2 Presentation and Initial Evaluation of Colorectal Cancer

Presentation

In the United States, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer diagnosis and the second leading cause of cancer death.1 Because it is so prevalent, as early as 1980 the American Cancer Society issued guidelines for CRC screening in average-risk adults.2 As a result, recent trends in the incidence of and mortality from CRC reveal declining rates, partly because of effective screening and prevention through polypectomy.3 However, despite prospective randomized trials that have demonstrated decreased mortality rate with early detection of CRC,4 most adults in the United States do not receive regular age- and risk-appropriate screening. Poor screening participation has been attributed to a variety of factors, including lack of health insurance and lower socioeconomic status.5–7 However, even in the setting of universal health care, compliance with recommended screening remains low. A recent retrospective study from British Columbia, Canada, reported that out of 212 patients with CRC, less than 7% were diagnosed via a screening test, and only 15% of screeningeligible patients had been screened.8 Similarly, in the United States, nearly 85% of patients with CRC have symptoms from their tumors before a diagnosis is made.9 Therefore, it remains especially important to recognize the clinical signs and symptoms of CRC and to appropriately initiate workup when necessary.

Symptoms

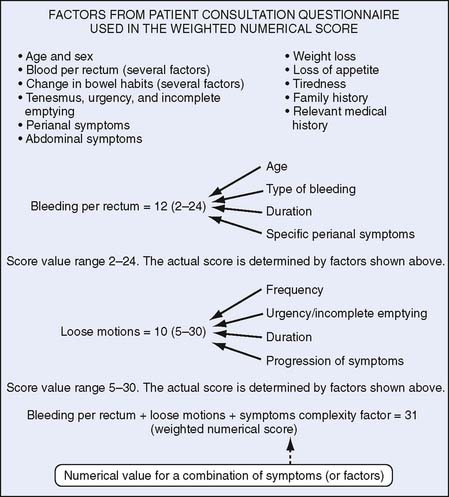

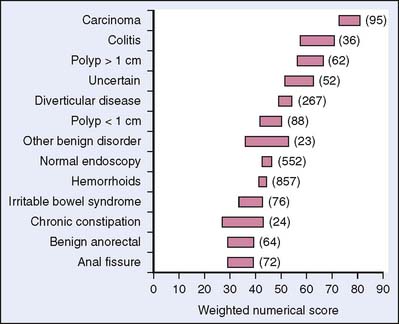

In a prospective study of 2268 patients in the United Kingdom with distal colonic symptoms, a questionnaire was developed to facilitate the prioritization of patients to be seen by a specialist. The questionnaire screened for primary symptoms and symptom complexes of CRC and was completed by the patients before seeing a specialist. A weighted numerical score was then derived from the questionnaire based on related symptoms (Fig. 2-1). The weighted numerical score is calculated by a computer based on a formula derived subjectively by weighting of symptoms and symptom complexes in relation to the likelihood of cancer outcome. The higher the numerical score, the greater are the odds that the patient has CRC, with scores higher than 70 associated with a 1 in 5 risk and scores lower than 40 associated with a risk of 1 in 967. Of the 2268 patients, 95 were found to have CRC, and the weighted numerical score was significantly higher for patients with cancer than for noncancer patients (mean 76.5 [95% confidence interval, CI, 72.2–80.9] compared with 44.5 [95% CI 43.6–45.4], P < .0001) (Fig. 2-2).10 As with classic teaching, symptoms of bleeding per rectum, change in bowel habits to loose movements, and increased frequency of defecation were associated with the highest relative risk ratios. Although a computer-generated score may serve as a surrogate for experience-based clinical suspicion, it also demonstrates that it is possible to identify at-risk patients based on symptoms alone.

Figure 2-1 Principle of the weighted numerical score.

(From Selvachandran SN, Hodder RJ, Ballal MS, et al: Prediction of colorectal cancer by patient consultation questionnaire and scoring system: a prospective study. Lancet 360:278–283, 2002.)

Figure 2-2 Disease outcome and 95% confidence interval of average weighted numerical score.

(From Selvachandran SN, Hodder RJ, Ballal MS, et al: Prediction of colorectal cancer by patient consultation questionnaire and scoring system: a prospective study. Lancet 360:278–283, 2002.)

Another study that supports identifying symptom “clustering” was published by Majumdar and associates.11 In classic teaching, the presentation of CRC may vary depending on the location of the tumor. Proximal colon cancers are more often occult and are more often associated with anemia, whereas distal cancers are more likely to demonstrate gross rectal bleeding or a change in stool caliber. A retrospective study of 194 consecutive patients with a known diagnosis of CRC identified distinct clustering of symptoms related to the location of the tumor.11 In this study, 83% of patients were diagnosed with CRC based on investigation of related symptoms; the remaining 17% were detected by accident. Fifty-eight percent had distal tumors, and 48% had proximal tumors. The most common symptoms were rectal bleeding (58%), abdominal pain (52%), and a change in bowel habits (52%). On univariate analysis, patients who presented with a combination of anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or fatigue were more likely to have a proximal CRC. Other symptoms such as diarrhea, mucus in stools, rectal pain, and tenesmus were associated with distal tumors. On multivariate analysis, independent predictors of a distal tumor included mild anemia, rectal bleeding, and constipation.

As the authors conclude, certain symptoms share common pathophysiology and therefore occur in clusters.11 For example, patients with proximal tumors often present with symptomatic anemia without gross rectal bleeding, having generalized weakness or fatigue. Unlike more distal tumors, which manifest as rectal bleeding, proximal tumors may grow subclinically until near obstruction, at which time patients present with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Another example is metastatic disease, which may manifest as right upper quadrant pain or constitutional symptoms, such as fevers, night sweats, and weight loss.

Signs

CRC is often difficult to establish based on physical examination alone. Infrequently, colon cancer may present as a palpable abdominal mass. In contrast, rectal cancer is often palpable on physical examination. In particular, several prognostic characteristics with regard to the primary rectal cancer have been identified. In a study of 769 patients with CRC who were undergoing preoperative radiation, the preoperative assessment of mobility of the tumor, the number of quadrants involved, as well as the distance of the tumor from the anal verge were identified in a multivariate analysis as being predictive of a curative resection.12 Patients with tumors that were mobile regardless of the number of quadrants involved had a 78% to 84% curative resection rate. Those with tumors that were partially fixed and involved one quadrant had a 56% curative resection rate, whereas those with tumors that were partially fixed and involved more than one quadrant had a 39% curative resection rate. Although distance from the anal verge did not have an impact on resection rates, the 5-year survival rate was 42% for patients with tumors less than 5 cm from the anal verge compared with 64% for those with tumors 10 to 15 cm from the anal verge.

In addition, anterior tumor location has been associated with a trend toward higher survival rates, although not statistically significant when compared with posteriorly located tumors.13 Additional signs of CRC usually are associated with advanced disease. Anemia from gastrointestinal bleeding generally is associated with iron deficiency and may classically manifest as pallor, brittle spooned nails, and glossitis. Patients with hypoalbuminemia may present with ascites or anasarca. Hepatomegaly, supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, and cachexia may be indicative of metastatic disease.

Duration of Symptoms

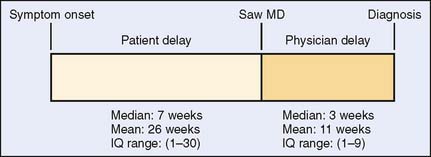

There are several challenges in identifying patients with CRC. As previously discussed, the signs and symptoms of the disease may be misinterpreted as benign disease. Both patients and physician are influenced not only by the presence or absence of symptoms, but also by the severity, chronicity, and progressive nature of the symptoms. In a study of 294 CRC patients, symptoms that were unusual, severe, or of short duration were more likely to be reported by patients.14 Majumdar and associates11 reported median symptom durations of 3 months before diagnosis. This finding has been corroborated by other studies, which report durations of 2 to 4 months.14,15 Symptoms such as obstruction or rectal bleeding had shorter duration, whereas more chronic symptoms such as weight loss had the longest duration (median 27 weeks). Moreover, patients and physicians contributed to delays in diagnosis11 (Fig. 2-3). The median duration of symptoms before a patient sought medical care was 7 weeks. The median time to diagnosis after presentation to medical care was 3 weeks, and most cancers were diagnosed within 1 month of presentation. The study found no relation between duration of symptoms and the stage of cancer. The lack of association between duration of symptoms and cancer stage is counterintuitive but has been reported by previous studies as well.15–17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree