Outbreak Epidemiology

Diane M. Dwyer

Carmela Groves

David Blythe

INTRODUCTION

Outbreak epidemiology is the investigation of a disease cluster or epidemic with the goal of controlling or preventing further disease in a population. The word epidemic—defined as an increase in the number of cases of a disease above what is expected—is derived from the Greek epi and demos, meaning “that which is upon the people.” This meaning enriches our understanding of epidemics by emphasizing the burdensome toll they have on a population or “a people.” This definition also allows us to realize that epidemics are not always caused by infectious agents. Many other hazards, such as chemicals or physical conditions, can cause unusually high numbers of cases of disease in a given population. Regardless of the etiology of the disease, the techniques used to investigate and control outbreaks are generally similar.

Accounts of outbreaks have been recorded throughout the centuries. Cholera, influenza, malaria, smallpox, and the plague are extensively documented as causes of epidemics and pandemics that have altered the outcome of wars, disrupted political structures, killed millions of people, and affected the lives of countless others.1 The prevention of disease through measures such as improved sanitation, as well as isolation and quarantine, was recognized even before the causes of these diseases had been identified.

New challenges continue to arise in the control of infectious diseases. Public health officials and healthcare providers face the emergence of new diseases and the reemergence of diseases that were no longer thought to be a threat to the public’s health.2 The threat of the use of biologic agents or their toxins (e.g., anthrax, plague, botulism, and smallpox) as weapons of bioterrorism has resulted in increased attention being paid to the possibility of outbreaks caused by intentionally released agents.3 Changes in the environment; industrial practices; agriculture and food processing; international transportation of people, foods, and goods; and changes in human behaviors have increased the risk of disease and the speed at which communicable disease can spread.

Concurrently, the number of people at increased risk of infection and the density of human populations have increased. People with immune dysfunction (e.g., because of human immunodeficiency virus infection, rheumatologic conditions, hematologic conditions, organ transplantation, cancer chemotherapy, or chronic use of corticosteroids), infants, and the elderly are more susceptible to infectious diseases, including those caused by infectious agents that may not have been medical concerns in the past. These compromised individuals may present with lower temperature or with unusual symptoms that complicate the diagnosis, and their infections may be more difficult to treat. Immunosuppression may also increase the infectiousness of the individual, either by increasing the number of infectious organisms that the individual sheds or by increasing the length of time during which the individual is infectious.4 Meanwhile, the increasing density of the human population, especially in some developing nations, creates situations that foster the spread of new and old infectious diseases.

Nevertheless, the advantage is not all to the microbes. Advances in laboratory techniques, medical interventions (such as antibiotics), sanitation, technology, and epidemiology have increased our ability to identify and control infectious diseases.5

The news media and other media such as the Internet and social media have enhanced outbreak awareness. Names of organisms and events such as Escherichia coli O157:H7, Ebola virus, Cryptosporidium, group A Streptococcus (“the flesh-eating bacteria”), antibiotic-resistant organisms (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA]), severe acute respiratory syndrome, and

pandemic influenza conjure up reports of outbreaks that have been brought to the attention of the public through the media. That E. coli O157:H7 can cause fatal hemolytic uremic syndrome, especially in children, was demonstrated in U.S. outbreaks caused by contaminated ground beef and fresh spinach and in the Japanese outbreak caused by contaminated radish sprouts.6, 7 and 8 The speed at which international diseases could become threats to U.S. citizens was underscored by the reports of Ebola virus isolated in monkeys in Reston, Virginia.9 Reports of outbreaks involving strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, MRSA, and Streptococcus pneumoniae that are resistant to antibiotics have raised public awareness of the danger of inappropriate or excessive antibiotic use. Investigation of such events allows epidemiologists to identify risk factors and to determine preventive measures that will limit and control the spread of disease.

pandemic influenza conjure up reports of outbreaks that have been brought to the attention of the public through the media. That E. coli O157:H7 can cause fatal hemolytic uremic syndrome, especially in children, was demonstrated in U.S. outbreaks caused by contaminated ground beef and fresh spinach and in the Japanese outbreak caused by contaminated radish sprouts.6, 7 and 8 The speed at which international diseases could become threats to U.S. citizens was underscored by the reports of Ebola virus isolated in monkeys in Reston, Virginia.9 Reports of outbreaks involving strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, MRSA, and Streptococcus pneumoniae that are resistant to antibiotics have raised public awareness of the danger of inappropriate or excessive antibiotic use. Investigation of such events allows epidemiologists to identify risk factors and to determine preventive measures that will limit and control the spread of disease.

An outbreak may occur for a variety of reasons, including poor food handling practices and personal behaviors, environmental contaminants, and intentional acts of terrorism. An epidemiologist must investigate cases of disease with an awareness of all these possibilities. However, the basic techniques in investigation remain the same. This chapter reviews the methods used to investigate and control outbreaks of infectious disease.

SURVEILLANCE AND OUTBREAK DETECTION

Outbreaks may come to the attention of health professionals through a report from a doctor’s office, a hospital, a nursing home, a laboratory, or even a patient’s call to the health department. Alternatively, outbreaks may be recognized through analysis of routine public health surveillance reports of individual cases of disease or through active surveillance for specific syndromes. Refer to the chapter on surveillance for additional information and methods relating to surveillance of diseases.10

Each state has its own individual laws, regulations, or both that govern which diseases and conditions are reportable and specify the method and timing of reporting; thus there are some variations across states. Nevertheless, reporting of outbreaks is generally included in most states’ disease reporting systems. The list of diseases for inclusion in national surveillance is established by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) and the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and is updated yearly.11 States then voluntarily report to the CDC cases of diseases that are on the “nationally notifiable” list.

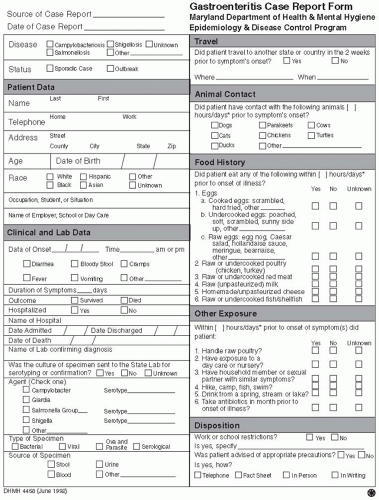

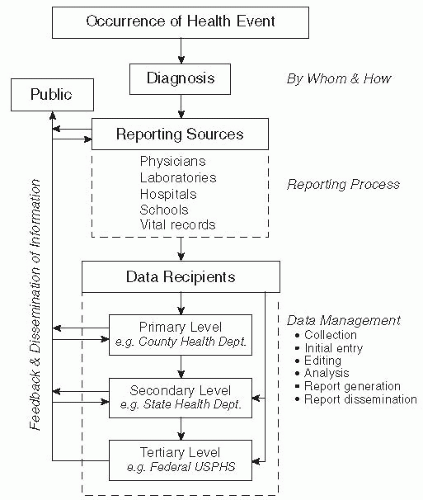

In traditional passive public health surveillance, reports can originate from a variety of sources, including physicians, laboratories, hospitals, schools, childcare centers, vital records departments, and other facilities (Figure 5-1).12 Cases are generally reported to state or local health departments with information such as diagnosis, name, age, gender, address, and date of onset. Reports may also include other information, such as laboratory results, treatment, occupation, setting of occurrence, and risk factors (Figure 5-2 and Figure 5-3).13, 14 Case reports, without personal identifiers, are then transmitted weekly from states to the CDC for inclusion in national summary data published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.15

Information collected as part of the disease reporting system is compiled and evaluated at local, state, and federal levels. Outbreaks are often first identified at the local or state health department level. Multistate outbreaks can sometimes be detected at the federal level by identification of increases in routine surveillance reports to CDC, the Foodborne Disease Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet), or early detection systems such as PulseNet. FoodNet, a collaborative project among CDC, 10 state health departments, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), consists of active surveillance for foodborne diseases; surveys of laboratories, physicians, and the general population; and population-based epidemiologic studies. Personnel in state health departments contact local laboratories to obtain reports of selected foodborne infections diagnosed in residents of these areas.16 PulseNet, whose activities are also coordinated by CDC, is a network of public health and food regulatory agency laboratories that perform molecular subtyping of foodborne bacteria; this information is submitted electronically to CDC and maintained in a standardized database. This national database allows for rapid comparison of molecular patterns.17 Detection of outbreaks can also occur through specialized analytic routines for aberration detection or other systems that use early indicators such as “syndromic surveillance”10, 18 or surveillance for syndromes of diarrhea, rash, or respiratory symptoms.

The information collected as part of the surveillance network is made available for additional epidemiologic evaluation. These data represent years of continuous data collection and, therefore, can be used to examine disease trends in a community.

However, these data are not collected primarily for the conduct of research or study. Rather, surveillance data are collected to detect disease, to describe cases found in a specific community, and to guide public health actions. Ideally, epidemiologic research data would be collected to address specific hypotheses and to produce generalizable knowledge. Surveillance data are collected according to those procedures that maximize consistency and minimize the barriers to reporting. For example, surveillance databases often include data collected by passive reporting and have only minimal information on cases. In contrast, more detailed data collection may be required for research purposes to examine specific hypotheses, such that employees may be dedicated to managing complex data collection systems. Because of these differences, surveillance data may be inadequate to answer some epidemiologic questions. Even so, surveillance data are an excellent source of information to establish baseline rates and detect outbreaks, to identify new problems or trends in a community, to guide public health actions, to evaluate programs, to assist health professionals in estimating the magnitude of a health problem, and to identify possible hypotheses that can be explored by enhancing surveillance or by a research study.

However, these data are not collected primarily for the conduct of research or study. Rather, surveillance data are collected to detect disease, to describe cases found in a specific community, and to guide public health actions. Ideally, epidemiologic research data would be collected to address specific hypotheses and to produce generalizable knowledge. Surveillance data are collected according to those procedures that maximize consistency and minimize the barriers to reporting. For example, surveillance databases often include data collected by passive reporting and have only minimal information on cases. In contrast, more detailed data collection may be required for research purposes to examine specific hypotheses, such that employees may be dedicated to managing complex data collection systems. Because of these differences, surveillance data may be inadequate to answer some epidemiologic questions. Even so, surveillance data are an excellent source of information to establish baseline rates and detect outbreaks, to identify new problems or trends in a community, to guide public health actions, to evaluate programs, to assist health professionals in estimating the magnitude of a health problem, and to identify possible hypotheses that can be explored by enhancing surveillance or by a research study.

Figure 5-1 The major steps in a public health surveillance system. Reproduced from Public Health Surveillance. Halperin W and Baker E, eds., p. 30, © 1992, John Wiley & Sons. |

Because outbreak epidemiology is concerned primarily with the control of disease, the sensitivity of the surveillance or reporting network is of paramount importance. If cases of disease are not reported, an outbreak may not be detected or may continue unabated.

OUTBREAK INVESTIGATION

Based on experience with outbreak investigations, a series of steps has been identified that can be used to guide any epidemiologic field investigation.19, 20, 21, 22, 23 and 24 The outbreak epidemiologist is the “disease detective” of public health. Outbreak investigation is a systematic process of evaluating data to form hypotheses, and then collecting additional data to test the hypotheses. An understanding of the basic steps of outbreak epidemiology can guide the investigator in determining which types of data to collect and how to collect them; each outbreak is unique, however, so it is also important to be aware of how an outbreak

under current investigation differs from previous outbreaks.

under current investigation differs from previous outbreaks.

Most commonly, outbreak investigations, including laboratory support, occur at the local or state public health level. Generally, the CDC is consulted in multistate outbreaks or in outbreaks of diseases that require resources or skills that state and local agencies are unable to provide. The laboratory and epidemiologic capabilities of the CDC are enlisted to assist with domestic and international disease outbreaks of unusual etiology or of major public health significance.

Local and state health departments decide to conduct an outbreak investigation based on health regulations and/or policies and on the professional judgment of staff regarding the outbreak and its

public health impact or implications. Regardless of the etiologic agent, the setting in which the disease may have been transmitted, or the population at risk, it is possible to summarize the basic steps and goals of the investigation. The primary motivation of any outbreak investigation is to control the spread of disease within the initial population at risk or to prevent the spread to additional populations. Many outbreaks occur in defined populations, groups, or settings, such as a foodborne outbreak at a wedding banquet or a potluck dinner. Fortunately, these outbreaks generally have a single exposure, where the contaminated vehicle may have been consumed or discarded before the first cases are apparent and no more people are at risk. In other outbreaks, where transmission may be ongoing, such as legionellosis among hospitalized patients or disease caused by commercial products or fruits and vegetables, the epidemiologic investigation must be initiated quickly and control measures implemented to halt further transmission. Prevention of disease requires that the investigation identify the etiologic agent, its source,

the mode of transmission, and the vehicle. The information learned during the course of investigation is important in preventing and controlling outbreaks of the same disease in the future and may be useful in linking sporadic cases to the same source.

public health impact or implications. Regardless of the etiologic agent, the setting in which the disease may have been transmitted, or the population at risk, it is possible to summarize the basic steps and goals of the investigation. The primary motivation of any outbreak investigation is to control the spread of disease within the initial population at risk or to prevent the spread to additional populations. Many outbreaks occur in defined populations, groups, or settings, such as a foodborne outbreak at a wedding banquet or a potluck dinner. Fortunately, these outbreaks generally have a single exposure, where the contaminated vehicle may have been consumed or discarded before the first cases are apparent and no more people are at risk. In other outbreaks, where transmission may be ongoing, such as legionellosis among hospitalized patients or disease caused by commercial products or fruits and vegetables, the epidemiologic investigation must be initiated quickly and control measures implemented to halt further transmission. Prevention of disease requires that the investigation identify the etiologic agent, its source,

the mode of transmission, and the vehicle. The information learned during the course of investigation is important in preventing and controlling outbreaks of the same disease in the future and may be useful in linking sporadic cases to the same source.

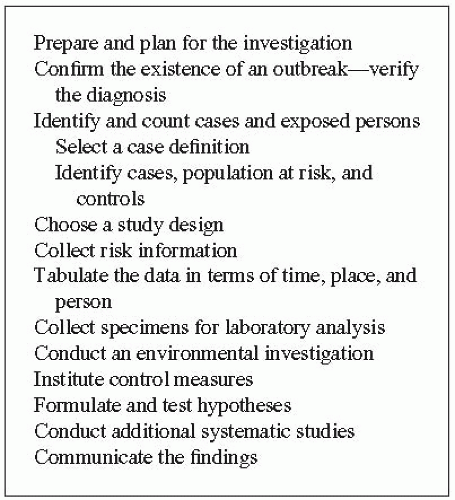

The steps for conducting an outbreak investigation are outlined in Figure 5-4.24 A hallmark of outbreak epidemiology is that these steps do not necessarily proceed in a specified sequence. In actuality, several steps in the investigation usually occur simultaneously. These steps are tailored to the situation and depend on factors such as the urgency of implementing control measures; the availability of staff, resources, and time; and the difficulty of obtaining the data. Multiple persons may perform activities concurrently. Action and reaction proceed based on new and cumulative information. Because implementation of control measures is central to the goal of any outbreak investigation, measures to control the spread of disease must be implemented early in the investigation and may be altered as data are collected and analyzed.

Prepare and Plan for the Investigation

Preparing for the outbreak investigation and planning the investigation are critical to a successful outcome. It is imperative to identify the investigation team members, to assign responsibilities, to begin the investigation as soon as possible, and to conduct progress meetings at regular intervals. The multidisciplinary investigative team may include epidemiologists, healthcare professionals, laboratorians, and sanitarians, among others. Often, the personnel who initiate an outbreak investigation are predetermined: health departments, hospitals, schools, or nursing homes commonly have personnel responsible for disease control who are dedicated to outbreak activities when the need arises. For many small-scale epidemiologic investigations, the initial outbreak “team” will be a single epidemiologist or other professional who will assess the situation and determine what needs to be done. As the investigation proceeds, personnel may need to be added or reassigned to carry out the investigation.

Successful investigations require effective communication at all levels of authority. Summaries or specific findings need to be shared on an ongoing basis (as appropriate and as allowed by confidentiality laws) with critical individuals and parties, such as facilities or businesses where the outbreak occurred, colleagues, healthcare providers, other regulatory agencies, the media, and the public. In the United States, communication among the local health department, state health department, and federal agencies such as the CDC, the FDA, and the USDA is routine in multijurisdictional outbreaks or outbreaks of national importance, and helps ensure that roles and responsibilities are clear from the outset of the investigation onward.

Confirm the Existence of an Outbreak: Verify the Diagnosis

An early step of any outbreak investigation is to confirm the existence of an outbreak. Important questions to ask include the following: Are there cases in excess of the expected baseline rate for that disease and setting? Is the reported case actually a case of the disease or a misdiagnosis? Do all (or most) of the “suspect cases” have the same infection or similar manifestations?

For some diseases, a single case is sufficient to warrant an outbreak investigation. For example, anthrax, human rabies, foodborne botulism, polio, and bubonic plague are very rare in the United States and are serious diseases; thus an investigation would be initiated with a single suspected case. This is illustrated by the single case of anthrax reported in October 200125; the report initiated the full-scale investigation of the intentional release of anthrax in multiple locations across the eastern United States. Investigators must also be aware of the background level of disease in a population under surveillance.

For example, malaria infection acquired in the United States would be treated quite differently than a case of malaria acquired in sub-Saharan Africa. A review of existing state, local, or facility baseline rates of disease can be compared with the current case number. It is important to take into account the population in which the cases are occurring. Several cases of diarrhea in a nursing home may be a common occurrence, whereas the same number would represent an outbreak if they occurred clustered in time among healthy adults after a picnic. When trying to determine whether more cases of an illness are occurring than would be expected, it is also important to consider seasonal variations in disease rates. Influenza outbreaks can be expected to occur in the winter, whereas bacterial enteric diseases are more common in the summer.

For example, malaria infection acquired in the United States would be treated quite differently than a case of malaria acquired in sub-Saharan Africa. A review of existing state, local, or facility baseline rates of disease can be compared with the current case number. It is important to take into account the population in which the cases are occurring. Several cases of diarrhea in a nursing home may be a common occurrence, whereas the same number would represent an outbreak if they occurred clustered in time among healthy adults after a picnic. When trying to determine whether more cases of an illness are occurring than would be expected, it is also important to consider seasonal variations in disease rates. Influenza outbreaks can be expected to occur in the winter, whereas bacterial enteric diseases are more common in the summer.

As an outbreak investigation is initiated, it is important that the diagnosis be confirmed—and that the specificity of the case definition is good. This involves a review of available clinical and laboratory findings that support the diagnosis and often entails obtaining more clinical or laboratory information than is initially reported. For example, before deciding that Neisseria meningitidis is the organism causing meningitis, the investigator must confirm that the specimen was taken from a sterile body site (e.g., blood or cerebrospinal fluid), rather than from a body site where the organism might be a part of the normal flora (e.g., throat). Several cases of rash illness in a school may signal a chickenpox (varicella) outbreak if the diagnosis is confirmed, or they may simply represent a cluster in time of rashes of different etiologies and, therefore, not an outbreak.

Identify and Count Cases and Exposed Persons; Select a Case Definition

A case definition is needed to identify and count cases in a consistent way so as to determine who may be affected by the outbreak. Components of the case definition may include information about time and place of exposure, laboratory findings, and clinical symptoms. Case definitions should be applied consistently and investigators should be clear and specific about any component of a case definition. However, it is also important to appreciate that case definitions might be refined or different case definitions used at different points in an investigation.

In general during an outbreak investigation, the initial case definitions used are broader rather than narrow. For example, an early definition in a foodborne outbreak might take the following form: “A case of illness is defined as any diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, headache, or fever that developed after attending the implicated event.” This broad definition neither assumes that all cases will have the same symptoms, nor does it make any assumptions about the risk factors for illness (e.g., those who ate a particular food or had contact with specific people). This initial case definition has greater emphasis on sensitivity than on specificity. As additional information is gathered about the cases, the nature of exposure, and the symptoms, the case definition can be refined as appropriate to improve the specificity. A subsequent case definition may state: “A case of illness is defined as diarrhea or vomiting with onset within 96 hours of consuming food served at the implicated meal.” This refined definition is more specific and will serve to exclude unrelated cases of gastroenteritis or other illnesses, so that the etiologic exposure is more reliably identified.

In outbreak investigations, as in routine surveillance, cases of disease are commonly separated into those that are confirmed and those that are probable. Confirmed cases are generally those with laboratory findings for the organism (such as a positive culture or antigen test, antibody titer rise, or a positive polymerase chain reaction [PCR]), and probable cases are those who have certain symptoms meeting a clinical case definition but without laboratory confirmation.26 For some diseases (e.g., pertussis), a case is considered confirmed if a compatible clinical illness is present and the case is epidemiologically linked to a laboratory-confirmed case.

Frequently, laboratory confirmation is complicated by a number of factors: People may test positive for the organism for only a short time around the acute phase of illness; some pathogens produce toxins for which there is no laboratory test; the organism may be shed only transiently or intermittently; antibody tests may be difficult to interpret if individuals have been exposed to the pathogen in the past; persons with mild disease may not seek medical attention and, therefore, will not have laboratory tests completed; and persons may be treated at different medical facilities with different laboratory procedures. If laboratory confirmation is important and the outbreak is identified rapidly enough, the outbreak investigation team may want to collect samples promptly or obtain multiple specimens to confirm the initial cases so as to establish the agent responsible for the outbreak. However, this commitment of resources may not be necessary to confirm every case during the investigation. If the case definition can be made sufficiently specific without the use of laboratory tests, collecting and testing specimens may simply represent an additional burden and expense to the exposed population and the investigation team.

Identify Cases, Population at Risk, and Controls

During the outbreak investigation, the investigator should seek to identify additional cases not known or reported at the time of the initial report. Case-finding techniques used to enhance surveillance for additional cases include reviewing existing surveillance data (e.g., morbidity reports received by a health department or monthly summaries of illness) for other cases of the same illness; reviewing outbreak-complaint logs kept by a local health department; reviewing past laboratory data; surveying hospitals, emergency rooms, or physicians; and obtaining credit card receipts or shopper card information. In certain outbreaks, such as those occurring in a restaurant where there is no list of attendees, a useful technique for finding additional cases and controls is questioning known cases to identify others who were in attendance. (See the section on case-control studies.) In some situations, other techniques might be appropriate, such as the use of the Internet, social media, or other media notices.

The investigator should identify the population at risk or the exposed group in which to conduct expanded surveillance for cases. The exposed group or cohort will vary depending on the setting, and it may not always be possible to identify or enumerate the entire population at risk. Examples of exposed groups include a group of persons who attended a wedding banquet; all people who dined in a food establishment on one particular day; children who attend a daycare center, their household members, and the employees of the center; and all persons who were exposed to an implicated manufactured lot or shipment of a commercial product. The exposed population, therefore, can range from as few as one person to as many as thousands of individuals in multiple locations. Records maintained by the establishments involved can facilitate identification of persons at risk. Party invitation lists, guest books, credit card receipts, and customer lists are often available and are very helpful to investigators. Of course, individuals located by release of their names from credit card receipts may be concerned about how the investigators got their names and may fear credit card theft! Explaining the purpose of the investigation and how information will be handled may be vital to securing their cooperation in the investigation. State and federal public information laws vary in terms of which information is to be held confidential in outbreak situations.

Choose a Study Design

During an outbreak investigation, the study design is chosen based on factors such as the size and availability of the exposed population, the speed with which results are needed, and the available resources. The characteristics of the exposed population are generally determined after interviewing a few of the initial cases. Exposed populations fall into four broad categories: small enumerable exposed groups, large enumerable exposed groups, large or small groups where the exposure situation can be pinpointed but where the exposed population cannot be enumerated, and cases of disease where the exposed population is not known or identifiable. The study design that is chosen will then dictate the appropriate analysis and hypothesis testing, as discussed next.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree