3 Hereditary Colorectal Cancer and Polyp Syndromes

Introduction

Colorectal adenocarcinoma is a major human health problem. This malignancy affects 1 million individuals per year worldwide, causing 500,000 deaths annually.1 In the United States, each person has a 6% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer, and colorectal adenocarcinoma is the second leading cause of cancer-related death.

This chapter discusses the two well-described forms of hereditary colorectal cancer: hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Also, other syndromes caused by germline mutations that increase the risk of colorectal cancer are reviewed (Table 3-1).

Table 3-1 Inherited Disorders Causing Colorectal Cancer

| Inherited Condition | Genes Mutated |

|---|---|

| Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) | Mismatch repair (MMR) genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) |

| Muir-Torre syndrome | MMR (usually MSH2) |

| Attenuated HNPCC | MSH6 |

| Trimbath syndrome | MMR biallelic mutation |

| Turcot syndrome | MMR |

| Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) | APC |

| Attenuated FAP | APC 5′,3′ mutation |

| Crail syndrome | APC |

| MYH-associated polyposis (MAP) | MYH biallelic mutation |

| MYH-associated colon cancer | MYH monallelic mutation |

| I1307K mutation of APC gene | APC I1307K mutation |

| Juvenile polyposis | SMAD4, BMPR1A |

| Cowden syndrome | PTEN |

| Bannayan-Ruvalcaba-Riley syndrome | PTEN |

| Peutz-Jeghers syndrome | STK11/LKB1 |

Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) is a syndrome known by other appellations including Lynch syndrome and cancer family syndrome.2 More recently, this condition has been designated HNPCC, unlike FAP, in which colorectal cancer arises from colorectal adenomatous polyposis. In hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, colon malignancies usually occur from a single or a few adenomas—hence the term nonpolyposis.

Characteristics

HNPCC is an autosomal dominant condition caused by mutation of one of the mismatch repair (MMR) genes.3 These genes are responsible for maintaining the fidelity of DNA by correcting base-pair mismatches that occur during cell replication. HNPCC accounts for about 1% to 3% of all colorectal cancer. The lifetime risk of colorectal cancer in persons with an MMR gene mutation approaches 80%, and the mean age at diagnosis of colorectal cancer in this syndrome is 44 years old. However, a wide range of age at diagnosis is noted; patients not infrequently present with colorectal malignancy in the second or third decade of life. Most tumors in HNPCC (60% to 80%) are found in the right colon defined as proximal to the splenic flexure.4 Histologically, HNPCC is more likely to be poorly differentiated, abundant in extracellular mucin, and distinguished by a lymphoid (peritumoral lymphocytes) host response to the tumor.4 Some investigators report that patients with HNPCC have an improved 5-year survival rate, compared stage for stage with individuals with sporadic (noninherited) colorectal malignancy.

HNPCC patients and family members can develop a wide range of extracolonic malignancies.5 The highest risk for other tumors is that for endometrial cancer (40% to 70% lifetime risk). Also, these patients can have adenocarcinomas of the stomach, small bowel, biliary tract, or ovary; glioblastoma of the brain; and transitional cell carcinoma of the ureter, urethra, bladder, or renal pelvis. The lifetime risks for these cancers range between 2% and 13%. Also, lung, breast, hemopoietic, and prostate and larynx cancers have been reported in HNPCC kindreds, but most studies have not noted increased relative risks for these malignancies. Café-au-lait spots, sebaceous gland tumors, and keratoacanthomas (the latter two are stigmata of the Muir-Torre variant of HNPCC) are the only reported clinical signs in HNPCC patients.

In 1990, the International Collaborative Group (ICG) on Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer established research criteria for HNPCC6 (Box 3-1). Known as the Amsterdam I criteria, these guidelines are used for the clinical diagnosis of HNPCC. Some experts felt these standards were too stringent for clinical application, and alternative criteria (Amsterdam II criteria) were proposed7 (see Box 3-1).

Box 3-1 Amsterdam I and II Criteria for Diagnosis of Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC)

Amsterdam I Criteria

Genetics

Microsatellite instability (MSI) is an event noted in the colorectal cancer DNA of individuals with germline mismatch repair gene mutations but not in the patient’s adjacent normal colorectal mucosa. MSI is found in 90% of colon tumors of HNPCC patients diagnosed by Amsterdam I criteria.8 In comparison, MSI is noted in 15% to 20% of individuals with sporadic colorectal cancers. MSI is typified by expansion or contraction of short, repeated DNA sequences (microsatellites) due to insertion or deletion of repeated units. The revised Bethesda criteria are clinical indications for obtaining MSI testing on patients with colorectal cancer9 (Box 3-2).

Box 3-2 Revised Bethesda Guidelines for Microsatellite Instability Testing of Colorectal Tumors

Adapted from Umar A, Boland CR, Terdiman JP, et al: Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst 96:261–268, 2004.

* Colorectal, endometrial, stomach, small bowel, ovarian, pancreas, ureter and renal pelvis, biliary tract, and brain (usually glioblastoma) cancers, and sebaceous gland neoplasms (carcinomas adenomas) and keratoacanthomas

† MSI-H, microsatellite instability—high; tumors with changes in two or more of the five National Cancer Institute-recommended panels of microsatellite markers.

‡ Presence of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, Crohn-like lymphocytic reaction, mucinous/signet-ring differentiation, or medullary growth pattern.

Several genotype-phenotype correlations are known in HNPCC as follows: (1) Muir-Torre syndrome, a rare variant of HNPCC, is defined as the association of HNPCC with skin sebaceous gland neoplasms (adenomas, epithelioma, carcinomas) and/or keratoacanthomas.10 In Muir-Torre patients with identified germline alterations of the MMR genes, MSH2 mutations are most often found. (2) Those with mutation of the MSH6 gene have an “attenuated” form of HNPCC.11 MSH6 carriers have less risk for all HNPCC-related tumors (except for one) than patients with alterations of the MLH1 or MSH2 genes. In MSH6 carriers, the cumulative risk for colorectal cancer is lower than other MMR gene mutations—69% in males and 30% in females (80% in other MMR gene mutation carriers) at 70 years of age. However, endometrial cancer risk is higher (71%) in those with MSH6 mutations (40% in other MMR gene carries). (3) Homozygous mutations of the MMR genes, such as PMS2 and MLH1, result in pedigrees typified by cutaneous café-au-lait spots, early onset of colorectal neoplasia, oligopolyposis (5 to 100 adenomas of the colon), glioblastoma at young age, and lymphoma. This constellation of findings is known as Trimbath syndrome.12 (4) Turcot syndrome describes patients with HNPCC and a glioblastoma brain tumor as an extracolonic manifestation.

Screening

Recommendations for colorectal screening in HNPCC have been generated by consensus opinion.13 Without genetic testing, first-degree relatives of affected individuals are recommended to have a colonoscopy every 1 to 2 years, starting between 20 and 30 years of age and continuing annually after 40 years of age, or alternatively every 1 to 2 years, beginning at age 20 to 25 or 10 years younger than the age of the person with the earliest colorectal cancer diagnosis in the family—whichever comes first. (Individuals with germline mutations are recommended to have an annual colonoscopy.). Because of the associated risk for endometrial and ovarian cancer, annual screening in women beginning at age 25 to 35 is recommended with consideration of transvaginal ultrasound (with or without CA-125 testing) and endometrial biopsy. In families with a predilection for gastric or urologic tumors, upper endoscopy or urinalysis and urine cytology, respectively, should be included in the surveillance protocol.

When possible, genetic testing for HNPCC is recommended for screening first-degree relatives of HNPCC patients who are over age 18. Screening begins by testing an affected member of the family to identify the pedigree mutation. Microsatellite testing and/or immunohistochemistry testing is indicated for patients who meet the Revised Bethesda Criteria. Germline testing for mutations of MSH2, MLH1, and MSH6 is also commercially available. For details of genetic testing in HNPCC, see Chapter 4.

Treatment

Because of the high rate of metachronous colorectal cancer, subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis and postsurgical endoscopic rectal surveillance are recommended when colorectal cancer develops in the setting of HNPCC.14 There is no consensus regarding prophylactic surgery of the colon, uterus, and ovaries for MMR gene mutation carriers, but it should be considered on an individual patient basis.

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is an autosomal dominant syndrome caused by a germline mutation of the APC (adenomatous polyposis coli) gene.15 This disorder occurs in 1 in 10,000 to 14,000 live births, affects both sexes equally, and has worldwide distribution.

Characteristics

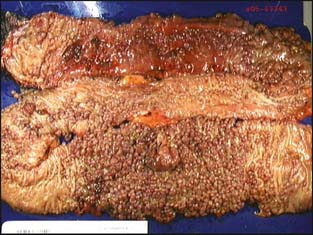

Patients with FAP characteristically develop colorectal adenomatous polyposis (i.e., ≥100 colorectal adenomas) in teenage years (Fig. 3-1). The mean age of polyposis development is 15. If colectomy is not performed, the lifetime risk of colorectal cancer is virtually 100% and occurs at an average age of 35 to 43 years.16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree