Middle Respiratory Syndromes

General Concepts

The middle respiratory tract can be defined as the area from the top of the larynx to the bronchioles. Pharyngitis and other upper respiratory infections are discussed in Chapter 2. Pneumonia syndromes are discussed in Chapter 8, although the frequency and some of the physiologic problems of both pneumonia and middle respiratory syndromes are discussed in this section.

Respiratory physiology, respiratory insufficiency, and arterial blood gas analysis are discussed in simplified terms. More specialized textbooks should be consulted for further details.1,2,3

Symptoms in Pulmonary Disease

Tachypnea

Rapid breathing is often obvious, but counting and observing respirations is generally neglected. The child should be observed and examined without clothing covering the chest. If there is no cough or other physical sign of pulmonary disease accompanying the tachypnea, a metabolic acidosis (such as diabetic acidosis or acidosis from dehydration) should be suspected. In this case, the hyperventilation is a respiratory compensation for metabolic acidosis. If cough and other pulmonary signs are present, hypoxemia is the likely cause of the tachypnea. Fever in young children will often cause both tachypnea and tachycardia.

Acute Chest Pain

In children with respiratory disease, acute chest pain is usually increased by breathing (pleuritic) and indicates pleural disease, usually infection. Pain on coughing also implies pleuritic disease. In young children, pleural disease is manifested by splinting or unequal expansion.

Chest pain may be caused by pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum, which may be spontaneous or occur after mild trauma or coughing. Chest pain may also be related to anxiety, costochondritis, or strained intercostal muscles. Pulmonary embolism or infarction is exceedingly rare in children and should suggest a thrombotic disorder. Coxsackie B virus infection can cause fever and chest pain (pleurodynia).

Physical Signs in Pulmonary Disease

Anxiety

Facial expression and hyperactivity may imply anxiety, which in turn implies hypoxemia. Nasal flaring, retractions, and grunting also may be observed by simple inspection of the patient.

Splinting

Pain on inspiration can sometimes be inferred by observing protection of the involved side by holding it, not moving it as well, or by lying on it.

Names for Chest Signs

Rales are a fine crackling noise that may be simulated by rubbing the hair behind your ear between thumb and forefinger. They are also referred to as crackles and are more commonly inspiratory. They may be heard in pneumonia, bronchiolitis, atelectasis, and heart failure. End-inspiratory rales are typical of pneumonia. Rales that disappear after coughing are usually of no significance. Rhonchi are harsh upper airway noises that typically occur during both inspiration and expiration. Wheezes are high-pitched, whistling noises that occur most commonly during expiration and are produced by airflow through a partially obstructed airway. Polyphonic (musical) wheezes are typical of asthma, whereas those in other conditions (such as bronchomalacia) are often monophonic. Stridor is a high-pitched crowing sound that usually indicates large airway obstruction. If the obstruction is extrathoracic (from nose to midtrachea), the stridor is

mostly inspiratory, as in croup; if the obstruction is intrathoracic, the stridor is usually expiratory. Stertor is the name given to loud noises that occur because of nasopharyngeal restriction, usually from mucus (similar to snoring). Dyspnea, or distress during breathing, is manifested in children by nasal flaring, suprasternal and infrasternal retractions, cyanosis, and a rapid respiratory rate.

mostly inspiratory, as in croup; if the obstruction is intrathoracic, the stridor is usually expiratory. Stertor is the name given to loud noises that occur because of nasopharyngeal restriction, usually from mucus (similar to snoring). Dyspnea, or distress during breathing, is manifested in children by nasal flaring, suprasternal and infrasternal retractions, cyanosis, and a rapid respiratory rate.

Apnea Spells

Periods of not breathing (apnea) can have many causes. Apnea of less than 15 seconds is often a normal finding in infants, whereas apneic episodes longer than 15 seconds are usually abnormal. Certain infections can produce apnea,4,5 especially pertussis, chlamydia, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection (Box 7-1). Lower respiratory tract infection was the fourth most common discharge diagnosis in a study of 130 infants admitted with a diagnosis of apparent life-threatening event (ALTE).6 Among children with RSV infection, risk factors for apnea include young age, prematurity, hypercapnia, hypothermia, and atelectasis on chext x-ray.

Noninfectious causes in infants include seizures and gastroesophageal reflux.7

Classification

In middle and lower respiratory infections, a complete diagnosis ideally includes an anatomic diagnosis (such as “right middle lobe pneumonia”), an etiologic diagnosis (such as “probably pneumococcal”), and a physiologic diagnosis formulated as quantitatively as possible (such as “respiratory acidosis, probably well compensated now”). Thus, respiratory syndromes can be classified on the basis of anatomic syndrome, etiologic agent, or physiologic problem.

Anatomic Syndrome

It is customary to use the diagnostic term that indicates the most severe illness if more than one anatomic area is involved. For example, if the patient has both bronchitis and pneumonia, usually only pneumonia is recorded. Furthermore, a multiple term such as laryngotracheobronchitis (LTB) has the disadvantage of vagueness and diffuseness. The diagnosis of “croup syndrome” or “laryngitis” more accurately identifies the site of the most dangerous involvement: the larynx. The anatomic diagnosis should localize the disease as specifically as possible. For example, “bilateral interstitial pneumonia” is much more meaningful than simply “pneumonia.” In the following sections, the anatomic diagnoses are discussed, beginning with the larynx at the top of the tracheobronchial tree and descending to the small bronchioles (Box 7-2). Syndromes involving the alveoli and pleural space are discussed in Chapter 8.

Etiologic Classification

In the following sections, the etiologic diagnoses are discussed in terms of probabilities for each anatomic syndrome. A clinical prediction of the etiology of a patient’s lower respiratory infection can be made on the basis of the anatomic area involved, the particular clinical manifestations of the illness,

past statistical studies of similar cases, and Gram staining of specimens to be cultured.

past statistical studies of similar cases, and Gram staining of specimens to be cultured.

The general principles for the use of laboratory procedures and cultures for both pneumonia and middle respiratory infections are discussed at the beginning of Chapter 8. Etiologic diagnoses are important and necessary for specific chemotherapy. However, in severe lower respiratory infections, the early diagnosis and treatment of physiologic disturbances may be lifesaving.

Physiologic Disturbances

The physician should identify and evaluate the degree of physiologic disturbances in all patients with significant respiratory problems (Table 7-1).

Frequency

In a study of consecutive visits by 1,570 ill children to a pediatric group’s office in Rochester, New York, approximately one-fourth of all illnesses were respiratory infections.10 In a study of visits to an emergency room during hours that physicians’ offices were closed, children less than 18 years of age accounted for about 60% of the visits.11 Of the 858 randomly selected visits for infections, about 24% were classified as upper respiratory, 12% as middle respiratory, 6% as lower respiratory, 23% as pararespiratory (such as otitis or sinusitis), and 35% other infections. Thus, middle respiratory (airway) syndromes were twice as common as lower respiratory syndromes (pneumonia).

TABLE 7-1. MIDDLE AND LOWER RESPIRATORY PHYSIOLOGIC PROBLEMS | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Respiratory Insufficiency

Respiratory insufficiency can lead to acute respiratory failure, defined as hypoxemia, hypercarbia (respiratory acidosis) or both.12 The clinician must be able to recognize the clinical signs that suggest impending respiratory failure.13,14

Respiratory Acidosis

Resulting from excess CO2 (hypercarbia), respiratory acidosis is secondary to hypoventilation or a severe ventilation–perfusion mismatch. Signs of acute respiratory acidosis include sweating, anxious expression on the face, falling rates of respiration and pulse, and rising blood pressure. Cyanosis is a late sign. A widened QRS pattern on EKG also occurs later. Because acute CO2 retention is typically the result of hypoventilation, it is usually best treated by mechanical ventilation unless the cause of the hypoventilation can be rapidly reversed.

Hypoxemia

This is defined as a low arterial pO2, whereas hypoxia implies oxygen deficiency in the tissues. Hypoxemia is usually secondary to ventilation–perfusion imbalance, venous-to-arterial shunt, hypoventilation,

or diffusion impairment. Signs of hypoxemia include tachypnea, cyanosis, restlessness, poor judgment, weakness, and confusion. In severe hypoxia, the muscle tone is poor, and the patient is often limp. Hypoxemia is best treated with oxygen, first with increased concentrations, then assisted ventilation if necessary. Spot or continuous monitoring of oxygen saturation provides a useful guide for the administration of oxygen.

or diffusion impairment. Signs of hypoxemia include tachypnea, cyanosis, restlessness, poor judgment, weakness, and confusion. In severe hypoxia, the muscle tone is poor, and the patient is often limp. Hypoxemia is best treated with oxygen, first with increased concentrations, then assisted ventilation if necessary. Spot or continuous monitoring of oxygen saturation provides a useful guide for the administration of oxygen.

Anticipation of Respiratory Insufficiency

The most serious error in the treatment of middle or lower respiratory infections is to fail to recognize how seriously ill the patient really is. Early recognition of respiratory insufficiency is difficult unless the physician is experienced and can make frequent clinical observations. Therefore, if there is doubt, the patient should be transferred to a location where intensive observation can be done and arterial blood gases measured frequently and accurately.

Cough Only

Cough only is a useful preliminary diagnosis when cough is present without fever, rhonchi, rales, or dyspnea. By definition, it is an isolated symptom, without lower respiratory signs and without fever (rectal temperature 101°F = 38.4°C). Chronic cough can be defined as persistence of a cough for more than 3 weeks.15 Except for psychological coughs,16 this symptom usually reflects irritation of the tracheobronchial tree. This irritation may be caused by inhalants (such as cigarette smoke), local inflammation, or secretions entering the trachea from above (sinuses). Cough only is rarely caused by pulmonary parenchymal disease, as discussed later.

Causes and Diagnostic Approach

The possible causes of cough only are listed in Box 7-3. Asthma is a common cause of chronic cough in children.17,18 Although there is much controversy about the diagnosis of cough-variant asthma, most experts agree that some children do display their asthma with cough alone. These children have abnormal pulmonary function tests and an abnormal response to methacholine challenge similar to those with classic asthma. Children with cough-variant ashthma often have a family or personal history of atopy. Cough is likely to be worse at night, to disrupt sleep, and to sound like the cough of a classic asthmatic.19 Cough may also be exacerbated by exercise or exposure to cold air. Some of these patients will go on to develop classic wheezing asthma over time. Chronic cough is by no means synonymous with cough-variant asthma, however, and failure to respond to bronchodilator or anti-inflammatory therapy over the course of several weeks should lead the physician to consider other diagnostic possibilities.

BOX 7-3 Possible Causes of Cough Only

| Cough-variant asthma Postinfectious (after bronchitis, influenza, pertussis, mycoplasmal infection) Foreign body in larynx or bronchus Rhinitis, sinusitis, or postnasal drip syndrome Habit cough Smoking (active or passive) Irritation of the pleura, diaphragm, or pericardium Irritation of the auricular branch of the vagus nerve (foreign body or wax in ear canal) Elongated uvula Tourette’s syndrome Gastroesophageal reflux Vascular ring or vascular sling Pollution or irritant exposure (environmental dust, cigarette smoke, etc.) |

Cystic fibrosis is a rare cause of cough only. Sweat chloride concentration should be measured in children who have nasal polyps, poor growth, or both in addition to cough. Radiologic evidence of pulmonary disease is usually present in patients with cough secondary to cystic fibrosis.

The quality of the cough may also be instructive. Seal-like or croupy cough suggests tracheomalacia. The cough of children with vascular rings may have a similar quality.

Subacute or chronic sinusitis may cause cough in the absence of either headache or fever, as discussed in Chapter 5. History may reveal that the cough began during an episode of the common cold syndrome. Thus it must be differentiated from postviral cough syndrome, which occurs in the absence of demonstrable sinus infection. Sinus serie x-rays or coronal computed tomography (CT) may be helpful when the diagnosis is seriously considered.20

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) may cause a wet-sounding cough that occurs mostly when the infant

or child is lying down. Paradoxically, it has been shown that thickening the formula with rice cereal actually increases the frequency of cough in infants with GER.21

or child is lying down. Paradoxically, it has been shown that thickening the formula with rice cereal actually increases the frequency of cough in infants with GER.21

Children may aspirate a foreign body, such as a peanut, which may lodge in any part of the airway. Typically, the child is 1 to 2 years old.22 There may be a history of a foreign body in the mouth, usually a food, with an episode of falling or choking, followed by persistent cough, unilateral wheezing, and decreased air entry on the affected side.23 Unfortunately, the actual aspiration event is often unwitnessed and may be followed by a clinically silent stage. The aspirated foreign body is often vegetable matter and is therefore radiolucent. This may rarely lead to a child presenting with a chronic intractable pneumonia.24 Laryngoscopy or bronchoscopy is often necessary. If a foreign body is suspected, rigid rather than flexible bronchoscopy is preferred.25

A careful history and physical examination can establish the cause of cough in most cases. Chest x-ray is usually indicated. Children older than 6 years should undergo pulmonary function testing. Exercise challenge or methacholine challenge are usually not necessary. A history of possible exposures to tuberculosis should be taken and, if positive, tuberculin skin testing performed. In one series of children with chronic cough, a trial of therapy directed at the most likely cause established the diagnosis in 58% of cases.26

Barium swallow or endoscopy should be considered if the preceding studies are negative and the cough persists, especially in infants.27

TABLE 7-2. FINDINGS IN LARYNGEAL SYNDROMES | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Treatment

No specific therapy is needed in the absence of a specific etiology. Symptomatic therapy includes attempts to improve humidification and use of over-the-counter antihistamines to decrease postnasal drip.

Cough syrups are discussed in Chapter 2. They should be avoided in young children, as no cough suppressant has been studied for efficacy or safety in children less than 2 years of age.

Laryngeal Syndromes

Definitions

The manifestations of laryngitis may include stridor and voice changes such as hoarseness, a barking or brassy cough, or aphonia (usually due to refusal to speak). The child may indicate to the parent that the “throat” (laryngeal area) is sore.

In adults, laryngitis is recognized by hoarseness. In children, subglottic laryngitis is usually called croup. Inspiratory stridor is the most characteristic sign in laryngitis and is the hallmark of high respiratory obstruction of any cause (Table 7-2). Substernal inspiratory retraction is typically present in moderate to severe cases and also is a general sign of upper airway (extrathoracic) obstruction.

A child with laryngitis or any other upper airway obstruction has trouble getting air into the lungs, whereas the child with bronchiolitis, or other lower airway (intrathoracic) obstruction, has trouble getting air out of the lungs. In laryngitis, breath sounds are usually decreased throughout all lung fields, and this is usually described as poor air entry or exchange.

Classification

The literature contains a dizzying array of different diagnostic terms for the various conditions that affect the larynx and trachea. Laryngitis is a working diagnosis that is best used when the location of the laryngeal disease cannot be further identified. Laryngitis can be classified into subglottic or supraglottic laryngitis. Although it is useful to distinguish between supraglottic and subglottic laryngitis, this distinction is often difficult when the child is first seen. Laryngitis or croup syndrome is a useful preliminary descriptive diagnosis until more definitive information (such as a lateral roentgenogram of the neck) is available. “Croup syndrome” also has been used to emphasize the variety of possible causes and location of the laryngeal disease. In this section, “croup” is used to refer to subglottic laryngitis, presumably viral (Table 7-2). “Epiglottitis” is an imprecise term often used in place of the better “supraglottitis;” the latter term is superior because the epiglottis may be minimally involved in some cases in which most of the swelling is in the aryepiglottic folds. Spasmodic croup is also a poor name, due to the lack of evidence that laryngospasm plays an etiologic role in the condition. Preferred terms are as follows (with the usual terms in parentheses): croup, supraglottitis (epiglottitis), episodic croup (spasmodic croup), and suppurative tracheitis, laryngotracheitis, laryngotracheobronchitis, or lary-ngotracheobronchopneumonitis (bacterial tracheitis), depending on the extent of the bacterial superinfection.

Severe laryngitis, whether subglottic or supraglottic, is an extremely important pediatric emergency. It may be necessary to call an anesthesiologist or otorhinolaryngologist to perform tracheal intubation or tracheostomy. The primary care physician in training should learn to perform difficult intubations as well as emergency ventilation with a bag and mask. However, intubation may be impossible in some patients with supraglottitis (epiglottitis), so an operative airway procedure, such as tracheostomy or cricothyroid membrane puncture, may be needed.

Age and Frequency

Laryngitis in adults characteristically produces only hoarseness or loss of voice. However, when children have laryngitis, they may have a much more serious illness because the larynx is smaller. Edema in a child’s larynx thus produces more obstruction of the airway than the same amount of edema in an adult. Another important factor is that young children are usually experiencing primary infection with a particular respiratory virus, whereas adults will have been previously infected. Primary infection with the parainfluenza viruses and respiratory syncytial virus tends to be more severe and to spread more widely in the respiratory tract. This is in contrast to second or later infections, in which these viruses tend to be restricted to the upper airway.

Hospitalization is needed for only a small percentage of patients with laryngitis seen in an office or outpatient clinic. Although only a few children hospitalized because of croup are likely to need intubation, the possibility of acute progression of the obstruction must always be remembered.

Viral croup tends to be seasonal, especially when caused by parainfluenza virus type 1, its most frequent etiologic agent. Peak time for admissions from croup in temperate climates is late fall, and the epidemic is more severe in odd-numbered years.28 Parainfluenza type 3 can also produce severe croup in an endemic pattern. Summertime croup may be due to enteroviruses, adenovirus, or parainfluenza type 3.

Supraglottitis, in contrast, has no seasonal peak. This disease, almost always caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b bacteremia, has been virtually eradicated. The peak age frequency for croup is 1–3 years. Supraglottitis occurs in older children, with a peak between 3 and 6 years. Suppurative tracheobronchitis also tends to be a disease of preschool and school-age children.

Physiologic Principles

Laryngeal Edema

The major components in laryngeal obstruction in laryngitis are edema and spasm.

Laryngospasm

Laryngospasm is a feared complication of supraglottitis. Manipulation of the posterior pharynx, such as gagging the patient with a tongue blade, may produce aspiration of secretions, laryngospasm, or both and lead to rapid obstruction of the airway. Examination of the posterior pharynx should not be attempted in the child with severe respiratory distress suspected to be caused by supraglottitis, especially if it involves restraining the child in the supine position. In an older child who can cooperate and in whom supraglottitis is thought to be unlikely, a skilled laryngoscopist can sometimes perform indirect laryngoscopy to exclude the diagnosis.29 However, equipment and skills should be available for bag and mask ventilation and intubation if direct visual examination is attempted.

The principal cause of episodic croup (“spasmodic croup”) is not, as the name suggests, laryngospasm, but rather acute edematous swelling of the subglottic tissues. What causes this process is not well understood. The appearance of the tissues is that of noninflammatory edema.

Purulent Secretions

Rarely, purulent secretions add to obstruction in the trachea and major bronchi. Suctioning is unnecessary in most forms of laryngitis and should usually be avoided, because trauma from the suctioning tube may make the spasm or edema worse.

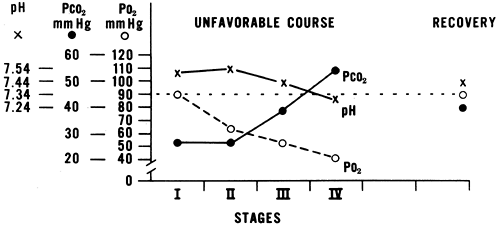

Hypoxemia

The principal physiologic disturbance in croup is hypoxemia,30 the mechanism of which is complex. It may be caused by a diffusion block from involvement of the lower airways with infection or by pulmonary edema secondary to high resistance. In any case, low arterial pO2 is frequently present in croup.30 CO2 retention is unusual, and the pCO2 is usually low because of hyperventilation. When the pCO2 becomes normal or elevated, the ventilation may be inadequate, indicating a more serious situation (see Fig. 7-1). Except for a rising pCO2, blood gases are not well correlated with the need for intubation.31

Clinical Appearance of Laryngeal Syndromes

Acute upper respiratory obstruction can be classified into several anatomic syndromes on the basis of the location of the obstruction and the clinical findings (Table 7-2). However, the syndromes often cannot be distinguished early in the course. Mild viral croup and episodic croup often may not be distinguishable.

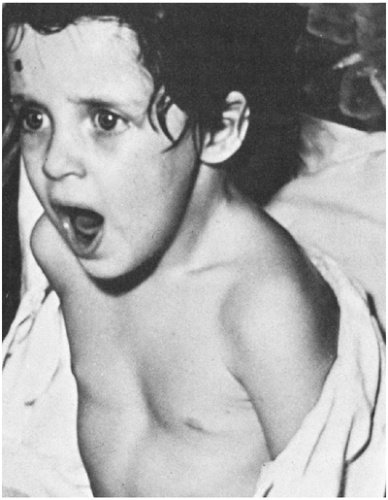

Supraglottitis (Epiglottitis)

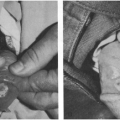

Obstruction by edema at and above the glottis (vocal cords) is characterized by pooling of secretions in the pharynx, with drooling. The position of comfort is sitting with the chin forward (Fig. 7-2).32 Respirations may be slow and careful. Swelling of the entire neck is sometimes observed. The voice is absent (aphonia) or is hoarse, muffled, or guttural. The patient generally appears quite anxious. Onset of the disease is usually quite rapid, and, because this condition is usually accompanied by

bacteremia, high fever is seen. This syndrome is an urgent situation, because obstruction may occur suddenly. The epiglottis may be cherry red and spherical, but rarely it can be normal, with the edema localized to the aryepiglottic folds.

bacteremia, high fever is seen. This syndrome is an urgent situation, because obstruction may occur suddenly. The epiglottis may be cherry red and spherical, but rarely it can be normal, with the edema localized to the aryepiglottic folds.

Croup

Obstruction by edema below the vocal cords is characterized by pooling of secretions below the vocal cords in the trachea or by edema in the conus elasticus, the loose alveolar tissue below the vocal cords. The position of comfort is usually a lying position, but the child may prefer lying on the back with the neck hyperextended over a pillow. Respiration is usually rapid. There is a brassy or barking cough, usually without hoarseness. Aphonia is uncommon. This form of laryngitis usually has a gradual onset and course, with fatigue as a major factor in respiratory insufficiency. There is sometimes a history of croup.

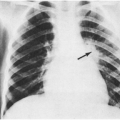

Purulent Tracheobronchitis

Also called bacterial tracheitis and pseudomembranous tracheitis, purulent tracheobronchitis should be considered as a separate entity, because the physiologic disturbance and treatment are different from those of the preceding two syndromes.33,34,35,36,37 The condition resembles croup with minimal laryngeal manifestations. Often, a foreign body is suspected because of focal low-pitched inspiratory and expiratory wheezes.35 It is characterized by pooling of purulent secretions in the trachea and major bronchi. Copious amounts of purulent secretions may be coughed up or suctioned. Laryngeal manifestations are minimal or variable, so that the severity of obstruction may not be recognized. Brassy cough and croupy stridor are usually not present, although viral tracheitis may be a predisposing factor.36 However, coarse inspiratory and expiratory wheezes, and sometimes rales, can be heard with a stethoscope. Air trapping is common. The wheezing may be lateralized to one major bronchus, which is partially obstructed by purulent secretions, and this may raise the suspicion of a foreign body. Atelectasis is common in severe cases. Chest x-ray may reveal diffuse pulmonary involvement, and sometimes loose pseudomembranes can be seen. Lateral films more easily reveal the narrowing of the tracheal airway with shaggy borders due to thick, purulent secretions.

Acute respiratory insufficiency may occur because of acute obstruction at the trachea or several major bronchi. Nasotracheal intubation or bronchoscopy and suctioning may be lifesaving. A tracheostomy may be necessary to facilitate suctioning. It is important to diagnose this condition rapidly, as a delay in diagnosis leads to poorer outcome.

Episodic Croup (Spasmodic Croup)

This clinical pattern is characterized by sudden onset of croupy cough and inspiratory stridor that typically lasts less than a day or begins to improve in less than a day.38 Recurrences are common. The syndrome usually develops in a child who was well or only minimally sick at the time he was placed to bed. The patient then awakens with a brassy cough, with or without inspiratory stridor. Fever is absent.

Laryngoscopic examination reveals that the symptoms are caused by the rapid accumulation of edema in the laryngeal tissues. Viral infections are usually implicated, but why some children develop this sudden edema is not well understood. This predisposition tends to run in families. Long-term follow-up studies reveal a higher incidence of asthma in patients with a history of episodic croup.

Rapid response to mist is usually seen. Sometimes, the drive to the hospital will be enough to completely eliminate the symptoms. It tends to recur, sometimes in the same night, and almost always on subsequent nights for 1 to 4 days. During the day the child will occur well or nearly so. Parents can expose the child to mist from the bathroom shower, or may be able to hold off a recurrence by adequately humidifying the child’s bedroom. Mist need not be cool. Despite its initial sometimes frightening appearance, episodic croup is almost always benign.

Possible Etiologies

Viruses

Parainfluenza viruses are the most common viral cause of croup and appear to account for 30–40% of the laryngitis in children.39 Extrapolations from epidemiologic studies suggest that parainfluenza viruses account for approximately 250,000 emergency room visits, 70,000 hospitalizations, and about $190 million in health care costs each year in the United States alone.40 Parainfluenza viruses types 1 and 3 cause moderate to severe croup, whereas the course of croup secondary to parainfluenza virus type 2 is generally mild. RSV, influenza A and B, adenoviruses, and enteroviruses are occasional causes of croup syndrome, as is the newly discovered human metapupumovirus.39 Croup caused by a virus usually has a gradual onset and gradual course, although croup secondary to influenza virus can be unusually severe.41

There is a fairly high rate of croup syndrome in children with measles infection. Several outbreaks of measles were reported among undervaccinated populations in the early 1990s; in one of these, 82 (19%) of 440 children diagnosed as having measles also had croup.42

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) has been identified as the cause of prolonged croup symptoms in patients with severe gingivostomatitis.43 Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) was the cause in one 12-year-old who developed a pseudomembrane.44

Parainfluenza or influenza viruses appear to be rare causes of supraglottic laryngitis.45

A particularly recalcitrant cause of recurrent hoarseness, stridor, and sometimes respiratory obstruction is laryngeal papillomatosis, a condition caused by human papillomaviruses (usually serotype 6 or 11) that are acquired via passage through the birth canal. Multiple and sometimes frequent surgical procedures may be required to relieve obstructive symptoms.

Bacteria

H. influenzae supraglottitis may be an extreme medical emergency. It usually is characterized by the findings of supraglottic obstruction, with a red swollen epiglottis and a rapid course.46,47 In a few cases of H. influenzae laryngitis, the subglottic area may be the major focus of the obstruction.

Other bacteria, particularly Groups A, B, or C beta-hemolytic streptococci, may rarely produce severe laryngitis.48,49,50 Mycoplasma pneumoniae has been associated with croup in some patients. Diphtheria may produce a membranous obstruction in the larynx or trachea. This disease is now relatively rare but should still be considered, especially when exudative pharyngitis is present with croup in an unimmunized child. Staphylococcus aureus is the usual cause of purulent tracheobronchitis according to cultures of the purulent tracheal aspirates. Gram-negative enteric organisms are rarely implicated in purulent laryngotracheobronchitis.

Previous immunization with H. influenzae type b vaccine does not exclude the possibility of H. influenzae supraglottitis, but a child who has received the entire immunization series is highly unlikely to develop this disease. In addition, herd immunity from the widespread use of the vaccine has rendered the condition rare, even in unimmunized children.

Fungi

Foreign Body

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) can be a cause of episodic croup. One retrospective study of 66

patients with recurrent croup episodes found that 47% of the patients had GER.55 Because of its retrospective nature this study was likely subject to selection bias. However, the authors did demonstrate a “dose-response” relationship of sorts; children who were hospitalized three or more times for croup had a higher prevalence of GER.55 These patients tended to be younger and to have a shorter interval between episodes of croup. No controls were evaluated. Another small study documented that eight of eight children with recurrent croup who underwent esophageal pH probe studies had GER. Six control subjects had normal pH probe studies.56

patients with recurrent croup episodes found that 47% of the patients had GER.55 Because of its retrospective nature this study was likely subject to selection bias. However, the authors did demonstrate a “dose-response” relationship of sorts; children who were hospitalized three or more times for croup had a higher prevalence of GER.55 These patients tended to be younger and to have a shorter interval between episodes of croup. No controls were evaluated. Another small study documented that eight of eight children with recurrent croup who underwent esophageal pH probe studies had GER. Six control subjects had normal pH probe studies.56

Allergy or Irritation

Allergic laryngeal edema can be severe and dangerous. Inhaled irritants can produce laryngeal spasm in individuals who are particularly susceptible. This may be one possible cause of episodic croup. Some cases appear to be precipitated by cold air (e.g., from an air conditioner). Aspiration of a small amount of gastric contents also appears to be an occasional cause of laryngeal irritation and a crouplike illness. Toxic inhalants can produce an episodic croup.57 Hot beverages can cause thermal epiglottitis in infants.

Other Syndromes

Laryngitis may be suspected when upper airway obstruction results in inspiratory stridor. Retropharyngeal abscess can produce stridor and is discussed further in Chapter 6. Epilepsy can cause recurrent laryngospasm.58 Hereditary angioedema can produce the rapid onset of symptoms of croup. This condition is related to C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency.58a Teenagers may present with acute upper airway obstruction due to vocal cord dysfunction. This condition is caused by paradoxical closure of the vocal cords and may present with stridor or wheezing. It is most common in adolescent females and responds to speech therapy and psychotherapy.59

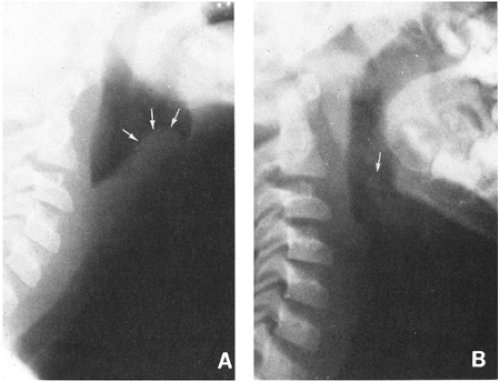

FIGURE 7-3 Roentgenogram of lateral neck in epiglottis. (A) Epiglottitis; (B) normal. Compare with Figure 7-4. (Rapkin RH: J Pediatr 1972;80:96–98) |

Diagnostic Approach

Lateral Neck Radiograph

These radiographs, ordered for viewing the soft tissues rather than the cervical spine, are frequently used to determine the area of obstruction when the patient’s condition is good (Figs. 7-3 and 7-4). Radiographs of the lateral neck require experience to interpret, and comparison with diagrams of this area may be helpful (Figs. 7-3 and 7-4). Anteroposterior views may show subglottic edema in supraglottic laryngitis, in addition to supraglottic edema.60 A radiopaque foreign body can be excluded by these radiographs. A review of lateral neck radiographs by radiologists who did not know the diagnosis indicated that for subglottic laryngitis, the interpretation is very reliable except in severe cases with unreadable roentgenograms.61 A newer

study compared the results of plain radiography with diagnosis made at microlaryngoscopy and bronchoscopy in 144 children with acute upper airway obstruction.62 X-ray diagnosis was > 86% sensitive for diagnosing suppurative laryngotracheitis, foreign body, and innominate artery compression. The sensitivity of plain films in the diagnosis of laryngomalacia and tracheomalacia was 5% and 62%, respectively.62 Another review indicated that poor-quality radiographs interfered with accurate radiologic interpretation.63

study compared the results of plain radiography with diagnosis made at microlaryngoscopy and bronchoscopy in 144 children with acute upper airway obstruction.62 X-ray diagnosis was > 86% sensitive for diagnosing suppurative laryngotracheitis, foreign body, and innominate artery compression. The sensitivity of plain films in the diagnosis of laryngomalacia and tracheomalacia was 5% and 62%, respectively.62 Another review indicated that poor-quality radiographs interfered with accurate radiologic interpretation.63

FIGURE 7-4 Diagrams of lateral neck radiographs in laryngitis. (A) Normal anatomy; the esophagus is normally not visible on lateral neck roentgenograms because it does not contain air. (B) Roentgenogram in epiglottitis; as shown in Figure 7-3A. (C) Normal roentgenogram as shown in Figure 7-3B. (D) Roentgenogram in another case of epiglottitis. (E) Roentgenogram in subglottic laryngitis. (D and E from Poole CA, Altman D: Radiology 1963;80:798–805) |

A child in severe respiratory distress should not be sent for a radiograph but should have a direct examination with operating room facilities, an anesthesiologist, and an otolaryngologist who can intubate or do endoscopy or tracheostomy. Even a mildly ill child should be accompanied by someone capable of providing an emergency airway or ventilation.

White Blood Cell Count and Differential

Sometimes, a white cell count and differential is used as a guide to whether antibiotics should be used; these studies usually are of no special value. No laboratory values were of use in distinguishing viral croup from purulent tracheobronchitis in one small study.64

Cultures

Throat culture for bacteria is of no value. Tracheal secretions recovered at the time of intubation should be cultured for H. influenzae and other bacteria, as well as for viruses. Blood culture may be of value in children with suspected supraglottitis, although the yield is low. Patients with croup need not undergo blood culturing. In a study of 249 highly febrile (temperature > 39°C) children between the ages of 3 and 36 months who had a clinical diagnosis of croup,65 none had a positive culture.

Arterial Blood Gases

If the patient appears seriously ill and possibly in need of an airway soon, then restraint, such as for arterial puncture, should not be done. Capillary blood gases are most useful in a gradually progressive illness where the adequacy of air exchange may be difficult to assess but did not correlate with the need for endotracheal intubation in one study of croup and epiglottitis.31

Treatment of Suspected Supraglottitis

Although supraglottitis is rarely seen, its diagnosis and treatment are critical because it can be rapidly fatal. Therefore, a discussion of its treatment is first.

It is sometimes difficult for the clinician to distinguish between the two major kinds of laryngitis; a cautious approach is indicated. Hospitals should have their own written protocol for management of a child with suspected supraglottitis.47,66,67 The following approach is based on the possibility that the child might have supraglottitis (Box 7-4).

It is sometimes difficult for the clinician to distinguish between the two major kinds of laryngitis; a cautious approach is indicated. Hospitals should have their own written protocol for management of a child with suspected supraglottitis.47,66,67 The following approach is based on the possibility that the child might have supraglottitis (Box 7-4).

Tracheal Intubation

In severe laryngeal obstruction, tracheal intubation may be needed.68,69,70,71,72,73 It has been used successfully instead of tracheotomy in most cases of acute epi-glottitis, but the risk of delayed or unsuccessful intubation is always present, especially if laryngeal edema is severe.

BOX 7-4 Summary of Priorities in Severe Laryngitis

|

The principal value of this procedure is its immediate availability for emergency use. It appears to be preferable when experienced personnel are available for intubation. The major disadvantage is the occasional postintubation complication of subglottic stenosis, which is a greater problem than removal of the tube from a tracheostomy.

Antibiotics

Ceftriaxone (or its equivalent) is indicated for feb-rile, toxic patients. Antibiotics do not decrease the need for careful observation early in the course of severe laryngitis and have a lower priority than evaluation of the airway.

Treatment of Croup

The management of severe croup includes many of the same steps described previously for supraglottitis (Box 7-4). Other treatment possibilities for croup follow.

Nebulized Racemic Epinephrine

This is a mixture of equal parts of d and l (ordinary) epinephrine. Because d-epinephrine has relatively little activity, the equal parts mixture gets its activity almost entirely from the l-epinephrine (the form commonly available diluted 1:1000). Thus, the standard preparation of 2.25% racemic (d,l) epinephrine is physiologically equivalent to 1% epinephrine (USP). A small but well-designed study that assigned 16 children with severe croup to racemic epinephrine and 15 to l-epinephrine treatment demonstrated that l-epinephrine is at least as effective as racemic epinephrine.75 L-epinephrine has the advantages of lower cost, more widespread availability, and potentially lower adverse event rate.

Epinephrine apparently produces relief of obstruction by local vasoconstriction, which shrinks the edematous mucosa. Epinephrine is widely used

and appears to be helpful in laryngotracheitis, at least for several hours.76 The usual dose is 2.5% racemic epinephrine or 1% l-epinephrine diluted 1:8 (0.5 ml of epinephrine in 3.5 ml distilled water) given by face mask without positive pressure.77 One drawback of nebulized epinephrine has been the potential for rebound, wherein the patient transiently improves but then becomes quite suddenly worse when the therapy “wears off.” Because of this concern, it was once widely believed that patients who received epinephrine in the emergency department needed to be admitted to the hospital. A prospective cohort study showed that patients with croup who received both epinephrine and dexa-methasone and, at the end of a two-hour observation period, had neither stridor nor intercostal retractions at rest could be safely discharged home.78 Of 82 patients treated in this way, only 6 required more therapy within the next 48 hours and only 2 required hospital admission.78 Nebulized epinephrine is not without risk, however. A recent report tells of a young child who developed an acute myocardial infarction after receiving multiple doses of racemic epinephrine in the emergency department.79

and appears to be helpful in laryngotracheitis, at least for several hours.76 The usual dose is 2.5% racemic epinephrine or 1% l-epinephrine diluted 1:8 (0.5 ml of epinephrine in 3.5 ml distilled water) given by face mask without positive pressure.77 One drawback of nebulized epinephrine has been the potential for rebound, wherein the patient transiently improves but then becomes quite suddenly worse when the therapy “wears off.” Because of this concern, it was once widely believed that patients who received epinephrine in the emergency department needed to be admitted to the hospital. A prospective cohort study showed that patients with croup who received both epinephrine and dexa-methasone and, at the end of a two-hour observation period, had neither stridor nor intercostal retractions at rest could be safely discharged home.78 Of 82 patients treated in this way, only 6 required more therapy within the next 48 hours and only 2 required hospital admission.78 Nebulized epinephrine is not without risk, however. A recent report tells of a young child who developed an acute myocardial infarction after receiving multiple doses of racemic epinephrine in the emergency department.79

Corticosteroids

Although some small, early studies showed no benefit from the administration of corticosteroids, there is now a substantial body of literature supporting their use. Steroid therapy should be reserved for patients with moderate to severe croup and used sparingly, if at all, in patients who present with classic episodic croup, who usually respond quite rapidly to nebulized saline. Patients with severe episodic croup, however, do respond to corticosteroids; thus, this treatment can be selectively employed. If the patient requires a prolonged course of therapy or increasing doses to control symptoms, referral to an ear, nose, and throat specialist for laryngoscopy should be made. Many studies have been criticized for failing to sort out episodic croup, but this criticism is not correct. Supraglottitis and purulent tracheobronchitis are readily excluded clinically, whereas patients with mild episodic croup rarely are hospitalized. Patients with severe episodic croup requiring hospitalization often cannot be adequately distinguished from patients with viral croup, as defined in this section. Thus, studies with adequate numbers and adequate controls that indicate benefit should not be discarded because of failure to make clinical diagnostic determinations that are difficult or impossible. The variations in severity should fall equally into placebo and treated groups if randomization is done correctly.

Studies show that corticosteroids are effective in croup whether they are administered intramuscularly, by nebulization, or by the oral route. A prospective, randomized, blinded study of 144 children with moderate to severe croup compared intramuscular dexamethasone or inhaled budesonide to placebo.80 All patients were also given nebulized epinephrine. Hospitalization rates were 71% in the placebo group, 38% in the nebulized budesonide group, and 23% in the intramuscular dexamethasone group.80 Oral dexamethasone at a dose of 0.15 mg/kg administered to patients with mild croup produced a measurable benefit: none of 50 patients who received the steroid treatment versus 8 (16%) of 50 who received placebo returned for further medical care during the same illness.81 This study, however, failed to demonstrate a difference in the total duration of croup symptoms or the duration of symptoms of viral illness. This result is in agreement with the conclusions of a meta-analysis of 24 studies of corticosteroids in the management of croup, which demonstrated improved croup scores at 6 and 12 hours after steroid administration, but not at 24 hours.82 The benefits of glucocorticoid treatment in laryngotracheitis, then, are transient but real; short-term improvement is often all that is needed to alleviate troublesome symptoms and avert hospitalization in this patient group.

Currently, 0.3 to 0.5 mg/kg of dexamethasone intramuscularly can be recommended in severe croup, especially when there will be a delay of 30 minutes or longer before receiving oxygen and mist in the hospital.

Epinephrine

Use of a trial of 0.01 ml/kg of the standard aqueous solution of 1:1000 epinephrine intramuscularly is reasonable when an allergic basis is strongly suspected, whether of episodic croup or supraglottic allergic edema.

Helium–Oxygen Mixtures

Because its density is less than nitrogen, helium, when mixed with oxygen, should facilitate oxygen passage through partially obstructed airways. However, its use is still investigational, and in one study in newborns with subglottic stenosis, the mixture resulted in hypoxemia.83

Complications

Pulmonary Edema

Extralaryngeal Infection

Meningitis, pericarditis, and septic arthritis are extremely rare complications of H. influenzae epiglottitis.46

Bronchitis and Coughing Syndromes

Definitions

There exists no clear consensus on an operational definition of acute bronchitis in childhood. The dictionary definition, “inflammation of the bronchi,” is clearly inconvenient for diagnostic purposes, as the bronchi cannot be visualized noninvasively. For many busy practitioners, the term bronchitis has been a “trash can” diagnosis, into which all children who are “too sick to have a common cold, but too well to have pneumonia” have been tossed. Physicians may also make the diagnosis of bronchitis to justify the administration of antimicrobial agents when they are expected by a child’s parents,86 although the diagnosis generally fails to provide an indication for antibiotic therapy. Acute bronchitis is probably best defined as cough with rhonchi or coarse crackles that clear with coughing and no evidence of pneumonia. The cough may be paroxysmal or nighttime. Tracheitis is often present. Fever is generally present but usually not significant. If marked lymphocytosis or a whoop is present, it is a pertussis-like illness (Table 7-3). If headache and weakness are prominent, the condition should be diagnosed as an influenza-like illness. If wheezing is present and persistent, the illness is usually diagnosed as asthmatic bronchitis (Table 7-4).

Bronchiolitis and asthmatic bronchitis are discussed in a later section on wheezing syndromes.

Classification

Acute bronchitis in children can be classified into subgroups and possible etiologies according to additional features (see Table 7-3). The table distinguishing bronchiolitis, asthmatic bronchitis, and asthma (Table 7-4) should be used to complete the spectrum of syndromes.

TABLE 7-3. CLASSIFICATION OF ACUTE COUGHING SYNDROMES | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Epidemiology and Pathology

The diagnosis of “bronchitis” is very common in pediatric practice. In one study of 5,489 outpatients with respiratory tract illnesses other than common cold, 40% were assigned the diagnosis of acute bronchitis.87

Clearly established predisposing factors include day-care attendance and passive smoking. Former premature babies with bronchopulmonary dysplasia often present with recurrent bronchitis. Some reports suggest that children with IgG subclass deficiencies are at higher risk for bronchitis, especially in recurrent or chronic form.88,89 Measurement of IgG subclasses is not likely to be informative in children younger than 3 years.

TABLE 7-4. DIFFERENTIATION OF THREE WHEEZING SYNDROMES | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Because bronchitis is rarely fatal, little is known about the histopathology of this condition. One report examined the results of bronchial biopsy and bronchial wash specimens in nonatopic children with a history of chronic bronchitis.90 Despite the fact that the specimens were collected at a time when the children had not had a recent acute infection, 87% of the specimens showed extensive respiratory epithelial damage. Lymphocytic infiltration, edema, increased protein content of mucus, and decreased mucociliary function were all demonstrated.90

Causes

Respiratory Viruses

The grand majority of cases are due to infection with a respiratory virus. Adenoviruses (especially types 4 and 7), influenza, parainfluenza, and RSV are the most common causes of acute bronchitis in childhood. Rhinovirus and some enteroviruses are also capable of causing acute bronchitis.87 Adenoviruses have been reported to produce an illness indistinguishable from classical whooping cough, including the marked lymphocytosis91. However, subsequent reports concluded that the adenovirus may have been reactivated by Bordetella pertussis (which is very difficult to culture), and statistical evidence does not support a role for adenoviruses in pertussis-like illnesses.92 Of the parainfluenza viruses, type 3 is a more common cause of bronchitis than either type 1 or type 2, in contradistinction to the relative frequencies seen in croup.

Measles virus infection always involves the bronchi. As discussed in Chapter 11 on rashes, coughing and fever are prominent before the eruption of the rash.

Mycoplasmas

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is an occasional cause of acute bronchitis, especially in school-age children.91 Radiologic or clinical evidence of pneumonia is not detected, despite prominent cough and fever. Poor air exchange and even cyanosis may be present. Cold agglutinins are often positive in this disease, although the presence of IgM antibodies to M. pneumoniae is a more sensitive and specific test.

Chlamydia

C. trachomatis can cause cough and tachypnea in the infant 1 to 6 months of age along with a bilateral interstitial pneumonia and sometimes an eosinophilia.93 It is discussed further in the section on pulmonary infiltrates with eosinophilia in Chapter 8.

There is conflicting information on the role of C. pneumoniae in acute bronchitis, largely because the diagnosis of C. pneumoniae infection is fraught with difficulty. Because it grows in cell culture only, it cannot be cultivated on typical agar plates used for isolating bacteria. It needs to be transported in proper media and kept cold. Direct antigen testing is fairly unreliable. Of late, reports on the use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the detection of C. pneumoniae have been appearing, but further evaluation will be required. Serologic responses can be suggestive of recent infection; an IgM response appears in about 3 weeks and IgG at about 6 to

8 weeks. Grayston and colleagues suggest that a fourfold rise in antibody titer between acute and convalescent samples, or a single IgM titer of 1:16 or higher, or a single IgG titer of 1:512 or higher are reasonable criteria for proof of C. pneumoniae infection.94

8 weeks. Grayston and colleagues suggest that a fourfold rise in antibody titer between acute and convalescent samples, or a single IgM titer of 1:16 or higher, or a single IgG titer of 1:512 or higher are reasonable criteria for proof of C. pneumoniae infection.94

A study of 365 adults with acute repiratory illnesses found that 9 (47%) of 19 with serologic evidence of C. pneumoniae infection had bronchospasm at the time of evaluation, and that there was a strong quantitative association of C. pneumoniae antibody titer and wheezing.95 In contrast, a study that attempted to find C. pneumoniae in gargled water specimens of 193 children with respiratory infections was solidly unsuccessful;96 indirect immunofluorescence was negative in all, enzyme immunosorbent assay was negative in all, and PCR detected C. pneumoniae in a total of 3 cases (1.6%). Of those three, all had subacute or chronic bronchitis-like symptoms, and in two the chest x-ray confirmed involvement of the pulmonary parenchyma.96 Part of the problem may be that the nasopharynx, not the oropharynx, is the optimal site for isolation of the organism.

Passive Smoking

Infants exposed to smoking parents have twice the risk of an attack of bronchitis or pneumonia in the first year of life.97

Foreign Body

This was discussed in the preceding section on cough only.

Bacterial Infections

The possible bacterial etiologies of acute bronchitis in children have not been adequately studied. B. pertussis causes a bronchitic syndrome, usually in association with other features, as discussed later. In acute exacerbations in adults with chronic bronchitis, nontypable H. influenzae has been found more frequently than during remissions, and antibiotic therapy directed at H. influenzae usually is helpful.

Children may have bacterial bronchitis complicating sinusitis,98 or more commonly, the symptoms of sinusitis may mimic those of bronchitis.

Bacteria, particularly S. aureus, can cause a purulent tracheobronchitis, which can be mistaken for laryngitis or a foreign body, as discussed in the section on laryngeal syndrome.

Chronic Bronchitis

In children, unlike adults, chronic bronchitis is not adequately defined.98 Practitioner surveys revealed an absence of a widely accepted operational definition.99 In addition to children with asthma or cystic fibrosis,98,99 chronic bronchitis can be proved by endoscopy in children with IgG subclass abnormalities.100

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree