- The prevalence of erectile dysfunction (ED) in men with diabetes increases with age and is about 35–50% overall.

- Penile erection occurs as a result of engorgement of the erectile tissue following vascular smooth muscle relaxation in the corpus cavernosum mediated by nitric oxide (NO), which is derived from both parasympathetic nerve terminals and the vascular endothelium.

- ED in diabetes is largely brought about by failure of NO-mediated smooth muscle relaxation secondary to endothelial dysfunction and autonomic neuropathy.

- ED is an early indicator of endothelial dysfunction and a marker of increased cardiovascular risk.

- Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors are first-line treatment and act by inhibiting the breakdown of cyclic guanosine monophosphate, the second messenger in the NO pathway, and hence enhance erections under conditions of sexual stimulation.

- Other options are intracavernosal injection of prostaglandin E (alprostadil), transurethral alprostadil, vacuum therapy and surgical insertion of penile prostheses.

- In women with diabetes, sexual dysfunction is less common and usually undeclared, but there is an increased risk of vaginal dryness and arousal disorder.

- Contraception and family planning are especially important in women with diabetes. Although there is little consensus amongst diabetes professionals about the preferred method of contraception for women with diabetes, it appears that most currently available methods of contraception are suitable.

- Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) can be considered for treating menopausal symptoms in women with diabetes on a short-term basis, but HRT is not justified in asymptomatic women.

Male erectile dysfunction

The advent of effective oral treatments has changed the management of erectile dysfunction (ED) in diabetes considerably. Diabetologists and general practitioners can now offer treatments that are easy to use and generally effective. This change, however, has been a long time coming. As recently as 1993, ED was regarded as the most neglected complication of diabetes [1]. Since then, there has been a transformation in attitudes to the subject, in which diabetes professionals have led the way. Previously, ED was generally believed to be psychogenic in origin, even when associated with diabetes, and hence the management was considered to be the preserve of psychosexual counselors. We now accept that ED is a complications of diabetes that can and should be managed by diabetes professionals.

Physiology of erectile function

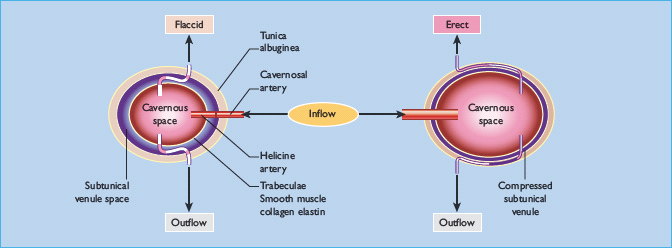

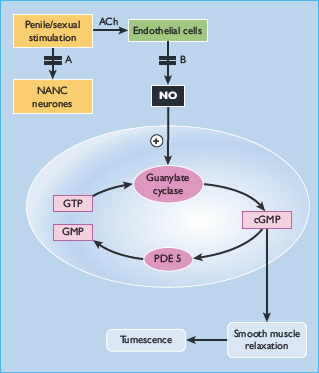

Tumescence is a vascular process under the control of the autonomic nervous system. The erectile tissue of the corpus cavernosum behaves as a sponge, and erection occurs when it becomes engorged with blood. As shown in Figure 45.1, dilatation of the arterioles and vasculature of the corpus cavernosum leads to compression of the outflow venules against the rigid tunica albuginea [2,3]. Thus, smooth muscle relaxation is the key phenomenon in this process, as it leads to increased arterial inflow and reduced venous outflow [4]. The process is under the control of parasympathetic fibres, which were previously known as non-adrenergic non-cholinergic neurones, as the neurotransmitter was unknown; but it is now clear that nitric oxide (NO) is the agent largely responsible for smooth muscle relaxation in the corpus cavernosum. It is produced both in the parasympathetic nerve terminals and is generated by NO synthase in the vascular endothelium. Within the smooth muscle cell of the corpus cavernosum, NO stimulates guanylate cyclase, leading to increased production of the second messenger, cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), which induces smooth muscle relaxation, probably by opening up calcium channels (Figure 45.2) [5,6].

Figure 45.1 Diagrammatic representation of the corpus cavernosum. During tumescence, dilatation of the helicine and cavernosal arteries produces expansion of the cavernosal space and compression of the outfl ow venules against the rigid tunica albuginea.

Figure 45.2 Pathophysiology of erectile function in diabetes. Diagrammatic representation of the pathways leading to the relaxation of a corpus cavernosal smooth muscle cell. In diabetes, there are defects in nitric oxide-mediated smooth-muscle relaxation from neuropathy of the non-adrenergic non-cholinergic (NANC) fibers (a) and endothelial dysfunction (b). ACh, acetylcholine; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; GTP, guanosine triphosphate; NO, nitric oxide; PDE 5, phosphodiesterase type 5.

There is some evidence that neuronally derived NO is important in initiation, whereas NO from the endothelium is responsible for maintenance of the erection [7].

Pathophysiology of erectile dysfunction in diabetes

In men with diabetes there is evidence that ED is caused by failure of NO-induced smooth muscle relaxation caused by both autonomic neuropathy and endothelial dysfunction [7,8]. Many men with diabetes report that in the early stages they do not have a problem initially achieving an erection but that they cannot maintain it. This would suggest that in these individuals failure of endothelium-derived NO occurs before significant autonomic neuropathy.

More recently, other potential abnormalities have been described which may contribute to the development of ED in diabetes. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) has a role in endothelium-dependent relaxation of human penile arteries [9] and this is significantly impaired in penile resistance arteries in men with diabetes [10]. Impaired EDHF responses might therefore contribute to the endothelial dysfunction of diabetic erectile tissue.

A further body of evidence suggests increased oxygen-free radical levels in diabetes may reduce the vasodilator effect of NO. In particular, the formation of products of non-enzymatic glycosylation to produce advanced glycosylation end-products (AGEs) generates reactive oxygen species which impairs NO bioactivity [11]. In animal models, inhibition of AGE formation improves endothelium-dependent relaxation and restores erectile function in diabetic rats [12,13].

Other pathophysiologic changes known to occur in diabetes have been postulated to contribute to ED. Non-enzymatic glycation of proteins has been reported to impair endothelium-dependent relaxation of aorta in rats [13,14].

Other factors, not limited to diabetes, may also contribute to the development of ED in men with diabetes. Structural changes associated with large vessel disease are commonly associated with ED in diabetes; however, this is usually associated with functional changes of widespread endothelial dysfunction in diabetes and it is difficult to separate the relative importance of the two factors.

Other factors contributing to erectile dysfunction in diabetes

In addition to endothelial dysfunction and autonomic neuropathy, ED is associated with other conditions common in diabetes, such as hypertension and large-vessel disease [15]. Furthermore, men with diabetes are more likely to be taking medications that can impair erectile function (Table 45.1). Antihypertensive agents are commonly reported to be associated with ED, although much of the evidence is anecdotal; beta-blockers and thiazide diuretics are the most commonly reported culprits [16]. alpha-blockers perhaps have the lesser risk [17]. Finally, it should be remembered that there are many other potential causes of ED unrelated to diabetes, from which men with diabetes are not immune (Table 45.2).

Table 45.1 Medications associated with erectile dysfunction.

| Antihypertensives Thiazide diuretics Beta-blockers Calcium-channel blockers Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors Central sympatholytics (methyldopa, clonidine) Antidepressants Tricyclics Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (NB: selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors can cause ejaculatory problems) Major tranquillizers Phenothiazines Haloperidol Hormones Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (goserelin, buserelin) Estrogens (diethylstilbestrol/stilbestrol) Anti-androgens (cyproterone) Miscellaneous 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (finasteride) Statins (simvastatin, atorvastatin, pravastatin) Cimetidine Digoxin Metoclopramide Allopurinol Ketoconazole Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents Fibrates Drugs of “abuse” / “social” drugs Alcohol Tobacco Marijuana Amfetamines Anabolic steroids Barbiturates Opiates |

Table 45.2 Conditions associated with erectile dysfunction.

| Psychologic disorders Anxiety about sexual performance Psychologic trauma or abuse Misconceptions Sexual problems in the partner Depression Psychoses Vascular disorders Peripheral vascular disease Hypertension Venous leak Pelvic trauma Neurologic disorders Stroke Multiple sclerosis Spinal and pelvic trauma Peripheral neuropathies Endocrine and metabolic disorders Diabetes Hypogonadism Hyperprolactinemia Hypopituitarism Thyroid dysfunction Hyperlipidemia Renal disease Liver disease Miscellaneous Surgery and trauma Smoking Drug and alcohol abuse Structural abnormalities of the penis |

Clinical aspects of erectile dysfunction in diabetes

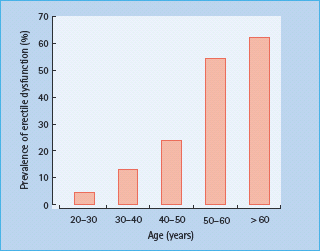

ED becomes more common with age. In a population-based study in Massachusetts, USA, the prevalence of complete erectile failure was reported to be 5% in men in their forties and 15% in those over 70 years [15]. The prevalence in diabetic men is significantly higher and also increases with age. In a survey of men attending a hospital diabetic clinic in the UK, the prevalence of ED increased from 13% amongst 30-year-olds to 61% amongst men aged over 60 years (Figure 45.3) [1]; overall, the prevalence was 38%. The prevalence of ED in diabetes in a general practice population was reported to be even higher, at 55% [18]. These data would suggest that ED is the most common clinically apparent complication of diabetes in men.

Figure 45.3 The prevalence of erectile dysfunction by age of men attending a hospital diabetic clinic [1].

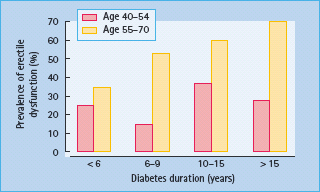

The presence of other medical conditions increases the risk of ED. A population-based survey of 600 men in Brazil, Italy, Japan and Malaysia in 2000 examined the prevalence of ED and its relationship to other diseases and lifestyles. The prevalence of ED among men with diabetes rose from 25% at age 40–44 years to 70% at age 65–70 years [19]. Cardiovascular disease increased the risk of ED. The prevalence was 31.7% in men with diabetes only, 40% in men with diabetes and heart disease and 46.5% in those with diabetes and hypertension. The prevalence also increased with duration of diabetes (Figure 45.4). Men with diabetes who smoked and reported below average levels of physical activity had a fourfold increase in the prevalence of ED.

Figure 45.4 The prevalence of erectile dysfunction by duration of diabetes in a population – based study [19].

Erectile dysfunction as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease

There is convincing evidence of an association of between ED and cardiovascular disease [20–22]. This may be because they share common risk factors. Increased waist measurement and reduced physical activity, both important risk factors for ischemic heart disease, considerably increase the risk of ED [23–25]. The risk of ED is also increased in men with hyperlipidemia [26].

Recent studies have suggested that the association between ED and cardiovascular disease may be brought about by more than shared risk factors and may arise because they are both manifestations of endothelial dysfunction. There has been considerable interest in recent years in the role of the vascular endothelium in the pathogenesis and progression of atherosclerosis [27]. It is clear that the endothelium has important and complex endocrine and paracrine functions, and one of its most important products is NO (previously known as endothelium-derived relaxing factor). NO possesses potent antiatherogenic properties, inhibits platelet aggregation and regulates vascular tone [28]. As described above, NO derived from both nerve terminals and the vascular endothelium has a central role in the physiology of erection. Therefore, there are theoretical grounds to believe that the ED might be an early marker of endothelial dysfunction and hence an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease. There is now good evidence that ED is an early marker of endothelial dysfunction [29]. Thus, the association between ED and increased cardiovascular risk may be a case of shared common soil, in particular endothelial dysfunction and microvascular disease. In practical terms this means cardiovascular risk should be assessed in any man with ED whether diabetic or not. A man with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and ED has approximately double the risk of developing coronary heart disease than a similar man without ED [22].

Smoking and alcohol consumption

Smoking greatly increases the risk of developing ED. A follow-up of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study reported that cigarette smoking almost doubled the risk of developing ED after about 7 years [15]. A similar finding was reported by the large Health Professionals’ Follow-up Study [24].

In contrast to tobacco, it is well established that moderate alcohol consumption reduces the risk of a cardiovascular event. It is interesting that drinking alcohol in moderation also appears to reduce the risk of becoming impotent [23].

Quality of life issues

That ED can significantly worsen a man’s quality of life is not in doubt. Unfortunately, there are few good data to show objectively the impact ED can have on quality of life measures, and even fewer to show the impact of treating ED. A survey by the Impotence Association found symptoms of lowered self-esteem and depression in 62% of men; 40% expressed concern with either new or established relationships, and 21% blamed it for the break-up of a relationship [30]. In another series in general practice, it was reported that 45% of men with diabetes stated that they thought about their ED all or most of the time, 23% felt that it severely affected their quality of life and 10% felt it severely affected their relationship with their partner [18].

Assessment and investigation of erectile dysfunction in diabetes

Clinical assessment

In most cases, an impotent man will have taken a long time to pluck up the courage to discuss his problem with a doctor and will undoubtedly be anxious. Almost invariably, however, once the subject has been broached, men with ED and their partners do not usually have any difficulty discussing the problem. A description of the nature of the ED should be obtained, not least to ensure that the patient is complaining of ED and not another related problem, such as premature ejaculation. The key features in the history of ED are listed in Table 45.3. Ideally, the man’ s partner should be present, but most men attend the consultation alone. If the partner is present, talking to her without the patient present can reveal interesting and useful insights into the problem.

Table 45.3 Key features in the clinical history of erectile dysfunction in diabetes.

| Onset usually gradual and progressive Earliest feature often inability to sustain erection long enough for satisfactory intercourse Erectile failure may be intermittent initially Sudden onset often thought to indicate a psychogenic cause (but little evidence to support this) Preservation of spontaneous and early morning erections does not necessarily indicate a psychogenic cause Loss of libido consistent with hypogonadism, but not a reliable symptom. Impotent men often understate their sex drive for a variety of reasons |

General physical examination may give clues as to the etiology of ED and the choice of treatment. The key features of the physical examination are listed in Table 45.4.

Table 45.4 Key physical signs to note on examination of the patient with erectile dysfunction.

| Any features of hypogonadism Manual dexterity – may preclude physical treatment (e.g. intracavernosal injection) Protuberant abdomen External genitalia: Presence of phimosis Testicular volume |

Investigation of erectile dysfunction in diabetes

The suggested investigations of ED in diabetes are listed in Table 45.5. It is now widely accepted that it is not helpful to try to determine whether or not ED is psychogenic in origin, particularly when managing a man with diabetes and ED. Few investigations are needed, but it is worth excluding other treatable causes of ED: in practical terms, hypogonadism is the only treatable one. There is probably no significant relationship between diabetes and hypogonadism, and therefore gonadal function should only be assessed in men with diabetes and ED if it is considered worthwhile looking for a coincidental problem causing hypogonadism. Some men presenting with ED will not have attended any form of clinic for many years, so the consultation provides an opportunity to address other health issues. For the reasons given above, consideration should be given to assessing the patient’ s cardiovascular status. The consultation also provides an opportunity to address the management of the patient’s diabetes.

Table 45.5 Investigation of erectile dysfunction in diabetes.

| Serum testosterone if libido reduced or hypogonadism suspected (ideally taken at 9 am) Serum prolactin and luteinizing hormone if serum testosterone subnormal Assessment of cardiovascular status if clinically indicated: Electrocardiography (ECG) Serum lipids Glycosylated hemoglobin, serum electrolytes if clinically indicated |

General advice

Most men with diabetes and their partners seeking treatment for impotence are middle-aged, have been married for many years and require only simple common-sense advice. Specialist psychosexual counseling is not needed for most couples: several series have reported that diabetologists can offer an effective service for the treatment of ED without the support of psychosexual counselors [31–34]. It is important that the cause of the ED is explained as many patients will blame themselves. They should be advised that if they wish to resume sexual relations they will require long-term treatment, as spontaneous return of erectile function in diabetes occurs only rarely [35].

Treating ED in an attempt to save a failing relationship is rarely successful and may make the situation worse. The assistance of a suitably qualified psychosexual counselor should be considered in this situation. Referral to a counselor should also be considered if there is any suggestion of severe anxiety, loss of attraction between partners, fear of intimacy or marked performance anxiety. Any other medical problems should be addressed. Improving poor metabolic control may help general well-being but poor control should not be used as a reason to refuse or delay treatment. Patients who smoke should be advised to stop for reasons of general health, although there is no good evidence that stopping smoking will improve erectile function in a man with diabetes and ED.

Many men with diabetes will be taking medication known to cause ED. Experience has shown that changing the treatment in an attempt to improve sexual function rarely works and may cause delays and frustration for the patient. It is therefore not advisable unless there is a strong temporal relationship between starting treatment and the onset of ED.

Treatment options

The advent of effective oral therapies has transformed the management of ED. These should be offered as first-line therapy to men with diabetes and ED, and the other treatment options should be reserved for those in whom oral therapy is contraindicated or ineffective.

Oral agents

Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors

Phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE 5) is an enzyme found in smooth muscle, platelets and the corpus cavernosum. The mechanism of action of PDE 5 inhibitors is shown in Figure 45.2. During tumescence, there is an increase in the intracellular concentrations of NO, which produces smooth muscle relaxation via the second messenger cGMP. This is broken down in turn by PDE 5. Hence, PDE 5 inhibitors can enhance erections under conditions of sexual stimulation. There are currently three PDE 5 inhibitors licensed for the treatment of ED: sildenafil (Viagra), tadalafil (Cialis) and vardenafil (Levitra).

Clinical trial data. Sildenafil was the first PDE 5 inhibitor. Early small trials showed it was a highly effective treatment for ED in men with and without diabetes [36,37]. The first large study was published in 1998. A total of 532 men with ED of mixed etiology were studied. In the group given sildenafil, 69% of all attempts at intercourse were successful, compared with 22% in those given placebo [38]. Other studies in men with ED of mixed etiology have shown success rates of 65–77% [39,40]. Studies of sildenafil in other patient groups have reported success rates of approximately 70% in hypertension [41], 76% in spinal cord injury [42], 63% in spina bifida [43] and 40% following radical prostatectomy [44].

In men with diabetes, the success rates for sildenafil have been reported to be 56–59% in the treatment of ED [37,45]. A study in elderly men reported success rates of 69% overall and 50% in subjects with diabetes [46]. Most of these studies of sildenafil have been short-term. A trial examining the long-term efficacy of sildenafil in men with ED from a variety of causes reported that only 52% continued to use it after 2 years [47]. This figure may seem surprisingly low, but it is certainly considerably higher than for any other type of ED treatment.

Other PDE 5 inhibitors

Sildenafil was soon followed by tadalafil (Cialis) [48–50] and vardenafil (Levitra) [51,52]. All three appear to be similar in efficacy and safety but there are differences in duration of action and adverse effect profiles as described below.

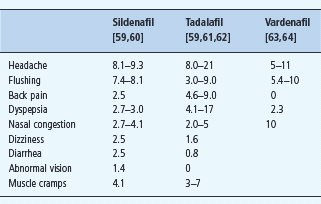

Adverse effects. The most common adverse effects related to PDE 5 inhibitors are headache, dyspepsia and flushing. Headache and flushing might be expected, as they are vasodilators. The dyspepsia is usually mild and may be caused by relaxation of the cardiac sphincter of the stomach.

Abnormal vision is experienced by about 6% of men taking sildenafil; this may be because the drug has some activity against PDE 6, which is a retinal enzyme. Of more concern are the reports of non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION). This is a rare syndrome characterized by sudden, sometimes unilateral, often reversible, visual loss. Since 2002 there have been case reports of this condition occurring in association with the use of PDE 5 inhibitors, particularly sildenafil [53,54]. NAION is rare but potentially serious as it can, exceptionally, lead to blindness. It would appear it is more common in men with increased cardiovascular risk [55]. The manufacturers of sildenafil estimated the incidence of NAION in 13 000 men receiving sildenafil from pooled safety data from clinical trials and observational studies to be 2.8 cases per 100 000 patient-years of sildenafil exposure [56]. The authors reported this to be similar to estimates reported in general US population samples (2.52 and 11.8 cases per 100 000 men aged over 50 years). It is therefore unknown if PDE 5 inhibitor use increases the risk of NAION but in any case it is a very rare condition and should not discourage the appropriate use of these agents.

The adverse events from the key trials of PDE 5 inhibitors in men with diabetes are given in Table 45.6. In all the studies, the discontinuation rate from adverse effects has been very low.

Table 45.6 Adverse effects of phosphodiesterase 5 ( PDE 5) inhibitors (%). The prevalence quoted for each adverse effect is for the top dose used in each study.

Reasons for PDE 5 inhibitor non-responsiveness. The mechanism of action of sildenafil would suggest that it would be ineffective without the presence of sufficient bioavailable NO in the penile vasculature. Thus, either significant autonomic neuropathy or endothelial dysfunction would be expected to reduce the efficacy of a PDE 5 inhibitor. Slightly surprisingly, two small studies have reported no differences in the presence of autonomic or endothelial function between sildenafil “responders” and “non-responders” [29,57]. It has been reported that failure to respond to sildenafil is more likely in men with long-standing and severe ED [58]; however, no single factor precludes a successful outcome, and in practical terms it is worth trying sildenafil in all men with ED unless there is a contraindication.

Cardiovascular safety of PDE 5 inhibitors. The launch of sildenafil, the first PDE 5 inhibitor, was soon followed by case reports of cardiovascular events and deaths associated with its use. By contrast, there is now good evidence that PDE 5 inhibitors are not associated with increased cardiovascular risk [65,66]. A questionnaire survey of over 5000 sildenafil users reported that adverse cardiovascular events were no more frequent than expected for a comparable population [67]. A retrospective analysis of 36 clinical trials of tadalafil involving over 14 000 men reported no increase in cardiovascular adverse events [68]. Indeed, there is accumulating evidence that PDE 5 inhibitors reduce blood pressure slightly and improve endothelial function [66,69].

Restoring sexual function, however, is not completely without risk. Sexual activity, like any form of physical activity, can precipitate cardiovascular events in those at risk. A large case–control study reported the risk of a cardiovascular event in the 2 hours after intercourse was increased by 2.5 fold in healthy subjects and by 3 fold if there was a history of previous myocardial infarction [70]. Although the absolute risk remains very small, the issue of cardiovascular safety must be addressed in all men before treating ED. Jackson et al. [65] have suggested a classification scheme for assessing cardiovascular risk in men undergoing treatment for ED, those with the highest risk should be referred for specialist cardiac evaluation while the lowest risk group could be managed in primary care.

Drug interactions with PDE 5 inhibitors. PDE 5 inhibitors can be used safely in patients taking a wide range of other drugs but there are several potential important interactions. They are contraindicated in the presence of any nitrate therapy (including nicorandil) as the combination can cause profound hypotension. A patient taking nitrates seeking treatment for ED can be offered alternatives to PDE 5 inhibitors or the nitrates can be stopped or changed to an alternative therapy. Nitrates are a symptomatic treatment with no prognostic implications and so this is possible in most cases but should be done in consultation with a cardiologist in all but the most straightforward cases.

Nitrate therapy should not be given within 24 hours of taking sildenafil or vardenafil and at least 48 hours of taking tadalafil. If angina develops during or after sexual activity following the use of a PDE 5 inhibitor, the patient should be advised to discontinue any sexual activity and stand up as this reduces the work of the heart by reducing venous return.

PDE 5 inhibitors should be used with caution in patients who take alpha-blockers because the combination may lead to symptomatic hypotension in some patients. Patients should be stable on alpha-blocker therapy before initiating sildenafil which should be initiated at the lowest dose [66].

Comparison of PDE 5 inhibitors. The three currently available PDE 5 inhibitors, sildenafil, vardenafil and tadalafil, are all similar in efficacy and safety. Their side effect profiles differ slightly but the most notable difference is the longer half-life of tadalafil. Thus, a single dose of tadalafil offers the potential to restore erectile function to normal for 2 days and thereby remove the need for medication to be taken each time prior to sexual activity. The choice between this form of treatment and on-demand dosing is largely a matter of patient choice. Patient preference studies of agents with differing dosing instructions are difficult to perform in a blinded fashion. Several have been reported and have generally shown a preference for tadalafil over sildenafil [59,71–74].

How to use PDE 5 inhibitors. These agents should be taken orally about 1 hour before sexual activity. This period can be shortened if taken on an empty stomach. After the 1-hour period, there is a “window of opportunity” when sexual activity can take place. For sildenafil and vardenafil this is at least 4 hours but may be over 8 hours [75]. For tadalafil the window of opportunity may last 48 hours. Men with diabetes usually require the maximum recommended dose. Patients should be warned that the drug only works in conjunction with sexual stimulation.

Management of PDE 5 inhibitor non-responsiveness. A large proportion of men with diabetes and ED will not respond to PDE 5 inhibitors and there are many potential reasons for this. PDE 5 inhibitors require a degree of NO tone to be effective, therefore severe endothelial dysfunction of autonomic neuropathy might be expected to reduce their efficacy; however, one study reported that neither autonomic neuropathy nor endothelial dysfunction predicted sildenafil responsiveness. The only significant factor that predicted the response to treatment was the initial degree of ED [29]. In practical terms, no single factor should preclude a trial of PDE 5 inhibitor therapy in a man without a contraindication.

Much has been written on the best approach for dealing with men who do not respond to a PDE 5 inhibitor but, unfortunately, mostly based on limited evidence. It has been suggested that if appropriate advice is given and sufficient attempts at intercourse made, many men previously labeled as non-responders can be treated successfully with PDE 5 inhibitors. One study reported that intercourse success rates reached a plateau after eight attempts so men with ED should try at least eight times with a PDE5 inhibitor at the maximum recommended dose before being considered a non-responder [76].

Hypogonadism should always be considered in dealing with men with ED who do not respond. Hypogonadism caused by confirmed pituitary or testicular disease usually responds well to treatment. The management of the borderline hypogonadism of the aging male is more controversial but there is some evidence that testosterone replacement in this situation can improve ED as a sole treatment [77] and enhance the response to PDE 5 inhibitors [78–80].

Other oral therapies

Apomorphine

Apomorphine has been in use for many years. It is a centrally acting D1/D2 dopamine agonist that acts on the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus early in the cascade that leads to erection. Among its several properties, it is a potent inducer of nausea, and this has previously limited its use as a therapeutic agent. A sublingual formulation is licensed in Europe as a treatment of ED. This preparation has no first-pass metabolism, and it rapidly produces therapeutic blood levels. Studies of the sublingual preparation have suggested that it is effective in inducing erections in about 50% of attempts and has acceptable levels of adverse effects [81]. To date, there have been no published trials of apomorphine in men with diabetes and it is not widely used in diabetic practice.

Various oral agents have been tried as treatments for ED in the past, including trazodone, yohimbine and phentolamine. The data on all of them are limited and none has stood the test of time. Testosterone should only be used to treat ED secondary to confirmed hypogonadism.

Intracavernosal injection therapy

The technique of intracavernosal self-injection was first described in 1982 by Brindley [82], using phentolamine, although the French urologist, Virag [83]. who used papaverine, was first to publish. Papaverine was more effective than phentolamine, but was an unlicensed treatment; it was superseded by alprostadil (prostaglandin E), which was licensed for the treatment of ED in 1996.

Alprostadil is supplied in a self-injection pen device, which is easy to use, and supplied with excellent instructions (Figure 45.5). In spite of this, most studies show that self-injection therapy has a disappointingly high long-term discontinuation rate [84–86]. Self-injection treatment carries a small risk of priapism (a sustained unwanted erection). Although an infrequent complication, priapism is an important one, as it must be treated within 6 hours by aspirating blood from the corpus cavernosum. Patients undertaking self-injection must be warned of this potential problem and given instructions on what to do should it occur (Table 45.7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree