- Peripheral arterial disease is very common, affecting up to 30% of all people with diabetes.

- Amputations are much more common in patients with diabetes and occur 5–8 times more often than in those without the disease.

- Atherosclerosis is common in people with diabetes, and measurement of ankle blood pressure may identify both people with and without diabetes at an early asymptomatic stage.

- People with diabetes have atherosclerotic lesions located more peripherally than people without diabetes and therefore are more commonly inoperable for technical reasons.

- People with diabetes have more complications to surgery, both locally (infections) and systemically (e.g. cardiac, pulmonary) than people without diabetes.

- Treatment of atherosclerosis in diabetes is basically the same as in patients without diabetes.

Introduction

Peripheral vascular disease includes diseases to arteries and veins outside the thoracic region. Because of the limitations of a chapter in a textbook dealing with diabetes, this chapter mainly covers the three most common arterial diseases: peripheral arterial disease (PAD), carotid artery disease and aortic aneurysmatic disease (AAA). Other, rarer manifestations of atherosclerotic disease (e.g. renovascular hypertension, abdominal angina and ischemia of the upper extremity) are mentioned briefly. Special considerations in patients with diabetes are dealt with in relevant sections; for example, infection in an ischemic foot in a patient with diabetes is described in the section on critical limb ischemia.

Atherosclerosis is the main cause of peripheral arterial vascular disease, and the overall pathogenesis is covered in Chapter 39. It is important to appreciate that the pathogenetic mechanisms of clinical atherosclerosis are dual: chronic obstructive and thrombotic. Whereas the chronic obstructive mechanism is the main cause of lower limb ischemia, also in patients with diabetes, it is often preceeded by a thrombotic event; a patient with mild claudication suddenly experiences significantly shortening of walking distance or sudden onset of rest pain. Or, the seemingly healthy person suddenly develops claudication. Of course, a heart attack or stroke in a patient with claudication is also a thrombotic event in a patient with chronic obstructive disease.

In general, patients with diabetes more often develop symptoms of atherosclerotic complications, they do it at a younger age and they are more difficult to treat and have more complications with treatment (especially with invasive treatment).

Peripheral arterial disease

Peripheral arterial disease is a chronic condition that, like atherosclerosis in other vascular beds, develops over decades. The World Health Organization (WHO) definition includes exercise-related pain and/or ankle brachial index (ABI) <0.9. On average, symptoms from the lower limbs develop 5–10 years later than from the coronary circulation. Acute ischemia may develop because of:

Diabetes is a major contributor to PAD.

PAD is traditionally divided into four stages (Fontaine):

Incidence

In the most recent population-based studies in Western Europe, the incidence of symptomatic PAD is 3–4% among 60- to 65-year-olds, increasing to 15–20% in persons 85–90 years of age [1–3]. Similar findings have been reported in the USA. Looking at asymptomatic cases where the ABI is <0.9, the incidence is much higher, and approximately 20% of all persons above 65 years of age, ranging from 10% in persons 60–65 years of age to almost 50% of those aged 85–90 years [1–3]. Critical limb ischemia, defined as ABI <0.4 or rest pain and/or non-healing ulcers, occurs in 1% of persons aged 65 years or older.

Incidence of PAD in people with diabetes

The incidence of PAD in people with diabetes depends on the usual atherosclerosis risk factors and duration of diabetes. There are only few demographic studies studying the general population. Using ABI <0.9 as selection criteria, Lange et al. [4] found a prevalence of 26.3% in people with diabetes compared to 15.3% in people without diabetes when screening 6880 Germans above 65 years of age, of whom 1743 had diabetes. Similar findings have been reported by others: 20–30% of those with diabetes have PAD [5,6]. Claudication is twice as common in those with diabetes than those who do not have diabetes.

Pathophysiology

It is outside the scope of this chapter to describe the pathophysiology of PAD in detail (see Chapter 39); however, in brief, the pathophysiology of PAD in those with diabetes is similar to that of a non-diabetic population. The abnormal metabolic state that accompanies diabetes directly contributes to the development of atherosclerosis. Pro-atherogenic changes include increases in vascular inflammation and alterations in multiple cell types. Both mechanisms of atherosclerotic complications are of importance in PAD (gradual narrowing resulting in stenosis and acute thrombosis in existing atherosclerotic lesion). Obviously, the long-term accumulation of lipids in the vessel wall is important and sudden local thrombosis can occur at any time, although in most cases this happens after symptoms (claudication) have developed.

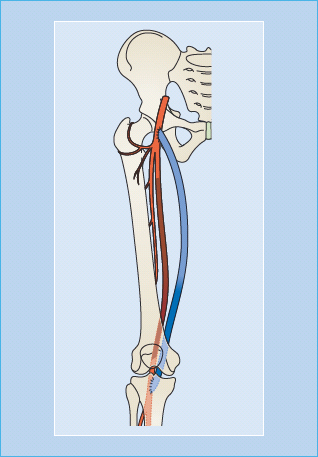

To reach the stage of critical limb-threatening ischemia, advanced atherosclerosis has developed. Often, multiple segments of the arterial tree from the aorta to the foot are affected (stenotic and/or occluded). In people with diabetes, the atherosclerotic lesions are more peripherally located than in people without diabetes. Whereas the iliac and femoral arteries are most commonly stenotic and/or occluded in individuals without diabetes, in those with diabetes, it is most often the crural arteries that are severely affected by atherosclerosis. This poses a challenge for revascularization because the results in general are better the more proximal the reconstruction.

In order to develop ischemic non-healing ulcers, perfusion has to be very poor. The most reliable method for assessment of peripheral perfusion in those with diabetes is measurement of toe pressure. A toe pressure below 20–25 mmHg signals a poor chance of healing of a peripherally located ulcer. The special considerations related to the potentially dramatic course of infection in a diabetic foot are dealt with in Chapter 44.

Asymptomatic stage

The asymptomatic stage of PAD is especially interesting because it is associated with an approximately threefold increased mortality compared to matched controls [7,8]. This excess mortality is caused by accompanying cardiovascular disease (CVD). Asymptomatic PAD can be identified by a very simple test: measurement of ankle blood pressure. This test takes only a few minutes and is expressed as the ABI, where the ankle pressure is divided by the highest of the two arm blood pressures (BPs). In this manner, variations in BP between measurements do not influence the test result. Not only is an ABI <0.9 associated with increased mortality from cardiovascular causes, but also the level of ABI reduction is predictive: the lower the ABI the worse prognosis [7].

Identifying an asymptomatic person with an ABI <0.9 is not a case for evaluation with respect to revascularization of the lower limbs, but a case for serious preventive cardiovascular medicine.

Claudication

Claudication is experienced by the patient as pain in lower limb muscles appearing after walking, most often in the calf, the thigh and more rarely in the buttocks. The walking distance eliciting the pain is very variable, beginning after 10–15 meters in severe cases, whereas other patients will report pain only when walking fast uphill for more than 500 meters for example. It is important for both the patient and the treating physician to understand that claudication, although it may be incapacitating for a few, and troublesome for many, signals severe vascular disease systemically, and that cardiovascular morbidity and mortality is high (elevated 3–4 times compared to matched controls).

Rest pain

Rest pain typically begins at night when the patient is in the horizontal position. The positive effect of gravity on lower limb perfusion is then abolished. The patient typically complains about pain in the toes or feet during the night and most have experienced that standing or sitting up relieves the pain. Many patients will sleep sitting in a chair.

In patients with diabetes, symptomatology may differ because of coincidal peripheral neuropathy. Just like myocardial ischemia can be masked, symptoms from the lower extremity may be missing even though peripheral ischemia exists. This is especially important when a patient with diabetes presents with a small ulcer or wound on the lower limb, even if the patient thinks there is a good explanation for developing the ulcer, such as a relevant trauma. The lack of symptoms to signal peripheral ischemia combined with the risk of escalating infection in a diabetic foot has prompted many diabetologists to recommend routine assessment of peripheral circulation at regular intervals in all people with diabetes.

Non-healing ulcers

Non-healing ulcers often begin after minor trauma (e.g. hitting a toe against a chair or by using shoes that are too small). In some cases the ulcers develop without any trauma and those will often progress to gangrene if not treated. Ischemic ulcers develop on toes or on the foot, typically at points where shoes are in firm contact. Thus, they are usually easy to discriminate from venous ulcers, which are located at the level of the ankles or lower calf.

Rest pain, non-healing ulcers and/or gangrene are often referred to as critical ischemia. The “diabetic foot” is dealt with in Chapter 44.

Diagnosis

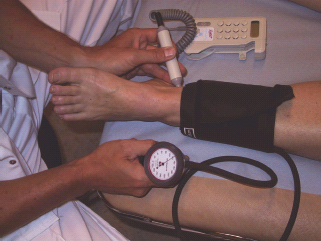

Most often the history and objective findings will ensure the diagnosis, but measurement of ankle blood pressure will quantify the ischemia and can be used to monitor changes in the disease (Figure 43.1). In some patients with diabetes, the media of smaller arteries become calcified making them incompressible. Thus, very high ankle pressures resulting in elevated ABI (>1.3) signals mediasclerosis and should be recognized as a falsely elevated measurement. In fact, ABI >1.3 is associated with a marked increased mortality because media sclerosis is found in patients with diabetes and those with renal failure.

Because small arteries are rarely affected by media sclerosis, measurement of toe pressure is an alternative for assessment of PAD. Use of the strain gauge technique is most commonly used (Figure 43.2). Toe pressure also is useful for prediction of healing of ulcers and amputation wounds.

Prognosis

The risk of amputation is only 1–2% at 5 years. Twenty-five percent of patients with claudication will experience a worsening of their symptoms from the lower legs; however, 75% will be unchanged or improve without revascularization [9]. In contrast the “systemic” risk is huge. Mortality in 5 years will be 15–25% and many more will have non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke.

The risk of a patient with diabetes and PAD is much higher than that of the average patient with PAD. The patient with diabetes has an 8 times greater risk of amputation at the level of the transmetatarsal bones or above than the non-diabetic population [10]. In addition to the already severely increased mortality of PAD, patients who additionally have diabetes have a further doubling of their risk of death [10–12].

Treatment

Treatment of patients with symptoms from the lower limb therefore involves two aspects:

- Treatment of symptoms from the lower limb; and

- Prevention of cardiovascular complications

The former includes lifestyle modification, medical therapy and interventional therapy by either percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) or open surgery, whereas the latter includes lifestyle modification and preventive medical therapy.

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to detail all aspects of lifestyle modification and preventive medical therapy; however, it is extremely important for the reader to understand that patients with PAD derive as much or greater benefit from lifestyle modification and aggressive preventive medical therapy than any other group of patients (see Chapter 40). Most of the lifestyle changes which are beneficial to the patient with diabetes will benefit the PAD aspect as well, especially smoking cessation, regular exercise, weight loss and dietary changes.

Medical prevention follows the same guidelines as that of other clinical atherosclerotic manifestations such as ischemic heart disease and can be summarized as follows: aggressive statin treatment almost irrespective of cholesterol levels (Heart Protection Study and American Heart Association guidelines), antiplatetet therapy and BP control. In this chapter, only details of lifestyle modification and medical therapy relevant to PTA and surgery are discussed.

Treatment of symptoms from the lower limb

The vast majority of patients should be managed without invasive intervention PTA (and/or surgery). Because the risk of cardiovascular complications (cardiac and cerebral) is much higher than the risk of amputation, the main focus should be on preventive measures in order to halt the atherosclerotic process. The conservative approach with respect to revascularization is especially important for patients with diabetes because of the increased risk of surgical complications and poorer results of revascularization. One exception is patients with critical limb ischemia. Early revascularization before widespread infection can be limb-saving.

Exercise therapy has proven effective for improvement of walking distance, and regular exercise for 3 months can be expected to improve walking distance by 200–250% [13]. Because exercise also reduces cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, it cannot be stressed enough (for both the patient and the physician) that this is extremely important. Because the effect on walking distance is so good, and because it is important for survival, exercise therapy should always be tried before considering interventional treatment. There are only few exceptions where interventional treatment may be considered early on:

The dilemma of explaining to patients that the symptoms they are experiencing from the lower limb are signaling high cardiovascular risk rather than lower limb risk is challenging. First of all, there is (or has been) a general perception that atherosclerosis in the limb is less dangerous than in other locations. The author hopes that the introductory remarks in this chapter have changed this potential misperception for the reader. Medical therapy for claudication includes cilostazol and statins. Treatment with both may be expected to improve walking distance by 30–50% and the latter furthermore reduces the cardiovascular risk. Other drugs have not proven useful in improving walking distance significantly [14].

Interventional treatment

Interventional treatment (endovascular or open surgery) for PAD is indicated when:

- Exercise and other lifestyle modification has failed to improve symptoms to an acceptable state;

- Claudication is incapacitating; or

- Critical limb ischemia is present (rest pain, non-healing ulcers and/or gangrene).

Again, for the patient with diabetes, the indication for revas-cularization should be considered very carefully in patients only with claudication. The choice between PTA and open surgical management depends on the location and extent of disease. In general, endovascular treatment can be expected to perform well in cases of shorter lesions whereas open surgery is preferred in cases of extensive occlusive disease. Obviously, whenever comparable results can be obtained, PTA is preferred for the simple reason that it is less invasive and associated with less complications than open arterial reconstructions. In patients with severe co-morbidity that might complicate the outcome of open surgery, PTA would be preferred even though theoretically surgery would be the treatment of choice if only patency of the revascularization procedure was considered.

The arterial lesions causing obstruction of blood supply to the lower limb are most often located in the distal abdominal aorta just proximally to the aorta–iliac bifurcation, in the iliac arteries, and in the common and superficial femoral arteries. The arteries in the calf, the anterior and posterior tibial and the peroneal artery, are often involved in those with critical ischemia and with diabetes. In general, when patients with diabetes present with symptoms, they have a more distal involvement with open vessels to the level of the popliteal artery and then occlusive disease of the calf vessels and sometimes also the arteries in the foot. The results of revascularization for patients with diabetes with toe or foot ulcers are worse than the general population partly because reconstructions yield better results with respect to patency when the lesions are more centrally located.

Percutaneus transluminal angioplasty

In principle, PTA can be performed anywhere between the heart and the feet. The more centrally located the lesions being treated, the better the results, especially with PTA. Also, the shorter the stenosis or occlusion, the better the results, and stenting improves patency in most cases. Endovascular-treated common iliac arteries, as an example, remain patent in 60–80% of cases after 5 years and thereafter they may be redilatated. Primary stenting has become the preferred treatment in most cases. Obviously, because complications are rare, and this procedure is associated with the best results, the tendency to offer PTA for iliac artery obstruction is greater than for occlusive disease more peripherally located.

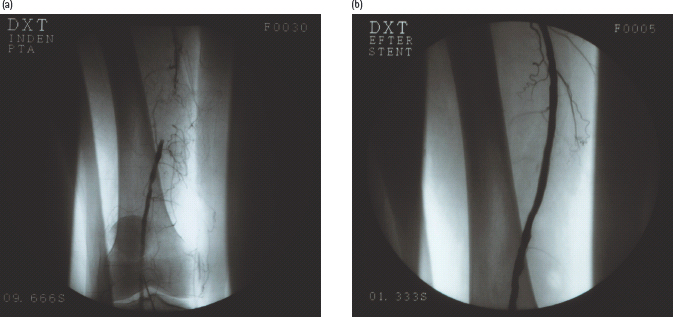

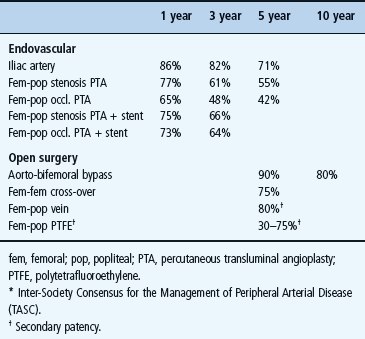

PTA of the superficial femoral artery (Figure 43.3) may relieve symptoms, but the results depend on the extent of disease. The longer the lesion, the greater the risk of early reocclusion. Stenting appears to improve patency, at least for longer lesions (Table 43.1) [15]. When the indication for PTA is claudication, patency is better than if the indication is critical ischemia. This difference relates to the more extensive nature of the disease in the case of critical limb ischemia and may also relate to poor run-off vessels. The 3-year patency is 48%, which may be improved to 64% if stenting is added. In case of critical limb ischemia, the results at 3 years show a patency of 30% without stenting and 63% with stenting (Table 43.1) [15]. PTA of crural vessels is also feasible; however, the long-term results are not good. Data on limb salvage with PTA of crural vessels alone are scarce. Adjunctive medical therapy to improve patency following PTA and stenting, with anticoagulation and/or antiplatelet therapy, has been tested only in a few trials. Antiplatelet drugs improve patency, and the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel may be beneficial [16].

Figure 43.3 Short occlusion of the superficial femoral artery (a) treated with PTA and stenting (b).

Table 43.1 Pooled patency of vascular reconstructions (TASC*II).

Open surgical revascularization

Open surgical revascularization still dominates as the treatment of choice in cases of critical limb ischemia, because of the extensive nature of the atherosclerotic lesions in these patients. For claudication, open surgical treatment is rarely performed, while for extensive disease of the distal aorta and iliac arteries, the aorto-bifemoral bypass remains the procedure with the best long-term outcome. In addition, femoral-femoral cross-over bypass may be performed for unilateral iliac artery occlusion. Also, endarterectomy, as described below, may be an option for treatment of claudication. Only one trial has compared open surgery with endovascular treatment of critical limb ischemia, the Bypass versus Angioplasty in Severe Ischaemia of the Leg (BASIL) trial [17]. The primary efficacy outcome measure was amputation-free survival, but because approximately two-thirds of the endpoints were deaths, only one-third of the endpoints really determined which procedure was best. Within 6 months post-operatively, there was no difference in the primary endpoint, but thereafter bypass patients seemed to do better [17].

In general, two surgical techniques are used: endarterectomy and bypass. Endarterectomy is performed by separating the intima from the media, and in this manner the atherosclerotic lesion can be removed. Endarterectomy can be used in cases with severe occlusive lesions of limited anatomic extension, in the external iliac or in the common femoral artery. The advantage of this technique is that it can often be performed without the use of artificial graft material and patency is excellent. Bypass is preferred when the obstructive and/or occlusive lesions are extensive (e.g. total superficial femoral artery occlusion or multiple serial lesions warranting a femoral–crural bypass) (Figure 43.4). Bypass surgery can be performed with artificial materials or with autologous veins. For bypass of aortic or iliac artery origin, artificial grafts are almost always used. This is because there is no easily removable vein with similar dimensions that can be used in these locations. Also, Dacron or polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) grafts perform very well in the aorto-iliac–femoral region. For peripheral bypasses, typically originating from the common femoral artery, autologous vein grafts are preferred for two reasons: they last longer (much better patency) (Table 43.1) and they carry less risk of infection. For longer bypasses, such as from the common femoral to the popliteal artery below the knee, a saphenous bypass is performed leaving the vein in situ. This means that the vein is left in its original anatomic location; however, the proximal and distal ends are anatomized to the arterial system. The venous valves are cut with a knife mounted on a catheter and side branches are occluded. In this manner, the vein retains its nervous innervations and native vascularization.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree