- Pancreatic disease is a rare cause of diabetes.

- Acute pancreatitis is associated with transient hyperglycemia which rarely persists.

- Chronic pancreatitis secondary to any cause can lead to permanent diabetes which is typically difficult to control; imaging studies reveal dilated ducts and pancreatic calculi.

- Tropical calcific pancreatitis is a disease of unknown etiology found in low and middle income countries associated with large pancreatic calculi and diabetes (fibrocalculous pancreatic diabetes).

- Hereditary hemochromatosis is an inherited disorder that produces diabetes secondary to iron deposition in the pancreatic islets and subsequent islet cell damage.

- Pancreatic carcinoma may complicate type 2 diabetes, diabetes secondary to chronic pancreatitis and, most commonly, with fibrocalculous pancreatic diabetes. It is important to suspect malignancy in any patient who complains of back pain, jaundice or weight loss in spite of good glycemic control.

- Pancreatic surgery can lead to diabetes that is insulin-requiring and often difficult to control.

- Cystic fibrosis is a relatively common genetic disorder affecting the lung, pancreas and other organs. Up to 75% of adults with cystic fibrosis have some degree of glucose intolerance.

Introduction

Pancreatic disease is a rare cause of diabetes, accounting for less than 0.5% of all cases of diabetes. A number of disease processes affecting the pancreas can lead to diabetes; some of these are listed in Table 18.1.

Table 18.1 Pancreatic diseases associated with glucose intolerance and diabetes.

| Inflammatory |

| Acute |

| Chronic, including fibrocalculous pancreatic diabetes |

| Infiltration |

| Hereditary hemochromatosis |

| Secondary hemochromatosis |

| Very rare causes: sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, cystinosis |

| Neoplasia |

| Adenocarcinoma of the pancreas |

| Glucagonoma |

| Surgical resection or trauma |

| Cystic fibrosis |

Most of these conditions damage the exocrine as well as endocrine components of the pancreas. The exocrine parenchyma and islet tissue lie in intimate contact with each other and are functionally related. This may explain why parenchymal disease can readily impair β-cell function [1].

Acute pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis varies considerably in its impact on the gland and its metabolism. Pathologic findings vary from mild edema to hemorrhagic necrosis, and the clinical presentation spans a wide spectrum from mild to fulminating or fatal illness.

The most common causes of acute pancreatitis are alcoholism and gallstone disease. Table 18.2 sets out the causes of acute pancreatitis. Classically, the disease presents with sudden onset of epigastric pain, associated with nausea and vomiting, aggravated by food and partially relieved by sitting up and leaning forward. Physical examination reveals low grade fever, tachycardia and hypotension. Jaundice may also be found infrequently. Cullen sign (periumbilical discoloration) and Grey Turner sign (flank discoloration) indicate severe necrotizing pancreatitis.

Table 18.2 Causes of acute pancreatitis.

| Common (75% of cases) | Uncommon |

| Alcohol abuse | Drugs |

| Gallstone disease | Sulfonamides |

| Idiopathic | Tetracyclines |

| Valproate | |

| Didanosine | |

| Estrogens | |

| Exenatide | |

| Metabolic disorders | |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | |

| Hypercalcemia | |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | |

| Infections | |

| Mumps, Coxsackie and HIV viruses | |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | |

| Trauma | |

| Abdominal injury | |

| Surgery, including ERCP | |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Hereditary relapsing pancreatitis | |

| Pancreatic cancer | |

| Connective tissue diseases | |

| Pancreas divisum |

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Commonly found metabolic abnormalities include hyperglycemia, hypocalcemia, hyperlipidemia, hypoalbuminemia and coagulation disorders [2]. Serum levels of amylase and lipase are elevated, but these are neither sensitive nor specific. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows edema of the pancreas. Loss of the normal enhancement on dynamic CT scanning indicates pancreatic necrosis.

Most patients with acute pancreatitis develop transient hyperglycemia, which mostly results from a rise in glucagon levels rather than from β-cell injury [3]. Hyperglycemia is usually mild and resolves within days to weeks without needing insulin treatment. Permanent diabetes is rare and occurs mostly in cases with fulminant disease and multiorgan failure, in whom the incidence approaches 25% [4]. Blood glucose levels exceeding 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) during the first 24 hours indicate a poor prognosis [5].

Non-specific elevations of serum amylase and lipase may also be found in diabetic ketoacidosis [6]. Acute pancreatitis, however, may affect up to 11% of patients with ketoacidosis, usually with mild or even no abdominal pain [5].

Chronic pancreatitis

This condition is characterized by progressive and irreversible destruction of the exocrine pancreatic tissue, leading to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and varying degrees of glucose intolerance which often require insulin. The causes of chronic pancreatitis vary according to the geographic location (Table 18.3).

Table 18.3 Causes of chronic pancreatitis.

| Common (90% of cases) | Rare |

| Alcohol abuse | Hereditary relapsing pancreatitis |

| Idiopathic | Obstructive chronic pancreatitis |

| Tropical calcific pancreatitis |

Alcohol abuse accounts for most of the cases (>85%) in Western populations. Alcohol alters the composition of pancreatic secretions, leading to the formation of proteinaceous plugs that block the ducts and act as foci for calculi formation. Tropical pancreatitis is a distinct form of the disease that is not associated with excessive alcohol intake and is prevalent in the developing world [7].

Hereditary chronic pancreatitis is a rare entity, inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. Mutations in a number of genes have been implicated including PRSS1 (encoding cationic trypsinogen), SPINK1 (serine protease inhibitor, Kazal type 1) and CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) [8–11].

Obstructive chronic pancreatitis is a rare condition that follows occlusion of pancreatic ducts by tumors, scarring, pseudocysts or congenital anomalies. Stones are not seen. Surgery or endoscopic dilatation may occasionally be curative.

Idiopathic pancreatitis, which accounts for 10–20% of all cases, affects two distinct age groups, one with onset at 15–25 years and the other at 55–65 years [12]. Cigarette smoking is a risk factor and mutations in specific genes have also been postulated [11,13,14].

Epidemiology

Chronic pancreatitis is prevalent worldwide. In Western countries, the incidence is about 4 cases per year per 100 000 population [15,16]. Tropical chronic pancreatitis is confined to tropical and subtropical regions of the world.

Pathologic features

The term chronic calcific pancreatitis accurately describes the pathologic changes in over 95% of cases of chronic pancreatitis in Western countries. The ductal and acinar lumina are filled with proteinaceous plugs which later calcify, forming small stones composed chiefly of calcium carbonate or calcite. Huge stones can occur but are more characteristic of tropical pancreatitis. The stones are found diffusely throughout the affected organ. Microscopically, there is atrophy of the ductal epithelium and stenosis of the ducts, associated with patchy fibrosis. There may also be foci of necrosis, with infiltration by lymphocytes, plasma cells and histiocytes [17]. Ultimately, the pancreas shrivels and develops an opaque capsule that may adhere to surrounding organs.

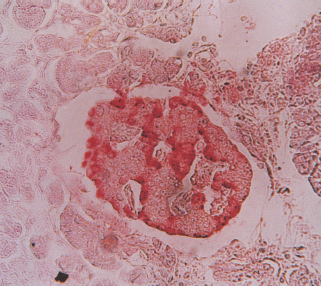

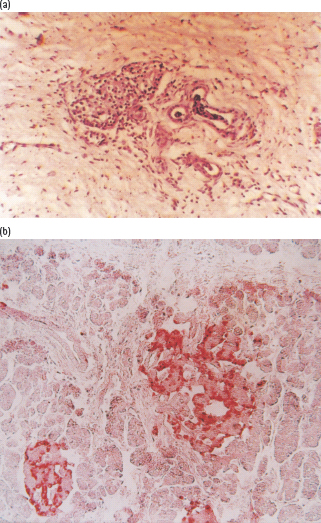

As fibrosis progresses, the acini atrophy and eventually disappear, leaving clusters of islets surrounded by sclerosed parenchyma. Neoformation of islet cells from ductal tissue can occur (nesidioblastosis) (Figure 18.1). Immunohistochemistry studies reveal generalized decrease in the number of islets, accompanied by overall reduction in β-cell density and insulin immunoreactivity which correspond to disease duration and C-peptide levels (Figure 18.2; Table 18.4) [18,19].

Figure 18.1 Nesidioblastosis, from a case of fibrocalculous pancreatic diabetes, showing islet tissue arising from ductal remnants. Stain aminoethylcarbazole; magnification ×40.

Figure 18.2 Histologic features of chronic pancreatitis, from cases of fibrocalculous pancreatic diabetes. (a) Exocrine tissue is entirely replaced by dense fibrosis that spares the islets. Hematoxylin and eosin stain; magnification × 40. (b) A hyperplastic islet. Section immunostained for insulin; magnification × 40.

Table 18.4 Islet cell changes in chronic pancreatitis [25].

| Cell type | Changes observed |

| β-cells | Decreased numbers (40% below controls) |

| α-cells | Increased numbers |

| β-cells:α-cell ratio | 0.6–2.5 (controls, 3.0–3.5 |

| PP cells | Increased numbers |

| δ (D) cells | Unchanged |

Clinical features and diagnosis

Abdominal pain is the predominant symptom and the usual reason for seeking medical care. The pain is usually steady, boring and agonizing and located in the epigastrium or left hypochondrium with radiation to the dorsal spine or the left shoulder. Bending forward or assuming the knee–chest position relieves the pain. The cause of the pain is unknown, but may relate to increased intrapancreatic or intraductal pressure, or to ischemia of the pancreas. It tends to remit and relapse and follows an unpredictable course. The development of end-stage pancreatic disease is associated with disappearance of the pain in many cases.

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency may manifest with steatorrhea and features of fat-soluble vitamin deficiency. Steatorrhea may not be apparent on a low-fat diet. The combination of oily and greasy stools with diabetes should raise the suspicion of chronic pancreatitis.

Investigations

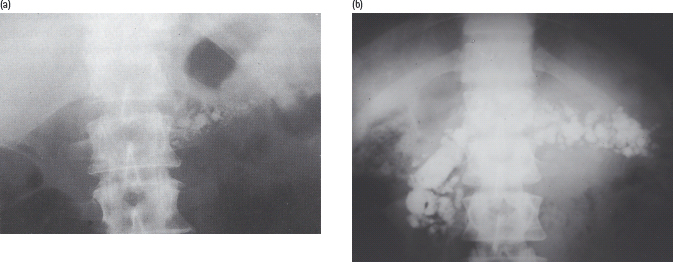

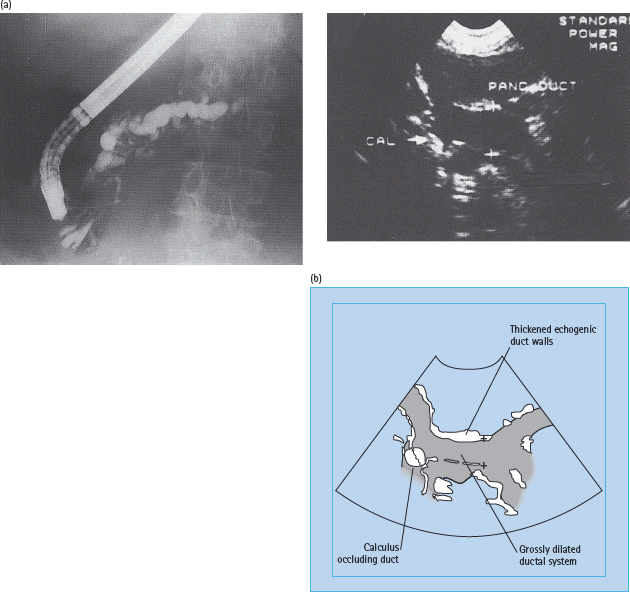

Demonstration of pancreatic calculi on a plain X-ray of the abdomen is diagnostic (Figure 18.3). In cases where obvious calculi cannot be found, ultrasonography, CT scanning or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) will help to confirm the diagnosis. ERCP is considered the gold standard and usually reveals irregular dilatation of the pancreatic ducts with filling defects caused by stones (Figure 18.4). CT scanning shows patchy increases in parenchymal density and, ultimately, atrophy of the gland.

Figure 18.3 Pancreatic calculi, showing characteristic patterns in (a) alcoholic chronic pancreatitis, and (b) fibrocalculous pancreatic diabetes.

Figure 18.4 Investigations in chronic pancreatitis. (a) Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram, showing dilatation and irregularity of the pancreatic ductal system in a patient with alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Courtesy of Professor Jonathan Rhodes, Liverpool. (b) Ultrasound scan of the pancreas from a patient with fibrocalculous pancrdeatic diabetes, demonstrating highly echogenic parenchyma and duct walls (fibrosis), grossly dilated ducts and calculi. Courtesy of Dr. S. Suresh, Chennai, India.

Exocrine pancreatic function can be assessed by measuring the urinary excretion of compounds that are liberated in the gut by pancreatic enzyme action on orally ingested precursors such as NBT-PABA (para-aminobenzoic acid) or fluorescein dilaurate (pancreolauryl). Screening tests of pancreatic enzymes (fecal chymotrypsin, fecal elastase) are also used as they are simpler to perform but are less specific. Measurement of pancreatic output (via a tube placed in the duodenum) following ingestion of the Lundh test meal may also be helpful. Serum amylase is usually normal, except during acute attacks.

Diabetes in chronic pancreatitis

Abnormal glucose tolerance and diabetes complicate around 40–50% of cases of chronic pancreatitis. Unlike acute pancreatitis, the cause here is damage to the β-cells, owing to loss of trophic signals from the exocrine tissue [1,20]. The diabetes is of insidious onset and usually occurs several years after the onset of pain. The prevalence has been assessed at 60% after 20 years [21]. Half or more of patients require insulin for optimal glycemic control [22,23], but ketoacidosis is rare, even if insulin is withdrawn. Possible explanations include better preservation of β-cell function (compared with type 1 diabetes; T1DM) [24], reduced glucagon secretion and lower body stores of triglyceride, the major substrate for ketogenesis [24,25]. On account of the lower glucagon reserve, these patients are also prone to severe and prolonged hypoglycemia, and often diabetes is difficult to control with wide fluctuations of blood glucose levels.

Chronic diabetic complications

It was originally thought that patients with pancreatic diabetes were not at increased risk of microvascular complications. It has now been shown that retinopathy [26], nephropathy [27] and neuropathy [28] occur in these patients at frequencies similar to those with type 2 diabetes (T2DM). The risks of macrovascular complications, however, are relatively low. This may partly be explained by the low blood lipid levels that often accompany the malnutrition commonly seen in these patients [29].

Management of diabetes in chronic pancreatitis

Removal of obvious causes such as alcohol and hypertriglyceridemia will help to prevent progression of the damage to the gland.

Pain can be very difficult to manage. Measures include total abstinence from alcohol, dietary modification (small frequent meals with low fat content), analgesics and the somatostatin analogue, octreotide, which suppresses pancreatic exocrine secretion. In a subgroup of patients, massive doses of non-entericcoated preparations of pancreatic enzymes have been shown to reduce pain. Surgical interventions include sphincterotomy, internal drainage of pancreatic cysts, endoscopic removal of calculi (via ERCP), insertion of duct stents and denervation procedures. Total resection of the pancreas followed by whole pancreas or islet cell transplantation may be an option for intractable cases.

Malabsorption can be effectively treated with a low fat diet with pancreatic enzyme supplements (along with histamine H2 blocker or proton pump inhibitor to block gastric acid secretion) taken at meal times.

Diabetes can be managed along conventional lines, with a few caveats. High carbohydrate and protein intakes are encouraged along with fat restriction in order to prevent steatorrhea. Over 80% of patients require insulin; however, the required doses are typically low, around 30–40 units/day [22,23]. Diabetic control is often difficult to achieve, with frequent and severe hypoglycemia; reduced glucagon secretion may be responsible.

Tropical calcific pancreatitis

This is a distinct variety of chronic pancreatitis seen predominantly in low and middle income countries in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world [30,31]. This entity was first reported in 1959 by Zuidema [31] in patients from Indonesia. Later on, the disease was reported from several countries in Africa and Asia. The highest prevalence appears to be in Southern India, particularly in the states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu [32].

The disease usually starts in childhood with recurrent abdominal pain and during adolescence progresses to large pancreatic calculi and ductal dilatation (Figures 18.3 and 18.5). By adulthood, frank diabetes is found in more than 90% of patients [33]. Nevertheless, it remains a rare cause of diabetes, constituting less than 1% of all cases of diabetes even in regions where it is most prevalent [34]. A recent study in urban southern India reported a prevalence of 0.36% among subjects with self-reported diabetes and 0.019% among the general population [35].

Figure 18.5 Calcite stones of various sizes removed from the pancreas of a patient with fibrocalcuous pancreatic diabetes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree