Francisco Averhoff, Yury Khudyakov, Beth P. Bell *

Hepatitis A Virus

Hepatitis A is generally an acute, self-limited infection of the liver by an enterically transmitted picornavirus, hepatitis A virus (HAV). Infection may be asymptomatic or result in acute hepatitis. Rarely, fulminant hepatitis can ensue. Although the duration and severity of symptoms vary widely, HAV infections never cause chronic liver disease. The availability of effective vaccines against hepatitis A has markedly affected the epidemiology of hepatitis A in places where the vaccines are widely used, as in the United States (see later).

History

The earliest accounts of contagious jaundice are from ancient China.1 Although the symptoms that were described are similar to those currently found in people with hepatitis A, it should be remembered that a number of other infections produce similar symptoms. The earliest outbreaks of hepatitis that were almost certainly hepatitis A were documented in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, especially during periods of war. From 1855, the disease became known as “catarrhal jaundice” because the pathologists Bamberger and Virchow believed that the disease was caused by blockage of the common bile duct by a plug of inspissated mucus.2 The first suggestion that the disease was caused by an infectious agent was made by McDonald,3 who, unable to demonstrate the involvement of enteric bacteria, suggested that the infection might be caused by a virus. Shortly thereafter, Cockayne4 proposed that the sporadic and epidemic forms of jaundice were manifestations of the same disease. In 1923, Blumer analyzed a large number of epidemics of hepatitis in the United States and identified its predilection for young adults and children and peak incidence in winter and fall.5 Hepatitis A had an incubation period of between 15 and 49 days and was transmitted by the fecal-oral route.6–8 Later studies demonstrated that the virus could be detected in feces or blood during the acute infection, that infection could be transmitted experimentally by both the oral and parenteral routes, and that infection was followed by long-term immunity and could be prevented by previous administration of normal human immune globulin (IG).5,9 In addition, the disease was shown to be associated with a filterable agent resistant to heating at 56° C for 30 minutes and resistant to diethyl ether. In the 1950s and 1960s, Krugman10 expanded these observations by a series of studies in human volunteers that further defined the incubation period, period of infectivity, and period of viremia, and they developed standardized reagents representing hepatitis A. In 1973, Feinstone and colleagues11 detected 27-nm virus-like particles in the stools of volunteers infected with hepatitis A and demonstrated that they were aggregated by convalescent but not by preinfection serum, thus indicating that the particles represented the etiologic agent of the disease. The identification of HAV, transmission of the disease to marmosets and chimpanzees, propagation of HAV in cell culture, and molecular cloning of the viral genome ushered in a new era of research that culminated almost 2 decades later in the development and licensing of effective vaccines.12–18

Classification and Physicochemical and Biologic Properties of Hepatitis a Virus

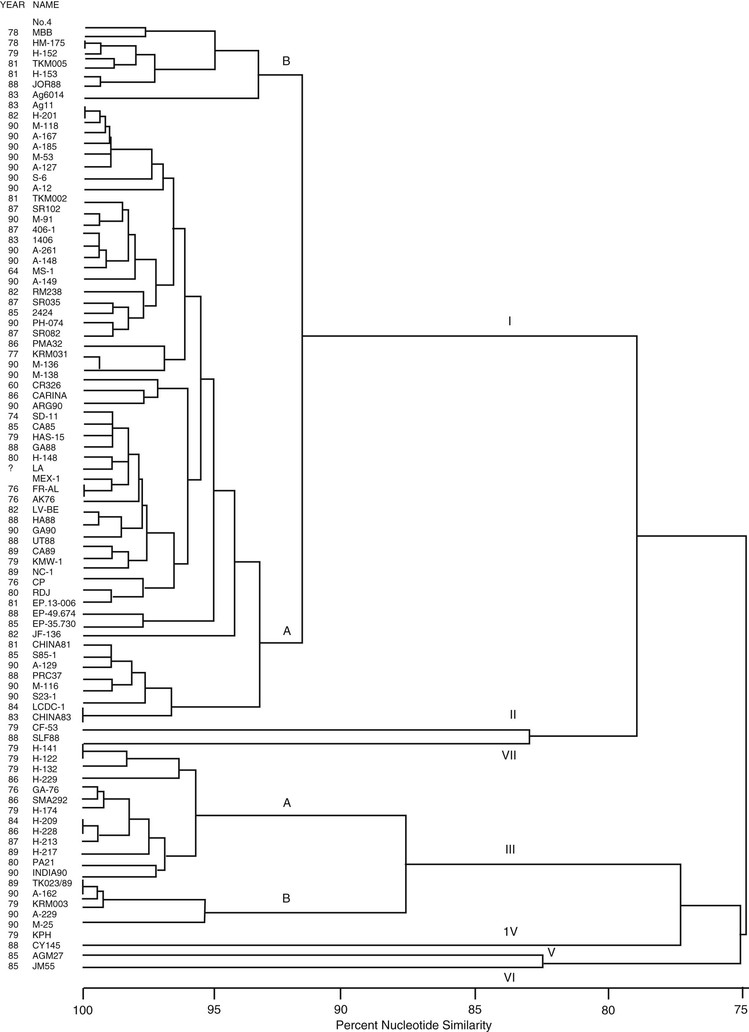

HAV is a nonenveloped, positive-strand RNA virus member of the Picornaviridae family, which includes the enteroviruses, parechoviruses, and rhinoviruses of humans, as well as the aphthoviruses (foot-and-mouth disease viruses) of hoofed animals and cardioviruses (encephalomyocarditis virus) of mice. Although HAV shares general structure and genomic organization with the other picornaviruses, it has limited nucleotide sequence homology and certain distinguishing characteristics that have resulted in its being classified in its own genus, Hepatovirus.19–21 Recently, avian encephalomyelitis virus has been tentatively reclassified as a second member of the Hepatovirus genus.22 Human isolates of HAV are relatively closely related on the basis of partial genomic sequences. However, human HAV strains have been divided into three genotypes, I, II, and III, on the basis of phylogenetic analysis of sequences of the complete VP1 region.23 The other three genotypes, genotypes IV, V, and VI, are all single simian HAV isolates.24 Phenotypic differences such as disease severity among the genotypes have not been well recognized. Recently, however, some association of fulminant hepatitis with infections with certain genotype IB strains in the United States was suggested.25 In Korea, patients infected with genotype IIIA were reported to have significantly higher aminotransferase levels, prothrombin time and leukocyte count, and more severe symptoms than patients infected with IA.26 Additionally, mutations in the 2B coding region were shown to be associated with severe and fulminant disease.27,28 Although antigenic variants exist among all genotypes, there is only one recognized serotype of HAV on the basis of cross-neutralization studies.

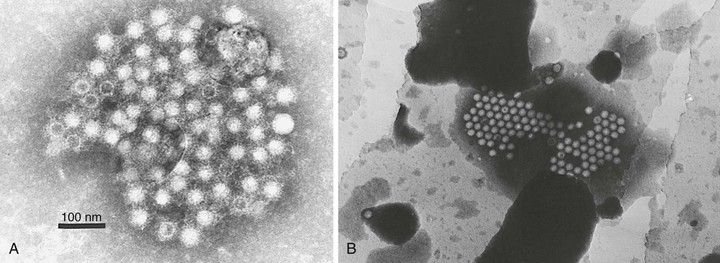

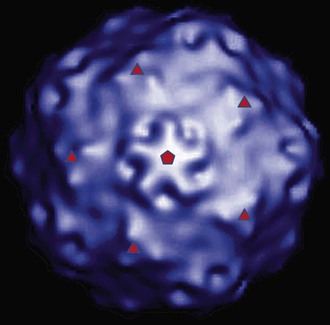

Structure

HAV is a 27- to 28-nm spherical, nonenveloped virus11 (Fig. 176-1) with a surface structure suggesting icosahedral symmetry.29 High-resolution x-ray crystallography of HAV has not yet been achieved. However, good-quality cryoelectron microscopy has confirmed the icosahedral symmetry of the virion with typical picornavirus threefold and fivefold axes and 60 repeated pentamers comprising the capsid (Fig. 176-2; see Fig. 176-1). The cryoelectron microscopic views of HAV reveal the plateau surrounding the fivefold axis that is typical for picornaviruses, but not the pit or canyon believed to be the receptor-binding site of enteroviruses and rhinoviruses (see Fig. 176-2). The prominence at the threefold axis of symmetry is distinct from other picornaviruses and is believed to be the major antigenic site at which neutralizing antibodies are targeted.

Purification of virus from clinical samples or tissue culture yields three distinct populations of particles30: (1) mature hepatitis A virions that band at 1.32 to 1.34 g/cm3 in cesium chloride and sediment at approximately 160 S (similar to enteroviruses and cardioviruses), (2) a lower-density fraction that bands at approximately 1.27 g/cm3 in cesium chloride, and (3) sediments at 70 to 80 S that may represent empty capsids or particles with incomplete genomes and a high-density fraction (1.4 g/cm3) that may represent particles with a more open virion structure that allows increased penetration and binding of cesium chloride to the viral particle. These high-density particles have been shown to contain RNA but tend to be less stable than mature virions.31,32

HAV released from cells was shown to be enveloped in host-derived membranes that protect the virion from antibody-mediated neutralization. These enveloped viruses are fully infectious and circulate in the blood of infected humans. Antibodies to capsid restrict HAV replication after infection with the enveloped virus, suggesting a possible mechanism for postexposure prophylaxis.33

Resistance to Physical and Chemical Agents

HAV is a relatively stable virus under a variety of environmental conditions. HAV is more resistant to heat than other picornaviruses and may not be completely inactivated (depending on the conditions) by exposure to 60° C for 10 to 12 hours.34–36 Complete inactivation in food requires heating to higher than 85° C for at least 1 minute.36 Outbreaks of hepatitis A have been reported after ingestion of steamed shellfish, suggesting that the internal temperature achieved by steaming sometimes may be insufficient to destroy the virus.37 However, HAV can be reliably inactivated by autoclaving (121° C for 30 minutes).38 Recent studies have shown that HAV can be inactivated in shellfish by a nonthermal method using high hydrostatic pressure.39 The virus is resistant to most organic solvents and detergents and to a pH as low as 3.38,40 HAV can be inactivated by many common disinfecting chemicals including hypochlorite (bleach) and quaternary ammonium formulations containing 23% HCl (found in many toilet bowl cleaners).38 Currently licensed vaccines are inactivated by 1 : 4000 formalin at room temperature for at least 15 days to exceed complete inactivation by at least threefold. As a result of several outbreaks of hepatitis A in hemophiliacs who received factor VIII concentrates that had been treated by a solvent detergent method for inactivation of lipid-enveloped viruses, interest has focused on techniques capable of inactivating nonenveloped viruses without compromising the biologic activity of the product.41 Various manufacturers use different techniques to inactivate or remove HAV and human parvovirus B19. These include nanofiltration and other purification techniques, sensitive nucleic acid testing such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on minipools of source plasma, pasteurization at 60° C for 10 hours, and dry heat on lyophilized products.

Genome and Proteins

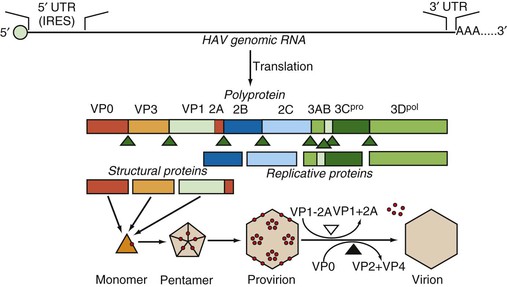

Although HAV had the characteristics of a picornavirus and indirect tests suggested an RNA genome, molecular cloning and sequence analysis demonstrated that the HAV genome is composed of single-stranded, positive-sense linear RNA of 7478 nucleotides (strain HM175) and a molecular weight of approximately 2.25 × 106 Da, with an overall structure and gene order typical of picornaviruses.17,19,42

The 5′ end of the genome does not have a cap structure but instead, as is typical for picornaviruses, has a small, covalently bound protein termed VPg.39 The genome itself has a long 5′ untranslated region beginning with UU as found in all picornaviruses. This 5′ untranslated region folds to form a highly ordered secondary structure that is important for both replication and translation. These structured regions include an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) that directs the initiation of translation at either of two AUG codons at nucleotide positions 735-737 and 741-743 (see Fig. 176-3).42 The AUG codon initiates a single long open reading frame of 6681 nucleotides that encodes a polyprotein that is 2227 amino-acid residues in length. The coding region of picornaviruses has been arbitrarily divided into three parts, termed P1, P2, and P3, and the peptides that are ultimately cleaved from the translation products of these regions are referred to as 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, and so forth, in order of translation from the 5′ to the 3′ end of the genome.43 The HAV genome ends with a 3′ noncoding region of 63 nucleotides that is followed by a virus-encoded poly (A) tail.

A peculiar property of the HAV coding region is a highly deoptimized codon usage. The HAV genome is significantly biased against codons used abundantly by human cells. The accumulation of rare codons was hypothesized to result in the reduced translation rate and modulation of translation kinetics of HAV RNA, thus playing an important role in HAV replication and evolution.44,45

The four capsid proteins of mature virus particles are coded by the first 2373 nucleotides (P1) and the nonstructural proteins by the remainder (P2 and P3). The four capsid polypeptides named by analogy with other picornaviruses are referred to in descending order of size as virion proteins (VP): VP1 = peptide 1D (molecular weight 32,800 Da), VP2 = 1B (24,800 Da), VP3 = 1C (27,300 Da), and VP4 = 1A (2500 Da).22,46 A VP0 protein (1AB) that is the precursor to VP4 and VP2 can also be detected, especially from cell cultures where immature virions (provirions) may accumulate in large amounts.47 The VP4 molecule is believed to be liberated during the maturation cleavage of VP0, which converts provirions to virions (see later), but VP4 has never been experimentally determined to be within the virion particle and, at just 23 amino acids, is approximately one third the size of the VP4 proteins of other picornaviruses.

Assembly of HAV particles proceeds through several steps (Fig. 176-3). Cleavage of the polyprotein by the 3C protease yields three capsid-related proteins, VP0, VP3, and VP1-2A (also known as PX), which constitute a monomer and subsequently assemble into pentameric subunits. Twelve copies of the pentamer then associate with viral RNA to form provirions or without viral RNA to form empty capsids (procapsids). The involvement of the VP1-2A precursor in assembly is unique to HAV, and it has been shown that the 2A extension is essential for proper processing and assembly of the pentameric subunit.48–50 After assembly, 2A is removed from VP1 by cellular proteases,51,52 and in the final maturation step, VP0 is cleaved to yield VP2 and VP4. The VP0 cleavage is dependent on the presence of viral RNA in the particle, and procapsids therefore fail to cleave VP0, but HAV procapsids are quite stable and seem to have the same antigenic structure as mature virions.

Antigenic Composition and Viral Diversity

Although a variety of genotypes of HAV have been identified by analysis of genome sequences (Fig. 176-4), there seems to be only one serotype.53–55 This view is supported by the observation that IG prepared in developed countries and monovalent vaccines prepared from strains originating in Australia, Central America, or Europe protect travelers from disease equally well, irrespective of their destination.56,57

Neutralization sites for HAV are located primarily on the structural proteins VP1 and VP3, with possibly a minor contribution from VP2.53 Monoclonal antibodies in competition binding assays and the generation of neutralization escape mutants suggest that the dominant neutralization site is composed of overlapping epitopes on VP1 and VP3 that combine to form a conformational antigenic site at which neutralizing antibodies are targeted.53,55,58

Classification of HAV into genotypes and subtypes was originally suggested using a 168-nucleotide fragment containing the VP1/P2A junction. Genotypes differ by at least 15% and subtype by 7% to 7.5% from each other in this region.24 Seven genotypes, I to VII, identified using this approach were recently reclassified into six genotypes, I to VI, using the complete VP1 region. Genotypes I, II, and III are divided into subtypes A and B. The former genotype VII is classified as subtype IIB (2). These three genotypes infect humans, whereas genotypes IV to VI have a simian origin.24,59,60 Genotypes have a particular geographic distribution.24,61,62 Genotype I is most prevalent worldwide, with subtype IA being more common than IB, and is the most common in the United States.24,61 Although IB usually constitutes only a small fraction of genotype I strains circulating in South and North America, Europe, Asia, and Africa,60 it was reported among 35% to 70% of patients infected with HAV genotype I in Brazil.63,64 Genotype 1B is predominant in the Middle East65,66 and South Africa.67 Genotype II isolates originally identified in France in 1979 and Sierra Leone in 198824 are not frequently reported. Subtype IIA was suggested to have West African origin.68 Genotype III can be identified globally,60 but it is endemic in Southeast and Central Asia.24 An increase in genotype IIIA infections was recently reported in Korea and Russia.26,69 In India, reported hepatitis A outbreaks have all been caused by genotype IIIA infections.70–72 Genomic heterogeneity of HAV is used to track transmissions during outbreak investigations,62 with the VP1/P2A region being most frequently applied for genetic identification of HAV strains.62,73 Although individual strains of HAV have differences at the molecular level that may be useful for epidemiologic studies, a high degree of identity in nucleic acid (up to 90%) and amino acid sequence (up to 98%) is generally seen between strains.62,74

Biology of Hepatitis A Virus in Cell Culture

HAV was first propagated in marmoset liver explant cultures and a cloned line of fetal rhesus monkey kidney cells (FRhK-6) with a strain of virus (CR326) that had been adapted by multiple passages in Saguinus mystax and Saguinus labiatus marmosets.14 Many HAV strains have subsequently been isolated from clinical material, although the procedure may take several weeks. Until recently, only epithelial or fibroblast cells of primate origin had been shown to support growth of the virus.15,16,75 However, in a systematic search for cells that would support HAV replication, growth was detected in cells of guinea pig, dolphin, and porcine origin.76

The major characteristics of HAV in cell culture are slow growth and low yields relative to other picornaviruses. In addition, the virus remains largely cell associated, does not usually produce a cytopathic effect, and readily leads to persistently infected cell lines.77 With adaptation, more rapid replication and higher yields can be obtained and cytopathic variants have been selected. These cell culture–adapted viruses are useful for virus titrations, neutralization, inactivation kinetics, and virus replication and have made the production of inactivated vaccines practical.14,16,78–80

In one study, direct isolation of a wild-type strain of HAV was achieved through the use of a modified cell line.81 Detection of HAV in either patients’ or environmental samples is now done primarily through the use of PCR or other nucleic acid-based technology. The kinetics of viral replication and biosynthetic events has been studied in cells infected with cell culture–adapted strains of HAV and reveal a number of differences from most other picornaviruses. After attachment to cells, the uncoating of virus is delayed for more than 8 hours82,83; this exceeds the duration of an entire growth cycle for many picornaviruses. The delayed uncoating seems to be related to the protracted maturation cleavage of VP0 to VP2 and VP4 because virions are uncoated more rapidly than provirions.84 Accumulation of new viral RNA can be detected as early as 12 hours after infection of BS-C-1 cells with a fast-growing, cytopathic variant of strain HM175, but levels of viral replicative intermediates (double-stranded RNAs) remain much lower than in cells infected with other picornaviruses.82 As outlined previously, translation of the viral polyprotein is directed by the IRES within the 5′ untranslated region, but the IRES of HAV is relatively inefficient, with initiation approximately 1% of that seen for the IRES of encephalomyocarditis virus.85–87

The initial proteolytic processing of HAV polyprotein is accomplished by the viral 3C protease, and assembly of viral particles proceeds via monomers and pentamers (see Fig. 176-3).48 After infection of cell cultures with rapidly replicating and cytopathic variants of HAV, pentamers are first detected at 9 hours after infection and reach peak levels after approximately 18 hours even though the amount of viral RNA (and presumably viral translation) increases beyond this time.88 These cells continue to produce virus for 2 to 3 days before cell death, whereas most HAV variants progress to a persistent infection with reduced levels of virus production over many weeks and subsequent cell passages.

Repeated passage in cell culture has been used to apply mutational pressure to HAV to alter the phenotype. For example, HAV variants that grow more rapidly or are resistant to neutralization by monoclonal antibodies have been selected.80,89,90 Attenuated strains of HAV have been selected by multiple tissue culture passages, and cold adaptation has been achieved by passage at reduced temperature.29,91 Some of the mutations responsible for these altered phenotypes have been identified by molecular cloning and sequencing of the mutant. Mutations within the 5′ untranslated region and mutations within the 2B and 2C coding regions of HAV RNA have been shown to enhance virus replication in vitro.90,92,93 However, mutations within the VP1-2A and 2C proteins seem to be most important for attenuation of virulence.90

Most viruses initiate infection by first binding to a specific cell surface receptor molecule or, in many cases, may require binding to both receptors and co-receptors to facilitate virus entry and uncoating. Identification of a specific receptor for HAV remained elusive for many years. However, Kaplan and colleagues94 succeeded in the isolation of one specific receptor molecule, havcr-1, first in cells of simian origin and later in human cells.95 This molecule is a novel mucin-like class I integral membrane glycoprotein of 451 amino acids, with the amino-terminal, cysteine-rich domain responsible for binding to HAV.95 Because this molecule is expressed on cells from many tissues that are not susceptible to HAV infection, it is likely that specific co-receptors contribute to the organ tropism of HAV. However, a soluble form of havcr-1 has some ability to neutralize particles of HAV directly, which is consistent with roles in both attachment and uncoating of virus.96

It remains possible that HAV may use other pathways for cell entry in addition to havcr-1. Recent studies demonstrated that the asialoglycoprotein receptor can also mediate infection of cells with HAV when the virus is first complexed with specific IgA, leading to the interesting hypothesis that IgA may play a role as both carrier and targeting molecule during infection and transmission, particularly in relapsing cases of HAV.97

Host Range

Humans are considered to be the only important reservoir of HAV. However, the existence of extra human reservoirs of infection remains possible. In 1961, Hillis98 described an outbreak of hepatitis A among chimpanzee handlers who apparently contracted the infection from the chimpanzees. Epidemiologic data suggested that the animals had become infected during captivity but before their importation into the United States. Interestingly, although epidemics of hepatitis were recognized in American primate handlers, the disease was rarely seen in Africa, presumably because most handlers were already immune. Widespread screening of nonhuman primates revealed antibodies to HAV in chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, gibbons, macaques, owl monkeys, pig tail monkeys, rhesus monkeys, and several species of South American tamarin monkeys.99,100 It is unclear whether such primates may serve as reservoirs of infection or as transient hosts after exposure to HAV from human sources. However, both the PA21 and AGM-27 strains of HAV seem to be true simian viruses.101,102 Interestingly, the AGM-27 virus produces attenuated disease in chimpanzees and was the subject of some study as a potential live attenuated vaccine.103

Deinhardt104 pioneered the use of nonhuman primates for hepatitis A studies in both chimpanzees and tamarins (Saguinus species). He showed that in chimpanzees, liver function test abnormalities developed on inoculation with known infectious material of human origin. Since that time, the chimpanzee, several species of tamarins, and the owl monkey have all been shown to be susceptible to HAV infection and to develop hepatitis.104 These animals have been valuable tools in the study of hepatitis A pathogenesis and for the development of vaccines. Recently, it was shown that guinea pigs express a receptor similar to the human HAV receptor and that both guinea pig cells and guinea pigs can be infected with HAV. However, the animals did not have evidence of hepatitis.76,105

Epidemiology

Modes of Transmission

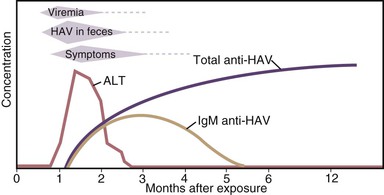

HAV is primarily transmitted by the fecal-oral route. After replication in the liver, the virus is excreted in bile and is found in highest concentrations in stool. In experimental studies, infectivity of stools was demonstrated for 14 to 21 days before to 8 days after onset of jaundice, but the highest concentrations occur during the 2-week period before jaundice develops or liver enzymes increase, followed by a rapid decrease after the appearance of jaundice (Fig. 176-5).11,106,107 Data from epidemiologic studies also suggest that peak infectivity occurs during the 2 weeks before the onset of symptoms.108 Shedding of HAV in stool may continue for longer periods in infected infants and children than in adults. HAV RNA has been detected in stool of infected newborns for as long as 6 months after infection.109 Excretion in older children and adults was demonstrated 1 to 3 months after clinical illness.57,109 Although chronic shedding of HAV does not occur, the virus has been detected in stool during relapsing illness.110

During the period of viremia, which begins during the prodrome and extends through the period of increased liver enzymes (see Fig. 176-5), HAV concentrations in serum are several orders of magnitude lower than in stool.111–113 However, in experiments conducted in nonhuman primates, HAV was several orders of magnitude more infectious when administered by the intravenous compared with the oral route, and animals were successfully infected with low concentrations of HAV administered via the intravenous route.114 Although HAV may occasionally be detected in saliva in experimentally infected animals and may be present in human saliva,115,116 transmission by saliva has not been demonstrated.

Enzyme immunoassays and PCR may detect defective and infectious viral particles. Thus, the detection of HAV antigen in the stool by enzyme immunoassays or HAV RNA in the serum, stool, or saliva by PCR does not mean that an infected person is necessarily infectious, and it is likely that the period of infectivity is shorter than the period during which HAV RNA is detectable. For practical purposes, both children and adults with hepatitis A can be assumed to be noninfectious 1 week after jaundice appears.

Person to Person

Person-to-person transmission by the fecal-oral route remains the primary means of HAV transmission throughout most of the world.117,118 Transmission can occur among close contacts, particularly in households and extended family settings.119 In the United States prior to the introduction of hepatitis A vaccine, young children had the highest rates of infection. Further, these children often serve as a source of HAV infection for others because HAV infection is often asymptomatic and standards of hygiene are generally lower in young children compared with adults, as in daycare facilities.119–121

Foodborne and Waterborne

HAV can remain infectious in the environment for long periods of time,122 allowing for common source outbreaks and sporadic cases to occur from exposure to fecally contaminated food or water. Many uncooked foods have been recognized as the source of outbreaks. Cooked foods also can transmit HAV if the cooking is inadequate to kill the virus or if the food is contaminated after cooking, as commonly occurs in outbreaks associated with infected food handlers.123–125,126 Contaminated shellfish were responsible for a large outbreak in Shanghai, China, in 1988.127,128 Although outbreaks continue to be reported,129–130,131 shellfish-associated HAV outbreaks in the United States and other developed countries have become increasingly uncommon. In Italy, detection of HAV in samples of shellfish has decreased, believed to be the result of hepatitis A vaccination programs in that country.132 Waterborne outbreaks of hepatitis A are also now uncommon in developed countries. Molecular techniques allow for identification of common source foodborne hepatitis A outbreaks around the globe.133,134

Bloodborne

Transfusion-related hepatitis A is rare because HAV does not result in chronic infection, and, in the developed world, blood donors have been screened for many years for elevated aminotransferase levels. However, transmission by transfusion of blood or blood derivatives collected from donors during the viremic phase of their infection has been reported, including outbreaks in Europe and the United States among patients who received factor VIII and IX concentrates prepared using solvent-detergent treatment to inactivate lipid-containing viruses.41,113,135,136–138 HAV is resistant to solvent-detergent treatment, and contamination presumably occurred from plasma donors with hepatitis A who donated during the incubation period. The degree to which transfusion-related transmission occurs in developing countries where screening for blood and blood products may be limited is unknown.

Vertical

Two published case reports describe intrauterine transmission of HAV during the first trimester, resulting in fetal meconium peritonitis.139,140 After delivery, both infants were found to have a perforated ileum. The risk of transmission from pregnant women who develop hepatitis A in the third trimester of pregnancy to newborns appears to be low.141 However, newborns who acquire infection in this manner are usually asymptomatic, and an outbreak among hospital staff related to exposure to such an infant has been reported.142

Worldwide Disease Patterns

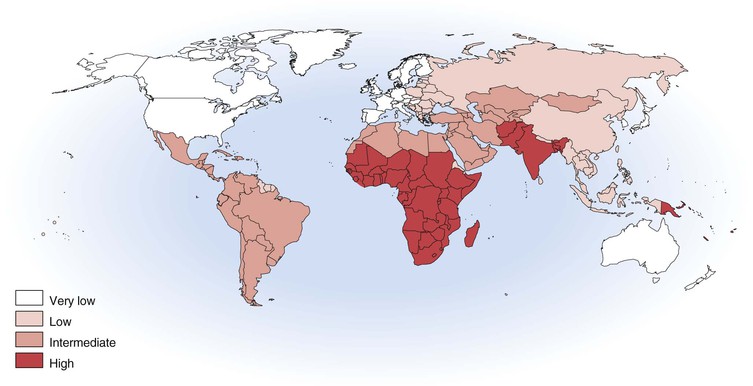

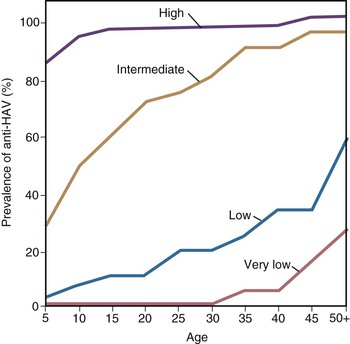

With more than 100,000 deaths globally caused by hepatitis A, it is one of the leading causes of death among vaccine-preventable diseases.143 Although hepatitis A occurs worldwide, major geographic differences exist in endemicity and resulting epidemiologic features (Fig. 176-6).144 The degree of endemicity is closely related to hygienic and sanitary conditions and other indicators of the level of development. In less developed areas, especially when there is limited access to clean water and inadequate disposal of human feces, HAV infects most people early in life, when infection is rarely clinically apparent (Fig. 176-7). When high standards of hygiene and sanitation apply, the majority of adults remain susceptible. Distinct patterns of HAV infection can be described, each characterized by particular age-specific anti-HAV prevalence and hepatitis A incidence and prevailing environmental (hygienic and sanitary) and socioeconomic conditions (see Fig. 176-7).117,144

In areas of high endemicity, represented by the least developed countries (i.e., parts of Africa and Asia), poor hygienic and sanitary conditions allow HAV to spread readily (see Figs. 176-6 and 176-7). Infection is nearly universal in early childhood, when asymptomatic infection predominates, and essentially the entire population is infected before reaching adolescence, as demonstrated by the age-specific prevalence of anti-HAV (see Fig. 176-7).145,146 Because most adults are immune, reported disease rates in this population are low and few outbreaks occur. However, susceptible adults in these areas are at high risk for hepatitis A. Recent surveillance data have demonstrated increasing numbers of cases among adults, and small seroprevalence studies have identified greater susceptibility of some children into adolescence, in some highly endemic countries.147–149 Differences in susceptibility to hepatitis A in low and middle income countries can be defined by socioeconomic status, where more affluent children living in more hygienic conditions are more likely to escape HAV infection as infants and young children, leaving them susceptible to HAV infection as adolescents and adults.150 In past years, some ethnic or geographically defined groups within highly developed countries also experienced high endemicity, including Native American, aboriginal populations in Australia, and Roma populations in Slovakia.151–153

In areas of moderate endemicity, HAV is not transmitted as readily because of better sanitary and living conditions, and the predominant age at infection is older than in areas of high endemicity (see Figs. 176-6 and 176-7).144,154 Paradoxically, the overall incidence and average age of reported cases are often higher than in highly endemic areas because high levels of virus circulate in a population that includes many susceptible older children, adolescents, and young adults who are more likely to develop symptoms with HAV infection.155 Large common source food- and water-associated outbreaks can occur because of the relatively high rate of virus transmission and large number of susceptible persons, especially among those of higher socioeconomic level. Such an outbreak occurred in Shanghai in 1988, with more than 300,000 cases associated with consumption of clams harvested from water contaminated with human sewage.127 Nevertheless, person-to-person transmission in community-wide epidemics continues to account for much of the disease in these countries.

Shifts in age-specific prevalence patterns that reflect a transition from high to intermediate endemicity are occurring in many parts of the world (see Fig. 176-6). A feature of this transitional pattern is striking variations in hepatitis A epidemiology among countries and within countries and cities, with some areas displaying a pattern typical of high endemicity and others of intermediate endemicity.117,156–162,163–167 Considerable hepatitis A–related morbidity and associated costs occur with this transition, even in developing countries.168,169 For example, hepatitis A was the etiology of the fulminant hepatitis of two thirds of children presenting to two hospitals in Argentina during a 15-year period, and, in one of these hospitals performing liver transplantations, one third of liver transplantations among children were performed for fulminant hepatitis A.168

In high-income, developed countries, including the United States, Canada, and much of western Europe, the endemicity of HAV infection is low or very low (see Fig. 176-6). Few children are infected, the incidence of disease is generally low, and disease is usually sporadic. Community-wide and child care center outbreaks may occur, although such outbreaks are becoming increasingly rare because of routine hepatitis A vaccination of children.117,138,152,170–174 Population-based seroprevalence surveys show a gradual increase in the prevalence of anti-HAV with increasing age, primarily reflecting declining incidence, changing endemicity, and resultant lower childhood infection rates over time. In countries where hepatitis A vaccine has been introduced, such as the United States, anti-HAV prevalence is increasing among children as a result of vaccination.175 In low and very low endemicity countries, most cases occur in defined risk groups such as travelers returning from endemic areas, men who have sex with men, and users of injection drugs.138,174,176–181 The risk of hepatitis A among children and other contacts of family members who are residing in low endemic countries and travel to their high or intermediate endemic country of origin is documented.182,183,184

Epidemiology in the United States

Hepatitis A epidemiology in the United States can be divided into two time periods, before and after implementation of national recommendations for use of hepatitis A vaccine.

Prevaccine Era

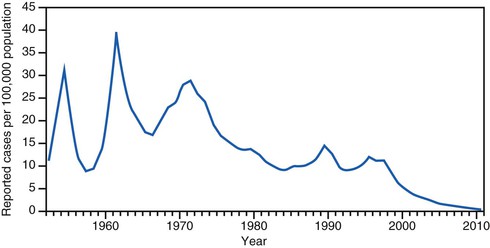

In the prevaccine era, hepatitis A incidence was primarily cyclic, with peaks every 10 to 15 years (Fig. 176-8). Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s in the United States, approximately 25,000 to 35,000 hepatitis A cases were reported annually to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,185 but incidence models indicated that the actual number of infections occurring during that period was likely 10 times greater with an estimated 271,000 infections per year.121

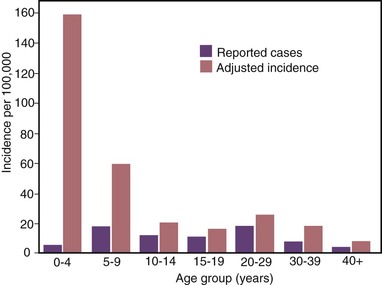

The highest hepatitis A rates were among children 5 to 14 years of age, with approximately one third of cases occurring among children younger than 15 years.186 Furthermore, because young children are more likely to have unrecognized or asymptomatic infection than older individuals, incidence models estimated that more than half of HAV infections occurred among children younger than 10 years old, the majority of which were in children younger than 5 years old (Figs. 176-9 and 176-10).121

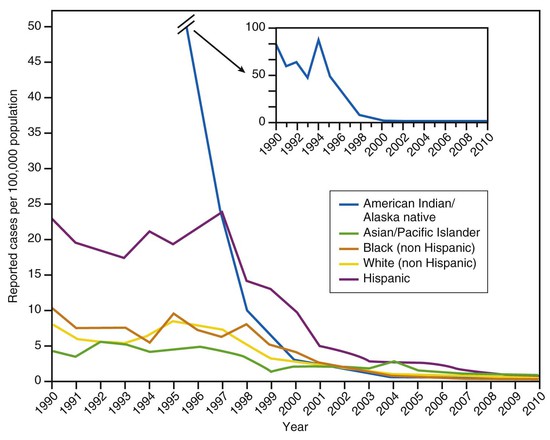

In the prevaccine era, hepatitis A incidence differed among racial and ethnic groups, with rates among Native Americans and Alaska Natives that were more than five times those in other racial/ethnic groups, and rates among Hispanics that were approximately three times higher than those among non-Hispanics (Fig. 176-11).187

Hepatitis A incidence also exhibited striking regional variation with the highest rates and majority of cases consistently occurring in a limited number of states and counties in the western and southwestern United States. During 1987-1997, cases among residents of 11 primarily western states, representing 22% of the U.S. population, on average accounted for 50% of reported cases.188 An additional 18% of cases occurred among residents of six additional states.

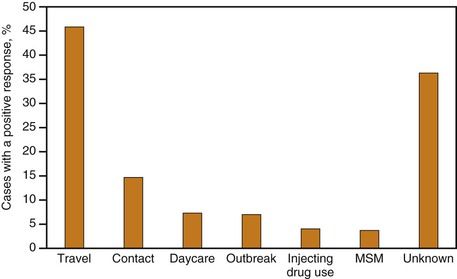

In the prevaccine era, most cases of hepatitis A in the United States occurred in the context of community-wide epidemics in which infection was transmitted from person to person in households and extended family settings.118,189 In these outbreaks, no single risk group accounted for the majority of cases, and infections among children, many of whom were asymptomatic, played an important role in sustaining transmission. For cases in which a risk factor could be determined, the most frequently reported source of infection was household or sexual contact with another person with hepatitis A, accounting for 12% to 25% of cases. Cyclic outbreaks also occurred in injection and noninjection drug users and among men who have sex with men; up to 15% of nationally reported cases occurred among persons reporting one or more of these behaviors. Other potential sources of infection such as international travel and foodborne outbreaks accounted for a small proportion of cases. For approximately 50% of reported cases, no source of infection could be identified.

Results of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, conducted from 1988 to 1994, indicated that approximately one third of the U.S. population had serologic evidence of previous HAV infection.190 Anti-HAV prevalence was related directly to age, ranging from 9% among children 6 to 11 years of age to 75% among persons older than 70 years of age and was related inversely to income. Anti-HAV prevalence was highest among Mexican Americans (70%) compared with non-Hispanic blacks (39%) and whites (23%).

Vaccine Era

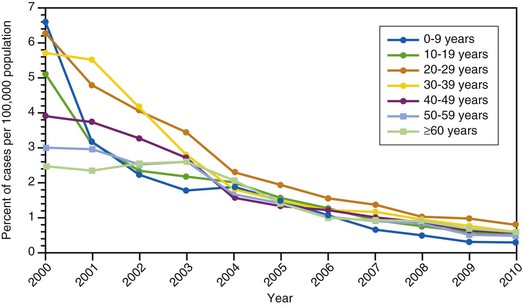

With the availability in the United States of hepatitis A vaccines beginning in 1995, hepatitis A became one of the most frequently reported vaccine-preventable diseases.185 Recommendations for use of hepatitis A vaccine were made by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) in 1996187 and expanded in 1999.188 The most recent update was in 2006, when the ACIP recommended that all children be vaccinated against hepatitis A at 1 year of age191 (see “Disease Control Strategies”). Recent seroprevalence data from the United States have shown an increase in anti-HAV seroprevalence in children, reflecting vaccination programs targeting children.175 National hepatitis A rates have been decreasing precipitously. In 2010, rates reached a historical low at 0.5 cases per 100,000 population (see Fig. 176-8) and only 1670 cases were reported that year, representing an almost 95% decrease from the more than 31,000 cases reported in 1995, before vaccine was introduced.192 This remarkable decline in incidence is reflected in other fundamental shifts in hepatitis A epidemiology, as described later.

Variation by Age, Race or Ethnicity, and Region

Hepatitis A incidence rates among children have decreased more sharply than among adults after the implementation of routine vaccination of children, and since 2002, rates have been similar among adults and children (see Fig. 176-10).192

Previous disparities in rates across racial/ethnic groups have largely disappeared (see Fig. 176-11).192 By 2000, hepatitis A incidence among Native Americans and Alaska Natives had decreased by 97% compared with the beginning of the decade and by 2010 was the lowest ever recorded (0.2/100,000).192 The disparity in incidence between Hispanics and non-Hispanics has also nearly disappeared.192 The geographic variations that characterized hepatitis A incidence in the past have also essentially disappeared, presumably due, at least in part, to the implementation of vaccination recommendations.188,193 Since 2002, the county-level hepatitis A rates in the western states have been similar to those in other regions of the country.

Potential Sources of Infection

Currently, risk factor and exposure data for hepatitis A cases are often lacking in the United States. However, on the basis of the data from enhanced disease surveillance during 2005-2007, the most commonly reported exposure to HAV in the United States was international travel (accounting for 46% of cases), followed by household or sexual contact with hepatitis A cases (Fig. 176-12).194 Cases occurring among children and employees of child care centers and members of their households, which previously accounted for a substantial proportion of reports, were uncommon (8%), as were cases associated with common source food or water exposure (7%), illicit drug use (4%), and among men who had sex with men (MSM) (4%).194 It remains to be seen if cyclic outbreaks will continue to occur among MSM and users of injection and noninjection drugs.118,177,195–199 Historically during outbreak years, these exposures could account for 10% of nationally reported cases and, with the large decreases in incidence among children and their adult contacts, can now account for an even larger proportion of cases. Approximately half of hepatitis A cases reported through routine surveillance do not have a recognized source of infection,192,193 even with enhanced surveillance; one third will not have a source identified194 but may be contacts with persons, especially children, with asymptomatic infection.

Specific Groups and Settings

Child Care Centers, Schools, and Institutions

Outbreaks of hepatitis A in child care centers, which historically were a common occurrence, particularly in larger centers and in those that cared for children in diapers,200–202 are now rare,194 at least in part because of the routine vaccination of children against hepatitis A. However, the potential for transmission in these settings remains. Outbreaks in child care centers have occasionally been the source of more extensive transmission within a community,201,203,204 but in most cases disease in child care centers reflects disease transmission from the community. Similarly, hepatitis A cases among older children in schools usually reflect disease that has been acquired in the community, although multiple cases among children in a school may indicate a common source outbreak.205 Historically, HAV infection was endemic in institutions for the developmentally disabled, but with smaller facilities and improved conditions, the incidence and prevalence of infection have decreased and outbreaks are rarely reported in the United States.206

Users of Illicit Drugs

Outbreaks were regularly reported among illicit drug users in North America, Australia, and Europe in the 1990s and early 2000s.197,198,207–215 In the United States, these outbreaks frequently involved users of injected and noninjected methamphetamine and accounted for up to 30% of reported cases in these communities during outbreaks.118,198,209,216 HAV transmission attributable to injecting drug use has also decreased in the United States and, on the basis of enhanced surveillance during 2005-2007, accounted for less than 5% of reported cases.191,192

Cross-sectional serologic surveys previously demonstrated that injection drug users had a higher prevalence of anti-HAV than the general U.S. population.217,218 Transmission among injection drug users probably occurs through both the percutaneous and fecal-oral routes.209

Men Who Have Sex with Men

Hepatitis A outbreaks among men who have sex with men have been reported in urban areas in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia and may occur in the context of an outbreak in the larger community.* However, such outbreaks have rarely been detected in the United States in recent years.191,192 Seroprevalence surveys have not consistently demonstrated an elevated prevalence of anti-HAV compared with a similarly aged general population.218,223 Some studies conducted during outbreaks and seroprevalence surveys among men who have sex with men have identified specific sex practices associated with illness, whereas others have not demonstrated such associations.195,218,220

Transfusions and Other Health Care Settings

Transfusion-related hepatitis A is rare. The risk of infection in patients with hemophilia is not known, but results of a serologic survey of hemophiliac patients in the 1990s suggest that they may have been at increased risk,224 and outbreaks have been reported in Europe and the United States among patients who received factor VIII and IX concentrates.136,225 Outbreaks have also been reported in neonatal intensive care units after transmission to hospital staff from a neonate with asymptomatic HAV infection acquired from a blood transfusion.109,226,227 Transmission was also reported in association with an experimental treatment with lymphocytes incubated in serum from a donor with HAV infection.228

Nosocomial transmission from adult patients to health care workers is rare because most patients with hepatitis A are hospitalized after the onset of jaundice, when infectivity is low,106 but it has been reported in association with fecal incontinence of the patient.229,230 Health care workers have not been found to have an increased prevalence of anti-HAV compared with control populations in serologic surveys conducted in the United States.231

International Travel

Hepatitis A is a common infection among travelers from developed countries who travel to regions with high, transitional, or intermediate endemicity (see Fig. 176-6)232–234 and currently is the most common risk factor identified among reported hepatitis A cases in the United States.194 In prospective studies of American and European travelers, the risk of infection for those who did not receive IG was found to be 3 to 5 per 1000 per month of stay, of the same order of magnitude as that for malaria, 10 to 100 times greater than that for typhoid, and 1000 times greater than that for cholera.235,236 The risk may be higher among travelers staying in areas with poor hygienic conditions237 and varies according to the region and the length of stay. Travelers nevertheless should exercise caution regarding what they consume when anywhere in endemic countries. In the United States and Europe, hepatitis A in persons, especially children, traveling to endemic countries to visit relatives and friends accounts for an increasing proportion of reported cases.182,183,184,238,239 Compared with persons traveling for work or recreation, these individuals tend to have trips of longer duration and, by staying in family settings rather than hotels, may have greater exposure to HAV circulating in the community.240 Travelers who acquire hepatitis A during their trip may also transmit to others on their return. Cases of hepatitis A have been reported in nontraveling family members and close contacts of international adoptees after exposure to nonjaundiced adoptees from hepatitis A–endemic countries, resulting in U.S. recommendations for hepatitis A vaccination of these persons (see later).182,241–243

Foodborne and Waterborne

Foodborne hepatitis A outbreaks are recognized relatively infrequently in the United States.125 They are most commonly associated with contamination of food during preparation by a food handler with HAV infection.123,124,244,245 Implicated foods include those not cooked after handling, such as sandwiches and salads, as well as partially cooked foods.246–249 Food contaminated before retail distribution, such as lettuce or fruits contaminated at the growing or processing stage, has been increasingly recognized as the source of hepatitis A outbreaks.205,250–256,257 Waterborne hepatitis A outbreaks are rare and related to sewage contamination or inadequate treatment of water.258–260 Outbreaks associated with contaminated shellfish in this country are rare, but the occurrence of a multistate outbreak linked to oysters from the Gulf of Mexico in 2005 indicates that the potential for these types of transmission remains.73

Although the results of some serologic surveys conducted among sewage workers in Europe indicated a possible increased risk of HAV infection, findings have not been consistent.261–263 In published reports of three serologic surveys conducted among U.S. sewage workers and appropriate comparison populations, no substantial or consistent increase in prevalence of anti-HAV was found among sewage workers.264–266 No work-related instances of HAV transmission have been reported among sewage workers in the United States.

Pathogenesis

Although HAV shares many virologic characteristics with enteroviruses, it has several differentiating features that influence the pathogenesis and clinical expression of the disease. HAV is resistant to heat, solvents, and acid and grows slowly in living cells, where it has been shown to be relatively noncytolytic and to have little effect on the rate of host protein synthesis.

Incubation Period

Determination of the incubation period of disease is imprecise because the early symptoms of hepatitis are often vague and nonspecific. Jaundice may not be noticed by the patient, so the most useful marker of the onset of the disease is a change in urine color, which is almost always recognized by the patient and is the most common reason for seeking medical attention. The range of incubation is between 15 and 50 days, with a mean of approximately 28 days. Although HAV can be transmitted orally or parenterally, the incubation period is independent of the route of inoculation.267 Experiments in primates and observations in humans suggest that the incubation period is dependent on the infectious dose.268

Site of Viral Replication

HAV is generally transmitted by the fecal-oral route. Because the virus is acid resistant, it probably passes through the stomach, replicates lower in the intestine,269–271 and is then transported to the liver, which is the major site of replication.269,272,273 Evidence of replication in the oropharynx has been obtained in chimpanzees, and HAV has been identified in human saliva.115,116 HAV, like many other picornaviruses, is highly organ specific with little evidence of significant replication outside the liver. Virus is shed from infected liver cells into the hepatic sinusoids and canaliculi, passes into the intestine, and is excreted in feces. In humans and nonhuman primates, HAV has been detected in the liver, bile, and feces.274,275 The first indirect evidence that virus may replicate in the gut was the detection of co-proantibodies in the feces,276,277 followed by the demonstration of hepatitis A antigen in duodenal lining cells.269 Nonetheless, the major pathology is restricted to the liver.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree