Abstract

Misdiagnosis or delay in diagnosis of breast cancer is one of the most common causes of malpractice litigation. Many different issues account for the number of legal cases related to breast cancer, including failure to appropriately evaluate breast complaints, misinterpretation of imaging studies, failure to adequately sample (tissue) abnormal imaging or physical findings, and inaccurate pathological interpretation. Additionally, women who develop breast cancer who were at high risk because of genetic predisposition and did not receive proper instruction regarding genetic testing and/or more intense imaging recommendations have also sought redress.

Keywords

malpractice, delayed diagnosis, liability, legal

The delayed diagnosis of symptomatic breast cancer remains a leading source of error in clinical practice. Diagnostic errors in breast disease are but one component of the overall problem of diagnostic errors in medicine leading to liability. Based on a recent 25-year analysis of the US National Practitioner Data Bank, diagnostic errors, in general, occur at a rate of approximately 4000 per year (n = 100,249 liability claims for diagnostic error over 25 years). More specifically, diagnostic errors related to both asymptomatic and symptomatic breast cancer remain among the top 10 conditions leading to medical negligence lawsuits, according to the most recent analysis of 2157 closed claims carried out in 2013 by the Physicians Insurers Association of America (PIAA). Diagnosis of asymptomatic breast cancer occurs during population screening using mammography, or occasionally other radiologic methods. In contrast, diagnosis of symptomatic breast cancer applies to the patient presenting to a physician with detectible breast signs and symptoms. This chapter focuses solely on the delayed diagnosis of symptomatic breast cancer, which has a direct impact on physicians who are asked to evaluate the wide variety of signs and symptoms of benign and malignant breast disease. The problem of delayed diagnosis of symptomatic breast cancer is a worldwide problem, affecting all physicians in developed countries who evaluate breast disease.

It is important to distinguish delays in the diagnosis of asymptomatic breast cancer from those of symptomatic breast cancer because the two scenarios provide vastly different diagnostic strategies to the physician faced with evaluating breast lesions. Diagnostic delay in the asymptomatic patient relates to misinterpretation of screening mammograms (or other screening imaging modalities) in which the hallmarks of breast cancer are truly present but the images are misread as “normal.” This scenario might be better termed “the delayed diagnosis of radiographic- detectable breast cancer” and is largely confined to radiologists. In contrast, in the delayed diagnosis of symptomatic breast cancer, radiologic (e.g., mammographic) hallmarks of breast cancer are almost never present, and therefore radiographic images are read correctly as “normal.” This is truly a setting of radiographic- undetectable breast cancer. Unfortunately, in this setting, no further diagnostic studies beyond an unremarkable mammogram are usually undertaken, and so the patient’s symptomatic condition (e.g., unilateral breast mass, unilateral thickening, or isolated and focal breast pain) is labeled as “normal.” This distinction is critical because it is the absence of radiographic detectability in certain settings of symptomatic breast disease that is the driving force behind misdiagnosis. Knowing this distinction enables physicians to understand why relying on mammography as the sole diagnostic tool in the symptomatic setting leads to the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer.

Delays in diagnosis of symptomatic breast cancer involve prematurely labeling breast lesions as benign when in fact these lesions are later shown to be malignant. It is surprising that delays in diagnosis occur so frequently because there are a limited number of diagnostic elements used in the “diagnostic cycle of symptomatic breast disease.” The diagnostic cycle in symptomatic breast disease begins with a history and physical examination, continues with the use a variety of imaging modalities, and ends in biopsy of one type or another (fine-needle aspiration [FNA], core-cutting biopsy, or open biopsy). Although extremely short-term observation of breast lesions for 6 weeks or less may, in some cases after more thorough imaging studies, be interspersed in this diagnostic algorithm, this approach is fraught with hazard if the definitive diagnosis reveals breast cancer. It is the goal of this chapter to highlight for physicians that delays in the diagnosis of symptomatic breast cancer occur when the diagnostic cycle of symptomatic breast disease is interrupted prematurely, at the radiographic imaging stage. Fundamentally, the biology of symptomatic breast cancer differs from that of screen-detectable disease in the asymptomatic setting. Ultimately, the prevention of diagnostic delay in symptomatic patients requires completion of the diagnostic cycle by biopsy, regardless of normal findings on radiologic imaging. It is axiomatic that only tissue sampling by biopsy can definitively rule out breast cancer in the symptomatic setting.

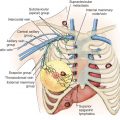

Given the limited number of diagnostic components—in essence, only the physician’s physical findings, the reports of imaging (mammogram, sonogram, or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]), and a decision regarding biopsy—one might presume that errors in diagnosis should occur infrequently. Yet historically, before introduction of radiologic screening technology, breast diagnosis experts such as Haagensen recognized the difficulties inherent in preventing the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer. Reflecting on his own 1% rate of diagnostic errors in breast cancer examinations over a 30-year interval, Haagensen’s writings emphasized that diagnostic errors occurred chiefly because many of the symptoms of breast cancer closely mimicked benign conditions, including masses, infections, and skin rashes. “The price of skill in the diagnosis of breast carcinoma is a kind of eternal vigilance,” Haagensen wrote, “based upon an awareness that any indication of disease in the breast may be due to carcinoma.”

Paradoxically, the advent of widespread radiographic screening for breast cancer has raised the diagnostic error rate in the symptomatic cancer setting far beyond the 1% reported by Haagensen. The PIAA 2013 report documents that the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer accounted for 22% of all indemnity claims in their database. Of these claims, nearly two-thirds (59%) were breast conditions labeled as benign that later proved to be malignant disease. Unfortunately, the modern area of breast imaging has been accompanied by an increased rate of delays in diagnosis of symptomatic breast cancer, despite the promises to the public of improved detection rates for breast cancer. This fact is not well known to physicians involved in the diagnosis of breast disease. When 400 expert physicians (pathologists, medical oncologists, and surgical oncologists) were recently surveyed as to what top five cancers they believed were most frequently misdiagnosed, they ranked breast cancer as number two on the list. Surprisingly, these expert physicians felt that significant delays in the diagnosis of cancer occurred only rarely, at rates of less than 10% of presenting cases. The missed diagnosis of symptomatic breast cancer is often thought of as simply the result of substandard medical care by “bad physicians.” However, the events that lead to misdiagnosis are far more complex, and the numbers of diagnostic errors far too numerous, to be ascribed solely to individual physician competency. In fact, underlying misdiagnosed symptomatic breast cancer are unique features of the disease, and misunderstood uses of radiologic imaging, that make delays in diagnosis not only possible but, under certain conditions, highly probable. For example, delayed diagnosis of breast cancer almost always involves a specific category of patients, an identifiable specialty of physicians, and a reproducible set of clinical circumstances. These three factors interact to produce delays in diagnosis that are frequent, and often lengthy. This chapter attempts to outline in more detail the individual components leading to high-probability scenarios for diagnostic error in symptomatic breast cancer.

Because delays in diagnosis of symptomatic breast cancer occur repeatedly under certain clinical conditions, it follows that the circumstances producing diagnostic failures should be predictable and that diagnostic delays should be avoidable. A thorough understanding of the causes and consequences of the delayed diagnosis of symptomatic breast cancer is central to risk management for clinicians managing breast disease. Ultimately, an analysis of the determinants of delayed diagnosis of breast cancer in the symptomatic setting is an important and useful tool in defining the limits of the perceptual, cognitive, and radiologic detection of breast cancer, by patients and clinicians alike.

Magnitude of the Problem

In terms of all diagnostic errors among providers of primary health care to women, the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer ranks among the top three misdiagnoses, as shown in Box 86.1 . This list was created from data compiled in 1995 and 2001 by the PIAA. The PIAA is an insurance trade association of 25 domestic insurance companies that provide malpractice insurance to more than 90,000 physicians in the United States. The data represent indemnity claims over the 16-year interval from January 1985 to December 2000.

General Surgery

- 1.

Breast cancer

- 2.

Appendicitis

- 3.

Spinal fracture

Family Practice

- 1.

Myocardial infarct

- 2.

Breast cancer

- 3.

Appendicitis

Internal Medicine

- 1.

Lung cancer

- 2.

Myocardial infarct

- 3.

Breast cancer

Obstetrics/Gynecology

- 1.

Breast cancer

- 2.

Ectopic pregnancy

- 3.

Pregnancy

Radiology

- 1.

Breast cancer

- 2.

Lung cancer

- 3.

Spinal fracture

More recently, The Doctors Company, the nation’s largest physician-owned insurance company with 77,000 insured member-physicians, published data on 1877 specialty-specific, diagnosis-related claims closed between 2007 and 2013. The delayed diagnosis of breast cancer ranked between first and third on the list of top five diagnostic errors in the specialties providing health care to women: obstetrics and gynecology (first most common, 21.4% of 98 claims); general surgery (second most common, 9.8% of 143 claims); family medicine (third most common, 4.1% of 417 claims). The 2013 PIAA study (1a) of more than 2000 breast cancer malpractice claims closed between 2002 and 2011 noted the following rank order of physician specialty involved in diagnostic delays: radiology, 43%; obstetrics and gynecology, 16%; general surgery, 12%; family practice, 8%; internal medicine, 8%; and other, 13%.

A recent study of 4793 claims filed against 2680 radiologists documented that failure to diagnose breast cancer was the most common source for liability claims, occurring at a rate of 4.13 claims per 1000 person years. In 2015, The Doctors Company partnered in a liability study with CRICO Strategies, which is the medical malpractice insurer for the Harvard medical community and other non–Harvard-affiliated hospitals located across the United States. These liability companies jointly analyzed 562 breast cancer malpractice claims from 2009 to 2014. These claims were drawn from an overall database of 300,000 medical malpractice claims from more than 500 hospitals and 165,000 physicians across the United States.

In the CRICO study, of 342 malpractice claims involving failure to diagnose breast cancer, the following key factors were noted. First, 48% of cases (163) involved radiologists, and 39% of cases (135) involved physicians in family practice and obstetrics and gynecology. Second, the misreading of mammograms as “normal” when hallmarks of cancer were truly present accounted for 49% (162) of cases. Third, in 27% of cases (94 claims), the medical records showed that diagnostic delay resulted from a failure to order any diagnostic testing beyond physical examination alone. Fourth, the failure or delay in obtaining additional opinions from experts in breast disease accounted for 17% (57) cases. And last, the severity of outcomes for 69% of patients sustaining diagnostic delays (239 cases) was “severe” (death, permanent grave or major harm), with 13% of delays associated with death (43 cases). These studies confirm earlier claims data analyses reporting that 24% (44 of 181 claims) of diagnostic delays in the ambulatory medical setting were related to breast cancer.

Physicians and their medical malpractice insurers bear a heavy financial burden resulting from the delayed diagnosis of symptomatic breast cancer. In general, malpractice claims related to diagnostic errors account for 30% to 40% of liability payments, and average approximately $300,000 per claim. More specifically, the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer is the second most expensive area of claims to indemnify by liability carriers. Tables 86.1 and 86.2 demonstrate these findings and compare the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer with four other common and expensive conditions resulting in malpractice actions. The 2013 PIAA liability study reported that the average indemnity payment for breast cancer claims of “severe” harm and death was $350,000 and $500,000, respectively.

| Condition | No. of Patients | Average Cost Per Case |

|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | 3370 | 212,894 |

| Brain-damaged infant | 3308 | 487,839 |

| Pregnancy | 2656 | 159,922 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 2336 | 180,506 |

| Condition | No. of Patients | Total Paid (Millions) |

|---|---|---|

| Brain-damaged infant | 3308 | $754.20 |

| Breast cancer | 3370 | $295.80 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 2336 | $155.90 |

| Pregnancy | 2657 | $122.40 |

For example, in 1990, the PIAA noted that the delayed diagnosis of cancer, in general, accounted for 2956 claims out of a total of 15,356 claims for diagnostic errors. Indemnity payments for misdiagnosed cancer approached $200 million annually, or approximately 30% ($194 million out of $698 million) of paid-out liability claims for medical misadventures. Even by 2001, indemnification of misdiagnosed cancer continued to represent almost 8% of the 16-year liability payout by insurers ($8.5 billion). A third study by the PIAA, published in 2003, continued to document that the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer remained the leading cause of malpractice claims against physicians.

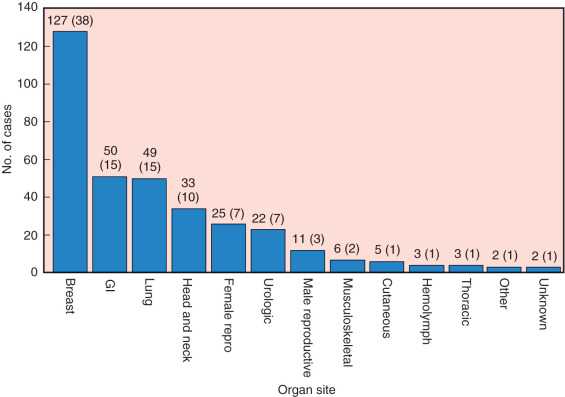

Kern corroborated the frequency and expense of misdiagnosed breast cancer using data derived from our own nationwide medicolegal study of 338 cases of misdiagnosed cancer occurring in 13 major organ sites, as shown in Fig. 86.1 . This histogram illustrates that breast cancer ranked first in misdiagnosed cancer, accounting for 127 of 338 cases. The delayed diagnosis of breast cancer exceeded the next most common organ site involved in diagnostic delays, colon cancer, by more than twofold (38% vs. 15%). Kern’s study demonstrated that the expense of liability claims for misdiagnosed breast cancer totaled more than $50 million, or 38% of the combined total, for all 13 organ sites, of $133 million. In Kern’s 1995 article reviewing 711 negligence claims in the field of general surgery, breast cancer claims again ranked first on this list, with 172 cases (24%) of the total caseload of 711 liability claims. Despite the frequency with which general surgeons evaluate and treat breast cancer, misdiagnosis of this condition ranks first in diagnoses resulting in negligence litigation against general surgeons.

Other studies have supported these findings. In 1988 the St. Paul Fire and Marine Insurance Company, a large medical liability carrier, reported that failure to diagnose cancer was the third most frequent allegation against physicians. Of these diagnostic delays, one-third focused on breast cancer. In 1963 Harper reviewed 1000 cases of litigation while serving as a medicolegal defense consultant to California insurers. The delayed diagnosis of cancer was reported in 1.4% of negligence cases (42 of 1005 cases), equally divided among cancers of the rectum, breast, and cervix. In a study of 1371 malpractice claims from an insurance survey in New Jersey, Kravitz and collaborators noted that breast operations accounted for 9% (26 of 304) of general surgery operations resulting in negligence claims. In 2006 Gandhi and colleagues reviewed 181 malpractice claims in the ambulatory setting. The most common misdiagnosis was cancer (59%, 106 of 181 cases), and the most common cancer misdiagnosed was breast cancer (24%, 44 of 106). In 2007 Singh and associates performed a comprehensive analysis of published literature in the field of diagnostic errors, which also supported the finding that breast cancer is the most frequently misdiagnosed cancer.

The frequency of delayed diagnosis of breast cancer is not a direct result of the high incidence of breast cancer in the population. Data tabulated in our 1994 study of delayed diagnosis of cancer nationwide illustrate that the frequency of delayed diagnosis of breast cancer is twice as great, on a proportionate basis, as the frequency of breast cancer in the US population. The mortality rate of breast cancer patients from this medicolegal study was no different from that of breast cancer patients in the 1973 to 1987 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute, when calculated on a proportionate basis (the absolute difference in mortality rates was 1.2 between delayed diagnosis cases and SEER cases). The proportionate mortality rate of breast cancer patients with delayed diagnosis was 13% (17 deaths in 127 cases of delayed diagnoses), compared with a mortality rate of 11% for the SEER breast cases (24 deaths from breast cancer per 105 population/212 breast cancer events per 105 population).

The 2013 PIAA study also showed a discrepancy between the US incidence rates for breast cancer and the rank order of 2157 closed liability claims involving breast cancer. Whereas breast cancer is the second most common cancer reported in the National Program of Cancer Registries (122 cases per 100,000 women), it ranks first in the number of closed liability claims compared with nine other common malignancies (including prostate, lung, colorectum, uterine, bladder, lymphoma, melanoma, and renal cancer). There is something truly unique about the diagnostic approach to symptomatic breast cancer that results in this disease occupying the number one position for frequency of liability claims against physicians.

Unfortunately, there is strong evidence that many clinicians do not fully understand the correct approach to promptly diagnosing symptomatic breast cancer. This evidence is derived from medical malpractice claims for failure to diagnose breast cancer, as described in the preceding discussion. When stratified by which actions on the part of physicians are most costly to malpractice carriers, manual examination of the female breast ranks 9 out of 20, accounting for $38 million (162 claims out of 8234 total malpractice cases, or 2%). An approximate calculation of the number of misdiagnosed breast cancers resulting in litigation may be derived from findings accrued by the PIAA. This group defends approximately 300 cases of misdiagnosed breast cancer each year among its 100,000 insured physicians (encompassing a wide range of specialties). Because there are about 1 million physicians in the United States, with roughly one-third caring for adult women, it can be estimated that there may be as many as 1000 cases per year of misdiagnosed breast cancer undergoing evaluation for medical negligence (average, 20 cases per state). This represents 0.5% of the new cases of invasive breast cancer (180,000) diagnosed each year.

Several factors contribute to persistence of errors in the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer. First, breast cancer and benign breast disease are common, and both may adopt similar signs and symptoms. The American Cancer Society reported that nearly 232,000 new cases of invasive female breast cancer occurred in 2015, or approximately 123 cases per 100,000 females, were diagnosed in 2015. Estimates of the number of breast biopsies performed in the United States are reflective of the volume of benign breast disease, which includes 250,000 open surgical procedures and 37,000 needle biopsies of palpable breast lesions. Second, clinically occult, undetectable breast cancer is present in up to 10% of women. Holford and coworkers showed that the percentage of women with breast cancer at autopsy in whom the diagnosis was overlooked antemortem ranged between 3% and 11%. Both contralateral biopsy and prophylactic contralateral mastectomy have revealed an incidence of occult breast cancer of 5% to 10%. Thus, some fraction of women presenting with breast symptoms who do not have a biopsy performed initially (for defensibly correct reasons) will later be diagnosed with breast cancer that was detected incidentally. Finally, many physicians evaluate breast complaints. In the absence of specialists in the field or well-defined clinical practice guidelines, errors in diagnosis are bound to occur. In particular, failure to biopsy a breast mass is a leading source of error. Indeed, the failure to biopsy is one category of “errors of omission” leading to malpractice in oncology, in which physicians are being sued for “not doing something right” (as opposed to “doing something wrong”).

Definition of Delayed Diagnosis of Breast Cancer

Delayed diagnosis of breast cancer may be classified in several ways because the terminology applied to diagnostic delays is not standardized. Specific classifications of delayed diagnosis of breast cancer are based on who is primarily responsible for the delay: the physician, the patient, or the medical system itself. This chapter focuses on the general categories of patient- and physician-associated delays in the diagnosis of breast cancer.

Patient-Associated Delays in Diagnosis

Studies of Patient-Associated Delays in Diagnosis

Regardless of the type of cancer under review, studies of the delayed diagnosis of cancer have shown that most delays occur before medical consultation. This finding has been noted for more than 60 years. For example, in 1943 Harms and colleagues studied 158 cancer patients and reported that the median interval between the onset of symptoms and treatment was 8.5 months. Breast cancer had the second longest delay time in presentation to a physician, surpassed only by cancer of the skin.

While studying a wide range of cancers, Mor and colleagues showed that 25% of cancer patients delayed seeking medical consultation for more than 3 months. Other studies have shown similar results, with 35% to 50% of cancer patients delaying more than 3 months before seeking medical attention. Hackett and coworkers in a study of 563 cancer cases from the Massachusetts General Hospital with a wide range of diagnoses, showed that 15.6% of cancer patients delayed their presentation to a physician for more than 1 year. Hackett reported that between the years 1917 and 1970, only modest decreases in the length of delayed diagnosis of cancer of all types were appreciated. In the years 1917 to 1918, delays averaged 5.4 months; between 1921 and 1922, the average delay was 4.6 months; and by 1930, the delay interval remained at 4.8 months. The median time to presentation was 3 months.

Hackett and coworkers created a kinetic curve describing the rate of presentation for medical evaluation versus time. These investigators demonstrated that the half-time rate of delay for patients presenting to physicians with a variety of cancer types was slightly greater than 2 months. Based on this kinetic analysis, it can be predicted that 10% to 20% of cancer patients will never consult their physician about their symptoms. These results serve as a mathematical predictor that a group of patients will demonstrate extraordinarily long symptomatic intervals before presenting to a physician for diagnosis.

Clinical studies have confirmed this mathematical prediction. For example, Aitken-Swann and Paterson reported a series of patient interviews with British cancer patients. In this study, approximately 50% of cancer patients with a variety of tumors delayed seeking advice for 3 months or more, and 25% of cancer patients delayed seeking treatment for a year or more after first noticing symptoms. In a subset of women with breast cancer, Wool confirmed that symptomatic delays could reach extraordinarily lengthy intervals, with some patient-associated delays approaching 2 to 3 years.

Historically, studies specific to the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer have shown that diagnostic delays were usually long. Nonetheless, a chronologic analysis demonstrates that delays have been steadily decreasing over time. In 1892 Dietrich (as reported by Bloom and Richardson ) reported that only 23% of breast cancer patients presented within 6 months of discovering their breast tumor. Over the next 50 years, the proportion of patients sustaining lengthy delays continued to decrease. By 1910 to 1914, Harrington, at the Mayo Clinic, reported that 33% of breast cancer patients were treated within 6 months of discovery of a breast tumor and 54% were treated in less than 1 year. By the late 1930s, these proportions had increased to 50% and 70%, indicating earlier diagnosis of these cases. Lewis and Reinhoff in the late 1930s, and later, Eggers and deCholnoky in the 1940s, reported less optimistic findings, with only 34% of patients seeking medical advice within 6 months, and 55% seeking advice within 1 year. By the 1950s, Bloom and Richardson ; Bloom ; and Bloom, Richardson, and Harries reported on a series of 406 patients and showed that 65% of the patients sought treatment within 6 months of the first symptom, and 85% of patients presented for evaluation within 1 year. Hultborn and Tornberg reported 517 cases from the years 1930 to 1955. Thirty percent of the patients presented for treatment in less than 1 month, 37% in less than 6 months, and 22% in less than 1 year. Between 1930 and 1955, there was no change, on a proportionate basis, in the rate at which patients presented for diagnosis.

In 1959 Waxman and Fitts reported on 740 patients with breast cancer and showed that, between the years 1940 and 1951, the number of patients reporting their symptoms to a physician within 1 month of self-discovery increased 10%. The authors attributed this effect to increased publicity about breast cancer. Robbins and Bross compared the range of pretreatment symptom delays in 3802 patients treated with radical mastectomy between 1940 and 1955. Patients were divided into two groups: those treated between 1940 and 1943 and those treated between 1950 and 1955. In the patients from the 1940s, delays of less than 2 months were present in 42.9% of patients, compared with 47.5% of the patients in the 1950s. Delays exceeding 6 months were present in 30.8% of the 1940s group, and 27.7% of the 1950s group. Between the two time periods, the median delay for delayed presentation of symptoms dropped by only 0.8 month. Tumor sizes at presentation in these same time periods showed a shift downward at diagnosis in 2% to 10% of patients. For patients in the 1940s (1281 patients), T1 tumors (<2 cm) were present in 20%; T2 tumors (<4 cm), 46.7%; and T2 tumors (>4 cm), 33.3%. In the 1950s group (2168 patients), these same figures were T1, 28.4%; small T2, 48.7%; and larger T2, 22.9%.

More recent studies have shown a continued decline in the time to presentation for medical evaluation after the appearance of the first symptom of breast cancer. In 1971 Sheridan and associates reported that in 1860 women in Western Australia, 24% had delayed seeking treatment for 1 to 4 weeks, 32% delayed 1 to 3 months, 18% delayed 3 to 6 months, and 6% delayed more than 6 months. A small fraction of patients (2%) sustained lengthy delays in presentation of 4 years or more. Only 5% of patients visited a physician within 1 week of symptoms. Nichols and coworkers confirmed that 23% of women delayed consultation for more than 3 months. Gould-Martin and associates reported that in a study of 275 women 40 to 65 years of age who had breast cancer, 7% of patients delayed for more than 6 months before seeking medical attention. Waters and colleagues and Cameron and Hinton noted that 20% to 30% of patients delayed presentation to a physician for more than 3 months. Pilipshen and associates reported in 1984 that 63% of breast cancer patients treated at Memorial Hospital in New York delayed for less than 2 months. Robinson and coworkers studied 523 women with breast cancer and noted a mean delay from symptoms to diagnosis of 5.5 months (median, 4 months). Mor and coworkers studied nearly 500 breast cancer patients and showed that one-third of patients delayed presentation to a physician after the onset of symptoms for more than 3 months. Rossi and colleagues demonstrated that the median symptom-delay time was 2 months, with 35% of women waiting more than 3 months before presenting to a physician.

Keinan and coworkers noted that typical delays for American and Canadian women from symptoms to diagnosis were 3 to 6 months. Katz and associates, in a study of women in Washington State and British Columbia, noted that 16% to 17% of patients had a symptom-delay time of 3 months and 13% had a symptom-delay time of 6 months. Diagnosis-delay times of 3 months were present in 4.6% of Canadian patients and 13.1% of American patients; patient-associated diagnostic delays exceeding 6 months were present in 3.5% and 11.4% of Canadian and American patients, respectively. In 1995 Andersen and Cacioppo confirmed that the mean delay time from a patient first noticing a symptom to clinical evaluation by a physician was 3 months. In a subset of women, delays can be extreme, approaching 2 to 3 years. Given the large number of new cases of breast cancer diagnosed in American women in 2003 (211,000), it has been estimated that in that time frame, more than 70,000 American women will sustain patient-associated diagnostic delays exceeding 3 months.

Patient-associated delays approximating 3 months from the onset of symptoms to presentation to a physician appear to be universal throughout the developed world. In a study of Australian women, Margarey and colleagues confirmed that 25% of patients delayed presentation to a physician for more than 4 months. In a study of 48,000 women from Sweden, Mansson and Bengtsson noted that the average delay from symptom detection to visiting a physician was 5 months and that only 40% of women visited a physician within 1 month of symptoms. In the developing world, delays may extend over a far greater period. Goel and associates noted that in India, the average patient-delay time was 6.7 months. Ajekigbe noted similar results in Nigeria, and Chie, and Chang confirmed lengthy patient-associated diagnostic delays in Taiwanese patients.

Physician-Associated Delays in Diagnosis

Compared with patient-associated delays, the many factors accounting for physician-associated delays in diagnosis are less well studied. Facione noted that the true extent of provider delay is underresearched and underestimated. However, since the 1930s, it has been recognized that physicians are responsible for the majority of delay in the time from symptom detection to the diagnosis of breast cancer. In 1926 Lane-Claypon reported that in a series of 670 breast cancer cases, the average interval from first medical consultation to treatment averaged 6 months. Pack and Gallo, in a series of 1000 patients, stated that physicians were solely responsible for 17% of delays in diagnosis. These authors proposed that an equal number of delays resulted from the combination of patient and physician delays. Rimsten and Stenkvist, confirming earlier reports of Leach and Robbins, noted that physicians were responsible for diagnostic delays in 28% of patients; physicians contributed to the combination of patient-physician responsibility in another 11%. In a series of 400 patients, Kaae noted that physicians were responsible for delays in diagnosis in 12% of cases. As will be discussed later, these diagnostic delays were often related to the patient’s age: women 40 years of age or younger were twice as likely to sustain delays in diagnosis compared with women older than age 50.

The relationship between the age of patients and delays in diagnosis of breast cancer has been noted since the 1940s. Harnett found that in a series of 2000 patients with breast cancer, biopsy was delayed in 7% of patients because of a physician’s missed diagnosis. More than 25% of these biopsy delays occurred in patients younger than age 50. Rimsten and Stenkvist noted that 25% of women younger than age 50 sustained a delay in diagnosis ranging from 4 months to 2 years and that physicians were solely responsible for these delays in nearly 25% of patients. Nichols and colleagues noted that 10% of malignant breast diseases were delayed in their diagnosis by physicians for more than 1 month. Robinson and coworkers noted that physician-associated delays in diagnosis occur in 8% to 30% of patients.

Physician Factors in Delayed Diagnosis of Breast Cancer

Interval of Diagnostic Delay

Physician-associated errors in diagnosis tend to follow reproducible and predictable patterns. Kern found that the average length of a delay in diagnosis of breast cancer was 15 months, with a median length of diagnostic delay of 11 months (90th percentile, 24 months). Others have confirmed this average length of diagnostic delay in breast cancer. In a 1992 study, Kern found that the range of diagnostic delay in 37 cases was 1 to 60 months from the time of the patient’s presentation to the biopsy-proven diagnosis of breast cancer. Broken down on a yearly basis, 67% (25 of 37) of patients were diagnosed as having breast cancer within 1 year, 78% (29 of 37) of patients within 2 years, and 95% (35 of 37) of patients within 3 years.

A comparison of intervals of diagnostic delay in breast cancer to 10 other cancers was also performed by Kern in a 1994 study. The mean length of diagnostic delay for 212 cases was 17 months, with a median of 12 months (90th percentile, 33.5 months). This comparison shows surprisingly similar lengths of median diagnostic delay among the 13 types of cancers, including cancer of the colon (11 months), thyroid cancer (12 months), and cancer of the lung (15 months).

In a study of 338 misdiagnosed cancers nationwide, Kern found that 156 cases were recorded with a death or terminal condition (46%, or 156 of 338). These cases were not all breast cancers. In 88 of the fatal cases, the length of diagnostic delay was known and averaged 16 months, with a median length of delay of 12 months (90th percentile, 25 months). This length of delay was not different statistically from the 17-month average delay of the entire group of 212 cases. Kern also analyzed the lengths of diagnostic delays for 296 cancers overall in relation to the outcome of subsequent malpractice litigation. No statistical difference was found in the average lengths of diagnostic delays between defense verdicts (14 months, n = 64), plaintiff verdicts (19 months, n = 61), settlements out of court (17 months, n = 83), and all deaths (16 months, n = 88). In addition, the data demonstrated similar lengths of diagnostic delay between patients who died, patients who succeeded in their lawsuit, patients who lost their lawsuit, and patients who settled their negligence lawsuits out of court.

A frequency distribution by 3-month intervals of the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer, derived from my previous civil court study, demonstrated a bimodal distribution of diagnostic delays, with the first peak at 7 to 9 months and a second later peak at 31 to 33 months of delay. Kern analyzed the diagnostic delays in 273 cases from the PIAA 1990 study of misdiagnosed breast cancer, grouping delays in 5-month intervals. Here, a single peak at 6 to 11 months of delay was found, with a long tail to the frequency distribution curve, extending out to 72 to 77 months. On the basis of these data, it appears that most cancers make their presence known after misdiagnosis within 1 year; however, a smaller fraction continues to go undiagnosed for lengthy periods.

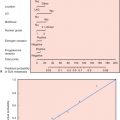

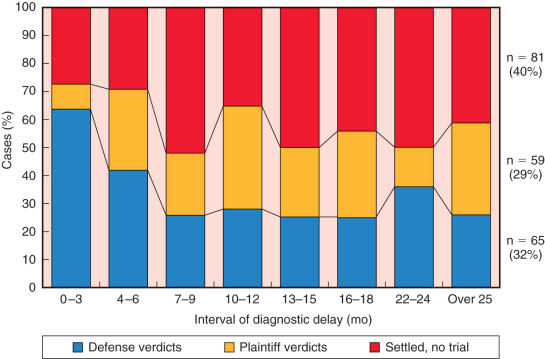

On the basis of the data from my nationwide study of 338 cases, the outcomes of litigation were correlated versus the lengths of diagnostic delay, categorized by 3-month intervals, as shown in Fig. 86.2 . The 205 verdicts were divided into 65 defense verdicts (32%), 59 plaintiff verdicts (29%), and 81 settlements out of court (40%). At less than 3 months, the 11 jury verdicts largely favored the defense in the following proportion: 64% defense verdicts (7 of 11), 9% plaintiff verdicts (1 of 11), and 27% settlements out of court (3 of 13). At 4 to 6 months, the proportion of defense verdicts decreased to 42% (13 of 31), plaintiff verdicts rose to 29% (9 of 31), and settlements also rose to 29% (9 of 31). By 7 to 9 months, defense verdicts decreased further still but stabilized at the level of 26% (7 of 27), plaintiff verdicts remained roughly the same at 22% (6 of 27), and settlements stabilized at 52% (14 of 27). Grouped by 3-month intervals thereafter (10–12 months, 13–15 months, 16–18 months, 22–24 months, and more than 25 months), the proportion of verdicts remained roughly the same. With diagnostic delays of more than 25 months, the verdicts were 26% (7 of 27) for the defense, 33% (9 of 27) for the plaintiff, and 41% (11 of 27) for settlements out of court.

How juries view delays in diagnosis as negligent is a complex and incompletely understood process. Experimental research on jury decision-making has focused on criminal cases, and little is known about how juries in civil trials of medical negligence allocate liability among parties or assess compensatory and punitive damages. One theory, derived from basic research on human judgment, suggests that juries reach decisions through an information-integration model, in which evidence is mentally averaged until a decision threshold is reached. Thereafter, exact statistics are disregarded in favor of the mentally weighted average. This model best explains the decline in number of defense verdicts at 3 months and the stabilization of these verdicts after 6 months. Apparently, juries view 6 months of diagnostic delay as the threshold for negligent delay in diagnosis. Beyond this point, the length of diagnostic delay, or survival of the patient, appears to be irrelevant to the jury’s final deliberation. Others have suggested that defensibility of breast cancer malpractice falls dramatically at 12 months of diagnostic delay.

Specialty Training of Physicians

The specialty distribution of physicians involved in diagnostic delay from Kern’s 1992 study was obstetricians and gynecologists in 21 of 42 cases (50%), family practitioners in 15 of 42 cases (36%), general surgeons in 12 of 42 cases (29%), radiologists in 4 of 42 cases (10%), and internists in 2 of 42 cases (5%). The numbers of physicians involved in these 42 cases ranged from one to four in each case. The distribution of physicians involved in these cases was one physician in 27 cases, two physicians in 10 cases, three physicians in 3 cases, and four physicians in 2 cases.

A frequency distribution of the specialty training of physicians, created from data from two PIAA studies of the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer, is shown in Fig. 86.3 . This histogram compares two time periods, demonstrating a change in the specialty distribution of physicians involved in delayed diagnosis. In 1990 the three most frequently implicated physician specialties in the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer, in rank order, were obstetricians and gynecologists, family practitioners, and general surgeons. This distribution in 1990 was consistent with my findings, published in 1992. A reassessment of data reported by the PIAA in 1995 showed that radiologists had increased in frequency of misdiagnosis from 20% of the total cases to involvement in 80% of the cases. In 487 cases reported by the PIAA in 1995, 917 physicians were involved in delayed diagnosis. On average, two physicians were involved in each case. The increase in radiologists involved in diagnostic delays between 1990 and 1995 suggests that more emphasis is being placed on mammographic interpretation of breast findings suggestive of cancer. When the diagnosis of detectable breast cancer is delayed, both the radiologist and other primary care providers to the patient might be named in any negligence lawsuit. More recent data from the 2013 PIAA claims study confirms an increase to 43% in involvement by radiologists in the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer.

Diagnostic Workups Requested by Physicians

Studies by Kern in 1992 and 1994 determined that the diagnostic workup of patients who were misdiagnosed was largely inadequate, reflecting the mistaken idea that these women with breast masses could not have breast cancer. For example, 51% (23 of 45) of patients in Kern’s 1992 study had no workup of breast masses beyond visual observation and physical examination alone. Forty-four percent (20 of 45) of patients underwent mammography. Of the 20 mammograms performed, 80% (16 of 20) of the results were read as normal, despite the presence of a malignant breast mass. Only one patient (2%) underwent FNA biopsy, but this patient had a false-negative result, leading to a diagnostic delay. No patients underwent ultrasonographic evaluation.

Clinical Scenarios Leading to the Delayed Diagnosis of Breast Cancer by Physicians

There are several well-recognized clinical scenarios that lead to delays in diagnosis on the part of physicians. The following sections present the clinical scenarios leading to these inadequate workups of symptomatic breast disease.

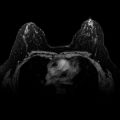

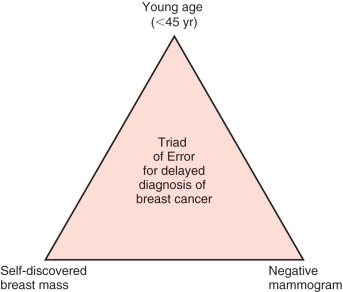

Triad of Error for Delay in Diagnosis of Breast Cancer

In several previous publications, Kern has proposed that women are at the highest risk for receiving a delayed diagnosis of breast cancer when they fulfill these three criteria: (1) they are 45 years of age or younger; (2) they present to their physician with a self-discovered, unilateral breast mass; and (3) they undergo “screening” mammography as an attempted diagnostic tool, which results in a false-negative study (the mammogram fails to image their breast mass). To help clinicians remember these elements, Kern has named them the Triad of Error for misdiagnosed breast cancer, succinctly stated as follows: Young age, Self-discovered breast mass, and Negative mammogram ( Fig. 86.4 ). Patients who harbor this triad sustain misdiagnosis of breast cancer in more than three-fourths of cases. These patients are believed to be too young to develop breast cancer, and their mammograms, if obtained, are often read as negative, despite the presence of a breast malignancy. An analysis of actual medical malpractice litigation reveals that physicians are lulled into the misdiagnosis of breast cancer by the young age of patients, not by vague findings or difficult diagnostic situations. Data from medicolegal studies show that in more than 80% of misdiagnosed breast cancers, a physical finding clearly compatible with breast cancer is present. Because of the relative youth of these patients, physicians are not aggressive enough in pursuing a diagnosis beyond mammography. Unfortunately, in this setting, physicians often believe a negative mammogram is sufficient proof of benign disease, even in the presence of a breast lump. This is the classic clinical scenario leading to the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer and subsequent cases of medical malpractice. Much of the evidence for the Triad of Error comes from Kern’s studies of the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer and its attendant malpractice litigation. Medicolegal data were analyzed from several perspectives, including a clinical, historical, and risk prevention viewpoint. The following paragraphs evaluate each of the legs of the Triad individually.

Young Age.

Most patients in whom the diagnosis of breast cancer is delayed are young, with a median age of 42 years. In Kern’s previous 20-year review of the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer, 45 cases of breast cancer malpractice litigation tried in the US federal and state civil court system between 1971 and 1990 were critically analyzed. In 21 cases in which a patient’s age could be identified, the patients were young, with a mean age of 40 years (range, 22 through 59 years). When cases were grouped by 10-year intervals, the ages of patients were as follows: 4 (19%), 20 to 29 years; 8 (39%), 30 to 39 years; 5 (30%), 40 to 49 years; and 4 (19%), 50 to 59 years. Of the patients with known ages, 4 (19%) were younger than 29 years of age; 11 (52%), younger than 39 years of age; 16 (76%), younger than 49 years of age; and all patients younger than 59 years of age. The menopausal status of the patients was identified in 25 (55.5%) of cases. Of these 25 women, 68% were hormonally active, 15 (60%) were known to be premenopausal, and 2 (8%) were pregnant. Postmenopausal women made up only 5 (11.1%) members of the group. The PIAA 1995 Breast Cancer Study noted the average age of misdiagnosed patients was 46 years, an increase of 2 years over the average age of 44 years reported in their previous 5-year study.

More current claims studies have continued to demonstrate the extraordinarily young age of misdiagnosed breast cancer patients. In the 2013 PIAA claims review of 2157 cases, the median age range was 40 to 49 years, which constituted 32.7% of all cases. Patients aged 30 to 39 comprised 15.9% of cases, and those under age 30 comprised 4.1% of cases. Those patients 50 to 59 years accounted for 26.3% of cases, followed by those 60 to 69 years (11.6% of cases), with those greater than 70 years of age comprising 4.9% of cases.

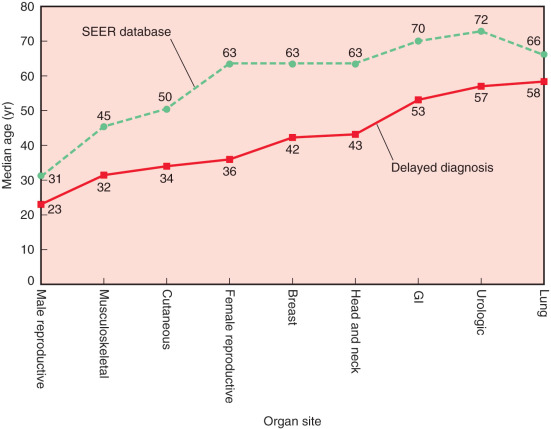

Perhaps the most important finding from my Kern’s medicolegal study was that misdiagnosed breast cancer patients are on average 20 years younger than the median age of breast cancer patients in the US SEER/NCI database, which is 63 years. This same finding of misdiagnosed patients being younger than those reported in cancer databases holds true for other types of misdiagnosed cancer as well. Fig. 86.5 illustrates the age differential in misdiagnosed cancer patients from our study of delayed diagnosis in 13 different organ sites. For all organ sites, a delayed diagnosis occurred in patients at a younger age than the typical age of presentation in the SEER population. The difference in median ages between diagnostic delays and the SEER database ranged from 8 to 27 years. On average, patients with diagnostic delays were younger than SEER patients by 16.2 years (standard error, 2 years).

Kern refers to the age differential in misdiagnosed cancer as a litigation gap rather than an age gap, because the young age of cancer patients, in general, leads to delays in biopsy and specialized radiographic imaging, which often results to malpractice litigation. As it relates to breast cancer, other studies have confirmed these findings that misdiagnosed patients are younger than the typical population at risk. Diercks and Cady also confirmed a median age of 42 years for 57 patients in Massachusetts in whom the diagnosis of breast cancer was delayed. Max and Klamer studied 120 women younger than 35 years of age who had breast cancer. In this group of women, who had a mean age of 31 years, 9.1% were pregnant or lactating. Delays in diagnosis were common: in 7% of patients, physicians delayed more than 2 months before recommending a biopsy. In this study, 61% presented with a painless lump; mammography was done in 61% of patients, and in 52% of this group, mammography was negative. In 11% of patients, mammography was equivocal and did not lead to biopsy. Pregnancy-associated delays in diagnosis are discussed more completely later in this chapter but are mentioned here to emphasize the importance of young age as a cause of misdiagnosis. The average age of pregnant patients with breast cancer is 32 to 38 years. However, pregnant patients harboring breast cancer can be extremely young, and some have been described to be as young as 16 to 18 years of age. This is in contrast to nonpregnant patients, in whom breast cancer before age 20 to 25 is extraordinarily rare. In a series of 95 adolescent girls with breast masses, Hein and coworkers showed there were no breast cancers in these young women, who had an average age of 15.9 years (range 12–20 years). However, the authors noted two cases of cystosarcoma phyllodes.

The young age of patients with the delayed diagnosis of cancer is a unique aspect of negligence litigation in malignant disease. Generally, elderly women are more likely to sustain negligence-related, adverse medical events not related to breast cancer. For example, in one study, patients older than 64 years were twice as likely to experience legally compensable complications during hospitalization as patients younger than 45 years of age. Many physicians are unaware that nearly one-fourth of all breast cancer deaths occur in women whose age is not usually associated with the presence of breast cancer. Two percent of breast cancers occur in women between 15 and 34 years of age, 10% occur in those younger than 40 years of age, and 21% occur in women between 35 and 54 years of age. A recent study of the rates of breast cancer in women 30 years of age or younger with breast masses found the incidence of cancer was 2.5%. McWhirter calculated that each general practitioner in England is likely to see a case of breast cancer in women younger than 40 years of age only once in every 15 years of his or her working life.

Self-Discovered Breast Mass.

Palpable masses are often present in misdiagnosed women with breast cancer. In Kern’s civil court analysis of 45 cases of misdiagnosed breast cancer, definite physical findings were present in 82% (37 of 45) and included the following: painless mass, 64% (29 of 39); painful mass, 9% (4 of 45); and nipple discharge (bloody or green) or rash, 6% (3 of 45). Thus 73% of misdiagnosed breast cancer patients presented with a self-discovered breast mass. This finding was confirmed in a larger series of 127 breast cancer cases, in which 61% of patients presented with a breast mass. In the 1990 PIAA study of misdiagnosed breast cancer, the findings at physical diagnosis were reported. In 273 cases, 62.1% (159 of 273) presented with a mass without palpable axillary nodes, and 9.8% (25 of 273) presented with a mass and palpable nodes. Thus 72% of patients with delayed diagnosis of breast cancer originally presented to a physician with a self-discovered breast mass. Abnormal physical findings exclusive of breast masses were present in a smaller percentage of patients: 5.9% (15 of 273) presented with bleeding or nipple discharge, 3.5% (9 of 273) presented with palpable axillary nodes only, and only 16% (41 of 273) presented with no physical findings. Summing up these figures, 81.3% (208 of 273) of patients presented with a physical finding compatible with breast cancer. In these litigated cases, only 72.9% (199 of 273) of patients received a mammogram, only 19.8% (54 of 273) underwent a fine-needle biopsy or aspiration, and only 2.9% (8 of 273) received an ultrasound examination. These studies show that a physical abnormality was detected and was documented by physicians on initial presentation in more than three-fourths of patients in whom the diagnosis of breast cancer was delayed.

Unfortunately, the physical abnormalities detected initially in patients with misdiagnosed breast cancer are misinterpreted as benign disease, largely because further workups of these breast abnormalities are either inadequate (relying solely on mammography) or are not performed at all. From medicolegal studies as noted, Kern suggests that isolated, unilateral masses of the breast in women older than age 25, which, on ultrasound evaluation are either solid or are not simple cysts, receive a cytologic or histologic diagnosis (with FNA biopsy, core biopsy, or open excisional biopsy). Such lesions cannot be accurately diagnosed based on visual observation, physical examination, or mammography alone. Even ultrasonography without needle aspiration or biopsy has been accompanied by breast cancer malpractice litigation. In the 2013 PIAA claims study, 4% of cases (87 of 2157) involved diagnostic ultrasound that incorrectly diagnosed a malignant breast lesion as benign.

Unfortunately, before the definitive diagnosis of breast cancer is made in misdiagnosed patients, a benign label is applied to their breast condition, without attempts to obtain a histologic diagnosis. In 1992 Kern reported the prediagnostic labels for 29 cases of misdiagnosed breast cancer. The benign labels were as follows: fibrocystic disease was diagnosed in nine cases, a simple or premenstrual cyst was diagnosed in four cases, abnormal milk gland or galactocele was diagnosed in four cases, mastitis was diagnosed in four cases, a “hormonal” mass was diagnosed in four cases, and an intraductal papilloma was diagnosed in four cases. None of these diagnoses were confirmed by the results of biopsy.

Other studies have confirmed that palpable breast lesions presenting as isolated breast masses are commonly misdiagnosed. Nichols and coworkers, in a study of the National Health Service and breast cancer evaluation, reported that 25 of 57 women with discrete lumps were not referred immediately for evaluation. Many errors are related to the initial inability of a physician to palpate a mass detected by the patient. Deschenes and colleagues reported the high frequency of mislabeling of breast cancers in middle-aged women as benign fibroadenomas. Reintgen and associates studied the threshold of physical detection of breast cancers. From a study of 509 breast cancers at a university breast clinic, they determined the following: (1) the threshold of clinically detected breast cancer is 5 mm, (2) the median detection limit (50% of cancers detected) occurs at 11 mm, and (3) experienced clinicians do not detect more than 80% of breast cancers until the cancer is larger than 16 mm. Because the absolute threshold of detection of breast cancer by patients has never been specifically evaluated, one explanation for physician error in physical examination is simply that patients can detect breast masses at smaller sizes than physicians are able to detect.

False-Negative Mammogram.

The role of diagnostic mammography in women with symptomatic breast disease is a subject of controversy because it has been linked to the creation of diagnostic delays by physicians. This chapter does not address the issue of screening mammography in asymptomatic women, which has been shown through a variety of clinical studies to improve survival in women older than 50 years and perhaps those younger as well. Instead, this section addresses the question of failure to image symptomatic or palpable breast cancers.

Errors in reading mammograms include technical errors in 5%, observer errors in 30%, and nonimaging of breast tumors because of dense or dysplastic breast parenchyma. Nonimaging because of dense or dysplastic breast parenchyma is an age-related phenomenon and the greatest cause of mammographically associated delays in diagnosis. In most cases, diagnostic delays in women with symptomatic breast cancer are a result of false reassurance to physicians that the mammogram does not show breast cancer (i.e., false-negative mammography). Although the threshold size for detection of breast cancer (the minimum size required to consistently see the lesion) is thought to be approximately 2.3 to 2.6 mm, this applies to women with optimal breast tissue for imaging, which generally occurs in women older than 50 years of age. For women younger than 50 years of age, the threshold size of tumor visualization may be considerably greater; it may not be reached until 2 cm or greater, particularly in the youngest of women. Thus despite the presence of an obvious breast mass, the mammogram may show nothing suspicious. In such women, the cancer may have grown to a size allowing metastasis long before it can be imaged with modern mammography. By the time a tumor has reached only 2 mm in size, it contains 4 million cells and has undergone 22 net cell doublings. Tumor angiogenesis, a mandatory process before metastases can reach the systemic circulation, is thought to occur much earlier, at 13 net cell doublings or 0.3 mm in size. Tumor size alone, however, is not the sole determinant of metastases. The role of histologic determinants of prognosis and the future role of molecular genetic determinants of metastases remain central to any discussion regarding the timing of metastatic spread of disease. As yet, our understanding of the interaction between tumor growth, local nodal spread, and systemic spread of metastases is incomplete.

The high frequency of false-negative mammograms in middle-aged women with breast masses is unappreciated by many physicians. Although the false-negative rate for mammography is generally reported as being 7% to 20%, this figure applies to women older than 50 years of age; the actual false-negative rate increases greatly in younger women. For example, the false-negative rate of mammography approaches 80% in Kern’s studies. Other medicolegal studies have shown similar high false-negative rates of mammography. In both the 1995 and more recent 2002 PIAA studies of breast cancer lawsuits, 70% to 79% of diagnostic mammograms were falsely read as negative (or less commonly, equivocal results). Thus a breast mass was documented by physicians on initial presentation in almost three-fourths of patients. However, evaluation by physicians rarely proceeded beyond a negative mammogram, resulting in the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer.

In another study of women younger than 30 years of age with an isolated breast mass, 74% of these masses did not produce an image on mammography. In the Breast Cancer Detection and Demonstration Project involving 280,000 women, mammographic results were falsely negative in 36% of patients 40 years of age compared with 9% of women 75 years of age. Woods and coworkers reported that the average age of those with palpable breast lesions and false-negative mammograms was 44 years. This was significantly less than the average age of those with positive mammograms of 57 years. Mann and associates reviewed 36 women with palpable breast cancer and false-negative mammographic results. The average age of patients was 45 years. The subsequent delays in diagnosis ranged from 3 to 24 months. They noted that 52% of women younger than 45 years had normal mammograms despite a malignant breast mass. Bennett and colleagues reported a false-negative mammography rate in 227 women with symptomatic breast cancer of 24% (8 of 33 cancers). The reported delay caused by false-negative mammography was 8 months. Max and Klamer noted that 52% of mammograms were falsely negative in women younger than 35 years of age who had palpable breast cancers. Walker and Langlands and Walker, Gebski, and Langlands noted a false-negative rate of 30.7% in a group of 230 women with a median age of 50 years. The false-negative report led to a mean treatment delay of 12.7 months, ranging between 3 and 60 months. Joensuu and coworkers reported that the false-negative rate in women younger than 50 was 35% in a study of 306 women with invasive cancer. This was significantly different than the rate of 13% in women older than 50 years of age ( p < .0001). In those with a false-negative mammogram, 30% had delays of 6 months or more. For those with true-positive mammograms, no patients were delayed 6 months.

Others have reported that false-negative mammography is common in middle-aged women. Thus the woman with a breast mass who is 45 years of age or younger faces two perils in the diagnostic process. First, physicians assume that she is too young to have breast cancer. Second, given the difficulties inherent in imaging premenopausal breast tissue, mammograms may not provide useful diagnostic information about the mass. Kern reported that of the 44% of patients (20 of 45) who underwent mammography, studies were negative in 80% (16 of 20). Only one patient (2%) underwent FNA of a breast mass, which proved to be falsely negative. As in palpable masses, the reason for false-negative mammography is related to the increased breast density of younger women, which makes x-ray penetration more difficult.

The impact of false-negative mammograms on the delay in diagnosis was studied by Burns and colleagues. In a group of 80 women with negative mammograms, 50 (63%) presented with palpable breast masses. The negative mammogram resulted in a delay in diagnosis in this group of 1 month to 5.4 years; it averaged 11 months. Burns and associates pointed out the irony that although women were being urged to learn breast self-examination and more than 80% of breast cancers are found on palpation by the patient herself, false-negative mammography was creating delays in diagnosis after patients presented to a physician with a self-discovered breast mass.

Others have also noted the curious anomaly that the introduction of mammography into clinical practice as a technique for the early detection of asymptomatic breast cancer has resulted in delayed diagnosis because of its widespread use as a diagnostic tool in symptomatic women. Max and Klamer noted, in a study of 120 women with breast cancer with an average age of 31 years (range, 22–35 years), that in 7% of women who contacted a physician immediately after the onset of symptoms, the physician delayed for more than 2 months before recommending biopsy. Locklear and Langlands noted that in a study of 735 women with breast cancer, 13% had false-negative mammograms, resulting in a diagnostic delay of 11.2 months, ranging from 2.5 to 48 months. Age played a significant role in the rate of false-negative mammographic results. Of the women with false-negative mammographic results, 73% were premenopausal, compared with 38% in the no-delay group.

Others have reported that delays in diagnosis occur in almost 50% of premenopausal women because of false-negative mammography. Although some authors have argued that it would take 80 biopsies of benign palpable lesions in this age group to detect four misdiagnosed breast cancers, Kern believes it is unlikely that patients will accept these probabilistic arguments as a reason not to seek a timely diagnosis of mammographic abnormalities. Minimally invasive breast biopsy techniques, such as FNA biopsy or ultrasound-guided core biopsy, are accompanied by extremely low morbidity rates. The safety of these approaches negates any arguments suggesting that these types of biopsies are “unnecessary surgery.” Katz and coworkers reported that in a series of women in British Columbia and Washington State, the preponderance of diagnostic delays was the result of nonsuspicious, false-negative mammograms. Tennvall and colleagues demonstrated that women with both negative or inconclusive mammograms and negative FNA cytology of palpable breast masses were found to be 11 years younger than the group with combined positive findings. In these young patients, negative cytology and negative mammography led to extended diagnostic delays. Delays in diagnosis, even when the end result is benign, can have significant adverse psychological impact on patients.

The high rate of false-negative mammograms in young women has led some to recommend that diagnostic mammography simply not be used in symptomatic women. Mahoney and Csima studied 302 women with breast cancer and found 87%, or 263 women, had false-negative mammograms. Mahoney noted that mammography is most productive when used as a routine screening study in women older than 50 years of age with clinically normal breasts. These workers noted that 53% of palpable breast cancers did not image in women younger than 45 years of age. The mean age for a false-negative mammogram with a palpable breast cancer was 49.3 years; for a positive mammogram with a palpable cancer, it was 58 years. The mean size for a negative mammogram was 2.1 cm, and for a positive mammogram, it was 3.3 cm. Mahoney recommended three rules related to mammography and breast cancer: (1) use mammography as a screening study in older women with normal breasts; (2) never delay biopsy of a breast lump that is solid on aspiration because of a negative mammogram; and (3) mammography in symptomatic women younger than 35 years of age is unrewarding and should not be used.

Barratt and coworkers used a telephone survey to evaluate women’s expectations of mammography in a subpopulation of women (n = 115) completing a larger, comprehensive breast health survey (n = 2935). Unrealistically high expectations of the ability of mammography to detect disease were present in these women, many of whom favored litigation despite the known, reported false-negative rate for mammography. Inadequate education on the true ability of mammography to detect disease in a variety of settings and patient age groups is one important contributor to the malpractice problem in breast cancer. Chamot and Perneger came to similar conclusions, suggesting that the patient’s lack of understanding of the ability of mammography to detect breast cancer is one key factor in litigation. The widespread use of mammography in symptomatic breast cancer comes at a high cost, as noted previously. The indemnity cost of misdiagnosed breast cancer, based on errors in mammographic readings, averaged about $230,000 per case in 2005 and had grown to more than $300,000 in 2015.

Langlands and Tiver reviewed 1433 consecutive patients undergoing mammography and found a false-negative rate in those with palpable abnormalities of 30%. In 16% of these patients, the false reassurance of mammography directly contributed to diagnostic delays ranging from 2 to 24 months. Langlands and Tiver used a statistical argument to show that the use of diagnostic mammography in women with a palpable breast lesion of any age is inappropriate for two reasons: (1) the low probability of imaging the lesion in the young and (2) the inability to make definitive statements about a cancer diagnosis without a confirmatory biopsy, even in older women. In this series, diagnostic delays as a result of false-negative mammography ranged from 2 months to 3 years.

Some authors have disputed the rate of false-negative mammography. Cregan and coworkers studied the extent of delay in 219 women and found that only 11% of women had false-negative mammography. This led to a delay in diagnosis of 1 to 3 months in 10% of women (3 of 32 cases). These authors pointed to the value of mammography in women as young as 25 years of age (in whom early signs of familial cancer may be detected, such as irregular, clustered microcalcifications), especially in those with a family history of breast cancer in which early onset is the rule. Bassett and associates argued for a tailored mammographic examination in women younger than 35 years of age with localized breast symptoms, particularly those without a palpable lump. In a study of 1016 women younger than 35 years of age with breast cancer, Bassett evaluated a group of 454 women with palpable breast masses. He noted that two women sustained delays of 4 months and 10 months because mammograms did not image palpable lesions of 2 cm and 1.5 cm; these lesions were labeled as fibroadenomas without biopsy confirmation. In terms of nonlump symptoms in a group of 53 patients, one 34-year-old patient with localized breast tenderness was diagnosed with architectural distortion on tailored mammogram, leading to an immediate breast biopsy and cancer diagnosis. One 26-year-old patient with unilateral discharge had a negative mammogram and sustained a delay of 6 weeks before a biopsy was performed. On the basis of these results, Bassett reminded readers that a negative mammogram should not preclude biopsy of a palpable, solid mass. Blichert-Toft and colleagues in a series of 167 patients in a Danish breast clinic, showed that immediate workup of vague symptoms or unilateral palpable findings by needle aspiration biopsy or open biopsy prevented delayed diagnosis, despite false-negative mammograms in eight patients (5%).

Screening mammograms that show highly suspicious lesions in younger women with no palpable breast abnormalities may diagnose breast cancer with great accuracy and with a detection rate as high as 40%. However, when mammograms are read as nondiagnostic, indeterminate, or not suspicious, the rate of missed cancers approaches 5% (6 of 127). Erickson and colleagues showed that 2% of patients observed because of an indeterminate mammogram, without the presence of symptoms, were later diagnosed as having cancer. Of the 114 women in the study group, 3 sustained delays of 3, 12, and 15 months, respectively. Nonetheless, with an average delay of 10 months, patients had no progression in stage, as measured by the rate of positive axillary nodes.

The introduction of three-dimensional mammography and other computerized techniques to enhance mammographic imaging has resulted in concerns that mammograms read without these advanced technologies might expose radiologists to a greater degree of malpractice risk. However, until such time as advanced methods to computerized or enhance breast imaging is the generally accepted standard of care, the impact of these techniques in reducing the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer, and subsequent litigation, remains unknown.

Delays Related to Pregnancy-Associated (Gestational) Breast Cancer

Diagnostic delays in gestational breast cancer are frequent for two reasons. First, the incidence in clinical practice is low, leading to inexperience on the part of physicians. Second, the physiologic changes in the gestational breast are similar to those of malignancy.

Although only 1% to 2% of cases of breast cancer overall are diagnosed during pregnancy, the number of pregnancies that are complicated by breast cancer ranges from 0.03% to 3.1% for women in the childbearing age group of 15 to 45 years. Others have estimated the rate of gestational breast cancer to be between 1 case per 1360 deliveries and 1 case per 6200 deliveries. Donegan has provided a table of age-specific frequency that demonstrates a rate for women in the United States during 1970 as having gestational breast cancer ranging between 0.25 to 2 cases per 100,000. As cited by Scott-Connor and coworkers, other reviewers have placed this rate at 10 to 39 gestational breast cancers per 100,000 women. Because there are approximately 3.4 million live births in the United States annually, the author estimates the number of gestational breast cancers to range from 350 to 1400 cases yearly. The average obstetrician manages between 150 and 250 pregnant women yearly, and thus the chance that an individual obstetrician will see gestational breast cancer in any one practice is extremely low. A large multiphysician group that delivers more than 3000 infants yearly might expect to see one to three cases of gestational breast cancer each year. Because of its rarity, it is important for clinicians managing pregnant women to understand the potential for pregnancy and breast cancer. Special attention should be given to high-risk groups, such as women in breast cancer–prone families, who may develop gestational breast cancer.

In the 1950s, McWhirter pointed out that pregnant patients were often given wrong advice when presenting with a breast mass. Instead of being advised to undergo diagnostic biopsy, they were often asked to do what McWhirter believed were potentially harmful maneuvers such as massaging the lump or applying a poultice. As noted by Bottles and Taylor, delayed diagnosis in gestational pregnancy presents a paradox because pregnant patients are seen many more times than usual by physicians compared with nonpregnant patients. In 1958 Treaves and Holleb reported from a study of 108 patients with gestational breast cancer that the median delay in diagnosis in pregnant women was 4 months, which was twice as long as that for nonpregnant women. In one report, 50% of gestational breast cancers were not diagnosed until 3 weeks after delivery. Petrek has shown that fewer than 20% of patients with gestational breast cancer were diagnosed during pregnancy. Others have shown that the duration of symptomatic breast cancer before diagnosis in pregnant women ranges between 2 and 15 months. Byrd and coworkers noted that two-thirds of women with a breast cancer first detected during pregnancy were advised to defer biopsy until after delivery, on the incorrect assumption that their breast masses were benign. Supporting this finding, Donegan has shown that only one-third of pregnant women are admitted to the hospital for definite treatment of breast cancer within 6 months of discovery of a breast mass. Donegan also determined that the delay in diagnosis of breast cancer in pregnant women averages 13 months. Deemarsky and Semiglazov confirmed that the delay in diagnosis of breast cancer in pregnant women ranges between 11 and 15 months. Gallenberg and Loprinzi noted that delays in diagnosis of breast cancer generally exceed 5 months. Treves and Holleb reported that physicians watched an abnormal breast mass for an average of 2 months longer than they normally would in nonpregnant patients.

Given the frequent diagnostic delays until final diagnosis, gestational breast cancer is often in advanced and late stages. This finding of late disease has been attributed to delay in diagnosis, largely by physicians. Zinns concluded that delay in diagnosis is “the most significant, controllable factor in the patient’s prognosis.” Westberg stated that “it would seem thus that pregnancy has no very great effect on prognosis of breast cancer, apart from the fact that patients delay in consulting a physician, and the physician is inclined to postpone surgery.” Many other authors believe that delay in diagnosis is the sole factor accounting for the diminished survival of pregnant patients with breast cancer because stage-for-stage survival is equivalent in the two groups. In contrast, other authors cite the unfavorable biological factors favoring rapid tumor growth and early dissemination in gestational breast cancer, such as the high nutrient hormone levels and relatively low host immunity during pregnancy.

Barnavon and Wallack used a comprehensive review of the world literature to demonstrate that regardless of diagnostic delay, pregnant patients with breast cancer fare worse overall than their nonpregnant, premenopausal counterparts. Typically, gestational breast cancers are large, with the median size in one study of 3.5 cm. Gestational breast cancers are often associated with positive axillary nodes; up to 70% to 89% of patients are node positive. Byrd and colleagues reported that pregnant patients with involved axillary lymph nodes had a longer delay from first symptom to definite diagnosis, nearly twice that of nonpregnant patients (7.4 vs. 3.1 months). Guinee and coworkers have shown that the odds ratio of a pregnant patient dying of breast cancer is threefold that of a woman with breast cancer who has never been pregnant.

Given the high risk of misdiagnosis of gestational breast cancer, the use of fine-needle biopsy has been advocated to diagnose any dominant or suspicious breast abnormality in the pregnant or lactating woman, particularly when the patient believes the abnormality appears or feels different than usual. Great caution should be used in interpreting FNA biopsy results. Any cytologic atypia should be followed by open breast biopsy because atypical changes in breast tissue are not caused by pregnancy and suggest the presence of malignant disease. Kern advocates a core-cutting needle biopsy to decrease the rate of equivocal or misleading cytology seen with a fine-needle approach. Open breast biopsy is safe when performed with the patient under local anesthesia, and it should not be delayed in the pregnant woman with an isolated, dominant mass that has either clinically suspicious characteristics or has undergone needle aspiration and been found to contain cytologic atypia, an indeterminate diagnosis, or frank cancer.

Delays in Diagnosis Related to Male Breast Cancer

Delays in the diagnosis of male breast cancer are common. In males, more advanced stages of disease are present at final diagnosis, and this is hypothesized to be the result of a combination of delay in diagnosis and anatomic factors. In males, there is less intervening tissue between the breast, skin, and chest wall. Bounds and colleagues noted that only 1% of cases of breast cancer occur in males. Of all male cancers, only 0.2% take the form of breast cancer. The incidence of male breast carcinoma in the United States is 1 per 100,000, nearly 150 to 200 times less frequent than breast cancer in females. The median age of patients has been reported to vary between 63 years and 70 years. Because of its infrequent nature and presentation in elderly patients who often exhibit typical senile gynecomastia, delays in diagnosis by physicians (and delayed recognition of symptoms by patients) are common. This is believed to be one factor accounting for the percentage of patients with positive axillary nodes on diagnosis (50%) and metastatic disease (80%). Stierer and colleagues documented that the delay in diagnosis from the first onset of symptoms and the onset of therapy ranged from 1 week to 84 months, with a median delay of 3 months. Tumor size correlated with the median delay; small T1 tumors had a median delay of 2 months, whereas large T3 and T4 tumors had a median delay of 10 months. The investigators believe that diagnostic delays are so common that they establish proof that early diagnosis is virtually never reached in male breast cancer.

Delays in Diagnosis Related to False-Negative Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy

FNA biopsy plays an important role in the rapid diagnosis of palpable breast masses and other palpable abnormalities of the breast. Svensson and associates demonstrated the ability of FNA biopsy to diagnose malignant tumors in women as young as 20 years of age, an age generally not recognized as being prone to breast cancer development. In a series of more than 3000 FNA biopsies, Gupta evaluated 691 women younger than 30 years of age. The false-negative FNA rate was 0.4% (3 of 691).