, and counseling of sex partners of persons who are infected with an STD, and

Preexposure vaccination of persons at risk for vaccine-preventable STDs (e.g., hepatitis B).

TABLE 15-1. IMPLICATIONS OF COMMONLY ENCOUNTERED STDS FOR THE DIAGNOSIS AND REPORTING OF SEXUAL ABUSE OF INFANTS AND PREPUBERTAL CHILDREN | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The correct use of male condoms is effective in preventing some STDs. Because condoms do not cover all exposed areas, they are more effective in preventing infections transmitted by fluids from mucosal surfaces (e.g., Gonorrhea, Chlamydia, Trichomonas, and HIV) than in preventing those transmitted by skin-to-skin contact (e.g., HSV, HPV, syphilis, and chancroid).8 The most reliable way to avoid transmission of STDs is to abstain from sexual intercourse or to be in a long-term, mutually monogamous relationship with an uninfected partner.8

A recent study assessed the efficacy of valacyclovir in preventing transmission from an HIV-2 seropositive person to their HIV-2 seronegative partner. A total of 1,484 heterosexual, monogamous couples were followed. The HSV-2 seropositive person received once daily valacyclovir. The overall acquisition of HSV-2 among susceptible persons was 3.6% in the placebo group and 1.9% in the valacyclovir group- a 47% relative reduction (p = 0.04).8a

Genital Infections of Males and Females

Genital Ulcers

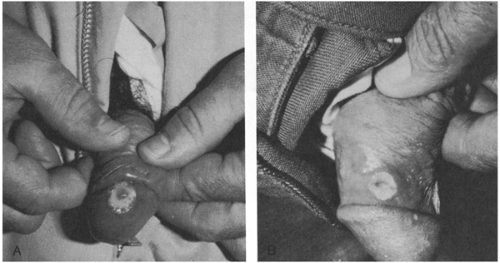

This category includes ulceration of the skin on or near the external genitalia or on the mucosa (Fig. 15-1). Clinical differentiation of the various causes of genital ulcer disease (GUD) is difficult, even if standardized, quantitative diagnostic techniques are used.9 The sensitivity of clinical features in establishing the diagnosis of syphilis, HSV infection, and chancroid was 31–35% in a study of 220 patients with microbiologically established diagnoses.9

Genital ulcer disease (GUD) is important for several reasons. Early treatment of syphilis prevents progression to secondary and tertiary disease. The seroprevalence of HIV is higher in patients with GUD, and it continued to increase among these patients during a period of rapid decline in patients without GUD.10 It is thought that HIV is more readily spread by those with genital ulcers. The causes of GUD are discussed briefly later.

Genital Herpes

HSV is by far the most common cause of genital ulcer disease in the United States. The seroprevalence of HSV has increased 30% over the past 20–25 years in this country.11 Women are infected more readily than are men.12 HSV infection is also the most common sexually transmitted cause of genital ulcers in children.13 The classic description of the disease is that of painful, clustered genital ulcerative lesions. The spectrum of disease, however, is much wider. Longitudinal studies show that 60% of primary HSV-2 infections are asymptomatic.14

Of symptomatic patients, only 40% fit the classic clinical description; over a third have ulcerative lesions outside the genital area, approximately 10% have a single ulcer, about 5% have erosive lesions, and a few have crusting, fissuring, edema, and other atypical manifestations.15 In addition to painful ulcerations, HSV can also produce vaginal discharge and dysuria.16 Necrotizing ulceration of the glans penis (balanitis) has been described.17 Occasionally, finger lesions (herpetic whitlow) are found in addition to the genital lesions.

Of symptomatic patients, only 40% fit the classic clinical description; over a third have ulcerative lesions outside the genital area, approximately 10% have a single ulcer, about 5% have erosive lesions, and a few have crusting, fissuring, edema, and other atypical manifestations.15 In addition to painful ulcerations, HSV can also produce vaginal discharge and dysuria.16 Necrotizing ulceration of the glans penis (balanitis) has been described.17 Occasionally, finger lesions (herpetic whitlow) are found in addition to the genital lesions.

FIGURE 15-1 (A) Syphilitic chancre; (B) chancroid (soft chancre), caused by Haemophilus ducreyi. (Photos from Dr. Larry Lantis.) |

Reactivation of latent infection occurs at varying frequency. Traditionally, it was believed that patients whose primary HSV infection was asymptomatic underwent very few recurrences, and thus presented a low risk of transmission of the infection to others; careful clinical studies have now shown that reactivation and viral shedding occurs with similar frequency in all patients, regardless of whether the primary infection caused noticeable disease.18 Most patients eventually develop clinically apparent lesions. In the majority of patients, the frequency of reactivation declines over time.19 Triggers for recurrence have not been carefully studied. One study concluded that short-term stressors did not increase the frequency of recurrence, but persistent stressors and “total anxiety level” were modestly associated with an increased number of reactivations.20

The gold standard for establishing the diagnosis is viral culture.21 However, the sensitivity of culture depends on the stage of the lesions. About 95% of vesicular lesions will grow HSV, as compared with 70% of ulcerative lesions and 30% of crusted lesions.21 PCR testing is about 30% more sensitive than conventional tissue culture methodology but is also considerably more expensive.22,23 Vesicular fluid can be tested for the viral antigen, and although this may be useful if the result is positive, the test is not very sensitive. Similarly, a scraping of the base for microscopic examination for multinucleated giant cells (Tzanck test) is rapid but neither specific nor sensitive enough and may be painful.

Syphilis

Caused by infection with Treponema pallidum a syphilitic chancre is traditionally described as a solitary, painless, shallow ulcer about 1–2 cm in diameter with hard, elevated edges.24,25 However, in one study of 64 men with primary syphilis proven by darkfield microscopy, 31 (47%) had two or more ulcers, 5 (8%) had nonindurated lesions, and in 5 (8%), the borders were irregular and slightly undermined (suggesting chancroid).26 Thus, only 27 (43%) of the 64 patients had the classically described chancre of primary syphilis. Furthermore, although chancres are painless on the genitalia they may be painful if extra-genital. They are easily overlooked if on the cervix or rectum. In children younger than age 14 years, 95% of whom acquire

syphilis by being victims of sexual abuse, the diagnosis is even more difficult. Chancres are rare. In 17 (81%) of 21 such patients, condylomata lata was the cutaneous feature of the disease.27 These appear as multiple confluent moist gray-white papule. The incubation period is about 10–90 (usually about 21) days. Neither congenital nor acquired syphilis confers life-long immunity.

syphilis by being victims of sexual abuse, the diagnosis is even more difficult. Chancres are rare. In 17 (81%) of 21 such patients, condylomata lata was the cutaneous feature of the disease.27 These appear as multiple confluent moist gray-white papule. The incubation period is about 10–90 (usually about 21) days. Neither congenital nor acquired syphilis confers life-long immunity.

Chancroid

Soft chancre or chancroid is an ulcer produced by Haemophilus ducreyi. The organism is highly infectious; in experimental infection, inoculation of even one colony-forming unit (cfu) is enough to produce a papule in 50% of subjects. Pustule formation occurs in 50% of subjects at a dose of 27 cfu and in 90% with as few as 100 cfu.28 The incubation period is 3–5 days. The pathogenesis is largely unknown, although it has been demonstrated that H. ducreyi releases a cytolethal distending toxin that arrests cells in the G2 phase.29 Clinically, lesions begin as a papules or vesicles that later rupture to leave shallow, painful ulcers. Most patients have two or more soft lesions. Later, there are large ulcers in the genital area with beefy red granulation tissue and inguinal adenopathy. About 10% of persons who have chancroid acquired in the United States are coinfected with Treponema pallidum or HSV.8

Treatment failures are often related to the concomitant presence of HSV or to misdiagnosis of HSV-associated lesions as chancroid.30 Patients with HIV infection are also less likely to be cured.31 Culture of H. ducreyi requires special agar media. Newer diagnostic tests have been developed, including an enzyme immunoassay32 and a PCR, but they are not widely available.33

Donovanosis (Granuloma Inguinale)

Donovanosis is endemic to Papua New Guinea, Southeast India, Southern Africa, the Caribbean, Brazil, and among the aborigines in Australia. This distribution of disease is unique among STDs.34 Outbreaks in the United States have been described, predictably among travelers returning from areas of endemicity. Until recently, donovanosis has been attributed to infection with Calymmatobacterium granulomatis, a gram-negative bacillus.1 However, the bacterium has been reclassified as a species of Klebsiella.35 The condition is generally indolent, its pathogen is weakly infectious, and outcomes are excellent if antibiotic therapy is administered. Even so, donovanosis causes substantial morbidity and mortality, mainly because it is often not correctly diagnosed. The incubation period is usually between 1 and 12 weeks but may extend out to a year.36 Babies have presented at ages of up to 6 months with donovanosis acquired at birth.37 The lesions begin as painless nodules that erode to leave beefy red, readily bleeding, exuberant patches of granulation tissue.38 Primary lesions enlarge slowly. Secondary lesions may occur by autoinoculation. Not all cases follow the classic description; a more rapidly progressive, necrotic form has been well described. Extragenital lesions may also occur, even after the primary condition has apparently resolved. The mouth is the most commonly involved extragenital site.36 Disseminated disease is often fatal. Bone infection may occur, usually in women, who may have an undiagnosed primary cervical infection. Cervical lesions are commonly misdiagnosed as carcinomatous.39

Donovanosis can be a difficult clinical diagnosis because of its rarity, the disparity of clinical presentations, and the fastidious nature of the organism. The diagnosis usually rests upon identifying Donovan bodies inside mononuclear cells obtained from active lesions by scraping or biopsy. Nonencapsulated forms of Klebsiella granulomatis comb. nov. have a “safety pin” appearance in tissue section because of polar chromatin densities. Recently, investigators have been able to cultivate the organism in cell culture systems.40,41 PCR assays have been developed.42,43 Studies show some utility of an indirect immunofluorescence assay.44

Doxycycline is the usual treatment, but comparative trials of antimicrobial agents are lacking. One gram of azithromycin once a week for 4 weeks produced apparent clinical cure in 11 patients.45 However, relapses may occur a few months to 2 years after apparent clinical cure. Ceftriaxone, administered intramuscularly at a dose of 1 gram per day for 7–10 consecutive days, was successful at eradicating disease in a group of chronically infected aboriginal patients.46

Pemphigoid Gestationis

This bullous skin disease occurs during pregnancy. It may involve the trunk, extremities, groin, and buttocks. Previously, and regrettably still on occasion, the condition was referred to as “herpes gestationis.” It is autoimmune in nature, and therefore has nothing to do with herpes simplex virus.47 Histologically,

there is deposition of C3 along basement membranes48 and eosinophilic infiltration is prominent.49 It is thought to be similar to bullous pemphigoid; sera from 79% of women with the condition recognize the antigenic domain of the bullous pemphigoid antigen.50 There is a tendency for women with pemphigoid gestationis to develop other autoimmune conditions, especially Graves’s disease.51 Patients with this condition may also have chronic placental insufficiency, which leads to an increased frequency of preterm births and small for gestational age babies.48

there is deposition of C3 along basement membranes48 and eosinophilic infiltration is prominent.49 It is thought to be similar to bullous pemphigoid; sera from 79% of women with the condition recognize the antigenic domain of the bullous pemphigoid antigen.50 There is a tendency for women with pemphigoid gestationis to develop other autoimmune conditions, especially Graves’s disease.51 Patients with this condition may also have chronic placental insufficiency, which leads to an increased frequency of preterm births and small for gestational age babies.48

Uncommon Causes

Cutaneous tuberculosis can present with ulcerative skin lesions in the inguinal or genital area. In childhood, however, cutaneous TB usually presents as condylomata lata rather than as a chancre.52 In endemic areas, African trypanosomiasis causes genital ulcerative disease.53 A chancre secondary to nodular mucocutaneous histiocytosis has been described.54 In several patients, genital ulcerations have appeared coincidentally with infectious mononucleosis due to EBV. The ulcerations were described as having purple margins.55 Obviously, genital ulcers from some other condition could occur coincidentally with EBV infection; however, laboratory tests for other causes were negative. Adding further support to the concept that EBV could be causally related to the genital ulcerations is a report from Thailand, in which 17 (57%) of 30 HSV culture-positive genital ulcerative lesions were also positive for EBV DNA by PCR.56 Amebiasis of the glans penis is a rare cause of ulcerative disease; it should be suspected when ulcerative lesions are refractory to antibiotic therapy.57

Laboratory Approach

Culture of the lesions for HSV should be performed, but treatment for clinically suspected disease should not be delayed pending the culture result.21 Darkfield microscopic examination of material from a chancre-like ulcer may reveal the spirochetes of syphilis, but darkfield facilities with experienced observers are usually available only in clinics where the disease is frequently seen. Gram stain of the smear of the chancre-like ulcer may reveal rows and chains of gram-negative rods, characteristic of Haemophilus ducreyi. H. ducreyi is difficult to culture because it is fastidious, but new media are being developed.

Special stains of a smear from crushed tissue preparations from donovanosis typically demonstrate oval Donovan bodies.

Serologic screening tests for syphilis, such as the VDRL test, are often not yet positive at the time the syphilitic chancre first appears but usually become positive within a few weeks thereafter. The VDRL should be obtained as soon as the chancre is seen and repeated in about 2 weeks. Antisyphilitic therapy should be given as soon as the physician suspects syphilis, without waiting for the VDRL results. Early treatment of the primary chancre usually results in a negative VDRL by 1 year, and treatment of secondary syphilis usually results in VDRL seronegativity by 24 months.60

All positive VDRL results should be confirmed by specific tests, such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorbed test (FTA-ABS), because biologic false-positive VDRLs are common in adolescents. Even false-positive FTA-ABS tests can occur, so this test should not be used for screening purposes.

Treatment

Selected regimens from the 2002 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for treatment of STDs are shown in Table 15-2.8 Not all of the CDC treatment regimens are shown. Fever, malaise, and intensification of skin lesions (Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction) occur in many patients within 12 hours of the start of parenteral penicillin therapy for syphilis.

Inguinal Lymphadenopathy

Enlargement of inguinal or femoral lymph nodes can have many causes unrelated to genital diseases and in children is usually due to infections of the lower extremities. However, tender or suppurative nodes in a postpubertal person should raise the question of a genital infection.

Lymphogranuloma Venereum (LGV)

Caused by the serovars L1, L2, or L3 of Chlamydia trachomatis, this STD is rare in the United States.8 Its first manifestation is typically a tender inguinal

node (bubo). Usually the primary lesion, a small papule or erosion that occurs 1–2 weeks after exposure, is not noticed or reported, and the bubo appears 2–4 weeks after exposure. The bubo may proceed to suppuration. Associated erythema nodosum (see Chapter 17) is common.61 Its presentation may mimic psoas abscess,62 carcinoma,63 or incarcerated inguinal hernia.64 Severe, untreated cases may lead to rectovaginal fistulae65 or rectal strictures,66 raising the specter of Crohn’s disease.

node (bubo). Usually the primary lesion, a small papule or erosion that occurs 1–2 weeks after exposure, is not noticed or reported, and the bubo appears 2–4 weeks after exposure. The bubo may proceed to suppuration. Associated erythema nodosum (see Chapter 17) is common.61 Its presentation may mimic psoas abscess,62 carcinoma,63 or incarcerated inguinal hernia.64 Severe, untreated cases may lead to rectovaginal fistulae65 or rectal strictures,66 raising the specter of Crohn’s disease.

TABLE 15-2. TREATMENT OF SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED DISEASES (BASED ON 2002 CDC RECOMMENDATIONS# USING ADULT DOSAGES) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Syphilis and chancroid also may produce inguinal adenopathy, with overlooked or denied primary lesions.67 Occasionally, syphilitic inguinal adenitis, which is painless, resembles an incarcerated inguinal hernia.68 In HIV-infected patients, Mycobacterium chelonae infection of an inguinal node may produce a bubo.69

Laboratory Diagnosis

The diagnosis of LGV can be difficult. The causative agent is difficult to culture, and the L1-L3 serovars of C. trachomatis may serologically cross-react with the more common varieties. In one study of 12 patients with LGV buboes, light microscopy demonstrated intracellular organisms whose morphology was consistent with Chlamydia spp in all 12.70 A group of researchers made monoclonal antibodies against L1 and L3 serovars and developed an immunofluorescence assay for LGV. Using this test, they were able to diagnose LGV in 21 (84%) of 25 smear-negative patient samples.71 Syphilis should be excluded by a VDRL test in sexually active teenagers with inguinal adenitis.

Condylomata

Genital Warts (Condyloma Acuminata)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree