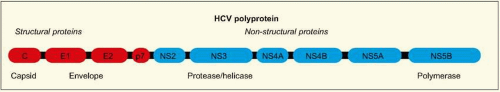

HCV is classified in the Flaviviridae family, although its genome is sufficiently distinct from related viruses to permit it to be placed in its own genus,

Hepacivirus (Table 2.1). The structure of

HCV is an enveloped ribonucleic acid (

RNA) virus contained in a roughly spherical particle approximately 50 nm in diameter. The

HCV genome is a positive-sense, single stranded

RNA molecule approximately 9.6 kb in

length, with highly conserved untranslated regions. There is a single large open reading frame of about 9 kb in length, which encodes a very large polyprotein (~3000 amino acid residues) (

Fig. 2.1). This protein undergoes co- and posttranslational processing by various viral and host cellular proteases to yield the individual structural and non-structural viral proteins. In an infected individual, more than 10 trillion

HCV particles are produced per day, even in the chronic phase of infection.

HCV exhibits considerable genetic diversity due to the presence of an

RNA polymerase that is deficient in proofreading ability. Over the course of infection, large numbers of similar, but distinct, strains of

HCV develop. These strains are known as quasispecies and are present in all HCV-infected persons. In addition, families of

HCV with more distinct genetic characteristics have also developed over long periods of time into six major and distinct families of

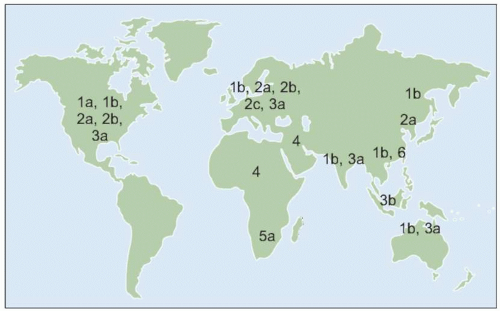

HCV known as genotypes.

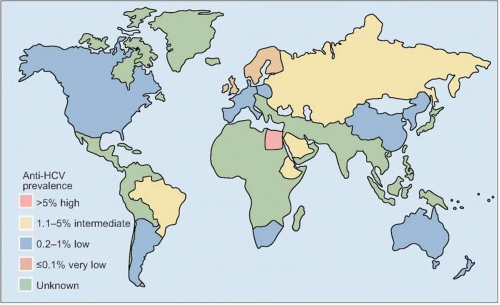

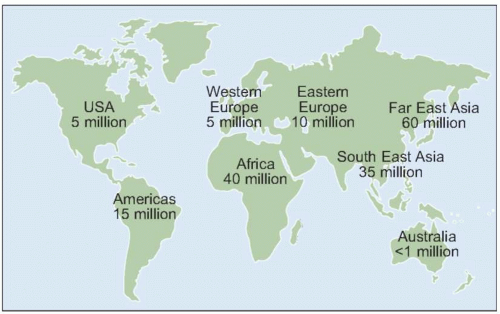

HCV genotype varies considerably in worldwide distribution and, in addition, has clinical implications for predicting response rates to currently available therapy (as discussed in more detail below).

The major target of

HCV infection and replication is the hepatocyte.

HCV RNA has been detected in several other cell types including B- and T lymphocytes, and monocytes; however, the significance of

HCV infection of these cell types is not well understood. The central theme of

HCV infection is that of viral persistence and, as such,

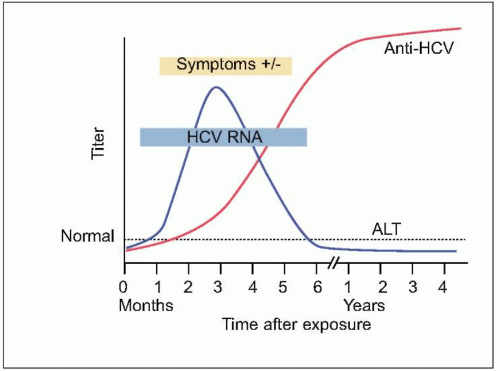

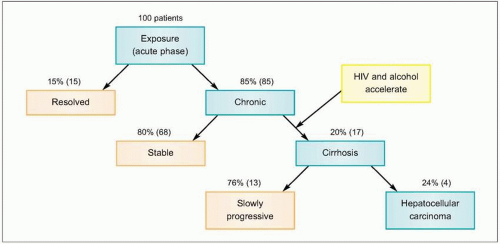

HCV infection causes little direct cytotoxicity to hepatocytes. In only a minority of individuals (~15%) is the host immune response able to clear

HCV infection (

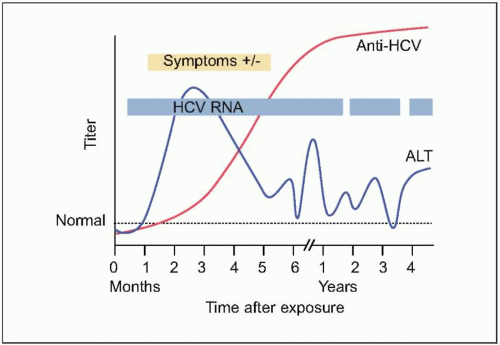

Figs. 2.2, 2.3). The majority of HCV-infected individuals (~85%) go on to develop persistent

HCV infection (

Figs. 2.3, 2.4). The efficiency of the innate and adaptive host immune responses determines whether the acute infection is cleared and, in those with chronic infection, the level of end organ cytotoxicity (i.e. clinical hepatitis) that occurs. The intensity of the host immune and inflammatory response may also be correlated with the risk of developing cirrhosis and/or

HCC late in the course of infection.

HCV has developed a variety of strategies to evade primary and adaptive immune responses by the host, allowing for persistent infection lasting up to 40 years or longer. Chronic

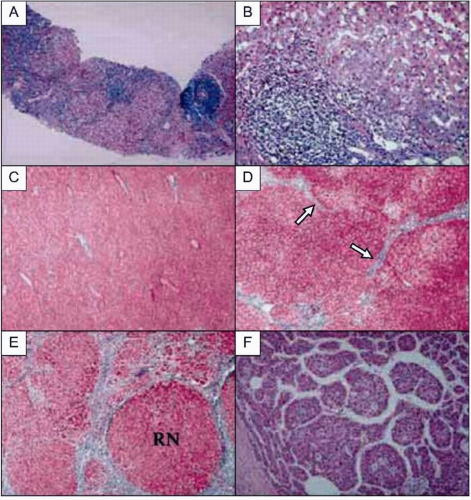

HCV infection causes persistent hepatic inflammation and promotes fibrosis, two pathophysiologic conditions that predispose infected individuals to develop cirrhosis and/or

HCC, the two most serious outcomes of chronic hepatitis C (

Figs. 2.3, 2.5).