Mouth and Salivary Gland Syndromes

Gingivitis, Stomatitis, and Dental Infections

Definitions

Inflammatory disease of the oral cavity should be diagnosed first in terms of the anatomic area involved, and then in terms of the probable etiology. Anatomic diagnoses commonly used include stomatitis (inflammation of the buccal mucosa), gingivitis (inflammation of the gums), gingivostomatitis, and glossitis (inflammation of the tongue). Inflammation of the lips is best called labiitis (Table 4.1).

Clinical Patterns

Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis

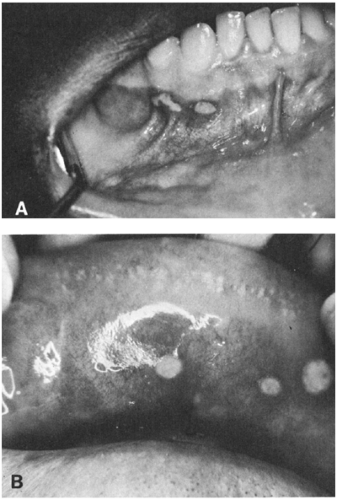

Called “canker sores” by laypersons, these lesions usually appear as a superficial red ring with a shallow mucosal ulceration covered by a gray membrane (Figure 4-1). They involve the wet, moveable mucosa—typically the buccal mucosa, occasionally the ventral surface of the tongue, and less commonly the lips or gums. These lesions do not involve the attached gingiva or hard palate. In the most severe form, the lesion extends into the submucosa and is called periadenitis aphthae. The cause of aphthous stomatitis remains uncertain, but investigations suggest several associations. First, aphthous ulcers are associated with poor cytotoxic T lymphocyte function and/or neutropenia.1 Second, some patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis have poor regulation of the inflammatory cytokine cascade.2

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis in association with fever may be a clue to a syndrome of unknown cause called PFAPA (periodic fever, adenitis, pharyngitis, and aphthous stomatitis) (see Chapter 10).3 Children with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection can also be afflicted with refractory aphthous ulcers.4 Children with cyclic neutropenia

or chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) may also present with recurrent aphthous ulcers.5,6 Interestingly, most carriers of X-linked CGD have recurrent aphthous ulcers as well.7 Rarely, recurrent aphthous stomatitis is a clue to the diagnosis of Behçet’s disease, discussed below.

or chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) may also present with recurrent aphthous ulcers.5,6 Interestingly, most carriers of X-linked CGD have recurrent aphthous ulcers as well.7 Rarely, recurrent aphthous stomatitis is a clue to the diagnosis of Behçet’s disease, discussed below.

TABLE 4-1. MOUTH AND DENTAL INFLAMMATORY DIESEASE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

FIGURE 4-1 Aphthous stomatitis. (A) Lesions of mucosa below the gingiva. (Photo from Dr. John Duffy) (B) Lesions of the upper lip. (Photo from Dr. Edward Graykowski) |

Whether infectious agents sometimes cause aphthous ulcers is not known. Most attempts at associating infectious agents with this disease have been fruitless. Physical and psychological stress precipitates attacks in susceptible people, probably by affecting the function of the immune system.8

Aphthous ulcers resolve without treatment. Pain relief may be afforded by treatment with over-the-counter products. Frequent or severe ulceration may respond to topical application of nonaqueous steroid sprays intended for intranasal use. The mucosa is simply wiped dry, and the ulcer is sprayed. This may be done twice a day and usually results in rapid resolution. Some patients with recurrent aphthous ulceration respond to a toothpaste that does not contain sodium lauryl sulfate.9 Severe, refractory, or widespread aphthous ulceration such as that seen in HIV disease is occasionally treated with thalidomide.10 These patients should be in the care of an infectious diseases specialist.

Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis

Formerly called “trench mouth” (because it was common in soldiers in the trenches in WWII) or “Vincent’s angina,” necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) occurs at the gingival papillae between the teeth (Fig. 4-2, panel A).11 The diagnostic triad of NUG is pain, interdental ulceration, and bleeding,

and patients may also develop fetid breath and form a pseudomembrane.12 NUG has been attributed to a synergistic infection with spirochetes, fusobacteria, or, in childhood especially, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans.13 All of these organisms are normal inhabitants of the mouth, so a causal association has been hard to prove. Molecular techniques have shown, however, that the spirochetes found in these lesions contain pathogen-specific determinants and that patients with NUG often have a serological response to these spirochetes, which would not be expected if they were not pathogenic.14

and patients may also develop fetid breath and form a pseudomembrane.12 NUG has been attributed to a synergistic infection with spirochetes, fusobacteria, or, in childhood especially, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans.13 All of these organisms are normal inhabitants of the mouth, so a causal association has been hard to prove. Molecular techniques have shown, however, that the spirochetes found in these lesions contain pathogen-specific determinants and that patients with NUG often have a serological response to these spirochetes, which would not be expected if they were not pathogenic.14

Most cases occur in adults, but the disease can be seen in adolescents or younger children. Although it occurs with higher frequency in people who live in crowded settings, it is not thought to be contagious.15 Transmission by fomites or vectors has never been documented.16 The lay diagnosis of “trench mouth” in a young child is likely to refer to herpes simplex gingivostomatitis.

In adults, risk factors for NUG include poor oral hygiene, unusual emotional stress, inadequate sleep, Caucasian race, age 18–21 years, and recent illness.12 Severe juvenile NUG should raise the question of a defect in neutrophil locomotion. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients also are at higher risk of NUG, and occasionally acute NUG is the presenting sign of HIV infection, at least in young adults.17 In children with cancer, especially those with neutropenia, poor nutrition, and marginal oral hygiene, acute NUG can result in loss of teeth.18

Penicillin usually results in dramatic improvement.19 Interestingly, the effectiveness of the antiparasitic drug metronidazole against anaerobes was discovered when it was used for trichomonal vaginitis and produced dramatic improvement in a patient with NUG.

Gum Abscess

This abscess may be seen before the eruption of teeth.19 It is usually caused by normal mouth flora, but a case caused by the gonococcus has been reported.20 It is also called a parulis or “gum boil.”

Gingivitis or cystic, pink, nontender gingival masses about 1 cm in diameter have been described in patients with occult pneumococcal bacteremia (see Chapter 10).21

Glossitis

A swollen, painful tongue can be caused by acute bacterial infection of any type but in children is most likely to be due to Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal, staphylococcal, or Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) infection.22 The latter has become exceedingly rare since the institution of an effective H. flu type b vaccine. In patients with HIV infection or other severe immune suppression, herpes simplex virus can cause a syndrome known as herpetic geometric glossitis.23 This clinical syndrome is marked by painful tongue fissures or furrows, and responds to intravenous acyclovir.

Glossitis has also been associated with systemic diseases, especially vitamin B12 deficiency and pernicious anemia.24 Geometric tongue is a noninfectious condition seen in fair numbers of otherwise well children. The pattern on the tongue changes with time, and is not symptomatic. Coated tongue is a condition that can be seen in normal children during the course of acute infection with respiratory viruses. The cause of coated tongue is not well delineated. It goes away with resolution of the respiratory infection. The exception is “coated tongue” in patients with immune suppression25—this clinical scenario is likely to be a manifestation of thrush and should be treated (discussed later). Coated tongue is also a common finding in typhoid fever.

Pulpitis and Periapical Abscess

Complications of Dental Infections

A periapical abscess of a mandibular tooth can drain to the outside of the lower gum as a sinus tract (parulis) or can spread medially to produce a neck space infection.27 An abscess of a maxillary tooth can spread medially to form a submucosal abscess of the hard palate, or laterally to produce facial cellulitis.27 Chronic proliferative periostitis (Garre’s osteomyelitis) usually is a reaction to adjacent dental infection. It produces an “onion skin” appearance of the mandible on x-ray, and resembles Caffey’s disease. Treatment of the dental problem is indicated, but systemic antibiotics are usually not required.27

Uvulitis

A red or swollen uvula may have several causes, discussed in the section on pharyngitis (Chapter 2).

Possible Etiologies

Herpes Simplex

This virus is the usual cause of acute gingivostomatitis in children. The primary infection typically occurs in the first 6 years of life. The illness is often associated with fever. There is often slight bleeding when the gums or buccal mucosa are touched. Glossitis may be present, with superficial circular ulceration of the tongue covered with a thin layer of white or gray exudate (see Fig. 2-7). Carefully moving the buccal mucosa out of the way with a tongue depressor will usually reveal ulcers on the gingivae. Lip involvement is not common in the first infection. The incubation period is about 7 days, with a range of 3–9 days.28 The patient usually improves in 3–5 days and has recovered by 14 days. Outbreaks of acute gingivostomatitis caused by this virus have been observed in young children in nurseries or orphanages.28

Reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection can also cause recurrent stomatitis, gingivostomatitis, or labiitis. Recurrences are usually extraoral, on or near the lips (see Fig. 11-9), unlike the primary infection, which is usually intraoral. The severity of recurrent illness is usually much less than that of the first episode. However, occasionally there is a recurrence of severe stomatitis with fever and mucosal bleeding. HSV is the most common trigger of erythema multiforme (EM) in children, in some cases leading to recurrent episodes of EM.29,30 Recurrent labiitis or stomatitis caused by HSV can be precipitated by another illness, such as pneumococcal pneumonia, or meningococcal or H. influenzae meningitis. Occasionally, the labiitis or stomatitis precedes signs of the precipitating disease, so the child should be examined carefully for another disease if some clinical findings seem atypical or overly severe to be explained by herpetic stomatitis alone.

As mentioned above, HSV can also cause herpetic geometric glossitis in patients with immune deficiency states. It has been reported in one child after cardiac transplant, and in one child with acute myelogenous leukemia in addition to being seen in children with AIDS.23

HSV stomatitis may present a difficult diagnostic problem when a febrile child is seen early in the illness and the stomatitis has not yet appeared. When stomatitis occurs a day or two later, it is difficult to be certain that the gingivostomatitis does not represent a secondary reactivation of a latent infection by fever of some other cause. In one study, the fever sometimes preceded stomatitis by a day or two, and HSV was believed to be the cause of both the fever and of the later stomatitis.31 However, in experimental infections in adults with other viruses, HSV was frequently recovered before the experimental illness, suggesting that HSV often is a coincidental isolate associated with another infectious process.32

Virus excretion in patients with recurrent herpes labialis is greater during episodes of the common cold or after oral trauma.33 Patients with prodromal symptoms that lead them to expect a recurrence often have increased excretion of the virus in the absence of visible lesions.

Coxsackievirus

Stomatitis somewhat resembling aphthous stomatitis can be caused by Coxsackievirus A. However, the lesions of coxsackievirus infection are usually smaller and more erythematous and tend to be more predominantly located in the posterior oropharynx. The illness is called hand-foot-and-mouth syndrome when it is associated with a papular rash on the palms and soles, as described in Chapter 11. The disease sometimes presents with stomatitis alone.

Behçet’s Syndrome

Aphthous stomatitis rarely is an indication that a child has Behçet syndrome.34,35 This syndrome has been observed in children as young as 2 months of age and eventually may include arthritis, erythema nodosum, sterile cellulitis, perineal or genital ulcerations, and involvement of the eye, gastrointestinal tract, or neurologic system.35 Corticosteroid therapy usually provides symptomatic relief.36 Children with suspected or confirmed Behçet’s syndrome should be managed in concert with a pediatric rheumatologist.

Candida albicans

Stomatitis produced by this yeast typically occurs in young infants and often involves the tongue as well as the buccal mucosa. When yeasts are found to be a cause of stomatitis after about 6 months of age, a defect of cell-mediated immunity should be suspected.37 Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis is discussed in Chapter 23.

Syphilis

The chancre of primary syphilis is a rare cause of an ulcer on the lip, buccal mucosa, or palate. Regional lymphadenopathy is usually present.38

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

Severe gingivostomatitis is also rarely caused by Stevens-Johnson syndrome (discussed in Chapter 11). Typically, there is involvement of at least one other mucous membrane such as the conjunctiva or the urethra. This syndrome probably represents a hypersensitivity reaction. It is most commonly drug induced, but is occasionally secondary to an infectious process.39

Other Causes

Neutropenia from any cause should be excluded by a white blood count and differential study when ulcerative or necrotic lesions are seen on the gums.11 Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a rare cause of necrotizing gingivitis.40 Infectious mononucleosis is rarely associated with gingivitis or stomatitis.11

Trauma of the buccal mucosa or the gums can produce lesions resembling the ulcerations of stomatitis (Fig. 4-2). It is commonly secondary to chewing, operative procedures, or suctioning. Lichen planus can produce lesions in the buccal mucosa resembling those of aphthous stomatitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree