Marlene L. Durand

Introduction to Eye Infections

Vision loss impacts daily life in so many ways that most people value their sight more than any other special sense. Eye infections that result in permanent vision loss can be devastating, and many eye infections rapidly threaten sight if not promptly diagnosed and treated. Infectious disease physicians appreciate how important their help may be to ophthalmologists but may find it difficult to interpret the ophthalmologist’s notes and specialized terminology. This brief review of eye anatomy and of the terminology commonly used by ophthalmologists may be helpful to the non-ophthalmologist caring for patients with eye infections.

Anatomy

Several points about eye anatomy are worth considering in particular.

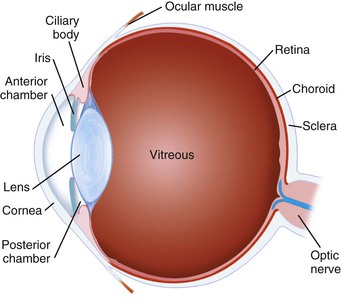

1. From an embryologic perspective, the eye may be thought of as having three “coats” (cornea/sclera, uvea, retina) and two humors (aqueous, vitreous) (Fig. 113-1). The cornea and sclera form a protective outer coat, with the cornea as a clear window. The uvea is highly vascularized and pigmented. It is composed of the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. The retina, embryologically, is an outpouching of the brain.

3. Aqueous humor is a liquid that is continuously produced and reabsorbed, with a turnover time of approximately 100 minutes. In contrast, the vitreous humor is a gel-like substance that forms in utero and is never regenerated. The rapid turnover of aqueous but persistence of vitreous is one reason why a break in the posterior lens capsule during cataract surgery greatly increases the risk of postcataract endophthalmitis. The aqueous is commonly contaminated by ocular surface flora during eye surgery, but these bacteria are usually cleared unless they reach the vitreous (see Chapter 116).

Types of Eye Infections

Patients with most types of eye infections have no systemic evidence of infection and usually feel well aside from their eye. The exceptions are patients with endogenous endophthalmitis, some types of uveitis, and orbital infections. However, even patients with these types of eye infections may be afebrile and have a normal white blood cell count.

Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis is characterized by eye irritation or discomfort but not significant pain unless there is also involvement of the cornea. The latter is then termed keratoconjunctivitis and may lead to corneal scarring (see Chapters 114 and 115).

Keratitis

Keratitis refers to infection of the cornea (see Chapter 115). The cornea is only 0.5 mm thick in the center and has a 5- to 7-cell-thick epithelium overlying the stroma and endothelium. Keratitis may occur in the epithelium only (e.g., dendritic keratitis in an initial episode of herpes simplex keratitis), the stroma or interstitium (e.g., interstitial keratitis of syphilis), or both as an infiltrate or ulceration (e.g., Pseudomonas keratitis). In cases of large corneal infiltrates or ulcerations, the keratitis may be appreciated even with a flashlight examination at the bedside.

Along with the overlying tear film, the cornea provides 65% to 75% of the refractive power of the eye, so keratitis usually causes decreased vision. The cornea has no blood vessels but many nerve endings, so keratitis is typically painful. Patients with decreased corneal sensation, such as from repeated attacks of herpetic keratitis, may not appreciate that they have a corneal infection until it is advanced, however.

Endophthalmitis

Endophthalmitis refers to bacterial or fungal infection inside the eye involving the vitreous or aqueous, or both (see Chapter 116). Infection may be introduced exogenously (i.e., from the outside in), such as from eye surgery or eye trauma, or endogenously, from bacteremia or fungemic seeding of the eye. Of note, endophthalmitis does not serve as a source for bacteremia or fungemia.

Uveitis

Uveitis refers to inflammation of the uvea (iris, ciliary body, choroid) or retina (see Chapter 117). Most cases are idiopathic or related to a rheumatologic condition, and the frequency of infectious etiologies varies by the type of uveitis. Uveitis is categorized by the location of maximal inflammation and thereby divided into four types: anterior (iritis, iridocyclitis); intermediate (pars planitis); posterior (retinitis, chorioretinitis, choroiditis); or panuveitis. It is important to understand the type of uveitis because the differential diagnosis, as well as the likelihood of an infectious etiology, varies by the anatomic category.

Periorbital Infections

Periorbital infections are those involving the soft tissues surrounding the globe of the eye (see Chapter 118). The term “periorbital” is not precise and encompasses both “preseptal” and “orbital.” It is important to distinguish preseptal from orbital infections. Preseptal infections involve the superficial part of the lids and do not threaten vision. Orbital infections (orbital cellulitis, subperiosteal abscess, orbital abscess) are much more serious and are often vision threatening. The two conditions may be distinguished on physical examination: orbital infections cause decreased vision, limitation in extraocular movement, and/or proptosis, whereas preseptal infections do not. Of note, the proptosis may not be obvious on gross examination and may only be detected by use of Hertel’s exophthalmometer. A difference between the eyes of 2 mm or more is significant.

Understanding the Ophthalmologist’s Note

The ophthalmologist’s examination starts with visual acuity and intraocular pressure measurements and then describes findings in sequence from the surface of the eye to the fundus. The ophthalmologist uses a slit lamp and indirect ophthalmoscope for a complete examination. The direct ophthalmoscope used by most non-ophthalmologists does not show most corneal abnormalities, the degree of intraocular inflammation, or provide a full view of the fundus. Perhaps as a consequence, many serious eye infections are initially misdiagnosed as conjunctivitis by the non-ophthalmologist. Symptoms that distinguish more serious eye infections from conjunctivitis include decrease in baseline vision and eye pain. Patients with these symptoms should be referred to an ophthalmologist for an urgent examination.

Visual Acuity and Measuring Low Vision

The ophthalmologist’s note usually starts with a measurement of visual acuity. This is measured both “with correction” and “without correction,” meaning correction of refractive error (e.g., through use of glasses). A “pinhole” visual acuity is measured by having the patient look through a card with a pinhole in it. This mimics optimal refraction and distinguishes visual loss due to uncorrected refractive error from more serious etiologies.

Patients with low vision are particularly affected by lighting conditions, and the non-ophthalmologist should keep this in mind. Patients being examined at the bedside in a dimly lit hospital room may have better vision when examined under good lighting.

The best visual acuity the patient can achieve with each eye is always recorded. Patients with serious eye infections may have worse vision than can be measured by use of the Snellen eye chart: the “big E” at the top of the chart is 20/400 vision. If the patient has very low vision, it is recorded as one of the following, in descending order: “count fingers” (CF), “hand motion” (HM), or “light perception” (LP). For count fingers vision, the distance of the examiner’s fingers is recorded, so “CF at 3 feet” is recorded and represents better vision than “CF at 1 foot.” If the patient cannot detect a bright light shining directly in his or her eye, he or she has “no light perception” (NLP) vision, or complete blindness in that eye. Visual recovery from NLP is extremely unlikely in an infected eye unless the NLP recording is transient. Any vision better than NLP is worth saving, and an aggressive approach to eye infections is important: patients value even LP vision. In addition, there are many factors that affect vision in the setting of an acute eye infection, and some of these are reversible. The patient’s vision 3 months after an acute bacterial endophthalmitis, for example, is usually much better than it is 3 days after presentation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree