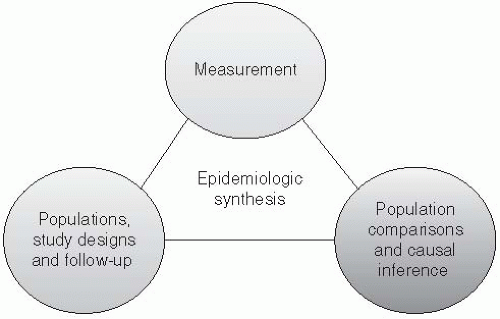

Who is to be studied? Epidemiologists study diseases in populations of individuals. While studies of entire populations may be of interest, typically only a sample of individuals contributes to an epidemiologic evaluation, selected according to specific study designs.

Which data will be collected? Observing the occurrence of diseases and their determinants requires measurement for purposes of constructing measures of disease occurrence.

Which inferences will be made from the analysis? Epidemiology, as the study of the distribution, determinants, and control of disease, is predicated on the fact that disease occurrence in humans does not occur at random. Epidemiologic evaluations play an important descriptive role in characterizing diseases among populations. When evaluating the determinants of diseases, epidemiologic evaluations typically require comparisons of populations for making causal inferences.

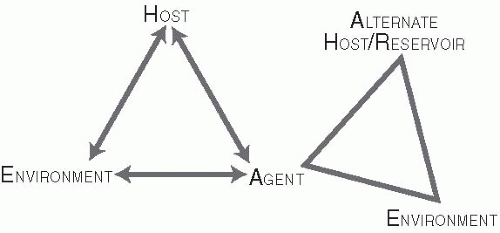

Host. Human hosts differ in susceptibility to infections because of genetic, environmental, behavioral, and other characteristics. Major epidemic diseases, such as malaria, tuberculosis, smallpox, and plague, have led to selective genetic changes in human populations. For example, the evolution of several genetic mutations among Africans and Asians has resulted primarily from the selective pressure of hyperendemic malaria. Sickle hemoglobin, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, thalassemia, hemoglobin C, and hemoglobin E may be disadvantageous in homozygous individuals, but these traits have evolved in certain populations because they confer significant protection from malaria in heterozygous individuals.1

Agent. The agent constitutes the infecting pathogen (e.g., virus, bacterium, parasite, or fungus). Agents have certain characteristics that influence their infectivity. For example, one important characteristic of a pathogen is its escape mechanism, such as the evolution of resistance to antibiotics and antiviral

therapies. This capability is recognized as a growing threat to public health and was presciently predicted in 1945 by the discoverer of penicillin, Sir Alexander Fleming, who said, “The greatest possibility of evil in selfmedication is the use of too-small doses, so that, instead of clearing up the infection, the microbes are educated to resist penicillin and a host of penicillin-fast organisms is bred out which can be passed on to other individuals.”2

Environment. The environment constitutes the setting in which transmission occurs. It is important to understand and characterize the environment in which transmission occurs and to be aware of environmental factors that may facilitate the agent’s survival or infectivity. It is not difficult to envision the role of environment for some agents, such as hookworm, where soil humidity, temperature, and other soil characteristics can influence the development of infectious Ancylostoma duodenalae larvae. However, the environment is also important in the transmission of airborne viruses, such as influenza and varicella, because it affects the length of time that the viral particles remain infective as an aerosol. The winter environment in temperate climates also facilitates transmission of influenza by bringing people indoors. Conversely, influenza epidemics have been interrupted by extreme cold weather that has forced schools to close, thereby interrupting transmission among children and introduction of the virus into the home.3

might include demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, race/ethnicity), socioeconomic characteristics (e.g., education, income), or biologic factors (genetics).

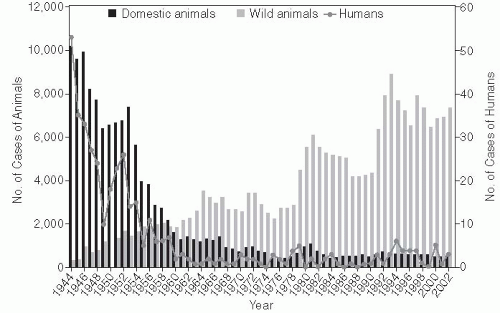

cave and protected from bites and even insect transmission but were exposed to the air in the infected cave. After several animals developed rabies during this exposure, the classic concepts of rabies transmission were challenged.5 This hypothesis was confirmed in additional laboratory studies that showed rodents could be infected by aerosol inoculation.6, 7 This route of infection was further explored by a review of case reports of rabies in the United States between 1980 and 1996, which found that, in the majority of human cases, there was no clear documented evidence of a bite; however, the reports also suggested that an unreported or undetected bite remained the most plausible hypothesis regarding route of transmission.8 The control of rabies in domestic animals in the United States has resulted in fewer human cases, with a higher proportion of cases being attributed to wild animal exposures. These exposures are not as readily recognized as rabies risks, so preventive vaccination and postexposure prophylaxis may not be initiated. Reports of individual cases continue to provide information that contributes to our general understanding of the transmission of rabies.

girl in Cali, Colombia. A third patient, a 15-yearold boy in Brazil, was also successfully administered this treatment protocol, after receiving postexposure prophylaxis.14

Table 3-1 Sources of Human Exposure to Rabies in the United States | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

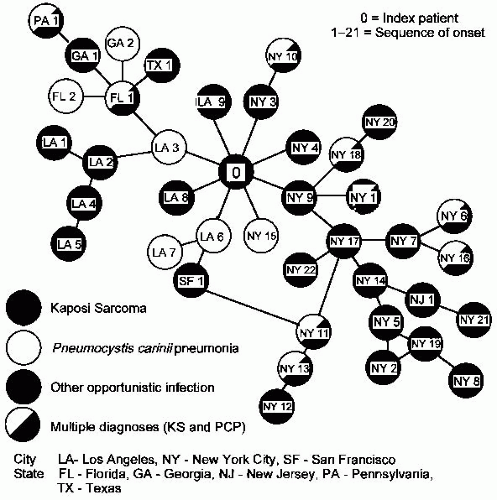

of AIDS patients, which was reported early in the epidemic and prior to the identification of HIV, is described next.

Figure 3-5 Sexual contacts among homosexual men with AIDS. Each circle represents an AIDS patient. Lines connecting the circles represent sexual exposures. Indicated city or state is place of residence of a patient at the time of diagnosis. “0” Indicates Patient 0. Reprinted from the American Journal of Medicine, Vol. 76, D. Auerbach et al, Cluster of Cases of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome Patients linked by Sexual Contact, pp. 487-492, © 1984, with permission from Excerpta Medica Inc. |

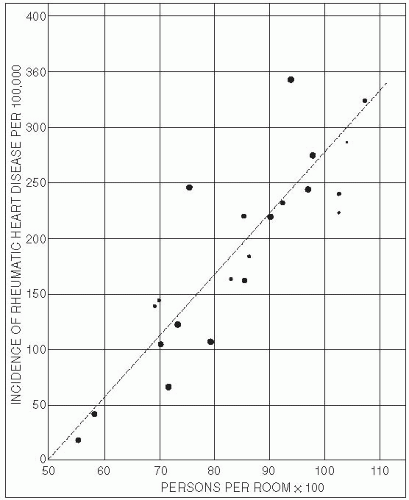

or community-wide surveys of exposure frequencies and disease rates, which can often be obtained inexpensively. Ecologic studies also allow for comparisons where the range of exposure in one particular population may be too narrow to correlate with a disease outcome at the individual level. For example, the association of vitamin A deficiency with an infectious outcome would be difficult to evaluate in a population consisting of only vitamin A-deficient individuals. Alternatively, an ecologic study comparing infection outcomes across populations with varying prevalence of vitamin A deficiency would permit a better assessment of the correlation. Similarly, studies of the relationship between infectious agents and unusual outcomes—such as the liver fluke Opisthorchis viverrini and bile duct cancer, and Helicobacter pylori and stomach cancer—can be strengthened by ecologic data from populations with widely varying levels of infections and cancer.

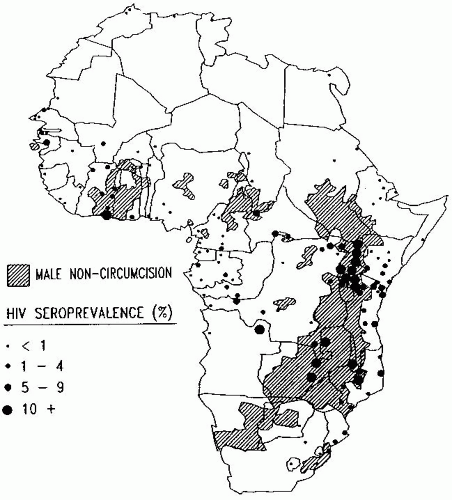

serve as an entry point for HIV. The foreskin may also trap HIV in a warm moist environment, allowing more time for infection to occur. Given these factors, it is not surprising that circumcised men have been found to have lower rates of sexually transmitted diseases.21

Figure 3-7 Map of Africa showing political boundaries and usual male circumcision practice, with point estimates of general adult population HIV seroprevalence superimposed. Reproduced from Moses et al., Geographical Patterns of Male Circumcision Practices in Africa: Association with HIV Seroprevalence. International Journal of Epidemiology, Vol. 19, pp. 693-697. © 1990. By permission of Oxford University Press. |

associated with religion may thus partly explain the protective effects of circumcision among Muslims.23

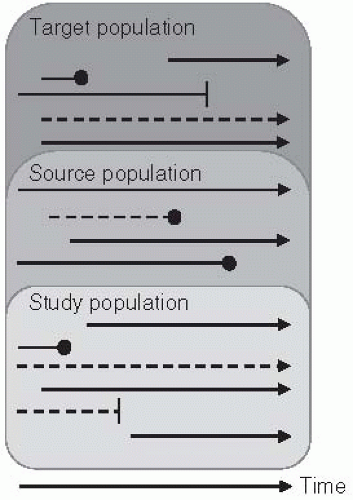

Selection of the study population from the target and source populations. As noted previously, there are usually individuals who are part of the target population but who are outside the study population. Thus the manner in which individuals are selected (or self-select) for participation into the study population is an important consideration in evaluating the inferences of a study.

Determination of time metric and follow-up. The choice of an appropriate metric for conceptualizing the study population moving through time is an important design consideration. Typically, studies are described in terms of the calendar time during which individuals are enrolled and followed. Keep in mind, however, that time can be defined by any number of measures, such as chronological age, biological life stages (e.g., before or after menopause), or other events (e.g., jobs, marriage, retirement).30

Exposure assessment. In the simplest studies evaluating the link between a particular exposure (e.g., “exposed” and “unexposed,” illustrated as solid and dashed lines, respectively, in Figure 3-3) and outcome, it is important to determine whether and how exposure may change over time. Some exposures may be unchanging (“fixed”) within an individual (e.g., genetics). Others may be time varying but may change in different ways. For example, some infectious exposures may be transitory and recurrent (e.g., influenza), whereas others are persistent and lifelong once acquired (e.g., HIV). When exposures can change, an important aspect of the study design is the time when they are assessed. It is vital that they are measured at a relevant time point so that they can be temporally linked to a disease outcome.

Outcome assessment. At the end of the period at risk, some individuals in the study population may develop the disease of interest (Figure 3-3, circles). Like exposures, some disease outcomes may be transient and recur; others are lifelong or defined that way in the analysis (e.g., defining a disease outcome as the first occurrence).

adherence in a standardized manner is aided by guidelines such as the CONSORT statement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree