Throughout the course of a woman’s illness, anticancer treatment should be coupled with attention to symptom relief, and personal and family support (1). The development of progressive cancer heralds a point in care where reflection upon the woman’s priorities, and clarification of her goals, should be a priority. Careful exploration of priorities may reveal the importance, for example, of time spent at home, or the need to attend to personal relationships. Ideally, these issues should be raised over time and multiple clinical encounters, rather than suddenly at the time of crisis.

The concept of “parallel care” has been widely advocated (2,3). This concept implies attention to the principles of palliative care (personal and family support, symptom relief, and care planning/death preparation) from the time of diagnosis of a disease with a high likelihood of eventually becoming a fatal illness, for example, advanced ovarian cancer. The alternative approach of introducing palliative care only after anticancer treatments cease has many deficiencies, including potential lack of adequate symptom relief throughout treatment, and perceived abandonment of the patient by the primary physician as care is “handed over” to a new group of healthcare professionals.

The goals of palliative care should be to facilitate comfort, personal rehabilitation, and quality of life in the face of an incurable illness. The patient’s quality of life will be determined by many aspects of her life including her values, her relationships, her sense of self-worth, and health-related matters. A woman can achieve much and indeed may report “quality” in a number of areas, even in the face of progressive illness. The challenge for health caregivers is to create a climate in which such achievements may emerge.

The last phase of life is crucial to the completion of a human life. Patients report that important issues at the conclusion of a fulfilled life include relief of pain and other symptoms, clear decision-making, preparation for death, being able to contribute to others, and being affirmed as a whole person (4–6). During this final phase, it is the responsibility of the medical and nursing professions to facilitate maximum autonomy and dignity, through careful symptom relief, good communication and decision-making, and the development or continuation of a supportive relationship.

Practical Aspects of Palliative Care

The palliative care of a woman with advanced gynecologic malignancy involves several components: assessment, clarification and delineation of therapeutic options, implementation of treatment, evaluation of outcome, continuing review and reassessment, and prognostication. Attention to each of these clinical tasks is necessary for a woman to maximize her possibilities in the final part of life.

Assessment

It is essential to make a comprehensive assessment, which includes listening to the patient’s experience with her cancer, from the prediagnostic phase to the current time. There should be detailing of responses to treatments, side effects experienced, hopes realized, and, conversely, disappointments encountered. The narrative of the illness experience will give information on the patient’s responses and her vulnerabilities and supports. It establishes a shared understanding of what has gone before and is a much more useful therapeutic tool than a checklist approach.

A comprehensive assessment involves at least the following:

1. Ascertainment of the patient’s current symptoms and other problems, in her order of priorities, because only the woman herself can determine which is affecting her quality of life and requiring attention.

2. Clarification of the nature and the extent of the neoplastic process, with careful consideration of any other pathologic process, including comorbidities, that may be contributing to the current problems, or may be likely to contribute in the near future.

3. Clarification of her understanding of her illness and the treatment goals.

4. Delineation of the personal and social context within which the patient is living and from which she may draw support.

5. Elucidation of her current goals—the delineation of such goals and discussion concerning their achievability can do much to enhance a person’s sense of self and hence quality of life.

Involvement of family in the consultation, with the woman’s permission, is often useful as it provides additional understanding of relationships and supports, and may yield other perspectives that have implications for care. The assessment should be regarded as a continuous process, as both the circumstances of the illness and the woman’s priorities are constantly changing.

Clinical Decision-Making

On the basis of a comprehensive assessment, with or without further investigations to elucidate the mechanism of troublesome symptoms, it is normally possible to delineate the reasonable therapeutic possibilities.

The choice between therapeutic options should reflect the patient’s priorities. In general, alternatives involving the least dependence on medical facilities and the least use of the patient’s time, resources, and personal energy should be recommended, particularly in the setting of advanced disease. For example, it would be inappropriate to resort to intravenous (or spinal) techniques for pain relief if oral, transcutaneous, or subcutaneous techniques had not been adequately explored. When decision-making is shared and enacted to realize a woman’s nominated priorities, quality of life is often improved. For example, the fulfillment of a goal to return home may be more important to some than a minor extension of life from a further course of antibiotics.

Careful consideration of relevant antitumor measures (surgery, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy) is always mandatory, because control of the neoplastic process usually offers the best chance of alleviating symptoms. Factors that should be considered when evaluating therapy include the following (7):

1. The stage of disease

2. The likely natural history of the illness with and without intervention, including the likely symptom patterns

3. The burden of investigation and treatment

4. The likely success of the intervention

5. The potential for rehabilitation (physical, psychological, social, or spiritual)

6. The patient’s goals and priorities

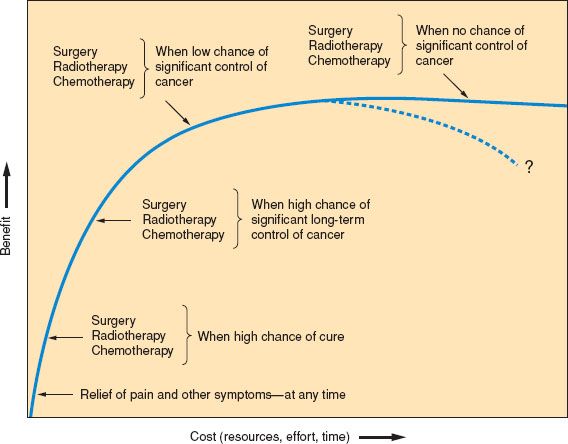

Figure 25.1 Factors to be taken into account when considering further anticancer therapy: Benefit versus cost.

If cost–benefit issues are considered, it is essential to avoid “flat of the curve” medicine. Good symptom relief is almost always high in benefit in relation to cost (broadly considered), whereas anticancer measures may vary in benefit. These matters are represented simply in Figure 25.1.

Clinical decision-making is always undertaken in a context of prevailing values, much influenced by culture, social circumstances, and facts (legal, medical, and resource limitations).

Decisions concerning treatment should usually involve the patient, who should be adequately informed about the advantages and disadvantages of the various options. Such involvement may help the patient to regain control at a potentially chaotic time in her life. Although the patient should share in decision-making, her attending clinician should indicate the course of action he or she favors and ultimately take the responsibility for any intervention, so that a distressing outcome does not engender guilt in the patient and her family. This being said, the physician should not compromise his or her better judgment or conscience in the face of patient or family pressure.

The burden of decision-making is considerable and ways of reaching decisions vary according to social, cultural, economic, and medical contexts. When disagreements arise between patients (or their families) and clinicians regarding clinical decisions, it is often useful to consult within the treating team to determine if a range of views exists among clinicians. A negotiated position between patient and clinician can almost always be reached. If not, a second opinion or a perceived “independent broker” may be useful (8,9).

There are no circumstances that justify a physician’s declaring “there is nothing more that can be done.” A decision not to pursue anticancer treatments, but to focus solely on symptomatic measures, does not indicate nihilism or inactivity. It may reflect authentic clinical wisdom with clear goals of comfort and dignity.

Evaluation of Outcomes

Evaluation of palliative interventions is best performed by the informed patient, although the observations of the medical and nursing staff are important. Evaluations should be performed regularly, at intervals consistent with the clinical goal. Pain measurements may, for example, be appropriately performed each time observations such as blood pressure and temperature are undertaken. For patients with advanced disease when the goals of care are centered on comfort and dignity, monitoring only of those parameters that serve these goals is justified. Formal outcome measures based on subjective criteria, of which there are many examples (10–14), should ideally be introduced into routine clinical practice, with outcomes to be measured commensurate with the patient’s priorities for comfort and for personal objectives.

Discussing Prognosis

Mention should be made of the art of prognostication, because estimates of survival underlie much of the clinical decision-making. There is a considerable body of literature to guide the clinician when formulating a prognosis (15–17). Factors to be considered in such a formulation for patients with advanced cancer include performance status, symptoms and signs relating to nutritional status such as anorexia, and other key symptoms including dyspnea. Biologic parameters, including white cell counts, lymphocyte ratios, and serum albumin also appear to be important (17). These prognostic factors differ from those for a newly diagnosed cancer, such as tumor size and grade (17).

While it may be possible to determine a probability of survival for a particular patient, the communication of this information to the patient and her family requires thought and care. Such a discussion should occur in the context of a supportive relationship, and when the clinician has sufficient time to devote to the task. If the discussion has been prompted by a question, it is important to clarify what the patient has asked, and what has motivated her to ask it. The patient’s understanding of her current situation should be ascertained. It is often helpful to ask the patient what she believes her prognosis to be. The uncertainty of prognostic elements must be explained, and information should be given slowly, at a pace dictated by the patient (9).

A reasonable approach for many patients in the face of a question concerning prognosis is to offer some time boundaries within which death is likely to occur. Such boundaries are useful for determining priorities and for planning medical care to best serve those priorities. Time boundaries do not give a patient or her family an agonizing date around which to focus, nor do they suggest that what is still somewhat uncertain can be predicted precisely (9,18,19).

Symptoms and Their Relief

In general, effective antidisease therapy offers the best chance of good symptom relief if the patient is a “responder,” but the quality of life of a “nonresponder” to chemotherapy may be worse than that of an untreated patient. Expertise in palliative therapeutics should be made available alongside surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, and delivered according to clinical needs, not prognosis (1).

Symptoms are subjective and their presence and severity are not necessarily apparent to the observer. A patient in severe pain may show no signs of distress, yet she may admit upon careful questioning that the pain is almost unbearable. Her expressions of pain will be influenced by cultural and environmental factors and by personal and interpersonal relationships. Accurate assessment of symptoms requires skill, patience, and active, supportive listening. Symptoms vary in their significance for the patient, and anxiety or distress associated with the development of a particular symptom will inevitably have a psychological impact. It is important to give the patient a chance to express her fears and to offer some explanation for the symptom, because this will at least reduce uncertainty.

Symptoms may arise from the tumor itself, from the treatment, and from unrelated causes. Symptoms may precede signs or objective evidence (x-ray or scans) of disease. An example is the development of leg pain from lumbosacral plexus infiltration, which may herald recurrent cervical cancer. Imaging may fail to demonstrate a lesion suspected on the basis of symptoms, but the pain needs treatment even while awaiting a definitive diagnosis. Waiting for objective signs may be disastrous in certain circumstances, such as in the early diagnosis of remediable spinal cord compression.

There is now considerable literature concerning the understanding and therapy of major symptoms in cancer, and attention is given here to those seen more commonly, with emphasis on practical considerations.

Pain Management

Pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage.” Thus pain is subjective—all pain is “in the mind.” Psychological factors influence the perception of pain. Pain is the experience of a person, not a part of the body, and changing the experience of a person is a major challenge. Effective pain management is dependent upon understanding and delineating the pain mechanisms involved, and prescribing medication based upon these mechanisms. Controversies relevant to gynecologic practice remain, not least being the global inequity in access to pain relief for women with gynecologic cancer (20).

Pain in gynecologic cancer presents in many forms and may occur at any stage in the illness. It may be caused by the disease and its treatment. Pain caused by treatment (e.g., radiation therapy) requires as close attention as that caused by tumor. Many guidelines for the assessment and treatment of cancer pain have been published, including those by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the European Society of Medical Oncology (21,22). The following simple steps provide a practical approach in the face of the complexity of recent research and practice (23).

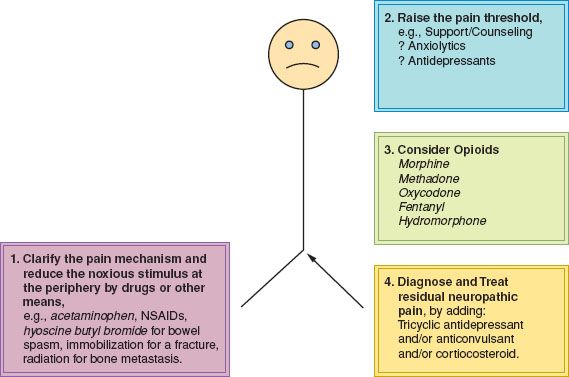

Pain management must begin with a diagnosis of the likely mechanism of the pain at this site and at this time. The mechanism of pain can usually be diagnosed clinically. The history should include the mode of onset, characteristics, distribution, aggravating factors, trends over time, and response to therapeutic endeavors thus far. Therapeutic approaches vary according to the mechanism that is operative. Following diagnosis of the pain mechanism, management may proceed according to the following four steps (Fig. 25.2):

1. Reduce the noxious stimulus at the periphery.

2. Raise the pain threshold.

3. Consider and use appropriate doses of opioid drugs.

4. Recognize residual neuropathic pain and treat it correctly.

Such steps should be considered in order, but measures relating to all four steps may be instituted simultaneously if the clinical circumstances dictate.

Step One: Reduce the Noxious Stimulus at the Periphery

This step demands an adequate understanding of the mechanism of the pain stimulus in the individual patient. Pain in patients with gynecologic cancer is most commonly due to soft tissue infiltration, bone involvement, neural involvement, muscle spasm (e.g., psoas spasm), infection within or near tumor masses, or intestinal colic. Pain felt in the back needs particularly careful consideration, because the causes are many and the treatments are diverse.

Figure 25.2 Schema for the approach to pain management. NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Specific measures to reduce the noxious stimulus may include reducing size of the tumor mass with radiotherapy, treating an unstable fracture by surgical fixation, or performing a peripheral nerve block. Peripherally acting drugs should be used irrespective of these specific therapeutic measures.

Bone metastases frequently cause inflammatory changes with release of inflammatory mediators, including prostaglandins. When the pain is clearly arising from bone metastases, the use of drugs that interfere with prostaglandin synthesis (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]) is logical. These drugs should be avoided or used with caution in patients who have a history of peptic ulceration, excessive alcohol consumption, bleeding diathesis, renal impairment, or known allergies to aspirin or related drugs. Where the use of NSAIDs is precluded, acetaminophen (paracetamol) is a useful alternative. While its mechanism of action is yet to be fully elucidated, clinical utility suggests some peripheral action. Evidence for its benefit is yet to be established in large studies (24). Acetaminophen is fairly well tolerated and safe, but it should be used in reduced dosage in patients with impaired liver function.

Peripherally acting drugs such as acetaminophen and NSAIDs are useful for pain arising in nonosseous sites and for postoperative pain (25). They should rarely be omitted from analgesic regimens, even in bedbound patients. Rectal preparations may prove useful in patients who derive clinical benefit but are unable to take oral drugs.

Muscle spasm requires muscle relaxants and gentle massage. Psoas muscle spasm, usually resulting from direct tumor infiltration, is not infrequent in gynecologic cancer (26). Psoas muscle infiltration should be suspected if there is pain in a lumbosacral plexus distribution associated with difficulty achieving full extension of the hip. While radiation therapy is being considered or applied, relief can usually be achieved by careful adherence to the outlined principles, but will not be adequately managed by opioids alone. Acetaminophen and NSAIDs, an oral opioid (such as oxycodone), and a laxative must be supplemented by a drug that is active against spasm in skeletal muscle, such as diazepam. Steroids should be considered in the short term (e.g., dexamethasone 2 to 4 mg daily). Polypharmacy is justified to relieve pain in the malignant psoas syndrome. If the pain does not respond to these measures, specialist help must be sought (27).

Regional blockade with a local anesthetic and neurolytic techniques may be a useful measure to reduce the peripheral noxious stimulus if the area of pain is circumscribed and attributable to an accessible peripheral nerve, such as pain in the intercostal region.

Step Two: Raise the Pain Threshold

All persons should be considered to have a threshold above which they will be troubled by pain. It is useful to consider the threshold as “one’s sense of mastery of a situation.” Such a threshold is dynamic and may be influenced by many factors. The threshold for pain may be raised by explanation, comfort, care, concern, diversion, and various forms of relaxation. Similarly, the threshold may be lowered, or a patient’s sense of mastery may be affected negatively by sleeplessness, depression, anxiety, uncertainty, loneliness, and isolation. Threshold issues in general require a nonpharmacologic approach.

A wide range of strategies exist to facilitate coping with pain and simple measures, such as explanation of, for example, the likely cause of pain, should be available to all patients. The diagnosis of a disturbed threshold in an individual patient is difficult, but the narrative approach to assessment of the patient will give clues. As the patient tells the story of her diagnosis, treatment, and the pattern of her pain, she imparts information about the cancer and about herself, and excessive distress can be readily perceived. Many complementary therapies, such as massage and meditation, assist in the relief of pain and it is likely that their benefits stem from enhancing a patient’s sense of mastery.

Occasionally, anxiety and depression are so marked that the patient is impeded in her attempts to relate to her loved ones or to come to terms with her disease, and may manifest as ever increasing pain. In such circumstances, a formal psychiatric consultation may be of assistance and anxiolytics or antidepressants may prove helpful. In general, threshold issues, including extreme anguish, feelings of futility, loss of sense of meaning, personal guilt, and other forms of spiritual pain, require a nonpharmacologic approach, with help from skilled counselors, pastors, and, above all, those people who are closest to the patient.

Pain and suffering are related but distinct. Suffering is described as a sense of impending personal disintegration (28). In common parlance, there may be a sense of being about to “go to pieces.” Suffering may be triggered by poorly controlled symptoms, perceived loss of dignity, loss of a sense of control or autonomy, fear for the future, and loss of a future. Pain may be the main cause of suffering, or a manifestation (through threshold shifts) of suffering, with the language of suffering expressed through pain.

If suffering is defined as a sense of impending “personal disintegration,” then the response to suffering should be “reintegration.” Such reintegration may be most assisted by others who have skills in the dimension of care that is focused on existential issues; these may or may not be related to religious matters. But every doctor has the responsibility and privilege to be aware of such dimensions of care, to provide the “space” for patients to consider their existential concerns (notably to ensure that symptoms are well controlled), and to take time to be informed about current reflections on this area (29).

Step Three: Precise and Appropriate Use of Opioid Drugs

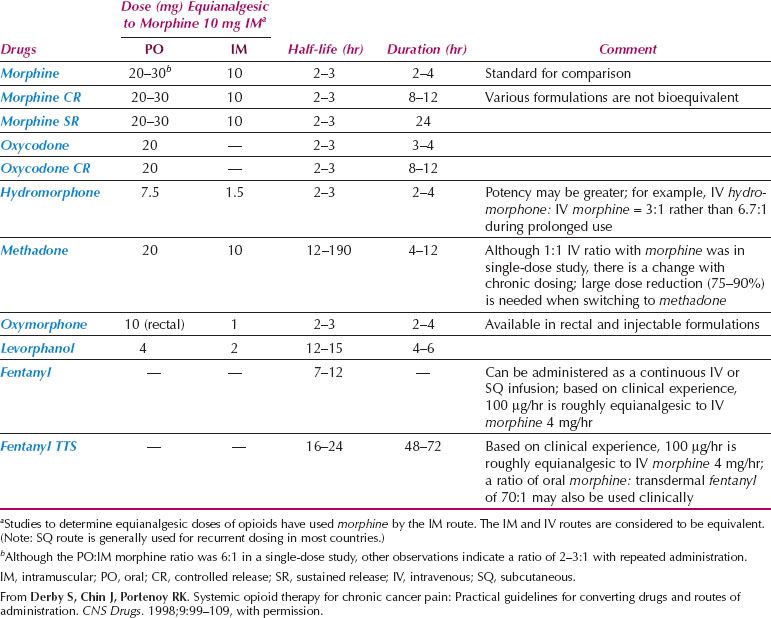

There is abundant literature on opioid use to supplement peripherally acting analgesics, with a range of opioids available (30). Despite the initiatives of the World Health Organization, there are still difficulties obtaining opioids for medical use in some countries (31). A variety of opioids is available and the principles of choice need to be understood (Table 25.1) (30). In practice, low-potency opioids such as codeine or dextropropoxyphene, or high-potency opioids such as morphine, are combined with peripherally acting drugs such as acetaminophen or aspirin. Low- and high-potency opioids should not be given concurrently, but a change from one opioid to another may be justified (32). While equianalgesic dose calculation tables assist if changing prescription from one opioid to another (Table 25.1), these should be used only as a guide, with clinical surveillance essential to ensure neither toxicity nor too little effect is achieved. When calculating an equivalent dose of an alternative opioid, conservative dosing is recommended. Doses that are 25–50% of the calculated dose may be appropriate, with regular assessment following the change (33). While for many morphine remains the preferred high-potency opioid, consideration is increasingly being given to alternative high-potency opioids such as oxycodone and hydromorphone, if available (30,34). Local availability and affordability should inform the choice of opioids.

Table 25.1 Opioid Analgesics Used for the Treatment of Chronic Pain

Regardless of the choice, opioids should be given at regular intervals in accordance with the half-life of the drug concerned, rather than haphazardly in response to a severe pain stimulus. Doses of opioid drugs should be carefully titrated against response and side effects.

A number of oral opioids including morphine, oxycodone, and hydromorphone are available in two forms: an immediate-release preparation that reaches a peak within 30 minutes of ingestion, and a sustained release preparation that typically takes several hours to reach peak concentrations (35). As a general rule, for a patient not previously taking opioids, initial prescribing should involve regular dosing with an immediate-release preparation as a “dose-finding” exercise. This allows rapid escalation or reduction of dose according to clinical response. When effective doses are reached, the woman may be converted to a convenient, long-acting preparation with the dose prescribed based upon her daily requirements. Any long-acting medication should be given with an immediate-release opioid available, should episodes of “breakthrough” pain occur.

Some types of pain are only partially responsive to opioids (27), including pain caused by nerve irritation, extreme muscle spasm, incident pain (i.e., pain exacerbated by a particular activity such as movement), or pain that is heightened by unaddressed anguish. Even in these circumstances, for the patient with cancer, opioids remain “partially effective” and should be introduced alongside, for example, neuropathic pain agents, and carefully calibrated to ensure that optimum benefit is achieved while minimizing side effects (36).

Morphine

Immediate-release morphine is best given every 4 hours, with a double dose (or 1.5 times the standard dose in the frail) at bedtime, and a break of approximately 8 hours overnight to permit sleep for both patient and caregiver. A reasonable starting dose of oral morphine in a patient with severe pain not already on an opioid drug would be 10 mg in an average sized patient, or 3 to 5 mg in a frail or very elderly patient. The original dose should be repeated in 1 to 2 hours if there is inadequate relief of pain. Over the next 24 to 48 hours, dose finding should be undertaken by prescribing regular doses every 4 hours, together with one or two “breakthrough” doses, equal to the standard dose. The correct dose may range from 2 mg to more than 100 mg every 4 hours, but most patients should need less than 50 mg every 4 hours.

When the daily dose requirement has been established, it can be converted to a sustained-release formulation, maintaining supplemental breakthrough doses of the immediate-release preparation. For example, a patient taking 20 mg oral morphine sulfate mixture every 4 hours should be converted to 60 mg sustained-release morphine each 12 hours, with additional breakthrough doses of 20 mg of morphine sulfate mixture if required.

Sustained-release morphine (or other sustained-release opioids) should not be used in patients with (i) uncontrolled or unstable pain; (ii) extensive upper abdominal or retroperitoneal disease that is likely to interfere with gastrointestinal motility; or (iii) fecal loading or impaction. Subcutaneous morphine is a better choice in such circumstances.

If parenteral morphine is essential, the subcutaneous route is appropriate, either with intermittent injections through an indwelling butterfly needle every 4 hours or with a continuous infusion through a battery-driven syringe driver or pump. When a patient is constipated or has a bowel obstruction and pain is not well controlled with simple analgesics such as acetaminophen (paracetamol), 4-hourly subcutaneous morphine is useful for both pain relief, and calibration of the required dose of morphine. After the constipation has been relieved, the subcutaneous 24-hourly dose may be readily converted to oral morphine. The intramuscular route is rarely advantageous.

In general, a parenteral dose of one-half or one-third of the oral dose appears equianalgesic (37). If oral or subcutaneous morphine is efficacious but the side effects are troublesome, the epidural route may be occasionally necessary, but a change to another oral or parenteral opioid should normally be tried first.

Intravenous morphine infusions, although sometimes useful (e.g., in a patient with peripheral circulatory failure), do not offer significant advantage over the subcutaneous route for most patients, and generally ensure greater complexity and disruption for the patient. In the setting of rapid dose escalation of intravenous morphine, cessation of the infusion and resumption of appropriate subcutaneous doses every 4 hours may be helpful. Simultaneously, it is important to review other aspects of management, such as the possible need for NSAIDs or drugs relevant to neuropathic pain, and to pay appropriate attention to psychological factors.

The efficacy of the regular dosing approach to morphine administration may depend on the contribution of an active metabolite (morphine 6-glucuronide), which, like morphine, is a powerful mu receptor agonist. Hepatic impairment, if severe, interferes with morphine metabolism to glucuronides. Renal impairment, even if only moderate, interferes with excretion of the active metabolites. In both these circumstances, dose reduction is essential. In a patient with renal impairment, it may be necessary to extend the dose interval from 4 to 8 or even 12 hours. The use of morphine in a patient with marked renal impairment is very complex, and an alternative opioid that does not have active metabolites such as fentanyl may be a better choice (30,38).

Some physicians, nurses, and patients continue to harbor misconceptions about the use of morphine. When morphine is to be commenced, counseling should address three issues to counteract widely held fears:

1. The use of morphine with careful dose finding and monitoring does not, in the vast majority of patients, lead to addiction (although physical dependence, a separate issue, occurs). Specialist help is needed to use morphine appropriately in current or former intravenous heroin users.

2. The introduction of morphine does not mean that the patient is actually dying, but rather that morphine is the most appropriate opioid at that time. It is the type of pain and its severity, not the prognosis of the patient, that dictates whether an opioid should be introduced. Morphine, correctly used, does not hasten death.

3. The introduction of morphine does not mean that it will be ineffective at a later stage in the illness, when the situation may be worse. Morphine does not lose its effectiveness, but increased doses may be needed later in response to tumor progression.

Use of Alternative Opioids

Other potent opioids should be considered when (i) pain persists despite careful drug calibration; (ii) unacceptable side effects persist (e.g., cognitive impairment, nausea) despite careful drug calibration; or (iii) drowsiness or toxicity occurs at levels of the drug required to control the pain. In these circumstances, after reconsideration of the pain mechanism and the other analgesic steps, an alternative opioid should be considered. Availability varies from country to country, but gynecologic oncologists should become familiar with a narrow range of opioids (Table 25.1). In countries where there is wide availability and affordability of opioids, the choice may depend upon the preferred route of administration (oral versus transdermal). Oxycodone (available as immediate-release tablets, suspension, sustained-release preparations, parenteral, and suppositories) is somewhat more potent (20–50%) than morphine. Oxycodone is most often used in a dose of 5 to 20 mg every 4 to 6 hours. Some patients tolerate oxycodone better than morphine at the same dose, and vice versa. In general terms, however, the side-effect profile is similar (30).

Methadone is occasionally useful, particularly for those who appear to have pain that is more difficult to control (30,39). Its long half-life is sometimes disadvantageous, particularly in the elderly, and its sedative action may outlast its analgesic activity. It has mechanisms of action that differ slightly from those of morphine, being reported to have both opioid receptor activity and activity on the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor pathways (40). Therefore, methadone may be occasionally useful when higher doses of other opioids have been reached with only a partial or inadequate response. Conversion from morphine to methadone may be difficult, with subsequent dose reduction frequently required—specialist assistance is recommended (41). Methadone has a similar side-effect profile to morphine.

Hydromorphone is another alternative. Like morphine, hydromorphone is a mu agonist but with far greater solubility. It can be administered orally, intravenously, and subcutaneously with a duration of action and half-life similar to morphine. Its high potency allows smaller volume injections (42).

Fentanyl offers a transdermal route of administration, enabling continuous administration of a short-acting opioid (43). Dose calibration should usually occur with morphine, oxycodone, or subcutaneous or intravenous fentanyl before transdermal therapeutic system (TTS) fentanyl is applied. The patch forms a depot of drug in the dermis, resulting in a 12- to 48-hour delay before maximum plasma concentration is reached. After TTS removal, the terminal half-life is approximately 13 to 25 hours (44). In practice, this means that when the patch is applied, the immediate-release drug should be continued for at least 12 hours. If adverse effects develop, they will continue after TTS fentanyl removal and the patient should be monitored closely. When a patient who is using TTS fentanyl experiences an increase in pain, a short-acting opioid should be given concurrently and the dose used to calculate the extra opioid requirement, which can then be incorporated into the TTS fentanyl dose.

TTS fentanyl is an attractive option for many patients because of the convenience of the delivery system and the slightly less troublesome constipation compared with morphine (43). Dose escalation is commonly observed, possibly related to the short half-life of the drug. If very rapid dose escalation occurs (without evidence of rapid tumor progression), a change to another opioid may be wise and less expensive.

Buccal and transmucosal fentanyl citrate preparations provide an immediate-release fentanyl formulation for breakthrough pain that offers rapid onset of analgesia, and similar or improved response compared with immediate release morphine (45). Expense may dictate that traditional preparations are still chosen.

When using TTS fentanyl, it must be remembered that:

• It is a delivery system useful only for chronic pain. It may be hazardous for unstable pain and should not be used after surgery or in rapidly changing pain states.

• Because of depot formation in the dermis, a delayed response occurs that is particularly important in toxicity or overdose situations.

• A short-acting opioid should be available for breakthrough needs (e.g., immediate-release morphine, or transmucosal fentanyl citrate).

Meperidine (pethidine) is of very little value in palliative care. It is addictive, has poor oral bioavailability, and a short half-life, requiring administration approximately every 2 hours. At high doses (>1 g/d) or when renal failure is present, the metabolites lead to neurotoxicity, including delirium, agitation, and seizures. If a patient is already receiving meperidine subcutaneously or intramuscularly, conversion to morphine can be achieved with approximately 10% of the meperidine dose given as subcutaneous morphine, or 30% of the meperidine dose given as oral morphine every 4 hours.

Side Effects of Opioids

In general, the side effect profile of all opioids is similar, though there may be individual variation in response, particularly around the development of adverse effects. It is likely these individual variations result from cytogenetic differences, though this is an emergent field of knowledge (46). Side effects can be avoided, or at least minimized, in large part by precise prescribing. Although there are some side effects that are almost invariable, such as constipation, individual variation in side-effect profile may be used to advantage by substituting an alternative opioid (30,41).

Constipation occurs in most patients, and prophylactic laxatives should be prescribed. A reasonable laxative prescription would be senna and sodium docusate tablets twice daily. Fecal impaction, much more likely if opioids are given without a laxative, may cause a variety of distressing symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, pelvic pain, or confusion. TTS fentanyl is slightly less constipating than slow-release morphine (47).

If opioid-induced constipation persists after treatment with the usual laxatives, subcutaneous methylnaltrexone, the opioid antagonist, may be considered, though bowel obstruction should be ruled out prior to administration (30). Compounds have been developed which combine oxycodone with prolonged release naloxone (which displays local, antagonist effects on opioid receptors in the gut wall and has negligible systemic bioavailability) in an attempt to minimize the constipating effects of opioids (48). These offer some benefits in terms of convenience, but have limitations for those patients with higher opioid dose requirements as the fixed ratio between compounds means that the opioid dose cannot be escalated beyond the ceiling dose of methylnaltrexone.

Nausea and vomiting may occur in association with opioid therapy as a result of gastric stasis, stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone, or constipation. Nausea is particularly common when opioids are commenced or when the dose is changing, but tolerance to this side effect develops in many patients within 48 hours. Suitable antinauseants such as metoclopramide, 10 mg four times daily or haloperidol, 0.5 to 1.5 mg twice daily, both given orally or subcutaneously, should be available if required. Regular prophylactic antiemetics should be prescribed for at least the first 48 hours if the patient is very anxious, or if there is a history of opioid-induced nausea or vomiting. If vomiting persists, an alternative opioid should be substituted. All opioids may cause nausea, but there appears to be individual but unpredictable variability in response between the drugs. The evolving field of pharmacogenetics may provide some ability to predict an individual’s response (46).

The prescription of opioids should be individualized. As with a number of other medications (e.g., digoxin), if the dose prescribed is inadequate, there will be no clinical response. If the dose is too high, the patient will enter a toxic range and will develop dose-related side effects. The dose-related side effects of opioids include drowsiness and delirium. At the extreme end of the toxic range is respiratory depression, with reduced respiratory rate. This is rarely seen in chronic opioid prescribing, and not before the patient has exhibited earlier signs of toxicity such as drowsiness and delirium.

If drowsiness develops and persists for more than 24 hours, the opioid level is probably above the therapeutic range for that patient. Other causes of drowsiness should be excluded, such as sedating drugs or hypercalcemia, and a dose reduction of opioids should be considered.

The development of confusion or hallucinations generally indicates either excessive dosage, or excessive accumulation such as may occur in renal failure, or occasionally, an idiosyncratic reaction. Hydration—orally, subcutaneously, or intravenously—may assist in eliminating troublesome metabolites while dose reduction is undertaken. If the pain is not well controlled in the presence of drowsiness or confusion, another approach is usually required, such as an alternative opioid or an alternative route of administration (e.g., spinal).

Pruritus is troublesome for a small number of patients taking morphine because of its histaminogenic properties. It usually settles within 48 hours and can be managed with judicious use of promethazine. Pruritus is rarely reported for other opioids. Anticholinergic side effects of opioids are usually not troublesome.

Tolerance to opioids may be a significant clinical problem if the drug is not introduced and calibrated correctly. When opioids are used correctly, increased requirements during the course of an illness usually signify an increase in the noxious stimulus because of disease progression, rather than a reduction in the effectiveness of the analgesic. Ketamine, a drug used traditionally in anesthesia, has been used occasionally to reverse opioid tolerance for some patients with pain (49).

Step Four: Recognize Neuropathic Pain and Treat Correctly

Neuropathic pain is a term used to describe those pain syndromes in which the pathophysiology is related to aberrant somatosensory processes that originate with a lesion in the peripheral or central nervous system. Neuropathic pain is a frequent complication in gynecologic cancer, especially in advanced cancer of the cervix. It may be caused by tumor infiltration (notably lumbar plexopathy), or occasionally may result from therapeutic interventions. It may be flashing or burning in nature, but is often an unpleasant ache in an area of altered sensation corresponding to a peripheral dermatome.

When pain is neuropathic in origin, Steps 1 to 3 should usually be supplemented by a tricyclic antidepressant, anticonvulsant, or a corticosteroid (36). An agent should be chosen from a particular class of drug, such as an anticonvulsant (e.g., gabapentin). The choice should be based on tolerability, comorbidities, and any associated symptoms such as anxiety. If ineffective, an alternative agent from that same class should be trialed before moving to another class such as antidepressants (50). In general, medications should be started at low doses and gradually increased as tolerated, but treatment of severe neuropathic pain is a challenge (30,50).

Other Dimensions of Pain

Breakthrough pain is defined as an episode of worsening pain when the background pain appears to be controlled by the regular analgesia (45). Breakthrough pain should be distinguished from end of dose failure, where the long-acting opioid dose is insufficient to provide analgesia until the next regular dose is due. In general, a short-acting opioid, either immediate-release oral opioid or buccal or transmucosal fentanyl, should be made available to cover these breakthrough episodes (30). The effective dose required for relief of breakthrough pain is not necessarily related to the baseline scheduled medication (45) so therapy should be initiated using low doses with dose titration thereafter as necessary. For those using an oral opioid, clinical experience has revealed that 1/10th to 1/6th of the 24-hour scheduled medication total dose should be safe.

Ketamine, when used in subanesthetic doses, has been reported by some to be useful in the management of very complex pain, both somatic and neuropathic in origin (49). Ketamine acts as an antagonist to the NMDA receptor system, a system frequently activated in refractory pain states, when high doses of opioids appear ineffective. Small trials and case series have suggested that low doses of infusional subcutaneous ketamine can reduce opioid tolerance and improve analgesia (51). A multisite study investigating ketamine in refractory cancer pain revealed that ketamine was equivalent to placebo in analgesic response, and held substantially greater toxicity (52). Further studies are underway, but it should only be used in consultation with palliative medicine or pain specialists, because of the significant side effects, such as hallucinations.

Spinal analgesia may benefit a carefully selected small group of patients. Anesthetic opinion should be considered for patients who continue to have pain despite an adequate trial of analgesia according to Steps 1 to 4, or for those who have very severe incident pain, that is, pain associated with a particular activity, such as weight bearing (53). The ongoing capacity of the care system to support the spinal analgesic delivery devices (implantable pumps, intrathecally inserted Port-o-cath devices, or other systems) must be considered prior to implementation. For some, the delivery of spinal analgesia requires ongoing hospitalization, because community supports are unavailable. Expense may be very significant.

Pain Prognostic Score

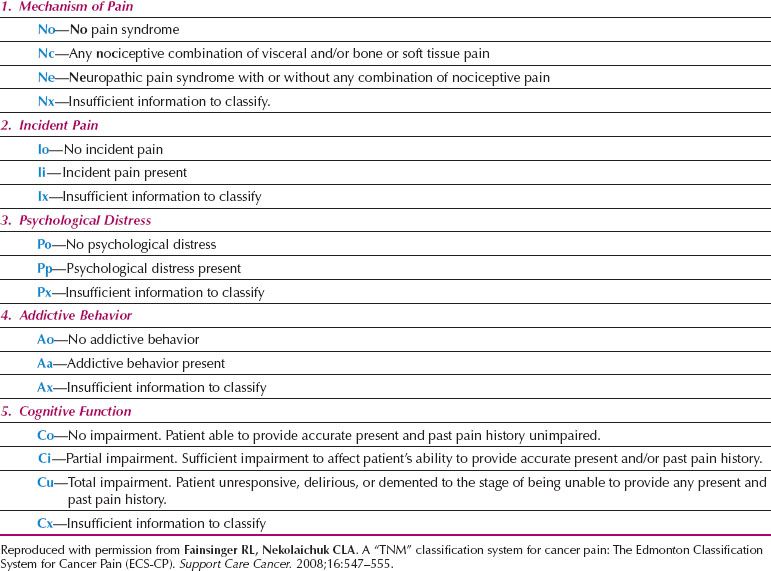

The recognition that patients with cancer-related pain vary considerably in their responses to standard analgesic regimes has led to the development of a classification system for pain. Based on the TNM classification system for cancer, this represents an attempt to group pain such that appropriate comparisons and predictions of outcome can be made (Table 25.2) (54). According to this classification, the presence of particular pain mechanisms, incident pain (pain during an activity), psychological distress, addictive behavior, and disturbed cognitive function are all associated with increasing complexity of pain management.

Special Considerations in Pain Management

The Patient with Renal Failure

In patients with renal impairment, NSAIDs should be avoided, as they will frequently worsen renal function, while the use of morphine will result in the accumulation of active morphine metabolites. Therefore, if prescribing morphine, a dose reduction may be necessary and, more importantly, the interval between doses should be extended. Use of alternative opioids such as fentanyl or methadone, which are reported not to have active metabolites, is recommended (38).

Allergy to Opioids

Many patients will report that they are allergic to opioids, or have such an allergy recorded on their medical record. A detailed exploration should be undertaken of the event when an allergy was first cited. Frequently, the original event was the development of nausea and vomiting when opioids were administered. Sometimes it is the report of a confusional state, particularly in the setting of postoperative analgesia. Neither of these constitutes a true allergic reaction, which is extremely rare. If it is suspected, palliative care expertise should be sought.

The Patient with Reduced Motility of the Gastrointestinal Tract

The patient who has a hypomotile gastrointestinal tract, most commonly seen in patients with disseminated ovarian cancer, may have impaired peristalsis and impaired absorption of oral medication.

Motility may be further impaired by drugs such as 5HT3 blockers (e.g., ondansetron), which, although very effective antinauseants for patients undergoing chemotherapy, may induce constipation. Consideration should be given to delivering analgesics via an alternative route, such as transdermally (fentanyl) or, for the very ill, subcutaneously. Similarly, alternative routes of analgesic administration should be sought for the patient with established fecal loading.

Table 25.2 Edmonton Classification System for Cancer Pain

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree