Urinary Syndromes

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common bacterial infections in children, affecting approximately 8% of girls and 2% of boys in the first 6 years of life.1 The exact prevalence depends on multiple factors, including age, sex, race, presence of fever, and, for boys, whether the child is circumcised. Among febrile infants in the first 3 months of life, the likelihood of UTI is approximately 13% for girls, 2% for circumcised boys, and 19% for uncircumcised boys.2 Among children less than 1 year old with fever, the prevalence is about 6% for girls and 3% for boys. Between 1 and 2 years of age, the prevalence in girls is 8%, and in boys it is 2%.3

The symptoms of UTI are commonly nonspecific, especially in infants and toddlers. Unfortunately, testing for UTI in the febrile child is often omitted. When testing is performed, results of urinalysis and culture may be misinterpreted. Despite its frequency, many controversies regarding the diagnosis and management of UTI persist. Most clinicians can agree on basic definitions.

Definitions

A presumptive diagnosis of UTI can be made on the basis of typical clinical manifestations and pyuria, but a laboratory-confirmed diagnosis depends on the demonstration of significant bacteriuria. These three characteristics need further definition.

Clinical Manifestations

The manifestations of UTI vary greatly depending on the patient’s age. In adults and adolescents with a urinary infection, high fever (>103°F; 39.5°C) usually indicates renal involvement. Children may occasionally have high fever without renal involvement, although reflux with renal infection should be suspected.4 Frequent or urgent urination implies urethral or bladder irritation. Cloudy urine may be caused by bacterial growth but may also result from precipitated solutes. Foul-smelling urine implies bacterial growth, but occasionally the parent regards concentrated urine as foul smelling. Suprapubic pain or tenderness implies infection involving the bladder; flank pain or tenderness implies infection involving the kidney. Vomiting and other gastrointestinal symptoms not suggesting the urinary tract may be present.

In infants, symptoms are more likely to be absent, mild, or not referable to the urinary tract. Fever may be the only symptom. It is the infant group for whom it is most important, and also most difficult, to diagnose a UTI. The distinction between cystitis and pyelonephritis is particularly difficult in this age group. Among febrile children less than 24 months old with UTI, approximately 60% are found to have renal involvement by scintigraphy.5,6,7

Although peripheral white blood cell (WBC) count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein tend to be higher in children with renal involvement,8 these markers are not specific for pyelonephritis. Asymptomatic infections are also not rare in females and are detected in about 1% of school-aged girls. True asymptomatic bacteriuria is probably not a risk factor for adverse sequelae in this population.9 However, in reality, some girls with recurrent UTI have subtle symptoms, often the same with each infection, which should not be considered “asymptomatic bacteriuria.”

Pyuria

Generally, “pyuria” is defined as more than 5 (or 10) leukocytes per high-power field in the centrifuged sediment or as an elevated leukocyte count in the uncentrifuged urine, using a hemocytometer to determine the count rapidly.10 Most authorities agree that 10 or more leukocytes per microliter, as counted on a hemocytometer, represents pyuria. (Centrifuging helps by concentrating the findings of dilute urine and adding the potential for observation of other formed elements.) There is no widely accepted definition of “pyuria,” so that the upper

limit of normal for leukocytes in the urine is defined by the laboratory or by the physician doing the examination and depends on the methods used. Usually, however, the number of leukocytes in the urine is clearly more than normal, and there is no question about the presence of pyuria. A recent meta-analysis of 48 studies defined “pyuria” as 10 WBC or greater per high-powered field of centrifuged urine or 10 WBC or greater per μl of unspun urine.11

limit of normal for leukocytes in the urine is defined by the laboratory or by the physician doing the examination and depends on the methods used. Usually, however, the number of leukocytes in the urine is clearly more than normal, and there is no question about the presence of pyuria. A recent meta-analysis of 48 studies defined “pyuria” as 10 WBC or greater per high-powered field of centrifuged urine or 10 WBC or greater per μl of unspun urine.11

Clumps or casts of WBCs also indicate pyuria. The detection of pyuria (or its absence) is extremely helpful in assessing the likelihood of UTI, with a sensitivity of 80–90% and a specificity of 90–95%.8,12 This does not imply that a culture is unnecessary—it demonstrates that pyuria can help with interpretation of the culture results. In a population with an overall prevalence of UTI of 5% (e.g., infants and young children who have fever without localizing signs), the absence of pyuria predicts the absence of a UTI with greater than 99% accuracy (negative predictive value). The presence of pyuria in this population predicts the presence of UTI in approximately 50% (positive predictive value). The presence of pyuria and microscopic bacteriuria (discussed later) increases the positive predictive value to 85%.8 The leukocyte esterase test is a surrogate for the presence of WBCs. Its sensitivity and specificity are both about 80%. In contrast, the nitrite reaction is highly specific (approx. 98%) but lacks sensitivity (approx. 50%).3

Bacteriuria

Microscopic

Microscopic examination for pyuria is also useful for immediate recognition of the presence of bacteria, which correlates well with the results of urine culture.10,13 Although the absence of bacteria in the centrifuged sediment does not exclude urinary infection, especially with cocci, bacteria can usually be seen in the sediment if the culture is going to result in more than 100,000 bacteria/mL. Bacteria in casts indicate pyelonephritis. A methylene blue or Gram stain of a drop of uncentrifuged urine is a slightly more sensitive test for microscopic bacteriuria.13

Controlled studies have repeatedly demonstrated the usefulness of these methods, which have a sensitivity of 80–90% for unstained centrifuged urine, 85–94% for stained uncentrifuged urine, and 87–98% for stained centrifuged urine, depending on the number of bacteria designated significant in the microscopic study (1 or 5 or 10/hpf) and using 100,000 colonies/mL as the standard culture criterion for significance.13 Obviously, some significant cultures are not predicted by these methods. Most experts regard any bacteria visualized as being significant, especially if a gram-negative rod is seen.11,14

Microscopic bacteriuria with a negative culture can have several possible explanations. Most frequently, the bacteria seen are contaminants that are not recovered by the usual bacteriologic media, for example, diphtheroids, vaginal lactobacilli, or Haemophilus spp.15 However, artifacts and technical errors in collection and culture are much more likely explanations than failure to grow a fastidious pathogen.16,17

Significant Bacterial Growth

This term indicates that a properly collected urine culture has had a quantitative culture (“colony count”). Kass found that more than 100,000 bacteria/mL in a clean voided urine usually indicates urinary infection.17a The difficulties of this figure do not lie with the accuracy of the counting, which is well within the capabilities of office bacteriology, using a quantitative loop, but rather with the collection of the specimen. The value of more than 100,000 bacteria/mL should not be taken as absolutely reliable in itself, because it assumes a clean voided urine.

Specimens obtained by catheter or suprapubic puncture are significant for infection at a lower concentration. Many experts consider any pure growth from a suprapubic puncture to be significant. Specimens obtained by catheter are subject to a greater risk of contamination by periurethral skin flora (about 9% contamination rate) than suprapubic puncture, and a higher cutoff is appropriate. Hoberman et al.14 obtained 3257 catheterized urine specimens from young febrile children and found that counts less than 50,000 per mL were most likely to be associated with nonpathogens, mixed flora, or the absence of pyuria. Accordingly, they recommend greater than 50,000 organisms per mL as the cutoff for significant growth from a catheterized specimen.

Interpretation of urine cultures requires that multiple factors be taken into consideration. For example, in a young febrile child without another apparent source for the fever, pure growth of a common

urinary pathogen at less than 50,000 organisms per mL from a catheterized specimen may be significant, particularly if the urinalysis shows pyuria. On the other hand, growth of 50,000 to 100,000 organisms per mL is unlikely to indicate a UTI if there is another apparent cause of fever (such as a viral illness), if the organism does not commonly cause UTI (such as Staphylococcus aureus), if multiple organisms grow in culture (indicating a contaminated specimen), or if there is no pyuria.

urinary pathogen at less than 50,000 organisms per mL from a catheterized specimen may be significant, particularly if the urinalysis shows pyuria. On the other hand, growth of 50,000 to 100,000 organisms per mL is unlikely to indicate a UTI if there is another apparent cause of fever (such as a viral illness), if the organism does not commonly cause UTI (such as Staphylococcus aureus), if multiple organisms grow in culture (indicating a contaminated specimen), or if there is no pyuria.

Logical Classification

Using the three factors—clinical manifestations, pyuria, and significant bacteriuria—it is possible to classify any patient into one of eight logical possibilities of combinations (Table 14-1). The use of such a preliminary diagnostic category aids the clinician by giving a guide to an anatomic diagnosis. The logical preliminary diagnoses can have a number of possible etiologies. Typical urinary infection means that all three features (clinical findings, pyuria, and significant bacteriuria) are present.

Urinary symptoms without pyuria or bacteriuria should be the preliminary diagnosis when there are signs and symptoms suggesting a UTI but no pyuria or significant bacteriuria. There are several possible causes of this pattern. Urethritis or vaginitis, especially that caused by Chlamydia (discussed in Chapter 15), is a common cause. Infection with Ureaplasma urealyticum (and possibly Mycoplasma hominis) may cause these symptoms, especially in adults.18

Recent or current antibiotic therapy that has suppressed culture-confirmation of the infection is one of the most frequent causes. Overhydration, with rapid urine flow and frequent voiding before bacteria can reach high concentrations, is a rare cause.19 Medications, such as atropine-like drugs, are an occasional cause of transient frequent urination. Unilateral pyelonephritis with complete ureteral obstruction can produce unusual or intermittent urinary abnormalities.

TABLE 14-1. LOGICAL COMBINATIONS OF THREE MAJOR VARIABLES IN URINARY INFECTONS* | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Urinary symptoms and pyuria without bacteriuria is probably most frequently caused by urethritis. The urethral syndrome (dysuria-pyuria syndrome) can do this and is discussed later in this chapter. Gonorrhea and nongonococcal urethritis are discussed in Chapter 15. Fastidious or anaerobic organisms causing a bladder or kidney infection are an uncommon cause of this pattern.16 However, Haemophilus influenzae is an example of an organism that will not grow on the plating media usually used for urine and that should be regarded as a rare cause of this pattern, usually only in association with clinically suspected bacteremia.17 Suppression of bacterial growth by contamination of the urine with the disinfectant used to prepare the urethral area is also a very unlikely cause.

Adenoviral cystitis is an uncommon cause of microscopic hematuria and pyuria without bacteriuria.20

M. hominis has been implicated in kidney infections in adults by antibody studies.21 Ureaplasma urealyticum can cause a urethritis even in prepubertal children.22 Gardnerella vaginalis is an uncommon urinary pathogen.23

Campylobacter jejuni, which requires special

media and higher incubator temperatures to grow, can be missed if it is not suspected, as in a Gram stain. It has been reported as a cause of urinary infection in a girl who did not have any recent diarrhea, as might have been expected.24

media and higher incubator temperatures to grow, can be missed if it is not suspected, as in a Gram stain. It has been reported as a cause of urinary infection in a girl who did not have any recent diarrhea, as might have been expected.24

Urinary symptoms and bacteriuria without pyuria is uncommon. The specimen may have been obtained very early on, before the development of an inflammatory response (as manifested by pyuria) could develop. Alternatively, symptoms may not occur until several days after the onset of an infection when pyuria has decreased. The urinalysis and culture should be repeated to clarify the situation, if an antibiotic has not been given that would be likely to eradicate the bacteriuria.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria and pyuria can be a manifestation of a urinary infection where signs and symptoms are suppressed by recent or current antibiotic therapy. It may also be attributable to poor technique in collecting voided urine when there is no true infection. This is especially likely if there is vaginitis, or if the patient is an uncircumcised male, or if there is a delay in inoculation of the culture media.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria without pyuria can have several causes. The most common reason is bacterial contamination of the urine specimen. Uncommonly, it may be seen early in an infection (before an inflammatory response occurs) or late in an infection (after the initial clinical manifestations and pyuria have disappeared). Rarely, it follows suppression of symptoms and pyuria by inadequate chemotherapy. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is not uncommon, especially in young girls, as discussed in the introduction section of this chapter.

Asymptomatic pyuria without bacteriuria has many possible causes, including several infectious ones.25 A bacterial urinary infection suppressed by antimicrobial therapy may produce this pattern. Cystitis secondary to gram-positive bacteria is another possible cause. Urethritis can be gonococcal, nonspecific, or chemical, as discussed later. Renal tuberculosis should also be considered in the appropriate setting.

Poor urine collection, as mentioned previously, is a possible cause. Pyuria without infection often occurs after urethral instrumentation or bladder surgery.26 Noninfectious subacute or chronic renal disease can be associated with pyuria, but proteinuria, casts, or hematuria are often present. Fever in a patient with chronic renal disease may stimulate pyuria. Pyuria is also observed during convalescence from acute glomerulonephritis or toxic nephritis, but some hematuria is also usually present. Kawasaki disease is frequently associated with a sterile pyuria. Extreme dehydration can also produce pyuria. Patients with medication-induced interstitial nephritis may have pyuria, especially with eosinophils.

No bacterial urinary infection is a secure diagnosis if all three variables are negative, provided that there has been no recent antibiotic therapy.

Risk Factors

The rate of UTI in uncircumcised males is approximately 5–10 times higher than in circumcised males.27,28 The incidence of UTI is higher in white children than in black children. The likelihood of UTI increases with increased height and duration of fever. UTI is less likely if there is another possible explanation for the fever (such as a viral exanthem).14,29

Any anatomic or functional abnormality that inhibits the ability to empty the bladder completely will predispose to UTI. Examples include neurogenic bladder in patients with myelomeningocele; obstruction from stones, tumors, or constipation; congenital defects (such as ureteral stenosis or posterior urethral valves in boys); and purposefully infrequent voiding. Indwelling urinary catheters are also a risk for infection, as discussed later.

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) refers to the retrograde flow of urine from the bladder into the upper urinary tract. It is present in about 1% of children and is a predisposing factor for pyelonephritis in children with bladder infection.30 VUR is present in 25–40% of children with acute pyelonephritis.31 As mentioned, among young children with UTI, about 60% have evidence of renal involvement by scintigraphy; thus, about 15–25% of children with UTI will have VUR. The degree of reflux is graded from I to V based on results of voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG). Grade I indicates reflux to the proximal ureter, Grade II indicates reflux to the renal pelvis without dilation, and Grades III, IV, and V indicate mild, moderate, and severe ureteral and calyceal dilation, respectively. The management of VUR is discussed later in this chapter.

Routine Screening of Healthy Children

Although the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a screening urinalysis at the age of 5

years,32 the practice of obtaining urinalyses on children at well-child visits is controversial. Among preschool-aged children, the rate of asymptomatic bacteriuria is about 1% in girls and 0.03% in boys. There are currently no data to suggest that detection of and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria prevents subsequent pyelonephritis or renal scarring. Routine screening is costly and results in follow-up testing and imaging in a large percentage of healthy children with false-positive tests.33

years,32 the practice of obtaining urinalyses on children at well-child visits is controversial. Among preschool-aged children, the rate of asymptomatic bacteriuria is about 1% in girls and 0.03% in boys. There are currently no data to suggest that detection of and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria prevents subsequent pyelonephritis or renal scarring. Routine screening is costly and results in follow-up testing and imaging in a large percentage of healthy children with false-positive tests.33

Intermittent screening for UTI may be appropriate for the child at particular risk (such as those with neurogenic bladder). In addition, a low threshold for obtaining a urinalysis and culture should be maintained in the child with a previous history of UTI who has symptoms, however mild, that suggest the possibility of recurrent infection.

Some nephrologists believe that a screening urinalysis (without culture) by laboratory methods or even by “dipstick” at ages 5 and 12 years may be helpful in the early diagnosis of certain glomerulonephritides.

Collection and Culture of Urine

Methods

The bacteriologic confirmation of urinary tract infection is only as accurate as the method of urine collection and several variables involved in its culture. In school-aged children, the physician should proceed from simple to more complicated methods of urine collection and use the least painful method appropriate for the clinical situation. In children who cannot cooperate well, or in infants or children who are not toilet trained and cannot produce a reliable specimen, the clinician should not proceed with antibiotic therapy without a specimen obtained for culture by a highly reliable method. Uncertainty about the validity of the diagnosis because of a poorly collected urine sample may lead to a decision for radiographic evaluations to avoid missing a correctable defect when there would have been no basis for expensive and uncomfortable procedures if the urine had been collected properly.

Random Voided Bag Specimens

This method may be used to obtain a urinalysis when looking for the presence of proteinuria, glycosuria, or pyuria. It may also be used to detect cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in the young infant. However, it is of no value for performing a bacterial urine culture because of the high rate of contamination. A large study (7584 cultures) revealed a contamination rate of 63% when bag specimens were cultured versus only 9% in catheterized specimens. Uncertainty regarding culture results led to unnecessary recall, treatment, radiologic investigations, and even hospital admission for some infants.34 The problem with bag specimens is that the culture generally reflects the bacteria present on the skin of the periurethral area. In one study of 98 children, a periurethral culture was obtained, followed immediately by a bag urine culture. In 20 (95%) of 21 urine cultures that contained a pathogen, the same organism was isolated from the periurethral swab culture.35 Assuming a 5% prevalence of UTI, the positive predictive value of a bag urine specimen is 15% (that is, 85% of positive cultures are false-positive). If the prevalence of UTI is 2% (febrile boys), the false-positive rate is 93%; if the prevalence is 0.2% (circumcised boys), the false-positive rate is 99%.3

Bag specimens are only useful if they are culture-negative. Unfortunately, they are so often positive that it is hard to justify their use.

Midstream Specimens

Midstream specimens are readily obtainable from cooperative toilet-trained children.36,37 In one study of girls 2–12 years of age, there was a 97% correlation between culture results of a midstream clean-voided specimen and a simultaneous catheter specimen.36 In older girls, a plastic device to spread the labia may be useful.38 However, in actual practice, unless the office or clinic staff is very experienced and supervises the urine collection, the “clean catch” midstream urine might more accurately be called the “dirty catch” specimen.19

The above comments apply to girls. For toilet-trained boys who produced a midstream specimen, 5–10% had low colony counts and obvious contaminants, but cleaning the meatus with soap actually resulted in a higher contamination rate (10%) than when the same boys were not cleaned before the collection (5%).39 Similar studies in women have shown that the contamination rate is the same whether they are instructed to clean first, or whether they are simply told to urinate into a cup.40

So-called midstream, or clean-catch, specimens can also be obtained in infants or neonates, but the technique requires extreme patience. The infant is

held over a sterile collection device and then given oral fluids. This results in fairly reliable specimens, even when performed by parents.41 In a study of 50 circumcised males who served as their own controls, the midstream collection technique was just as reliable as suprapubic bladder aspiration.42

held over a sterile collection device and then given oral fluids. This results in fairly reliable specimens, even when performed by parents.41 In a study of 50 circumcised males who served as their own controls, the midstream collection technique was just as reliable as suprapubic bladder aspiration.42

Catheterization

Young children who are not toilet trained and for whom the diagnosis of UTI is being considered should generally undergo bladder catheterization. In addition to culture results, catheterization can provide additional useful information. Bladder catheterization is essential to determine residual urine, which may be useful for evaluation of patients with recurrent urinary infection. Often, the determination of residual urine can be combined with obtaining a specimen for culture. The child should be allowed to void without anxiety under comfortable conditions, so maximum emptying is likely. Then, the catheterization is done. This catheterization can also be used in preparation for a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG), thus doing only one catheterization for the three procedures.

For patients in whom a first UTI is suspected, the specificity of a catheterized specimen can be increased by discarding the first few drops of urine and then collecting the specimen for culture. Practically speaking, however, there is often not enough specimen to allow for any wastage, especially in neonates, who often urinate just as catheterization is about to be performed or who urinate “around” a too-small catheter. Anecdotally, if the person doing the catheterization is prepared to catch urine in a sterile cup in case the patient urinates prior to catheterization, the results are usually reliable.

When catheterization is done for relief of obstruction, the urine should be cultured. Likewise, when catheterization is done for severe acute illnesses, such as in a child hospitalized because of diabetic acidosis, the urine should be cultured.

Catheterization should not be regarded as a dangerous procedure; the risk of introducing infection is extremely low.43 In one study of children with myelomeningocele, children who underwent clean intermittent catheterization starting in the first year of life (mean age of 7 months) had improved long-term renal function compared with children in whom catheterization was started after age 3 years (mean age 44 months).44 Complications of urinary catheterization were not seen.

Suprapubic Aspiration (Bladder Puncture)

Still considered the gold standard by some physicians, suprapubic aspiration has generally fallen out of favor in clinical practice, mainly because of the desire to be as noninvasive as possible, but also because of the frequency of “dry taps.” The following three conditions45 are indications for bladder puncture:

Inability to get a clean-voided midstream specimen, usually related to the patient’s inability to cooperate, as in a newborn, small child, or comatose patient;

Urgency of the specimen, as when a patient has a severe illness and information about urine must be obtained immediately (e.g., suspected septicemia); and

Urethral catheterization undesirable or impractical, as when vaginitis, urethritis, a tiny urethra, or meatal disease is present.

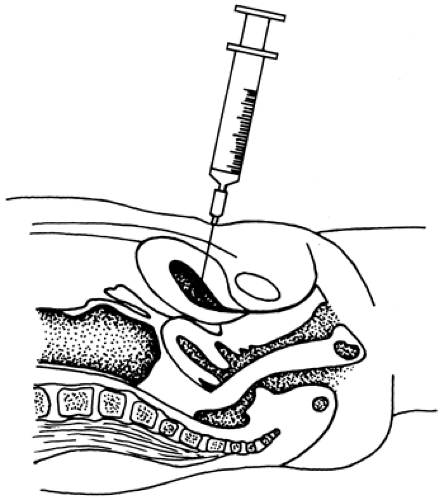

If these three conditions are not met, catheterization is the preferred method for obtaining urine for culture. Contraindications to suprapubic bladder aspiration include any bleeding problem and recent voiding that has resulted in an empty bladder. If the procedure is done on an infant or small child, the patient should be immobilized in a supine position. After cleaning and disinfecting the suprapubic area, the urethra is compressed with a gloved finger to prevent spontaneous voiding while a 10-mL syringe with a 22-gauge needle is quickly inserted perpendicular to the table (Fig. 14-1). Gentle suction should aspirate urine, although failure to obtain urine is not rare. In some studies, greater than 50% of aspirates failed to obtain urine.3

Success of the procedure depends upon the amount of urine in the bladder; therefore, it is least likely to be successful in a baby who is quite ill and, therefore, dehydrated. In one study, unsuccessful suprapubic aspirations were followed by successful catheterizations in all 27 cases.46 Some gross hematuria occasionally is noted on the next spontaneous voiding. Puncture of the bowel is rare.

Considerations in Diagnosing UTI

Recent or Current Antimicrobial Therapy

Antimicrobial therapy can inhibit bacterial growth in the bladder, so that colony counts will be below 100,000/mL. No prospective studies have been done to define precisely the length of time antimicrobial

therapy must be stopped in order to allow bacterial growth. In general, 48 hours appears to be reasonable on the basis of clinical experience with this interval,37 although longer would, of course, be better.

therapy must be stopped in order to allow bacterial growth. In general, 48 hours appears to be reasonable on the basis of clinical experience with this interval,37 although longer would, of course, be better.

Concentration of Urine and Frequency of Voiding

The lowest concentrations of bacteria in the urine occur in the late afternoon and the highest concentrations in the early morning, presumably because of concentration of the urine. However, this finding may also be a function of infrequent voiding through the night, because frequent voiding reduces bacterial concentrations in the urine.

Delay Before Inoculation

If there must be a delay in inoculation, refrigeration of the urine specimen is appropriate to inhibit multiplication of bacteria, but the value of this depends on urine pH and the species of the organism. For example, enterococci that are causing an infection may produce low colony counts (fewer than 40,000 organisms/mL) because they grow so poorly in acid urine.

Skin Flora

Staphylococcus epidermidis is a cause of urinary infection in children in rare cases, so it should not automatically be regarded as a contaminant when reported as a pure growth in concentrations exceeding 100,000/mL.

Staphylococcus saprophyticus is a coagulase-negative staphylococcus that is distinguished from S. epidermidis primarily by the former’s resistance to the obsolete antibiotic novobiocin. S. saprophyticus is an important cause of UTI in adolescent girls and young women that is temporally related to sexual intercourse.47

Office Tests

A number of chemical screening tests have been studied for use in the physician’s office for detection of urinary infections without the delay and problems of culture. Many of these have been found unsatisfactory after an initial period of enthusiasm. Two methods have been used to simplify culturing.

Quantitative Loop

This method is clearly the best for culture of the specimen; if the physician has facilities for office

throat cultures for β-hemolytic streptococci, all that is necessary is the purchase of a quantitative loop for streaking the urine. This method is the one used by most clinical bacteriology laboratories and has an established record of practical utility in many physicians’ offices.19 It is probably the best method and can be combined with urine collection in Dixie cups, as described in the section on screening near the end of this chapter. Usually a 0.001 mL loop is used. The number of colonies of the same type are counted and then multiplied by 1000 to calculate the number of organisms per mL of urine.

throat cultures for β-hemolytic streptococci, all that is necessary is the purchase of a quantitative loop for streaking the urine. This method is the one used by most clinical bacteriology laboratories and has an established record of practical utility in many physicians’ offices.19 It is probably the best method and can be combined with urine collection in Dixie cups, as described in the section on screening near the end of this chapter. Usually a 0.001 mL loop is used. The number of colonies of the same type are counted and then multiplied by 1000 to calculate the number of organisms per mL of urine.

Susceptibility testing of isolates should not be attempted in the office, because too much standardization and several controls are required.

Other Bacteriologic Culture Methods

Dip slides have an agar coating and are simply dipped in the urine and then incubated. The inoculum of urine is less accurately measured than with the quantitative loop. However, the screw-cap tubes with an agar slide attached to the cap are convenient for transport, especially from home to office, and are sufficiently accurate for screening or follow-up.19,48,49

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree