(1)

State University of New York at Buffalo Kaleida Health, Buffalo, NY, USA

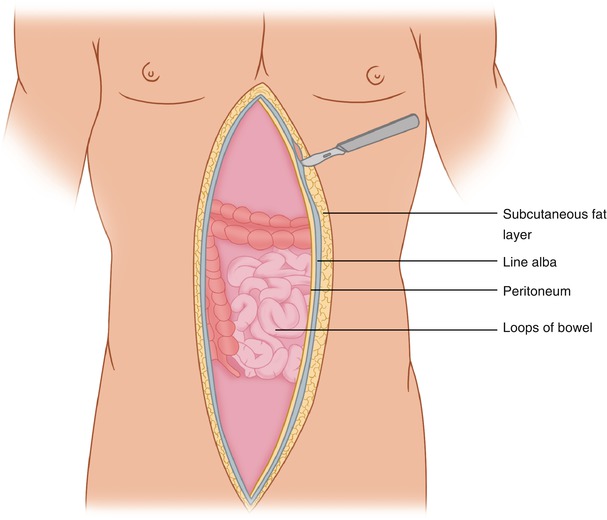

In cancer surgery, resection of the full thickness of the abdominal wall muscle layers is occasionally required because of their involvement by a tumor. The synthetic graft that may be placed to repair the abdominal wall defect will be in contact with bowel loops. Contact between loops of bowel and the undersurface of mesh may lead to the development of an enterocutaneous fistula, as shown in the reconstruction of full-thickness musculoaponeurotic abdominal wall defects.

In our experience between 1977 and 1986, 26 patients with abdominal wall defects due to extirpative surgery for a variety of malignant tumors had repair with a prosthetic material without any effort to interpose tissue between the bowel loops and the mesh. In this group, six patients (23 %) developed an enterocutaneous fistula at the area of contact. These enterocutaneous fistulae were more likely to occur in the lower half of the abdomen than in the upper part, because gravity makes it more likely that the bowel loops will descend and adhere tenaciously to the deep surface of the mesh. As a result of this experience, 30 patients with similar defects between 1986 and 1992 had interposition of tissue between the bowel loops and the mesh. When available, the greater omentum was used by suturing it to the undersurface of the mesh. Four patients had a free peritoneal patch sutured on the undersurface of the polypropylene mesh, which was facing the peritoneal cavity. In this group of 30 patients with tissue interposition, none developed a fistula [1].

Elongation of Omentum

For the omentum to reach the lower portions of the abdominal wall, elongation of this structure may be required. This is accomplished by separating the greater omentum off its attachment to the transverse colon and then freeing the gastroepiploic arcade from the greater curvature of the stomach. The branches between the gastroepiploic arcade and the wall of the stomach are ligated and divided. Finally, the left gastroepiploic artery, a branch of the splenic artery, is divided, allowing mobilization of the greater omentum, following lysis of any remaining attachments to the transverse colon, so that its lower end may reach the urinary bladder in the midline or the internal inguinal ring laterally. The blood supply of the omentum is maintained through the right gastroepiploic branch of the gastroduodenal artery. Occasionally, it may be more effective to divide the right gastroepiploic artery and have the entire greater omentum supplied by the left gastroepiploic vessels, depending on the location of the defect and the anatomical position of the bulk of the greater omentum.

Muscle Flap

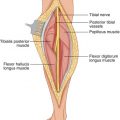

For full-thickness musculoaponeurotic defects in the lower quadrants of the abdominal wall and inguinal area, a muscle flap may be used. For example, a contralateral rectus abdominis flap may consist of the peritoneum posteriorly, the transversalis fascia, and the rectus abdominis based on the inferior epigastric vessels. A midline abdominal incision is made from the pubic symphysis to the xiphoid. The linea alba on the side opposite the defect is incised longitudinally, aiming to expose the medial edge and anterior surface of the rectus abdominis muscle (Fig. 21.1). The muscle is divided proximally at the level of the costal margin. The superior epigastric vessels running close to the posterior surface of the rectus abdominis are ligated and divided at the same level. The anterior sheath remains intact. At the lateral edge of the rectus, the posterior sheath is incised longitudinally about 1-cm medial to the linea semilunaris (Fig. 21.2). The combined sheet of transversalis fascia and peritoneum is divided transversely at the same level as the muscle and joins the vertically-placed incision along the linea semilunaris, which extends down to near the pubic crest, being careful to avoid injury to the inferior epigastric vessels as they ascend obliquely from the external iliac vessels to assume a position behind the rectus abdominis. In this type of rectus abdominis flap, the anterior rectus sheath remains intact in its normal anatomical position. The mobilized rectus flap can cover a defect in the contralateral lower quadrant, including the inguinal ligament (Fig. 21.3). That is, a left rectus abdominis flap may be mobilized to cover a defect of the right lower quadrant, and a right rectus abdominis flap can cover a defect in the left lower quadrant. In this case, when using a muscle flap, a skin graft must be placed on the exposed portion of the transposed muscle if the defect to be covered includes the skin. The muscle will reach the contralateral iliac crest. This flap is about 8-cm wide. For defects in the lower quadrants of the abdomen, particularly those involving loss of skin, a myocutaneous flap of the tensor fascia lata or a rectus femoris myocutaneous flap may be used; both are based on blood supply from the ipsilateral lateral femoral circumflex vessels of the profunda femoris. If the ipsilateral to the defect rectus is intact, the mobilized contralateral rectus may be passed in front or behind this muscle to reach the groin defect and be sutured to the edges of the defect.