(1)

State University of New York at Buffalo Kaleida Health, Buffalo, NY, USA

Occasionally, the axillary nodes are heavily involved by large, palpable nodal masses that invade the pectoral muscles and extend to the clavicle and to the lower cervical nodes above the clavicle. This extensive disease usually is accompanied by wide hematogenous dissemination to other organs, rendering surgical treatment inadvisable. There are situations, however, in which an extensive node dissection becomes a reasonable approach: when there is no detectable evidence of distant disease, there has been a long disease-free interval from the diagnosis of the primary tumor, the masses are becoming symptomatic, and there is no effective systemic therapy. The decision to operate becomes easier, of course, when there is no involvement of the neurovascular axillary bundle, manifesting itself with swelling of the arm or neurological symptoms in the distribution of one of the nerves of the brachial plexus. When the upper extremity becomes cyanotic, with diminished arterial pulse, clearly a limb-preserving resection is not possible, and the only surgical option remaining (particularly in cases of impending gangrene) is a forequarter amputation.

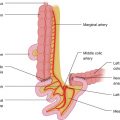

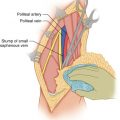

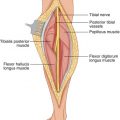

The technique of extensive lymphadenectomy includes an incision from the middle of the clavicle toward the lateral edge of the pectoralis major and then transversely, about two fingerbreadths below the axillary crease, to the border of the latissimus dorsi (Fig. 11.1). At the level of the axilla proper, flaps are developed superiorly and inferiorly, as described for axillary node dissection in Chap. 10 (Fig. 11.2). The development of the flaps over the pectoral muscles to the clavicle is wide enough that the palpably involved portion of these muscles may be divided by cautery around the tumor, so that it can be removed en bloc with the underlying nodal masses lying over the brachial plexus and axillary vessels (Fig. 11.3). The skin incision is extended along the clavicle on each side of the end of the axillary incision, forming a T, either at the beginning of the procedure (Fig. 11.1) or after a preliminary dissection through the long axillary incision. In the axillary area, a greater or lesser portion of the pectoralis major muscle is divided around the nodal masses infiltrating this muscle (Fig. 11.4). The pectoralis minor muscle is divided off its origin from the third to fifth ribs and at its insertion in the coracoid process, and the whole mass of muscles and nodes is dissected off the brachial plexus below the coracobrachialis muscle (Figs. 11.5 and 11.6). This plane of dissection, between the brachial plexus and axillary artery on one side and the lymph node masses on the other side, can be continued as long as the exposure remains adequate and the separation of the nodes is relatively easy (Fig. 11.7). Otherwise, one develops the superior flap from the transverse portion of the incision to the level of the midneck and dissects above the palpable cervical nodes, mobilizing them toward the axilla. The sternocleidomastoid muscle and the internal jugular vein may be removed if necessary. The omohyoid muscle is divided medially and laterally; the phrenic nerve is exposed in front of the scalenus anterior, and the brachial plexus trunks are dissected clean as they issue between the scalenus anterior and medius muscles. If the lymph nodes seem to extend behind the clavicle (an assessment that can be made more definitive by dissecting above and below the clavicle), then one should not hesitate to remove a sufficient portion of the middle of the clavicle to obtain the necessary exposure. A right angle clamp is passed around the clavicle, clinging on the undersurface of the bone to avoid incidental injury to the subclavian vessels. The bone, divided medially and laterally with a Gigli saw (Fig. 11.8), is left attached to the specimen. It should then be possible, by dissecting in an alternating fashion from the lower neck and axilla, to separate the nodal masses off the neurovascular bundle. The specimen is then mobilized inferior to the axillary vein (Fig. 11.9), and venous tributaries to the vein are ligated and divided (Fig. 11.10) while the long thoracic nerve (Fig. 11.11) and the thoracodorsal nerve are exposed and dissected free, if they are not involved by tumor (Fig. 11.12). Usually, with such extensive involvement of the axilla, one or both of these nerves need to be sacrificed.