14 Open Surgical Techniques in Colorectal Cancer

Introduction

Surgery remains the primary modality of treatment for malignancies of the lower gastrointestinal tract. Based on experience, an estimated 90% to 92% of patients with colon cancer and 84% of patients with rectal cancer are treated surgically. The chance of cure with surgery as the sole treatment modality decreases with increasing tumor depth penetration and lymph node involvement.1 Variations in surgical techniques exist in the treatment of colorectal cancer and can be best evaluated by studying rates of local recurrence and survival. The wide range in recurrence rate (4%–55%) is evidence that the type of surgical technique significantly affects cancer outcome, especially for rectal cancer. Based on the latter findings, the National Cancer Institute ([NCI] Bethesda, Maryland) systematically reviewed the literature and drafted guidelines to reduce surgical variation and to help standardize documentation. These guidelines helped minimize inconsistencies in staging patients with colorectal cancer and enhanced surgical quality control in 2001. Along with the surgical principles governing them, these guidelines are incorporated into the remainder of this chapter.

Surgical Oncologic Principles: Historical Perspective

In the 1960s, the idea that modifying surgical techniques to consider oncologic principles can have a positive influence on survival in colorectal cancer began to formulate. Turnball and associates,2 in a much-criticized study in 1967 at the Cleveland Clinic Hospital, retrospectively compared the outcomes of patients who had resections for malignancy using the no-touch isolation technique with the outcomes of patients who underwent more traditional resections. The no-touch isolation technique involves the ligation of the draining vessels at their origin early in the dissection, then the proximal and distal bowel to the lesion is ligated, and finally the tumor is mobilized. This procedure isolates the tumor, which prevents intraluminal and hematogenous spillage that would otherwise occur during manipulation of the tumor. The study concluded that patients with no-touch oncologic resection had a better 5-year survival rate.

In 1998, Wiggers and associates3 compared the no-touch technique with the conventional technique in a randomized prospective trial. The trial found no significant difference in 5-year survival rates between the no-touch group and the conventional group, but there was a trend toward better cancer-related survival in the former group. The trials emphasized the fact that operative techniques and following oncologic principles are essential; however, the no-touch technique is no longer followed. Since then, evidence increasingly suggests that the quality of the oncologic outcome is directly proportional to the surgical team’s adherence to NCI oncologic guidelines. Most of the evidence comes from rectal cancer, but the correlation holds for colon cancer. The German Study Group Colo-Rectal Carcinoma trial showed that the surgeon is a critical variable in determining locoregional recurrence rate and morbidity.4

The oncologic principles involving resection include:

Oncologic Principles for Bowel Resection and Margins

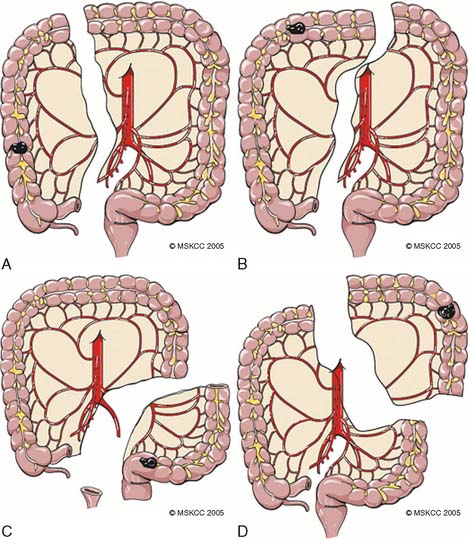

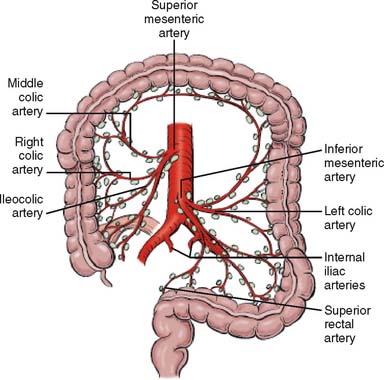

Operative planning for resection for colonic malignancy ideally should include radical en bloc removal of the blood supply and the draining of lymphatics at the level of the origin of the primary feeding arterial vessel. The vascular supply to the colon is demonstrated in Figure 14-1. The ultimate length of the resected bowel segment is dictated by the lymphovascular resection. Enker and associates5 recommend that resection of the distal and proximal margin should be at least 5 cm from the tumor, since the local recurrence rate is 6.9% for margins greater than 5 cm and 20% for those less than 5 cm in Dukes stage B. The bowel margins should be wide enough to limit intraluminal and pericolic recurrence. Generally accepted surgical principles recommend resection margin distance of 5 to 10 cm.

Figure 14-1 Lymph node and blood supply of colon and rectum.

(From Greene FL, Page DL: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002, p 123.)

Guidelines in the United States recommend ligation of the primary feeding artery at the level of its origin. Although the level of ligation of the primary feeding artery is still under debate, high ligation is favored based on results of studies that show improvement of 5-year survival rates with high versus low ligation. The following studies showed favorable 5-year survival rates with high ligation—all found in the article by Hida and colleagues6: Rosi and colleagues showed 77% versus 63% with low ligation, Bacon and colleagues found 73.6% versus 63.2%, and Slanetz and Grimson found 74.5% versus 65.8%. It is recommended that when the primary tumor is equidistant from two feeding vessels, both vessels should be excised at their origin.6

The drainage of the lymphatic system mirrors that of the vascular system. In colon carcinoma, there are two possible directions for lymphatic drainage: central along the mesenteric vessels and para-intestinal. Divide the major draining mesenteric vessel(s) at the point of origin with the accompanying lymphatic network to prevent regional lymphatic recurrence. For right colon resections, the length of ileum resected does not appear to affect local recurrence. Therefore, the shortest length of ileum should be resected to prevent malabsorption syndromes while ensuring adequate blood supply to the anastomosis.

Lymphadenectomy

Lymph node resection carries prognostic and therapeutic implications. The lymph node resection should be radical and removed en bloc. The lymph node dissection should be carried to the level of the origin of the primary feeding vessel. Colon cancer staging requires adequate analysis of lymph nodes to determine prognosis and further treatment. The 1990 Working Party report of the World Congress of Gastroenterology recommends that at least 12 lymph nodes must be evaluated. This recommendation was reiterated by an NCI sponsor panel of experts.7

A systemic review of evidence for the association between lymph node evaluation and surgical outcome in patients with colon cancer showed that the number of lymph nodes evaluated after surgical resection was positively associated with survival of patients with stage II and stage III colon cancer.8 Because of the high risk for recurrence of colon cancer, adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended for patients with lymph node metastases (stage III).

However, a population-based study by Baxter and associates9 found that only 37% of patients with colon cancer receive adequate lymph node evaluation during colon cancer staging. The two potentially modifiable influences are the completeness of lymph node evaluation by the examining pathologist and the adequacy of the surgical resection. The number of lymph nodes recovered has been identified as a potentially important measure of the quality of cancer care by many organizations. The proficiency of the surgeon and total hospital case volume are positively associated with the number of lymph nodes recovered. Patients in lower-volume hospitals were more likely to have fewer than seven lymph nodes detected. The experience of the pathologist and the technique of pathologic evaluation have also been shown to be important in lymph node recovery after adjusting for surgeon and tumor-related factors.

Guidelines in the United States recommend that nodes at the origin of the primary feeding artery (apical node) should be tagged for pathologic evaluation because the apical nodes have prognostic significance in addition to the number of nodes positive for disease in the specimens. The apical lymph node is defined as the “most proximal lymph node within 1 cm of vessel ligation at apex of vascular pedicle.”6,7,10 Multivariate analysis has shown that involvement of the apical lymph node is significantly associated with adverse outcome. The general recommendation for surgical resection of the colon is to ligate the primary feeding arterial vessel at the level of its origin and resect at least 5 cm of bowel on both sides. This technique should produce better patient prognosis and more accurate staging. A smaller extent of resection decreases the number of recovered nodes and increases the risk of under-staging.11,12

The concept of sentinel lymph node examination has been studied for colon cancer, but there is no uniformity in the definition of cellular burden, nor is there common agreement on how to clinically define relevant metastatic disease. Some studies have shown that the detection of immunohistochemistry (IHC) cytokeratin-positive cells in stage II (N0) colon cancer indicates a worse prognosis, whereas other studies have failed to show a survival difference. Until the use of sentinel lymph nodes and the detection of cancer cells by immunohistochemistry have been standardized and proved more effective than nodal dissection, the procedures recommended herein should be used.13,14

Colon

Surgical Preparation

Be thorough during the endoscopy to locate all lesions. The rate of synchronous colon cancers ranges from 2% to 11%, and the incidence of synchronous adenomatous polyps may be greater than 30%. In this case, as much colon length as possible should be preserved without compromise to the cancer resection. An alternative is subtotal colectomy with an ileorectal or ileosigmoid anastomosis rather than a multiple anastomosis.15

Extent of Resection

Right Colon

Right colon cancers account for up to 15% of primary colorectal cancers. Patients with adenocarcinoma involving the cecum or ascending colon who do not have hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) or other synchronous lesions should be treated with a right hemicolectomy. The standard extent of resection for various colon cancers has been defined. The ileocolic, right colic, and right branch of the middle colic arteries and veins should be ligated near their origin to ensure an adequate lymphadenectomy. For tumors of the cecum and the ascending colon, a right hemicolectomy that includes the right branch of the middle colic artery at its origin should be performed. For tumors of the hepatic flexure, an extended right colectomy that includes the entire middle colic artery is indicated (Fig. 14-2).

Step 2: Mobilization of the Right Colon.

Once the resectability is determined, the peritoneal, ileal, and lateral colonic attachments are incised. An incision is made in the peritoneal reflection attached to the lateral wall of the bowel, starting from the tip of the cecum upward to the region of the hepatic flexure. Sometimes the full thickness of the abdominal wall may require excision because of local spread of tumor. The entire hepatic flexure is mobilized as part of right hemicolectomy. The hepatocolic ligament contains small blood vessels, which can be divided with electrocautery. After the lateral attachments are divided, the right colon is lifted medially, and the loose areolar tissue lying under is dissected off gently. The right ureter should be identified when elevating the right colon. Care is also taken to avoid injury to the third portion of the duodenum toward the top of ascending colon. The greater omentum is then dissected off the right transverse colon.

Step 3: Division of the Ileocolic Pedicle.

After mobilization of the colon is achieved, the next step is to incise the mesentery. A unique feature of the right colon mesentery is the presence of large avascular windows within the mesentery. There is an avascular mesentery between the ileocolic artery and the right branch of the middle colic artery and between the ileocolic artery and the last ileal branch. The peritoneum over the avascular mesentery is skeletonized with a Bovie cautery, and then the ileocolic artery and vein are dissected to their origin at the base of the mesentery. Proximal and distal ties are placed on artery and vein and ligated twice. The avascular mesentery to the right branch of the middle colic artery is then incised by electrocautery. The right branch of the middle colic artery and vein is dissected, and then transected after proximal and distal ties are placed. The anatomy of the ileocolic artery is a constant structure, and in 90% of patients the right colic artery branches off from the ileocolic artery. Occasionally, the right colic artery is a separate branch off the superior mesenteric artery and is encountered when the mesentery is incised to the right branch of the middle colic artery.

Step 5: Postoperative Care.

Postoperatively, the patient is maintained on intravenous fluids and is started on ice chips on postoperative day 1 and on a clear diet on postoperative day 2. The diet is advanced to regular diet on passing flatus. The patient is usually discharged 4 to 6 days after the operation if the bowel functions and pain control have been achieved.16,17

Left Colon

Step 3: Colon Mobilization.

The dissection is started with the sigmoid colon being retracted to the right and the peritoneal reflection along the white line of Toldt proximal to the splenic flexure and distal to the pelvic inlet. The ureter should be identified as it crosses the iliac artery, and the operator should be careful that the ureter is not drawn up with the mesentery and accidentally divided.

Step 4: Margins Resection and Anastomosis.

The proximal and distal sites of colonic transection are identified and divided with a GIA (gastrointestinal anastomosis) stapling device. The left colon is now affixed by the mesocolon, and the peritoneum overlying the mesentery is scored to outline the path of transection. The left colic vessels should be doubly ligated with a high ligation to sample enough nodes adequately. The specimen is delivered once complete division of the vessels and mesentery are obtained. The specimen is opened off the field to identify the tumor and inspect the margins. The colonic re-anastomosis may be end-to-end, end-to-side, or side-to-side, depending on the caliber, blood supply, and mobility of the proximal and distal segments as well as on the surgeon’s preference. Complete mobilization of the proximal segment is required to ensure that the two segments of bowel are approximated without tension. The mesenteric defect is closed with interrupted 3-0 silk sutures. The fascia is then closed, and skin is closed either by staples or by subcutaneous sutures. The skin is left opened when there is gross contamination and closed via delayed primary closure.18

Sigmoid Colon

Sigmoid colon tumors, among the most common tumors, are treated by sigmoid colectomy. This involves division of the sigmoid and superior rectal vessels with anastomosis of the descending colon to the upper rectum. However, important structures such as the ureter, hypogastric nerve, and iliac vessels have to be identified during dissection of sigmoid tumors. Ureteral stent should be considered for surgeries involving large bulky tumor or in a previously radiated field. A review published by Bothwell and associates19 showed that experienced surgeons performed prophylactic ureteral catheter placement in 16.4% of their sigmoid and rectosigmoid colectomies. The risk of ureteral injury (1.1%) as a direct result of catheter insertion is small, but not insignificant. Prophylactic ureteral catheters do not ensure the prevention of transmural ureteral injuries, but may assist in their immediate recognition.19

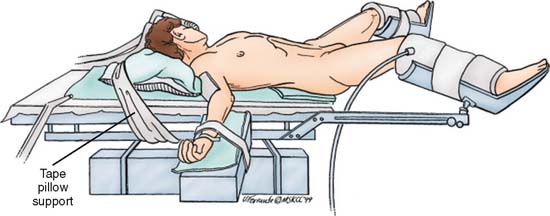

Step 1: Mobilization of Colon.

The patient is placed in the supine position with arms abducted on arm boards and legs in a low lithotomy position (Fig. 14-3). After abdominal exploration, the small bowel is packed into the upper abdomen, and the patient is placed in a slight Trendelenburg position. The rectosigmoid is retracted to the right, and the peritoneal attachments to the left of the sigmoid colon are incised along the avascular plane. The peritoneum is incised along the left side of the descending colon as far as the splenic flexure. Adhesions to the spleen are divided, and the splenic flexure is taken down. The colon mobilization extends proximally to the left transverse colon.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree