Abstract

Attention to issues related to breast cancer survivorship is important to optimize oncologic outcomes and quality of life. Patients, cancer care providers, and primary care providers must work collaboratively to address these issues. Late and long-term effects can be related to surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy. Common survivorship issues include fatigue, cognitive changes, cardiac dysfunction, sexuality, psychosocial issues, weight management, pain, fertility, and menopausal symptoms. Genetic and genomic testing will inform, stratify risk, and guide treatment options and management for appropriate personalized follow-up. Survivorship care plans are now mandated by national accrediting organizations, but require care models that have the ability to develop and deliver this tool and the necessary services to meet the needs of each survivor. This chapter aims to describe the scope of survivorship issues with advice on management of specific issues and stresses the importance of the creation of a multidisciplinary shared care practice model.

Keywords

cancer survivorship, survivorship treatment summary, survivorship program, survivorship care plan, and survivorship care

Background

The diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer includes imaging, biomarker-driven targeted therapies, and genetic and genomic testing used to stratify risk and response to treatment. The treatment plan requires personalization, and the same degree of personalization is now suggested for patients who have completed therapy to optimize quality of life and oncologic outcomes. An individual is considered a cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis through the balance of his or her life. Family, friends, and caregivers are also affected by an individual’s treatment for breast cancer. Standards for survivorship care should include prevention of new and recurrent cancers and other late effects, surveillance for cancer spread, recurrence or second cancers, assessment of late psychosocial and physical effects, intervention for consequences of cancer treatment, and coordination of care between primary care providers and specialists to ensure that all of the survivor’s health needs are met. National mandates are pushing the delivery of a treatment summary and long-term care plan after treatment, which requires the ability to develop and deliver this tool and the necessary health care delivery model to manage the unique needs of each cancer survivor. Navigation and care coordination across the continuum to assess needs, meet those needs, and outline and manage expectations are essential. Plans for survivorship care require transparency and clear communication among the cancer team, the patient, and the primary care provider. Necessary components of care include identification and management of late and long-term effects of breast cancer and its treatment and understanding cancer risk and management strategies. A process must be in place that meets those needs and monitors outcomes. Survivorship care is a specific approach that addresses patients’ long-term needs according to evidence-based American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network has also released recommendations for survivorship care. Ideally this care is delivered in a collaborative, patient-centered model among multiple subspecialties. Because a majority of cancer care occurs in a community setting, challenges to delivery of care include successful navigation, communication, and clear delegation of responsibilities by providers, survivors and community support organizations, and sufficient time and resources to deliver survivorship care. Having access to guidelines and recommendations promotes the delivery of patient-centered, coordinated care, and requires ongoing evaluation of outcomes.

Identification and Management of Late and Long-Term Effects of Breast Cancer and Treatment

Late and long-term effects of breast cancer and treatment include both physical and psychosocial issues. Later effects can appear months or even years after treatment ( Box 85.1 ).

Chemotherapy

- •

Cardiotoxicity/heart problems

- •

Cataracts/vision changes

- •

Cognitive impairment

- •

Endocrine dysfunction

- •

Early menopause/menopausal symptoms

- •

Increased risk of recurrence and second cancers

- •

Infertility

- •

Liver problems

- •

Lung problems

- •

Mouth/jaw problems

- •

Nerve damage

- •

Osteoporosis

- •

Pain

- •

Reduced lung capacity

Radiation Therapy

- •

Cataracts

- •

Cavities and tooth decay

- •

Fatigue

- •

Heart and vascular problems

- •

Hypothyroidism

- •

Increased risk of other cancers

- •

Infertility

- •

Intestinal problems

- •

Lung disease

- •

Lymphedema

- •

Memory problems

- •

Osteoporosis

- •

Pain

- •

Skin changes

Surgery

- •

Disfigurement and body image concerns

- •

Fatigue

- •

Lymphedema

- •

Mobility problems

- •

Pain

Physical effects include pain, fatigue, sleep disorders, weight gain, pulmonary toxicity, bone loss, cardiac toxicity, sexual dysfunction, menopausal symptoms, and fertility issues. Factors that increase the risk of late effects include age at diagnosis (older and younger patients are at highest risk), family history, type and cumulative dose of treatment, and lifestyle factors (e.g., tobacco use, alcohol use, weight, and physical activity). Patient-reported outcomes addressing late and long-term effects of cancer and its treatment should be part of continuity of care for breast cancer survivors. This chapter targets some of the major issues that breast cancer survivors face.

Fatigue

Breast cancer and its treatment are associated with cancer-related fatigue (CRF), which is the most common, and possibly most disabling, symptom of breast cancer survivors. CRF is different from fatigue in otherwise healthy individuals, whose fatigue can be resolved with rest.

CRF is defined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) as “a distressing, persistent, subjective sense of physical, emotional and/or cognitive tiredness, related to cancer or cancer treatment that is not proportional to recent activity and interferes with usual functioning.” Approximately 25% to 30% of breast cancer survivors experience persistent fatigue for 1 or more years after the completion of cancer treatment, and it is rarely addressed to the satisfaction of the survivor. Risk for severe fatigue increased with higher stage of disease, and risk decreased in breast cancer survivors who reported having a partner and in those who did not receive chemotherapy, but only surgery with or without radiation CRF can affect daily activities, work performance, and overall quality of life.

Breast cancer survivors may worry that fatigue might be a sign of disease progression, but they need to be reassured that fatigue is common both during and after treatment. Understanding the onset and presentation of fatigue is vital to establish the pattern, duration, and intensity. In addition, a comprehensive assessment should include pain, emotional distress (depression and anxiety), anemia, sleep disturbance, lifestyle (diet and exercise, alcohol consumption), review of medications, and comorbidities. One common comorbid condition found in breast cancer survivors that can result in fatigue is hypothyroidism, especially in older breast cancer survivors. Thyroid function should be monitored on a regular basis regardless of treatment modalities.

Numerous strategies have been evaluated to address cancer-related fatigue. Box 85.2 outlines management strategies for CRF.

- I.

Patient and family education: providing information and reassurance regarding cancer-related fatigue (CRF) both during and after treatment

- a.

Standard screening

- b.

Survivor and family education, counseling, and intervention as needed

- c.

Self-monitoring

- a.

- II.

Nonpharmacologic strategies for managing CRF

- a.

Energy conservation and activity management (ECAM)—modest benefit

- b.

Prioritize activities: structure and routine, delegate activities, focus on time of day, postpone nonessential activities, pace and intensity, limit naps to not interfere with sleep quality

- c.

Physical exercise and movement: address limitations due to stage of disease, surgical management, and comorbid conditions

- i.

Meta-analyses found relief with exercise

- ii.

Encourage initiation or maintaining exercise program as appropriate for level of activity and with a focus on safety:

- 1.

Use cancer-specific exercise programs or meet with a cancer-certified trainer

- 2.

American College of Sports Medicine and the American Cancer Society recommend 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity

- 3.

Walking, jogging, swimming, yoga, light resistance training

- 1.

- iii.

Consider cancer rehabilitation

- iv.

Massage therapy by a cancer-specific trained therapist

- i.

- d.

Psychosocial interventions

- i.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

- 1.

Cognitive restructuring and distraction techniques

- 1.

- ii.

Manage anxiety and depression

- i.

- e.

Nutrition

- f.

Sleep: address sleep hygiene and consider cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) or bright white light therapy

- a.

- III.

Pharmacologic strategies for managing CRF

- a.

Treat pain, anemia, thyroid dysfunction, sleep

- b.

Manage anxiety and depression

- i.

Antidepressants

- i.

- c.

Psychostimulants

- a.

Cognition

Breast cancer– and cancer treatment–related effects on cognitive function are common concerns for breast cancer survivors. A number of factors may contribute to the development and experience of cognitive impairment for breast cancer survivors, including age, education level, menopausal status, psychological distress, type and dose of chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, time since radiation therapy, and time since general anesthesia. The majority of breast cancer survivors report some degree of cognitive dysfunction after completion of chemotherapy. A subset of cancer survivors (17%–34%) who receive chemotherapy appear to experience long-term cognitive impairment. Long-term cognitive sequelae have been documented as late as 20 years after the completion of therapy for women with breast cancer.

Breast cancer survivors describe cognitive changes such as forgetfulness, absentmindedness, and an inability to focus when performing daily tasks. Complaints also include difficulty with short-term memory, word-finding, reading comprehension, driving/directional sense, and concentration. A variety of mechanisms have been proposed for the development of cognitive impairment, including cytokine-induced inflammatory response, deficits in DNA repair mechanisms, genetic predisposition, chemotherapy-induced anemia, chemotherapy-induced menopause, and injury to neural progenitor cells involved in white matter integrity and adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Cognitive impairment experienced before receiving treatment for cancer has been hypothesized to be due to the release of cytokines associated with tissue damage from the tumor. Cognitive impairment perceived before treatment for breast cancer may also be influenced by the impact of the cancer diagnosis on mood states (such as anxiety and depression) and the resultant effects on the capacity to direct attention. Results of previous research also suggest relationships between perceived cognitive impairment (PCI) and fatigue, sleep disturbance, and neuropathy for survivors who have received chemotherapy.

The potential role of inflammatory cytokines as a causal mechanism for cancer and cancer treatment-related cognitive complaints is intriguing. Chronic inflammation is associated with a negative effect on the neural systems involved in cognition and memory and has been linked to obesity. Obesity is a risk factor for breast cancer, disease recurrence, and poor prognosis. Weight gain is common for women receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer. The chronic inflammatory state associated with obesity may contribute to the risk of cognitive changes in this population as has been seen preclinically and in populations with other disorders such as the metabolic syndrome, which is linked to cardiovascular risk factors.

Exercise is a strategy employed by some breast cancer survivors to attempt to decrease PCI, and evidence is building in support of exercise as an intervention for cancer-associated cognitive complaints. Numerous organizations have published guidelines and recommend regular exercise and strength training for cancer survivors and recently added routine exercise as one of the general strategies for management of cancer-associated cognitive dysfunction.

Challenges in supporting the right types of interventions have to do with study design and assessment tools used in previous research. There is modest correlation between objective and subjective testing. The capacity for comprehensive testing is limited in most cancer care facilities, and no sensitive brief screening tool for cancer-related dysfunction has been accepted as the gold standard. Education and validation of the survivor-reported cognitive dysfunction is a first step. Survivors should be reassured that cancer-associated cognitive dysfunction is common but usually transient.

On the basis of clinical assessment, management strategies to address cognitive dysfunction include the following:

- •

Support engaging in enhanced organizational skills including the use of lists, calendaring, smart devices, GPS, and consistent behaviors such as putting keys in the same place.

- •

Reinforce the need to be realistic about what can be accomplished during and after treatment. Trying to maintain pretreatment levels of activity might not be realistic and can be frustrating to the survivor.

- •

Encourage behavioral techniques to reduce stress and for relaxation.

- •

Manage anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, fatigue, pain, and other comorbidities.

- •

Encourage lifestyle modification including increasing exercise, healthy diet, and limiting alcohol consumption.

Formal neuropsychological evaluation and referral for cognitive rehabilitation are recommended to address unresolved cognitive dysfunction. Cognitive rehabilitation is a behavioral intervention that strives to train or retrain cognitive functions or to compensate for specific cognitive deficits. This emerging area of clinical research explores how to optimally guide survivors on how to cope with cognitive complaints and dysfunction. Outcomes of cognitive rehabilitation research support objective improvements in overall cognitive function, visuospatial constructional performance, and delayed memory and subjective improvements of cognitive impairment and psychosocial distress. If these strategies are not effective, then psychostimulants can be considered under the direction of a licensed practitioner.

Since the establishment of the International Cognition and Cancer Task Force in 2003, there has been a multidisciplinary consensus of neuropsychologists, clinical and experimental psychologists, neuroscientists, imaging experts, physicians, and patient advocates who participate in regular workshops on cognition and cancer. This group strives to advance our understanding of the impact of cancer and cancer-related treatment on cognitive and behavioral functioning in adults with noncentral nervous system cancers. Ongoing investigation to further explore the mechanisms of action, validate clinically meaningful screening, and understand the effects of hormone therapy will enhance the current understanding and management of a common issue experienced by breast cancer survivors.

Cardiac Dysfunction

As a significant number of breast cancer survivors live with and through their disease, attention to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality is an essential part of breast survivorship care. In long-term breast cancer survivors over age 66 with early-stage disease, cardiovascular disease (CVD), is the most common cause of death. In all breast cancer survivors receiving adjuvant treatment, cardiovascular disease is the third most common cause of mortality after breast cancer recurrence and second primary tumor. A recent comparison between women with and without a diagnosis of breast cancer revealed that breast cancer survivors were at greater CVD-related mortality, and this risk manifested approximately 7 years after diagnosis.

There are a number of established preexisting risk factors for CVD: age, obesity/body mass index, sedentary lifestyle or difficulties with exercise tolerance, comorbid medical conditions (diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, stroke), family history, tobacco use, chronic kidney disease, and poor cardiorespiratory fitness. Thus, many women diagnosed with breast cancer are already at elevated risk for CVD before any treatment, and issues should be addressed before the initiation of treatment. Collecting CVD risk factors during an initial consult and throughout ongoing care is supported by the National Cancer Institute Community Cardiotoxicity Task Force and the International CardiOncology Society. These experts support cardio-oncology as a growing field and promote collaboration between highly specialized professionals and primary care.

Breast Cancer Treatment–Specific Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors

Anthracyclines are agents that directly cause cardiac damage. The likely target are cardiomyocytes, which have a poor antioxidant defense system. It is thought that anthracycline exposure leads to myocyte apoptosis and damage is irreversible, resulting in an increase in CVD-related morbidity and mortality. The incidence of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity is dose dependent and can result in heart failure. Breast cancer survivors who have received treatment that includes anthracycline (e.g., doxorubicin >250 mg/m 2 , >epirubicin 600 mg/m 2 ) should be considered at high risk for developing cardiac dysfunction. Predictors of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity include high doses and symptoms that occur within the first year after the initiation of treatment. The clinical course is often dependent on the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at the end of treatment.

A 10% or greater decrease in LVEF or LVEF less than 50% is considered significant. By this point, permanent damage has likely occurred. Before the introduction of HER2-directed therapies, the incidence of anthracycline-induced cardiac dysfunction (median dose of doxorubicin at 390 mg/m 2 ) had been previously reported to be 2.2%, with rates highest in those receiving anthracycline-based regimens combined with a taxane. In a retrospective cohort study of 12,500 women diagnosed with breast cancer, 20% to 25% exhibited amplification of HER2 and received trastuzumab, and approximately 30% received an anthracycline-based regimen. After adjusting for age, comorbidities, stage, year of diagnosis, radiation therapy, the cumulative incidence of heart failure or cardiomyopathy at 5 years after treatment was 4.5% for anthracyclines, 12.1% for trastuzumab and 20.1% receiving the combination. Survivors who received a combination therapy including an anthracycline and trastuzumab were generally younger, healthier, and presumably at lower risk for CVD.

Another striking finding is the high rate of subclinical dysfunction among breast cancer survivors. Kalyanaraman and coworkers found that doxorubicin-induced subclinical cardiomyopathy affects approximately one in four breast cancer survivors. With the increase in disease-free survival in breast cancer survivors, many may already have or will acquire traditional CVD risk factors. These findings highlight the long-term need to monitor breast cancer survivors.

Trastuzumab, a HER2-directed targeted therapy, indirectly causes cardiac damage that will typically have a significant delay of months to years from the time of treatment until cardiac dysfunction is detectable. Exposure to trastuzumab can have a cumulative dose-dependent effect that is often reversible. This result can be an independent exposure or a result of the combined toxicity with an anthracycline.

Radiation therapy has long been a concern for cardiac dysfunction, especially if treating a left-sided breast cancer. Radiation exposure is associated with risk of ischemic heart disease in breast cancer survivors based on the dose and lag time of up to 20 years. More recent findings using modern techniques of computed tomographic guidance and respiratory gating for left-sided breast cancer result in lower cardiac doses. Unfortunately, the long-term effects of low-dose radiation are unclear.

Exercise has been shown to provide benefit to those with and without CVD. Exercise has been studied extensively in breast cancer survivors but has not yet been shown to mitigate cardiotoxicity. Organizations including the American Cancer Society and the American College of Sports Medicine recommend 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity exercise with the inclusion of resistance training.

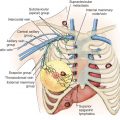

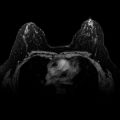

Current practice guidelines are limited in the long-term management of cardiac dysfunction in breast cancer survivors. The assessment of risk will be aided by the development of risk prediction models that will stratify breast cancer survivors. By categorizing breast cancer survivors into high or moderate risk, appropriate follow-up can be recommended. The types of ongoing surveillance are under review. The inclusion of serum biomarkers, cardiac imaging with echo/multigated acquisition scan or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the use of strain (which represents the magnitude and rate of myocardial deformation), and referral to a cardio-oncologist will all be part of follow-up guidelines.

Efforts should be made to identify risk factors and interventions that can be employed during this brief window to reduce the excess burden of CVD in this vulnerable population. Clinicians need information to screen high-risk patients and prevent cancer treatment–related cardiotoxicity, to balance effective cancer treatment and cardiac risk assessment in treatment decision-making, and to manage long-term cardiac risks.

Sexual Health, Body Image, and Relationship Issues

Sexual quality of life is an important issue, and sexuality ranks high on surveys of unmet survivorship needs. Issues are most commonly due to the toxicities of cancer treatment. Sexual problems after cancer are linked with menopause, depressed mood, poor quality of life, and decreased intimacy. The impact of breast surgery on body image and self-esteem, both important in sexual health, are well characterized. Chemotherapy may result in side effects (fatigue, nausea, etc.) that may limit a woman’s sexual interest or ability to become aroused. Chemotherapy-induced menopause may lead to vasomotor symptoms, urogenital symptoms (vaginal dryness), atrophy-related urinary symptoms, and decreased libido. Hormonal therapy to treat breast cancer also affects sexuality. Although both tamoxifen and the aromatase inhibitors may affect sexual function, the risk may be higher with the aromatase inhibitors with regard to lubrication issues, dyspareunia, and global dissatisfaction with one’s sex life. One recent cross-sectional survey assessing 129 women during the first 2 years of aromatase inhibitor therapy showed that 93% scored as dysfunctional on the Female Sexual Function Index and 75% of dysfunctional women were distressed about their sexual problems. Twenty-four percent stopped having sex, and 15.5% stopped aromatase inhibitor therapy. Women who receive radiation therapy may experience cosmetically detrimental skin changes affecting body image.

Women should be asked about sexual function at regular intervals. Patients are not likely to bring up sexual concerns spontaneously. Providers should ensure that engaging patients directly in conversations regarding sexual health address concerns. Direct conversations are a sign for patients that the provider is open to discussing sexual issues, and this might enable patients to raise these issues in the future should they arise. The NCCN Survivorship Guidelines Version 2.2015 recommends a brief sexual symptom checklist for women as a primary screening tool. Past and present sexual activity should be reviewed including a discussion about how cancer treatment has affected sexual functioning and intimacy. In addition, treatment-associated infertility should be discussed, if indicated, with appropriate referrals. For a more in-depth evaluation of sexual dysfunction, consider the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), which has been validated in cancer patients and/or the PROMIS sexual function instrument. It is important to remember that complete sexual recovery may not be possible during or after cancer treatment. In creating a care plan, one must build from where the patient is and focus on creating a “new normal,” using the specific concerns of the patient to guide treatment. By highlighting positive changes and new attitudes, many patients will find equally if not more meaningful sexual experiences posttreatment.

When dealing with the multiple stressors that can be associated with a diagnosis of breast cancer, body image can also be a negatively affected. Hair loss, body disfigurement due to surgery or lymphedema, radiation therapy, and weight gain can have profound effects on breast cancer survivors. There also may be partner issues that can affect whether a breast cancer survivor undergoes breast reconstruction. Intimacy is commonly affected.

Recognizing that female sexuality and relationship satisfaction is often driven by psychological and psychosocial influences, Basson elaborated on our understanding by incorporating intimacy as a driver for desire and sexual activity. For couples, Manne and Badr, proposed the Relationship Intimacy Model, which characterizes the recovery from cancer treatment as multifactorial. Beyond instruments aimed to query sexual function, other questionnaires are available to help evaluate other aspects of sexual health including body image, quality of relationships and intimacy within relationships. Of course, the status of the relationship and satisfaction with intimacy for a couple before the breast cancer diagnosis is important in evaluating subsequent concerns.

First-line therapy for addressing sexual health may include gynecologic care (vaginal moisturizers, lubricants, vaginal dilators, vibrators, relaxation techniques, or exercises. Second-line therapy including topical estrogen therapy (if not contraindicated) may be considered if first-line therapies do not adequately provide relief. Encourage ongoing partner communication and identify resources for psychosocial dysfunction with appropriate referrals for psychotherapy or sexual/couples counseling. Vaginal dryness due to antiestrogen therapy commonly leads to dyspareunia. Women may feel disinterested due to fear of pain with intercourse. Vaginal estrogen is an effective treatment for dryness, but concerns exist about detectable increases in serum estrogen levels. A recent study, however, that included 13,000 women with breast cancer found no increase in the recurrence risk in women treated with endocrine therapy whether or not local estrogen therapy was administered. A systematic comprehensive review of minimally absorbed vaginal estrogen products is provided by Pruthi and coworkers. Low-dose vaginal 17-beta estradiol tablets (10 mcg) are associated with a typical estradiol level of 4.6 pcg/mL and a maximum annual delivered dose of 614 mcg. Estring vaginal ring inserted vaginally every 3 months has a typical serum level of 8.0 pcg/mL and an annual delivered dose of 2.74 mg. Prospective long-term safety data are lacking, and the use of estrogen for vaginal atrophy in the breast cancer survivor remains controversial. A prospective trial is underway at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center examining follicle-stimulating hormone and estradiol levels, sexual function and quality of life in breast cancer patients receiving an aromatase inhibitor and 10 mcg of 17-beta estradiol vaginal tablets. A phase III randomized clinical trial of 216 postmenopausal women without breast cancer given dehydroepiandrosterone showed improvement in all domains of sexual function without significantly increasing serum estrogen, testosterone, or androgen levels. A nonhormonal vaginal moisturizer, hyaluronic acid vaginal gel (Hydeal D), was recently studied and showed improvement in vaginal and sexual health issues. Regular sexual activity has also been found to be useful in preventing vaginal atrophy. Survivors should engage in informed decision-making regarding hormone therapy, including coordination with the treating oncologist, discussing the pros and cons, and a summary of data to date.

Vasomotor symptoms include hot flashes and night sweats (which do not always occur at night). Numerous strategies have been evaluated to manage this common complaint in breast cancer survivors. Nonhormonal management strategies that have been reported to provide relief include: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, gabapentin, acupuncture, and exercise (including yoga).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree