Abstract

Many women with breast cancer are menopausal at the time of their cancer diagnosis, and a significant number will enter menopause during treatment. Achievement of adequate control of menopausal symptoms has a meaningful impact on quality of life for breast cancer survivors. Although hormone therapy has proved efficacious in the management of various menopausal conditions, its use in women with a history of breast cancer remains controversial due to a dearth of safety data. This is true even of topical estrogens, which are typically used for vulvovaginal symptoms, given that systemic absorption of unclear significance has been demonstrated in studies. Alternative therapies, such as antidepressants, have proved particularly helpful in the management of vasomotor symptoms, especially considering that comorbid depression is common in this patient population. To counteract the increased risk of bone density loss and fracture, bisphosphonates have emerged as favored treatment, with data suggesting that these agents may also reduce risk of disease recurrence. With advances in diagnosis and treatment, an increasing percentage of women are becoming breast cancer survivors, and comprehensive care of this patient population requires effective management of menopausal symptoms and related disease states.

Keywords

breast cancer, menopause, hormonal replacement therapy, hot flashes, depression, osteoporosis

American women enter menopause at the average age of 51 years and spend one-third of their lives after menopause. More than 40 million women are now in or past menopause, and another 20 million will enter menopause over the next decade. With advances in oncologic diagnosis and treatment, breast cancer survivors constitute a growing proportion of these women. Also, treatment for breast cancer can speed the onset of menopause and increase the severity of menopausal symptoms.

This chapter explores menopause and discusses management of menopausal symptoms in breast cancer patients. The safety of hormone therapy (HT) for treatment of vasomotor and vulvovaginal symptoms in breast cancer survivors is explored, as are alternative treatments. Finally, menopause-related depression, osteoporosis, and cardiovascular disease are discussed with special consideration of the needs of breast cancer survivors.

What Is the Experience of Menopause in Women With Breast Cancer?

In the United States, more than 240,000 women are diagnosed with breast cancer annually. Approximately 25% are premenopausal at the time of diagnosis, and most of these women will lose ovarian function earlier than they would have otherwise, in many cases during chemotherapy. In premenopausal women with localized breast cancer, older age and more gonadotoxic chemotherapy are associated with a higher risk for amenorrhea 1 year after treatment. Only 30% of women diagnosed with breast cancer between 40 to 49 years old resume menstruation after receipt of standard adjuvant chemotherapy, although regimens that do not contain alkylating agents may be less likely to induce menopause. The risks of amenorrhea and associated menopausal symptoms with newer chemotherapy regimens requires further study because these can influence patient perceptions of the cost-to-benefit ratio of specific cancer treatments (thereby better informing decision-making).

The most widely acknowledged symptom of menopause is the hot flash, occurring in about 75% of all menopausal women. There is increasing evidence that hot flashes are a physiologic response to a change in the hypothalamic set point. During menopause, decreases in gonadal hormones appear to cause fluctuations in levels of norepinephrine and serotonin that, in turn, alter thermoregulation. In women without breast cancer, hot flash frequency and severity may be worsened by obesity, smoking, and stress. Hot weather, confining spaces, and ingestion of caffeine, alcohol, or spicy foods are acute triggers for some women.

Hot flashes can be objectively measured as diminished skin resistance. Duration ranges from 30 seconds to several minutes, and frequency and severity can vary substantially. Some women also experience palpitations and feelings of anxiety.

Most women remain symptomatic for more than a year. There is wide variability in the distress associated with hot flashes, with some women reporting hot flashes that disrupt sleep and adversely affect quality of life. For breast cancer survivors, hot flashes tend to be more frequent, more severe, and more persistent than in age-matched controls. The menopausal transition may last only weeks to months as chemotherapy and/or oophorectomy can cause estrogen levels to plummet, triggering the abrupt onset of vasomotor symptoms. Both tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors can incite or exacerbate hot flashes, and in one report, 20% of women discontinued or considered discontinuing adjuvant antiestrogen therapy because of intolerable side effects. As in all menopausal women, hot flashes and night sweats in breast cancer survivors are associated with poor quality sleep and increased fatigue.

Vulvovaginal symptoms usually begin 3 to 5 years after natural menopause but may occur within months of primary treatment for breast cancer. As estrogen levels decline, the vulva loses most of its collagen, adipose tissue, and water-retaining ability, becoming flattened and thin. The vagina shortens and narrows, and the vaginal walls become thinner, less elastic, more friable, and less able to produce lubricating secretions during intercourse. Vaginal pH becomes more alkaline, predisposing to colonization with urogenital pathogens. Symptoms include vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, vaginal bleeding, increased vaginal infections, urinary incontinence, and urinary tract infections. As potent suppressors of estrogen synthesis, aromatase inhibitors are associated with a high rate of urogenital symptoms. By contrast, tamoxifen may have estrogenic effects on the vagina, similar to the estrogenic effect it exerts on the uterus and bones.

Is Hormone Therapy an Option for Women With Breast Cancer?

Estrogen effectively controls hot flashes in perimenopausal women. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of HT demonstrate a significant reduction in symptoms compared with placebo (75% vs. 57%). Duration of therapy usually ranges from 1 to 3 years. In women with an intact uterus, a progestin is routinely added to curtail increasing endometrial cancer risk.

Listed among the absolute contraindications to estrogen use is a personal history of breast cancer. Although a 2001 systematic review suggested that HT does not increase the risk of recurrence in breast cancer survivors, the Hormonal Replacement Therapy after Breast Cancer Diagnosis—Is it Safe? (HABITS) trial did support the concept that HT was detrimental in survivors. This study recruited women with a history of up to stage II breast cancer and menopausal symptoms of sufficient severity to require treatment. Subjects received either 2 years of HT or nonhormonal, symptomatic treatment, with a primary end point of development of new breast cancers. The HT regimen was directed by local practice. After a safety analysis in 2003, the HABITS trial was terminated early, at which time follow-up data were available for 345 women, with a median follow-up of 2.1 years. New breast cancer events were reported in 26 women in the HT group compared with only seven in the non-HT group (relative hazard 3.3, confidence interval [CI] 1.5–7.4). Subgroup analyses for hormone receptor status, tamoxifen use, and prior HT use did not change the results.

In contrast, the Stockholm Randomized Trial reported that HT did not increase risk of breast cancer recurrence. This study enrolled women with a history of primary operable breast cancer and randomized them to either 5 years of standardized HT or no HT. After early termination related to safety concerns and poor accrual, new breast cancers were reported in 11 of 188 women in the HT group compared with 13 of 190 in the control group over a median follow-up of 4.1 years (hazard ratio [HR] 0.82, CI 0.35–1.9).

Differences in study design and between the study populations offer a partial explanation for these discrepancies. HABITS enrolled a higher proportion of lymph node–positive patients and fewer patients taking tamoxifen. It is important to note that HT may be both less dangerous and less effective at controlling vasomotor symptoms in women concomitantly taking selective estrogen receptor modulators, which may saturate the estrogen receptor. The Stockholm trial limited the use of continuous combined HT, which was hypothesized to stimulate breast cell proliferation, and it favored cyclic therapy, which was hypothesized to downregulate growth factors. This is consistent with findings from both the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) and the Million Women Study (a prospective cohort study of HT and incident invasive breast cancer), in which progestin-containing regimens were associated with a higher risk of breast cancer ( Table 82.1 ).

| Hormone | Risk |

|---|---|

| Estrogen alone | Lower risk of breast cancer compared with placebo in a large prospective, randomized trial of hysterectomized postmenopausal women but failed to achieve statistical significance |

| Estrogen plus progestin | Higher risk of breast cancer compared with placebo in a large prospective, randomized trial of postmenopausal women |

| Megestrol acetate | Safety in breast cancer unknown |

| Tibolone | Increased risk of breast cancer compared with never use of hormone therapy in one large observational trial of postmenopausal women |

| No recurrence at 1 year in a small prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of women with early breast cancer | |

| Soy phytoestrogens | Safety in breast cancer unknown |

An updated review of HT in breast cancer survivors included the HABITS trial, but data from the Stockholm trial were not available. There was no increased risk of breast cancer recurrence for all studies combined, but there was significant heterogeneity. The pooled relative risk for observational studies was 0.64 (CI 0.50–0.82) compared with 3.41 (CI 1.59–7.33) for randomized trials. The authors concluded that given limitations in the observational studies, only randomized trials would provide a reliable estimate of risk.

On the basis of current knowledge of the risks and benefits of HT, its use in breast cancer survivors remains questionable, and HT should be considered only for refractory and severe symptoms. If it is prescribed to a breast cancer survivor, HT should be used only at the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration possible. Informed consent is essential, and women need to be counseled on the lack of safety data.

Alternatives to Estrogen-Based Therapy for Management of Vasomotor Symptoms

Antidepressants

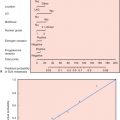

In the 1990s, both SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor) and SNRI (serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor) antidepressants were anecdotally noted to decrease hot flashes. These observations were independently seen with venlafaxine, paroxetine, fluoxetine, and sertraline, leading to the conduct of four trials ( Table 82.2 ).

| Agent | Recommended Target Dose | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Venlafaxine | 75 mg/day | Acute toxicity (nausea/vomiting) and withdrawal require careful dose escalation and tapering |

| Desvenlafaxine | 150 mg/day | Similar results as seen with other listed antidepressants |

| Paroxetine | 7.5 mg/day | Only FDA-approved agent for treatment of hot flashes; should be avoided in patients taking tamoxifen due to CYP2D6 blockade |

| Citalopram | 20 mg/day | Appropriate first-line agent for most patients |

| Escitalopram | 20 mg/day | Appropriate first-line agent for most patients |

| Gabapentin | 900 mg/day | Can be particularly helpful for women with predominantly nighttime symptoms |

| Pregabalin | 300 mg/day | More expensive and less well studied than gabapentin |

The first of these studies to be published was a randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluating three doses of venlafaxine and reported significant reduction in hot flashes among patients receiving this SNRI. The study supported a starting dose of 37.5 mg daily for a week, with subsequent increase to a target dose of 75 mg daily. An editorial accompanying this article acknowledged that this approach appeared to be helpful for hot flashes in breast cancer survivors but questioned whether it would be beneficial in patients without a history of breast cancer.

After the publication of this initial study, three additional randomized, placebo-controlled trials evaluating paroxetine, citalopram, and escitalopram were conducted; results indicated that these antidepressants were similarly helpful for decreasing hot flashes in women with breast cancer. Studies of fluoxetine and sertraline suggested comparatively limited efficacy of these particular SSRIs for hot flashes in this setting.

Subsequent studies have been performed to assess the efficacy of both SNRIs and SSRIs as treatment for hot flashes in women without a history of breast cancer, with results providing further support for use of these agents. A pooled analysis considered the impact of breast cancer history and tamoxifen exposure on the effectiveness of antidepressants; it reported that these nonestrogenic therapies were helpful in reducing hot flashes, irrespective of etiology.

None of the preceding medications were initially developed for treating hot flashes. Nonetheless, in 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration approved paroxetine for the treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. A recent review addressed the practical approach to use of these antidepressants, concluding that paroxetine, citalopram, and escitalopram are reasonable first-line options. Currently, paroxetine and citalopram are most cost-effective. Importantly, paroxetine should be avoided in combination with tamoxifen because paroxetine may inhibit cytochrome P450 CYP2D6, which metabolizes tamoxifen into endoxifen, and endoxifen is thought to confer much of the therapeutic benefit of the drug.

Gabapentinoids

Gabapentin and pregabalin reduce hot flashes to a similar degree as the newer antidepressant agents, irrespective of breast cancer history. A randomized, crossover, clinical trial that evaluated patient preferences between these agents found that patients preferred venlafaxine over gabapentin by a 2 : 1 margin, despite similar relief of vasomotor symptoms with the two agents. When switching from an antidepressant to gabapentin, it is recommended to continue the antidepressant for an overlap period of a couple weeks because abrupt discontinuation of the antidepressant is associated with increased side effects. These side effects likely reflect withdrawal symptoms, as opposed to gabapentin toxicity. Combination therapy with these agents does not confer a benefit in terms of hot flash reduction. When used for this purpose, the recommended target dose is 900 mg for gabapentin and 300 mg for pregabalin.

Clonidine

This centrally acting alpha-adrenergic agonist, used for management of hypertension, is associated with dry mouth, insomnia, constipation, and drowsiness. In a crossover trial, 116 women receiving tamoxifen for breast cancer and experiencing at least seven hot flashes per week received transdermal clonidine (equivalent to 0.1 mg orally) or placebo for 4 weeks. Those taking clonidine reported a 20% reduction in hot flash frequency compared with placebo. In a second trial, 194 women taking tamoxifen for breast cancer received oral clonidine 0.1 mg/day or placebo for 8 weeks. Women taking clonidine reported a 37% decrease in hot flash frequency at 4 weeks compared with 20% for placebo. At 8 weeks, there was a 38% reduction in frequency with clonidine compared with 24% for placebo. This drug is not often used for treating hot flashes because of the availability of alternative agents that are more efficacious and better tolerated.

Progesterone Analogs

In a crossover trial, 97 women with history of breast cancer and 66 men with prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy received either megestrol acetate 20 mg twice daily or placebo for 4 weeks. The megestrol group experienced an 85% reduction in hot flash frequency compared with 21% for placebo. In this study, 71% of the megestrol group experienced a 50% decrease in hot flash frequency compared with only 24% for placebo. There was a significant carryover effect from megestrol to placebo, and data could not be interpreted for the second treatment period. Vaginal bleeding was reported in 31% of women after withdrawal of megestrol. At 3 years of follow-up, 18 women were still using megestrol, and five experienced abnormal vaginal bleeding. Medroxyprogesterone acetate can be administered as a single intramuscular shot with about a 50-day half-life and decreases hot flashes to a similar degree as megestrol acetate. This provides a convenient dosing option, which can relieve hot flashes for months.

The long-term safety of progesterone analogs has not been evaluated in breast cancer survivors. Although the results from the WHI and Million Women Study suggest that progestins carry a higher risk for breast cancer when combined with estrogens, the implications of their use in isolation are unknown. Both megestrol acetate and medroxyprogesterone have been used in the past for treatment of metastatic breast cancer at higher doses; however, it is important to acknowledge and discuss with patients that the impact of this therapy on breast cancer prognosis is uncertain.

Complementary and Alternative Methods

Even before publication of WHI data, there was significant interest in complementary and alternative therapies for treatment of vasomotor symptoms, with 22% of menopausal women in one study reporting their use. Women with breast cancer are no exception. In a survey of women with recently diagnosed early-stage breast cancer, 28% reported new use of alternative therapies.

Vitamin E at a dose of 800 IU daily appears to have a marginal effect on hot flash frequency, with a reduction of less than one hot flash daily compared with placebo. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials found no data to support the effectiveness of red clover. Studies of black cohosh produced conflicting results. A systematic review of black cohosh in cancer patients included four studies in women with breast cancer. The authors concluded that in light of conflicting results and significant methodologic flaws, black cohosh does not appear to be effective. Soy phytoestrogens have also garnered considerable interest, but a review of 30 controlled trials concluded that there was no evidence to support their use for vasomotor symptoms of menopause.

A review of exercise for management of vasomotor symptoms could draw no conclusions because of a lack of trials. Other behavioral interventions, such as paced respirations and comprehensive support programs, have been shown to reduce symptoms but may be difficult to replicate outside of research settings. Newer studies have supported that hypnosis can reduce hot flashes, but this approach is not readily available to most patients.

Acupuncture has not been established as a means to decrease hot flashes, despite multiple attempts to address this subject. Pilot trial reports and a small double-blinded randomized trial support that stellate ganglion blocks can be helpful for treating hot flashes, although this approach is not commonly used in practice. There are also pilot data to support that oxybutynin, an agent commonly used for the treatment of urinary incontinence, can alleviate hot flashes, although no double-blinded placebo-controlled trials have been published to demonstrate success with this approach.

Are Topical Estrogens an Option for Women With Breast Cancer?

Oral and transdermal HT are no longer indicated for treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy in the absence of vasomotor symptoms. Vaginal estrogens are appealing because they are perceived to cause little systemic absorption. A review of intravaginal estrogens across 19 randomized trials concluded that creams, tablets, and rings were all effective. In this review, creams were most commonly associated with systemic absorption, whereas rings had the lowest absorption. A progestin was recommended for women with an intact uterus using creams at a dose greater than 0.5 mg estradiol daily. The ring had the highest acceptability, followed by tablets. Limitations of this review include short duration of treatment, small numbers of participants, exclusion of women with breast cancer, and heterogeneity in pooled results. Only seven trials were placebo controlled. Newer data support that all vaginal estrogen products are systemically absorbed to varying degrees. Safety data for vaginal estrogens in women with a history of breast cancer are sparse. A cohort study of 69 women previously treated for breast cancer (including those with estrogen receptor–positive tumors) who used low-dose topical estrogens for 1 year had no increased risk of recurrence, but the study was underpowered to detect such differences.

A prospective study of six women taking aromatase inhibitors for early-stage breast cancer showed a significant rise in serum estradiol after 2 weeks of daily therapy with vaginal estradiol 25-µg tablets for severe atrophic vaginitis. After 2 weeks, when dosing decreased to twice-weekly (as recommended by the manufacturer), estradiol levels dropped to pretreatment levels in only two of the six women. Given that effectiveness of aromatase inhibitor therapy relies on suppression of estrogen stimulation, it is reasonable to conclude that vaginal estrogens should not be used with aromatase inhibitors.

Alternatives to Topical Estrogens for Vulvovaginal Atrophy

Continued sexual activity, with its increase in blood flow, is thought to help maintain vaginal tissues. Water-based lubricants can decrease discomfort during intercourse. Women should avoid products such as detergents that may cause contact dermatitis. Polycarbophil-based moisturizers are hydrophilic polymers that bind vaginal epithelial cells and release fluid until sloughed. Such products induce epithelial cell maturation and restore normal pH and were shown to be as effective as vaginal estrogen in a randomized trial. In a randomized, double-blind, crossover study of 45 breast cancer patients, those using a polycarbophil product reported that symptoms of vaginal dryness decreased by 64% and dyspareunia by 60% after 4 weeks. Relief was comparable to a moisturizing placebo, which was not inert.

Data support that dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) decreases vaginal dryness and reduces sexual activity–associated discomfort without causing increased systemic estrogen levels in women with vaginal dryness who do not have breast cancer. In women with a history of cancer, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, supported that DHEA is safe and helpful in women with vaginal dryness and/or dyspareunia. Additional work in this area is needed.

Depression

Evaluation for and treatment of depression are important components for the comprehensive care of the woman with breast cancer ( Box 82.1 ). The prevalence of depression is as high as 50% in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Risk factors include difficulty coping with a cancer diagnosis, difficulty tolerating cancer treatments, work and family issues, sexual dysfunction, and a history of depression. The menopausal transition may contribute to these mood symptoms as well. Hot flashes and night sweats can cause sleep disturbances in both healthy women and breast cancer patients. Research suggests that the role of sleep disturbance in psychological distress is significant, but in both groups of women, it does not fully explain the effect of menopause on mood.

Prevalence as high as 50%

Risk factors

Difficulty coping with cancer diagnosis

Difficulty tolerating cancer treatments

Work and family issues

Sexual dysfunction

Menopause also associated with increased risk of depression

Hot flashes and night sweats

Other factors may also play a role

Screening for depression; positive response should prompt formal evaluation

Treatment: antidepressants, although women may be reluctant to take additional drugs, and some agents may interfere with tamoxifen therapy

Counseling

Although there are many screening questionnaires for depression, the following two Patient Health Questionnaire—2 (PHQ-2) questions may be sufficient for survivors:

- 1.

Over the past 2 weeks, have you felt down, depressed or hopeless?

- 2.

Over the past 2 weeks, have you felt little interest or pleasure in doing things?

The response options for these two questions are “Not at all” (scored 0), “Several days” (scored 1), “More than half the days” (scored 2), and “Nearly every day” (scored 3). A total score of 3 or greater for these two items warrants a formal evaluation for depression ( http://www.cqaimh.org/pdf/tool_phq2.pdf ).

Treatment of depression in a menopausal breast cancer survivor should be based on the history of any previous psychological disorders and medications used, as well as knowledge of the patient’s current breast cancer therapy, menopausal symptoms, work and family stressors, and sexual dysfunction. SSRIs and SNRIs can be extremely beneficial and cost-effective partly because of potential to reduce vasomotor symptoms (with the caveat that some of these drugs could interfere with the efficacy of tamoxifen, as described earlier in the section Antidepressants ). Short-term counseling, such as cognitive or behavioral therapy, can also be helpful.

Osteoporosis

Growing evidence indicates that bone health is of particular concern for women with breast cancer. Data from the WHI Observational Study, a prospective, longitudinal cohort of postmenopausal women, demonstrated a 31% higher risk of fracture in women with breast cancer. The cessation of HT use, the onset of chemotherapy-induced premature menopause, and the use of aromatase inhibitors and/or ovarian function suppressing medications all accelerate loss of bone and speed the development of osteoporosis. Chemotherapy itself may also adversely affect bone density, independent of any endocrine-mediated effect.

In a prospectively designed substudy of the Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) trial, bone mineral density (BMD) was assessed in 308 postmenopausal early-stage breast cancer patients at baseline and over 2 years of therapy. Anastrozole was associated with significant loss of BMD at the lumbar spine and total hip (median loss 4.1% and 3.9%, respectively), whereas tamoxifen was associated with BMD improvements (median increase 2.2% and 1.2%, respectively). The effect of anastrozole was most marked in women within 4 years of menopause. Fracture data were available for the full study population of 6186 women who completed 5 years of therapy. Three hundred and forty fractures (11%) were reported in the anastrozole group versus 237 (7.7%) in the tamoxifen group (odds ratio 1.49, CI 1.25–1.77). All three available aromatase inhibitors seem to affect bone turnover to a similar degree.

The American Society of Clinical Oncologists therefore recommends regular counseling about and screening for osteoporosis in women with nonmetastatic breast cancer ( Box 82.2 ). As for women without breast cancer, treatment ( Table 82.3 ) is recommended for those with osteoporosis (T score −2.5 or lower). For women with osteopenia (T score between −1.00 and −2.49), treatment decisions should be based on an individual’s fracture risk.

Counsel all women about adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, weight-bearing exercise, and smoking cessation

Assess bone mineral density annually by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scan if woman is:

- •

65 years or older

- •

60–64 years with other risk factors (family history of osteoporosis, low body weight, history of nontraumatic fracture, other risk factors)

- •

receiving aromatase inhibitor therapy

- •

has treatment-related premature menopause

- •

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree