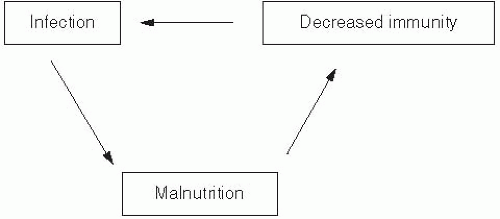

Malnutrition is a major determinant of morbidity and mortality for many major infectious diseases, particularly among young children in developing countries, who often suffer from multiple serial infections.

Diarrheal Disease

Diarrheal disease is the second leading cause of death in children younger than 5 years of age, causing an estimated 1.5 million deaths each year worldwide.

7 Malnutrition and associated immunodeficiency are important risk factors for diarrheal disease among infants and young children in developing countries. The main causes of diarrheal diseases among children in developing countries are rotavirus,

Escherichia coli, Shigella, Vibrio cholerae, Salmonella, and

Entamoeba histolytica. Children who are malnourished (low weight-for-age, low mid-upper-arm circumference) have an increased prevalence of diarrhea, which in turn can exacerbate their malnutrition, resulting in more severe disease and a higher mortality rate.

7,

8 and

9 Frequent episodes of diarrheal disease can also cause significant damage to the lining of the gut and disrupt normal gut flora colonization, which further exacerbates poor nutrition status and immune function.

Micronutrient deficiencies that have been described during diarrheal disease include deficits in vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin B

12, folate, copper, iron, magnesium, selenium, and zinc.

10 Several clinical trials show that supplementation with vitamin A

11,

12 and

13 or zinc

14,

15,

16,

17,

18 and

19 can reduce the morbidity and mortality of diarrheal disease in children, although the benefit of vitamin A appears to be limited to children who are vitamin A deficient or malnourished, or to children with shigellosis. The current recommendation from the World Health Organization (WHO) does not include vitamin A as part of treatment of diarrhea.

Lower Respiratory Infections

Acute respiratory infections (ARIs) are a major cause of morbidity and mortality among infants and children in developing countries. According to a 2009 WHO report, these infections account for an estimated 2 million deaths per year.

20 The main causes of acute lower respiratory infections in children are respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, parainfluenza virus, influenza virus,

Streptococcus pneumoniae, and

Haemophilus influenzae.

21 Zinc is essential for the growth and development of children, and randomized controlled trials have shown strong evidence that zinc supplementation reduces the incidence and prevalence of ARIs and pneumonia among children, especially in zinc-deficient populations.

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27 and

28 Vitamin A deficiency causes pathologic alterations in the mucosal epithelium of the respiratory tract, including keratinization and loss of ciliated cells, mucus, and goblet cells. Epidemiologic studies have

demonstrated that vitamin A deficiency is associated with lower respiratory infections,

11 although vitamin A supplementation appears to have little effect on reducing the incidence of either lower respiratory infections in children

29 or respiratory syncytial virus infection,

30,

31 unless measles infection occurs at the same time.

12 Some evidence is emerging on the benefits of selenium, though further studies are needed to confirm this nutrient’s role in the treatment of ARIs.

21

Measles

An estimated 278,358 cases of measles and 164,000 measles-related deaths were reported in 2008.

32,

33 This number reflects a decrease of 78% since the launch of the Measles Initiative in 2000; it is a vaccination campaign in high-risk countries jointly led by the American Red Cross, United Nations Foundation, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), UNICEF, and WHO. Deaths from measles are largely the result of an increased susceptibility to secondary bacterial and viral infections, and the underlying mechanism includes immune suppression related to malnutrition.

34 Although most people recover from measles, those with malnutrition or coinfections are at increased risk of complications.

35,

36,

37 and

38 In the classic early investigation of a measles outbreak in the Faroe Islands by Peter Panum and August Manicus in 1846, the most severe diarrheal disease and highest mortality were described among those patients with greatest poverty and poor diet.

39 In general, malnourished children have more severe disease and higher mortality.

40,

41 More persistent measles infection and viral shedding

37 have also been reported in malnourished children.

35A close synergism exists between measles and vitamin A deficiency. Low serum vitamin A levels are associated with higher mortality in acute, complicated measles infection.

42 Vitamin A supplementation for measles is one of the most important examples of the use of micronutrients as disease-targeted therapy. Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials show that such supplementation can reduce the mortality of measles by 50% or more, and high-dose vitamin A supplementation is now recommended as standard therapy for measles both in developing countries and in the United States.

11

Tuberculosis

Approximately 1.8 billion individuals—nearly onethird of the world’s population—are infected with

Mycobacterium tuberculosis; most of these cases involve latent infection. In 2008 alone, an estimated 9.4 million new cases of tuberculosis (TB) occurred worldwide.

43 Malnutrition (along with poverty, overcrowding, and underlying human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection) is a major risk factor for the progression of latent tuberculosis infection to active infection.

44 Nevertheless, tuberculosis control programs tend to focus their efforts on chemoprophylaxis and chemotherapy alone, rather than upon improvement of host nutritional status.

Cod-liver oil—a rich source of vitamins A and D—was used as treatment for tuberculosis for more than 100 years, prior to the development of antibiotics.

45 Although the association between malnutrition and tuberculosis is well known, few controlled clinical trials have been conducted to investigate whether improved nutrition might reduce the risk of developing active disease or improve the clinical outcome of tuberculosis. A recent Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials comparing any oral nutritional supplement with no nutritional intervention, placebo, or dietary advice only among people being treated for active TB showed effects of high-energy supplements or combinations of multiple micronutrients including zinc and vitamin A on weight gain, but overall little evidence of effect on other clinical outcomes of TB.

46 The role of nutrition and tuberculosis remains a major area of neglect, despite the promise that micronutrients have shown as therapy for other types of infections and the long record of the use of vitamins A and D for treatment of pulmonary and miliary tuberculosis in both Europe and the United States.

Malaria

In 2008, there were an estimated 247 million cases of malaria and approximately 1 million deaths from this infection worldwide; more than 85% of all malaria cases occurred in Africa.

47 Vector control and antimalarial drugs have been the traditional strategy against malaria, and little attention, until recently, has been paid to improving host nutritional status.

Low levels of vitamin A, zinc, iron, and folate have been shown to be responsible for a substantial proportion of malaria morbidity and mortality.

48,

49 Two separate randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials conducted in Papua New Guinea demonstrated that vitamin A supplementation or zinc supplementation can reduce malarial morbidity in preschool children by 30-50%.

50,

51 Iron-deficiency anemia is widespread among malaria-endemic regions, and iron supplementation is often a key component of relief efforts. A meta-analysis of iron supplementation in malaria endemic regions, however, showed a tendency toward higher parasite counts in individuals who received iron supplements.

52 In contrast, a

2011 Cochrane review reported that there was no increased risk of malaria with iron supplementation in areas that have regular malaria surveillance and where malaria treatment services were provided.

53 On this basis, it was recommended that iron supplementation should not be discontinued in areas that are malaria endemic.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

In 2009, there were an estimated 33.3 million persons infected with HIV worldwide, with 2.6 million new infections and 1.8 million deaths from this cause occurring in that year alone.

54 Currently, approximately half of the people living with HIV are women and 2.5 million are children younger than the age of 15. Malnutrition may affect the course of HIV infection through a variety of mechanisms, including compromising host immune function, diminishing response to therapies, and promoting comorbidities.

4 Wasting and malnutrition were routinely observed in AIDS patients in the early years of the HIV epidemic.

55,

56 With the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in the mid-1990s, however, many of the more severe nutritional problems associated with HIV infection declined in prevalence, particularly in resource-rich countries where patients had access to HAART. Given that most people with HIV infection live in resource-poor countries with limited access to HAART, HIV-related malnutrition remains of important concern on a global basis.

HIV wasting syndrome has been associated with increased opportunistic infections (OIs), lower CD4 counts, and hyperactivation of the immune system.

57,

58,

59 and

60 Weight loss of as little as 5% of total body weight is predictive of death.

61,

62 Prior to the introduction of HAART, specific micronutrient abnormalities were more common in HIV-positive than HIV-negative individuals.

63,

64 and

65 Low serum levels of many of these nutrients (particularly, vitamins A, B

6, and B

12, as well as zinc) were associated with more rapid disease progression,

66 increased mortality,

67 impaired neurologic function,

68 diminished lymphocyte response to mitogens,

64 and increased maternal-fetal transmission.

69 These micronutrients may be involved in the pathogenesis of HIV infection through their roles as antioxidants and in immune function.

Several clinical trials of multiple micronutrient supplementation in HIV-infected adults have been published.

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76 and

77 The earliest and largest of these— a trial among HIV infected pregnant women in Tanzania—showed that multivitamin supplementation (compared to placebo) had several beneficial outcomes in HIV-infected pregnant women, including greater increases in T-cell counts during and after pregnancy, better birth outcomes (reduced fetal deaths and low birth weight),

78 and improved weight gain during pregnancy.

79 Further follow-up of the same women over several years’ time demonstrated continued benefits of supplementation with multiple micronutrients in the form of higher T-cell counts, lower viral loads, slower HIV progression, and improved overall survival.

70 Additional analyses of these trial participants showed a beneficial effect of micronutrients on maternal wasting,

80 maternal and child hemoglobin status,

81 and maternal depression and quality of life.

82The other, more recent clinical trials showed mixed results. These trials were much smaller and were conducted in different geographic regions (Southeast Asia, Africa, United States) with differing population characteristics (including differing levels of micronutrient deficiency at baseline) and used different mixes and doses of multiple micronutrients, making it difficult to draw any generalizable conclusions. Some of these studies were conducted among pregnant women,

76 others involved people coinfected with TB,

73,

74 and only one took place in a population treated with antiretroviral therapy.

77 Currently, many people living with HIV in resource-poor countries are gaining access to antiretroviral therapy, so the effects of micronutrient supplementation on HIV outcomes need to be reassessed in light of this fact.

In terms of energy requirements, a 2003 WHO report recommended that energy requirements should be increased by approximately 10% to maintain body weight and physical activity in asymptomatic HIV-positive adults and growth in asymptomatic HIV-positive children.

83 For persons in the symptomatic stages of HIV and AIDS, WHO recommended that energy requirements increase by approximately 20-30% to maintain adult body weight; for children experiencing weight loss, the recommendation was that energy intake increase by 50-100% over normal requirements. For patients on HAART, however, resting energy expenditure and energy requirements appear to be more variable

84,

85,

86 and

87—an issue that requires further study.