Hepatitis Syndromes

Hepatitis is injury to the liver, with or without hepatocyte necrosis, which results in an influx of acute or chronic inflammatory cells. Damage to the liver cell membrane results in release of liver enzymes into the bloodstream. Thus, from a practical standpoint, hepatitis can be broadly defined as the presumptive diagnosis when the serum aminotransferase levels are elevated. This definition remains useful, despite the following limitations. First, mild elevations are present in a small percentage of healthy persons, causing some experts to consider aminotransferase levels elevated only if they are persistently twice the upper limit of normal, especially in asymptomatic persons.1 Second, although predominantly found in hepatocytes, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and, to a lesser extent, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) are found in other tissues as well. Congestive heart failure, severe myositis, and celiac disease are some of the conditions that may cause elevation of serum aminotransferases in the absence of liver disease.2 Third, some patients with viral hepatitis do not have elevated liver enzymes, despite histologic evidence of chronic hepatitis.3,4

Although the term hepatitis is sometimes used to mean infection caused by one of the lettered hepatitis viruses, it is more useful to regard hepatitis as a syndrome of many possible etiologies.

Classification

A number of syndromes of hepatitis can be defined on the basis of the onset, severity, and course. No specific etiology should be inferred from these terms.

Acute Icteric Hepatitis

Acute icteric hepatitis is best defined as the abrupt onset of hepatocellular—not obstructive or hemolytic—jaundice. The degree of hyperbilirubinemia is variable, and fractionation is of little clinical value. The early detection of urobilinogen is helpful because it usually precedes jaundice. Fever, malaise, anorexia, and vomiting are often prodromes but are not essential to the definition. On physical examination, the liver is usually enlarged and may be tender. Typically improvement begins within a week or two. It is useful to use the etiologically neutral syndrome diagnosis of “acute hepatitis” as a preliminary diagnosis rather than “infectious hepatitis,” in order to remain alert to the possible noninfectious causes of this syndrome.

Anicteric Hepatitis

This is the most frequent form of hepatitis, especially in children, and is detected primarily by serial measurement of serum aminotransferase levels in a patient with a known exposure. The child may be entirely asymptomatic or may have only nonspecific symptoms such as fever and malaise, often leading to the diagnosis of an influenza-like illness.

Fulminant Hepatitis

Fulminant hepatitis is characterized by rapid progression to liver failure, manifested primarily by a change in consciousness progressing to coma over the course of a few days. Bleeding often occurs secondary to hepatocellular failure and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Although some children recover spontaneously, emergency liver transplantation is usually required for survival. The cause of most cases of fulminant hepatitis remains unknown, although viral infections, toxins, drugs, and autoimmune diseases are occasionally implicated.

Chronic Hepatitis

Chronic hepatitis is defined arbitrarily as hepatic injury that persists for at least 6 months, with persistently elevated bilirubin or liver enzymes in the serum.5 In the past, terms such as chronic persistent hepatitis or chronic active hepatitis were used as descriptors.

However, it is most useful to specify the etiology and histologic status, if known (e.g., chronic hepatitis B with mild fibrosis).

However, it is most useful to specify the etiology and histologic status, if known (e.g., chronic hepatitis B with mild fibrosis).

Recrudescent (Relapsing) Hepatitis

A small percentage of patients with acute viral hepatitis develop an increase in aminotransferase levels after an initial period of recovery. In one study of patients with hepatitis A virus infection, nearly 10% developed this biphasic pattern, some of whom were symptomatic during the second phase.6 In hepatitis C virus infection, repeated episodes of recrudescence are usually a harbinger of chronic infection.7 Occasionally, an apparent recrudescence in a high-risk patient is the result of new infection with a different hepatitis virus.

Hepatitis During Pregnancy

Hepatitis occurring during pregnancy is important because of increased severity (particularly with hepatitis E virus infection) and because of the risk of transmission of infection to the fetus (especially with hepatitis B virus infection and to a lesser extent with hepatitis C virus infection).8 Maternal–fetal transmission is discussed in the section on prevention.

Neonatal Hepatitis

In the first month of life, hepatitis with an infectious cause is often a congenital infection and is discussed in Chapter 19.

Perihepatitis

The Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome complicating gonorrhea or Chlamydia trachomatis infection is associated with liver tenderness but not with significant elevation of liver enzymes. Therefore, it does not meet this chapter’s definition of hepatitis.

Granulomatous Hepatitis

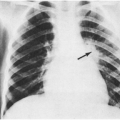

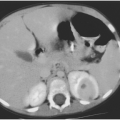

Many systemic disorders, infectious and noninfectious, can produce hepatic granulomas,9 which is a more appropriate term than granulomatous hepatitis because the liver enzymes are usually normal. Patients often present with fever of unknown origin, and the granulomas are usually diagnosed by ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) of the liver. In children from an area of high endemicity, cat-scratch disease is now recognized as a relatively common cause of hepatic granulomas.10 There may be splenic involvement as well, and abdominal pain may be a presenting symptom.11 Other causes of hepatic granulomas include tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, sarcoidosis, chronic granulomatous disease, and reactions to certain drugs.

Reactive Hepatitis

Many systemic infections are associated with focal liver injury and elevated serum aminotransferase levels. These are discussed in the subsequent section on Other Infectious Causes. Because it is often clinically difficult to differentiate between a reactive hepatitis and hepatitis caused by a hepatotropic virus, the distinction is not usually made until an etiologic diagnosis is apparent. When encountering a patient with hepatitis and systemic findings, it is best to describe them both (e.g., acute icteric hepatitis in a patient with exudative pharyngitis).

Lettered Causes of Hepatitis

Although many infections can cause hepatitis, the lettered hepatitis viruses have particular tropism for the liver and are discussed separately. Table 13-1 gives an explanation of common abbreviations associated with these viruses, and Table 13-2 summarizes their major characteristics.

Hepatitis A Virus

Most cases of hepatitis A result from person-to-person transmission by the fecal-oral route during prolonged communitywide outbreaks.12 Children in day-care centers play an important role in transmitting infection to adult contacts.13 Infection may also be acquired during foreign travel or as part of a common-source food borne outbreak.14 About half of cases have no recognized source.

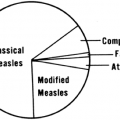

The spectrum of clinical illnesses produced by hepatitis A virus has been well described on the basis of experimental volunteer studies and outbreaks. A landmark article describing the differences between hepatitis A and B was published in 1967.15 In children younger than 6 years of age, most infections are asymptomatic. If illness does occur, jaundice is usually absent. In contrast, older children and adults usually present with acute icteric hepatitis. About 1 month after exposure, the patient with this form of hepatitis A develops high fever, sweating, shaking chills, myalgia, severe anorexia, nausea, and possibly vomiting. Occasionally,

a mono-like illness with or without atypical lymphocytes may occur.16 An enlarged, tender liver is palpable, but jaundice and bile in the urine may not be noted for several days. The maximum serum aminotransferase concentration usually occurs about 2 days after the onset of illness. Symptoms usually resolve by 2 months, but some patients have one or more relapses. Fulminant hepatic failure is very uncommon.17,18

a mono-like illness with or without atypical lymphocytes may occur.16 An enlarged, tender liver is palpable, but jaundice and bile in the urine may not be noted for several days. The maximum serum aminotransferase concentration usually occurs about 2 days after the onset of illness. Symptoms usually resolve by 2 months, but some patients have one or more relapses. Fulminant hepatic failure is very uncommon.17,18

TABLE 13-1. TERMINOLOGY OF LETTERED HEPATITIS VIRUSES | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 13-2. FEATURES OF LETTERED HEPATITIS VIRUSES | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Patients are most contagious during the 2-week period before the onset of jaundice or elevation of liver enzymes, when the concentration of virus in the stool is highest.19 Viral excretion then declines and is usually absent within 1 week after jaundice appears.20 Occasionally, the virus may be shed for several months, especially in infants and young children.21 Viral shedding can also recur in patients with relapsing illness.22

Hepatitis B Virus

Unlike hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus (HBV) is not transmitted fecal-orally and is not associated with common-source outbreaks. In areas of the world with a high prevalence of hepatitis B infection, such as Asia and Africa, most infections are acquired vertically at the time of birth. In contrast, the majority of hepatitis B infections in developed countries result from sexual activity, injection-drug use, or occupational exposure.4 Because of donor screening, the risk of hepatitis B infection from a single blood transfusion is estimated to be 1 in 63,000.23 Importantly, no clear risk factors for infection are found in 20–30% of patients.4

Clinical symptoms and course depend on the age of the patient. Hepatitis B virus is not cytopathic; the host immune response is the cause of the liver injury.23a A vigorous immune response, as seen in older children and adults, results in symptomatic infection and high likelihood of viral clearance. In contrast, because of their immature immune system, more than 90% of infected neonates have an asymptomatic infection followed by chronic hepatitis. Up to 25% of persons with chronic infection eventually die of end-stage liver disease or hepatocellular carcinoma.24

In the older child, hepatitis B infection clinically resembles hepatitis A, although symptoms are usually milder. Occasionally, an acute polyarthritis and urticarial rash may precede the jaundice. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, also called papular acrodermatitis of childhood, is an erythematous papular rash sometimes seen in the child with acute hepatitis B infection. It is thought to result from deposition of immune complexes. Other viral infections such as Epstein-Barr virus, coxsackievirus, and parainfluenza virus can produce an identical rash (see Chapter 11).25,26

Hepatitis C Virus

This virus was identified in the late 1980s as the cause of most transfusion-associated “non-A, non-B” hepatitis. Currently, nearly 2% of the U.S. population

is chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), leading to its label as the “silent epidemic.”27 HCV-associated end-stage liver disease is the most frequent indication for liver transplantation in adults. With the widespread implementation of blood product screening in 1992, the current risk of transfusion-associated hepatitis C is estimated at 1 in 100,000 units.23 The virus can also be transmitted perinatally, sexually, and by injection drug use. Approximately 5% of neonates born to HCV-positive mothers become infected; if the mother also has HIV infection, the risk is 2–3 times higher.28 Sexual activity appears to be a relatively inefficient means of transmission. Long-term spouses of patients with chronic HCV infection have a prevalence of infection of less than 5%.29,30 In approximately 10% of people with hepatitis C infection, no source can be identified.28

is chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), leading to its label as the “silent epidemic.”27 HCV-associated end-stage liver disease is the most frequent indication for liver transplantation in adults. With the widespread implementation of blood product screening in 1992, the current risk of transfusion-associated hepatitis C is estimated at 1 in 100,000 units.23 The virus can also be transmitted perinatally, sexually, and by injection drug use. Approximately 5% of neonates born to HCV-positive mothers become infected; if the mother also has HIV infection, the risk is 2–3 times higher.28 Sexual activity appears to be a relatively inefficient means of transmission. Long-term spouses of patients with chronic HCV infection have a prevalence of infection of less than 5%.29,30 In approximately 10% of people with hepatitis C infection, no source can be identified.28

Most acute infections with HCV are inapparent; fewer than a third of patients will have jaundice, which may be accompanied by anorexia, malaise, or abdominal pain. As with hepatitis A and B infection, a fulminant presentation with acute hepatitis C infection is rare but has been reported in children.31 The hallmark of hepatitis C infection is its chronicity; approximately 80% of infected people develop chronic infection, which is often asymptomatic and without abnormalities in liver enzymes. For this reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has made recommendations for routine screening of people in high-risk categories.28 These include people with a history of injection-drug use, long-term hemodialysis, persistently elevated ALT levels, and those who received blood products or an organ transplant prior to July 1992.28 In addition, children born to women known to be HCV-positive should be tested for the presence of HCV antibody at 15–18 months of age, when passively transferred maternal antibody is no longer detectable.

The natural history of hepatitis C infection in children is largely unknown. Of 67 infants with transfusion-acquired infection, only 55% had evidence of chronic infection 20 years later, a figure substantially lower than is usually seen in adults.32 In addition, only three patients had histologic evidence of progressive liver disease. The majority of neonates who acquire hepatitis C perinatally develop chronic infection with only mild liver disease during childhood, although long-term follow-up data are lacking.33 In adults with chronic hepatitis C infection, 15–20% eventually develop end-stage liver disease.34 Once cirrhosis is established, the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma is approximately 1% to 4% per year.35

Hepatitis D Virus

Also called delta virus, this is a defective RNA virus that needs the help of the hepatitis B virus to replicate. Thus, it is seen exclusively in patients acutely or chronically infected with hepatitis B. Most infections occur in injection-drug users. Coinfection with hepatitis D virus (HDV) considerably worsens the prognosis of HBV infection. Therefore, hepatitis D coinfection is an important consideration when the condition of a patient with chronic hepatitis B infection worsens or when a test for HBeAg is negative but active liver disease persists.4

Hepatitis E Virus

Previously known as enterically transmitted “non-A, non-B” hepatitis, hepatitis E virus (HEV) shares many similarities with hepatitis A, including route of transmission, epidemic potential, increased incidence in the developing world, and lack of a chronic carrier state. The disease was first recognized in the early 1980s when sera from persons affected during a 1955 waterborne epidemic of hepatitis in Delhi, India, were found to lack serological markers of acute hepatitis A and B.36 The genome was cloned and sequenced in the early 1990s.37,38

Large, waterborne outbreaks have been reported from southeast and central Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Mexico.39 In contrast to hepatitis A, person-to-person transmission is uncommon. Women infected with HEV during the third trimester of pregnancy may transmit infection to their fetuses, with significant perinatal morbidity and mortality.40 The majority of clinically apparent infections occur in young adults; most infected children are probably asymptomatic.41 Symptomatic infection is indistinguishable from acute icteric hepatitis of other causes. A notable exception is that infection in pregnant women often causes fulminant hepatic failure, with mortality rates of 15–25%.42

Hepatitis G Virus

This virus, also referred to as hepatitis GB virus C, has been detected in the serum of 1–2% of healthy blood donors and can be transmitted by transfusion.43 However, there is no evidence that it causes hepatitis.44 As with the elusive hepatitis F virus,45 its

inclusion in the group of lettered hepatitis viruses was probably premature.

inclusion in the group of lettered hepatitis viruses was probably premature.

Frequency in Children

Of the lettered hepatitis viruses, hepatitis A virus is the most frequent cause of hepatitis in children in the United States.45a The incidence varies by race and ethnicity, with the highest rates occurring among American Indians/Alaskan Natives and Hispanics.46 Hepatitis B virus infection is much less common and is usually secondary to transmission during delivery. With the implementation of routine screening of pregnant women and postexposure prophylaxis of newborns with hepatitis B vaccine and hepatitis B immune globulin (see section on Prevention), the incidence of hepatitis B in children continues to decline.47 Among all age groups, the prevalence of chronic hepatitis C infection in the United States is approximately twice that of hepatitis B.35 In children, the seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus infection is 0.2% for those younger than 12 years of age and 0.4% for those 12–19 years of age,48 although rates are highly variable among population subgroups. Hepatitis in children in the United States is frequently caused by agents other than the lettered hepatitis viruses.

Other Infectious Causes

Many viruses can produce hepatitis in children, especially Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (see Chapter 3). Nonviral infections can also cause hepatitis (Box 13-1). Most of these infections are discussed in other chapters and so are only mentioned here.

Bacterial sepsis can cause jaundice (especially in the newborn) by several mechanisms, including hemolysis and liver cell destruction, and the serum aminotransferase concentrations can be significantly elevated at the onset of jaundice.49 Hepatitis with jaundice is an occasional complication of urinary infection,50 scarlet fever,51 or Kawasaki disease.52,53 Acute suppurative cholangitis and, less frequently, acute cholecystitis may be associated with elevated bilirubin and aminotransferase levels in the serum.54

Common Viruses

EBV can present with hyperbilirubinemia55 or as anicteric hepatitis.56 Fulminant hepatitis is rare.57 There is some evidence to suggest that EBV infection can induce autoimmune hepatitis in susceptible individuals.58 In addition to EBV, disseminated infection by other members of the herpes virus family (herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, human herpes virus 6) typically involves the liver, with the severity primarily dependent on the immune status of the patient.59,60,61,62,63,64 Hepatic involvement in patients with primary HIV infection is not uncommon; 20% of patients with the acute retroviral syndrome will have elevated liver enzymes.65

BOX 13-1 Some Infectious Causes of Hepatitis in Children Other than the Lettered Hepatits Viruses

| Viruses Epstein-Barr virus56 Enteroviruses (coxsackieviruses, echoviruses)70 Human immunodeficiency virus65 Adenoviruses (immunocompromised host)76 Disseminated herpes simplex,59 varicella,61 cytomegalovirus63 |

| Bacterial infections Scarlet fever51 Urinary tract infections, especially in neonates50 Liver abscesses132 Cholangitis54 |

| Uncommon infections Psittacosis (pneumonia)133 Leptospirosis79 Brucellosis (FUO)134 Rocky Mountain spotted fever (rash)135 Ehrlichiosis (cytopenia)136 Early syphilis137 Cat-scratch disease (FUO)10 Mycoplasma (pneumonia)138 Lyme disease139 Visceral larva migrans140 |

| Usually acquired outside the United States Yellow fever (and other viral hemorrhagic fevers)141,142 Amebic liver abscess143 Schistosomiasis144 Liver flukes145 Hydatid disease146 Malaria147 Typhoid fever148 Dengue fever149 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree