Michael H. Augenbraun

Genital Skin and Mucous Membrane Lesions

Genital lesions are of uncertain historical pedigree. Ancient Chinese medical writings dating back to as early as 2500 bc appear to have alluded to a “corroding ulcer” of the genitals, developing a few days after coitus.1 There are references throughout the Old Testament to genital pathology that may have been infectious in nature. Ancient Greek, Roman, and Arabic medical texts also suggest a familiarity with acute genital infections, but the descriptions are difficult to associate with any specific clinical syndrome recognized today.2,3

Although genital lesions originate from a wide range of infectious processes, they most commonly result from sexually transmitted diseases or venereal infections (Table 108-1).4,5,6,7 Other pathologic processes, including chemical and mechanical trauma, neoplasia, and immunologic phenomena, also can cause genital lesions (Table 108-2). The term venereal, as it relates to disease, dates to the 15th century. Its root comes from the Latin venereus or venus, meaning “from sexual love or desire.” In the United States, the most common causes of sexually transmitted genital lesions are herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), Treponema pallidum (syphilis), and human papillomavirus (HPV).8

Infectious genital lesions are unique in a number of ways when compared with other infectious processes. Most are communicable and therefore are not only a clinical concern but also a public health concern. Infectious genital lesions can harbor more than one pathogen at a time, making proper diagnosis and management a challenge.9,10 The morphologic appearance of the lesion can differ widely from one clinical presentation to another, even when the causative organism is the same. The unpredictable nature of lesion presentation can make a purely clinical diagnosis unreliable.11–13 Inflammatory epithelial defects characteristic of these pathologies appear to enhance the transmission of other diseases, most importantly human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Genital lesions may contribute substantially to the worldwide spread of this infection.14–20

This chapter focuses on the broad issues relevant to the assessment and management of genital lesions. For in-depth discussions of individual pathogens, readers are directed to the chapters that address those topics.

History of Presentation

Individuals who present with a new genital lesion and who report recent sexual activity, particularly activity with a new partner or someone with a suspected genital infection, are likely to have a sexually transmitted infection. On the other hand, certain clinical circumstances suggest nonsexually transmitted pathology, such as trauma, chemical irritation, or allergic hypersensitivity. A lesion that occurs proximate to sexual exposure (i.e., within hours to 1 or 2 days) may be too early to account for the incubation period of most infectious pathologies. In the case of a lesion with rapid onset, the nature of the sexual activity, a topic often left unexplored by the clinician and patient, may suggest trauma.21,22 Traumatic genital lesions may result from sexual assault, questions about which are also often avoided.23 Recurrent lesions in someone who uses or whose partner uses latex condoms may be attributable to a latex allergy, although allergy typically results in more generalized edema and erythema of the genitals rather than a focal ulcer or papular lesion.24 The geographic prevalence of disease may be an important factor to consider when assessing a genital lesion in a traveler.

A history of recurrent genital lesions with or without dysesthesias preceding the development of lesions usually suggests an infection with HSV. HSV-2 and, less commonly, HSV-1 cause a chronic genital ulcer disease that is characterized by repeated symptomatic or often subclinical outbreaks separated by variable periods of quiescence during which the virus is localized to the dorsal root ganglia. A variety of factors are postulated to precipitate viral shedding, including immunosuppression, other intercurrent illnesses, sun exposure, and menses.25

Host factors can be important historical determinants of genital lesion etiology. Patients with preexistent psoriasis or eczema or other noninfectious dermatitides may have a genital lesion related to the underlying dermatologic pathology. Recent history of medication use, such as tetracyclines or antineoplastics in someone presenting with a new genital lesion, can prompt consideration of a fixed-drug eruption. In these cases, lesions may be characterized by pigmentation or superficial ulceration.26–30 Candidal balanitis in men has been associated with immunosuppression, contact with a partner who has vaginal candidiasis, and diabetes.29–33 Vulvovaginal candidiasis is an extremely common problem that may manifest as focal genital lesions.34 Although it may be more common in women with underlying immunosuppression (e.g., diabetes mellitus, HIV infection), vulvovaginal candidiasis occurs most frequently in women without such risk factors.35,36 Autoimmune diseases, such as acute reactive arthritis, Crohn’s disease, or Behçet’s syndrome, may be associated with genital lesions.37–41 The spectrum of typical and atypical genital lesions associated with HIV infection is broad: Kaposi sarcoma, giant condyloma acuminatum, chronic nonhealing HSV, and chancroid.42,43,44–46 This reflects both the common occurrence of coinfection with other sexually transmitted diseases and a propensity for HIV immunosuppression to modulate other conditions.

Clinical Manifestations

Location

In men, lesions associated with infectious or noninfectious processes may be found on or under the prepuce, around the coronal sulcus, on the shaft of the penis, the scrotum, the perianal tissue, the inner thighs, or the rectum. In the female patient, sites of involvement are equally varied. Genital lesions can appear on the mons pubis, labia, fourchette, cervix, inner thighs, perianal tissue, or anywhere in the vagina. As a result of orogenital sex, pathogens such as HSV and Treponema pallidum can also cause orolabial lesions. Lesions of chancroid can be disseminated distant from the genitalia and the original site of infection by a process of autoinoculation, although this is not common.47,48 In secondary syphilis, spirochetemia causes lesions, sometimes widely dispersed from the genitalia, that morphologically range from the classic papulosquamous rash of the palms and soles to the moist, raised lesions of condylomata lata (genitals) or mucous patches (orolabial area). Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a pathogen not commonly associated with genital lesions, may disseminate and cause tender, necrotic pustules, primarily on the distal extremities as part of an arthritis-dermatitis syndrome.49 Lesions associated with scabies infestation are common in the genital region as well as intertriginous areas elsewhere, including but not limited to the axillary folds and the interdigital spaces. Genital edema can occur after any local inflammatory process.50

Pain, Dysesthesias, and Systemic Symptoms

The lesions of syphilis, lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), scabies, molluscum contagiosum, and HPV are ordinarily painless. Herpetic lesions are usually painful, although they may not be noticed until the clinician examines the patient and palpates or abrades the lesion. If herpes lesions are adjacent to or within the urethra, the patient can experience dysuria. Pain or other dysesthesias, including pruritus, may precede the development of a clinically recognizable lesion, particularly during episodes of disease recurrence.51–53 The so-called prodromal symptoms are usually milder than those experienced during a primary outbreak. They may be so characteristic that patients can be reliably instructed to begin antiviral medication before lesions erupt. Chancroid ulcers are typically painful. Genital lesions from immunologically mediated noninfectious causes, such as Behçet’s syndrome, genital extensions of Crohn’s disease, aphthous ulcers, and vulvitis/vestibulitis, may also be exquisitely tender. Granuloma inguinale (donovanosis), a genital ulcer disease seen primarily in the tropics, is caused by the bacillus Klebsiella (Calymmatobacterium) granulomatis. Although the lesions of this disease are often large and destructive, pain is surprisingly absent. Most patients with exophytic genital warts are asymptomatic; a few may report pain or pruritus.

Pruritus is common only with ectoparasitic infestations such as scabies or lice. The pruritus associated with scabies is often described as intense and worse at night. Although pruritus may be experienced by individuals with herpes or syphilis, it is not characteristic of these conditions. Fever is occasionally seen with secondary syphilis and with primary herpes simplex infection, but usually is absent.53,54 Headaches, fatigue, myalgias, and malaise may also accompany these infections.

Lymphadenopathy

Inguinal lymphadenopathy is a nonspecific finding that is characteristic of inflammatory pathology almost anywhere in the groin or either lower extremity. It may also be a manifestation of systemic disease, such as HIV infection, tuberculosis, or lymphoma. It often accompanies genital infection. Although the inguinal and femoral lymph nodes drain the genital region in both men and women, the inner segment of the vagina and the cervix drain into deep pelvic and perirectal lymph nodes. Anorectal lymph drainage patterns are also complex and depend on whether infection occurs above or below the dentate line (the mucocutaneous junction in the rectum) In either case, if pelvic lymph nodes are involved in inflammatory genital pathology, pelvic or rectal discomfort may be the most striking symptom.

Bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy is typical in syphilis. Like the chancre of primary syphilis, it is usually painless. In secondary syphilis, as befitting a systemic process, lymphadenopathy distant from the genital area is common. Typically, the inguinal, axillary, cervical, and epitrochlear nodes are involved.54 Lymphadenopathy associated with a herpetic genital lesion is usually bilateral and, like the lesion, also is tender. In HSV infection and in syphilis, lymphadenopathy persists for some time after resolution of the lesion.

LGV and chancroid are characterized by expansive, tender lymph nodes called buboes. These may be unilateral or bilateral. A central area of fluctuance often develops; if left untreated, it eventually spontaneously ruptures. Although drainage may be spontaneous, tenderness can become sufficiently severe to warrant intervention and drainage. Lymphadenitis is unusual in granuloma inguinale.

Lesion Morphology

Although the appearance of a genital lesion is not entirely specific, it can implicate an etiologic agent. Herpes infections are characterized by vesicles that evolve into pustules and finally to shallow ulcers on an erythematous base (Fig. 108-1). Multiple lesions are common, and they may erupt in tightly grouped clusters. Sometimes the characteristic evolution of the lesion is not appreciated, and the patient or clinician simply observes tender ulcers that assume a wide variety of shapes and sizes because of confluence of evolving vesicles and pustules (Fig. 108-2). In a primary outbreak, lesions can reach sizes greater than 1 to 2 cm in diameter (Fig. 108-3). Immunocompromised individuals, such as transplantation patients, those taking immunosuppressive agents, and those infected with HIV can also experience extensive herpetic ulceration of the genitals in the setting of either a primary outbreak or a recurrence.45,55,56 At the other end of the spectrum, a substantial proportion of patients fail to recognize herpes outbreaks because of mild or absent symptoms.57 When instructed carefully about these types of outbreaks, most of these individuals can recognize disease.58

Syphilitic chancres are typically solitary, although they may rarely occur in pairs. They are round and 1 to 2 cm in diameter, with clean margins that are indurated on palpation (Fig. 108-4). The ulcer base usually lacks exudate but occasionally becomes superinfected with other bacteria.

The lesions of secondary syphilis are not chancre-like. They may start anywhere as fine macular lesions that evolve into pigmented papules, often with a fine, circumferential scale. In warm, moist areas such as the buttocks and genitals, unique lesions of secondary syphilis, known as condylomata lata, develop (Fig. 108-5). These are raised, moist nodules or plaques that are teeming with treponemes. They are highly infectious.

Chancroid lesions are similar in size to syphilitic chancres, but their edges are ragged and undermined (Fig. 108-6). The ulcer base is necrotic with a purulent exudate. Compared with the lesions of syphilis, induration of chancroid lesions tends to be less prominent, accounting for the designation of these ulcers as “soft chancres” (ulcus molle, chancre mou). Despite the obvious tissue damage, adjacent inflammation is absent. Single lesions are the norm, but multiple lesions may be seen.

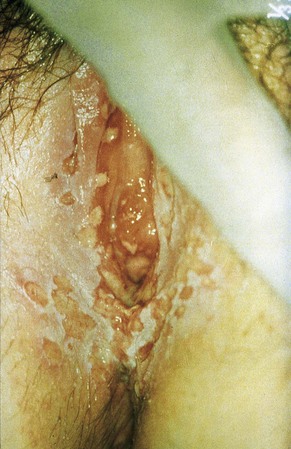

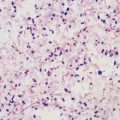

The lesions of granuloma inguinale start as firm subcutaneous nodules or papules that eventually ulcerate. Typically, this ulcerative process becomes hypertrophic and bleeds easily (Fig. 108-7).59 Local tissue destruction may be extensive. Swelling of the vulva and phimosis are common. Variants include deeply necrotic ulcers and dry, so-called cicatricial lesions that consist primarily of fibrotic tissue. On occasion, lesions are confused with squamous cell carcinoma.60

LGV (also called Nicholas-Durand-Favre disease) is one of several sexually transmitted diseases caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and is attributable specifically to serovars L1, L2, and L3. At its earliest stage, LGV may cause a small papule or herpes-like ulcer. This is usually asymptomatic and resolves before recognition.61 The patient with LGV then comes to medical attention with tender inguinal lymphadenopathy as the primary process of concern.

Clinically visible lesions of HPV are typically caused by viral types with low oncogenic potential (i.e., types 6 and 11). Most HPV infections are asymptomatic. Lesions can run the gamut from flat or relatively inconspicuous papules to verrucous, pedunculated, or large cauliflower-like masses referred to as condylomata acuminata (Fig. 108-8). Whatever the configuration, these lesions are clinically characteristic and unlikely to be confused with those of other etiologies. Certain HPV types (e.g., 16, 18, 31, and 33) have oncogenic potential both on moist mucosal surfaces such as ectocervix and, less commonly, on keratinized epithelium characteristic of the external genitalia. The dysplastic cytologic changes they induce are collectively referred to as squamous intraepithelial (SIL) neoplasia and may be benign or malignant. Squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, the vagina, the vulva, the penis, or the anus may arise from previous HPV infection. HPV-associated carcinoma in situ on keratinized epithelium may manifest as multiple papular lesions, referred to as bowenoid papulosis or, when it occurs as a single plaque, as Bowen’s disease. Erythroplasia of Queyrat is a variant of this process that involves the glans of the penis.

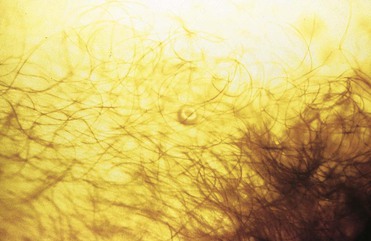

A poxvirus known as molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV) causes benign, wartlike lesions (Fig. 108-9). The etiologic agent of this condition is a member of the poxvirus family. Spread can be sexual or through nonsexual contact in children. Lesions are small, 3 to 5 mm in diameter, multiple, and clustered in the genital or inguinal areas, the perineum, or the inner thighs in adults. They appear pearly with an area of central umbilication, which often can be appreciated only on very close inspection. Lesions of scabies infestation range from papules to nodules with a surrounding crust (Fig. 108-10). With scratching, these lesions are often modified by excoriations or lichenification.

The use of systemic or topical antimicrobial agents before clinical evaluation can have a dramatic effect on lesion morphology.

Duration

Without therapy, herpes ulcers resolve within 3 weeks in cases of primary infection, and a recurrence resolves in 5 to 12 days. Except for some postinflammatory hypopigmentation, there is little scarring. Lesions that heal within days after an outbreak in the absence of therapy are probably not herpetic in nature. On the other hand, lesions proven to be herpetic and persist for longer than 3 to 4 weeks raise the possibility of underlying immunosuppression. Syphilitic chancres and condylomata lata also resolve without therapy, usually between 3 and 12 weeks and usually without much scarring. Without therapy, the lesions of chancroid and donovanosis are slowly destructive. Scarring is typical in both of these situations. Lesions caused by HPV or MCV may persist unchanged for a prolonged time, or they may be characterized by brief periods of clinical disease alternating with resolution.

Epidemiology

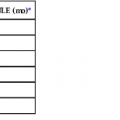

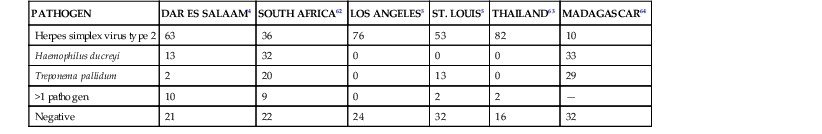

Understanding of the epidemiology of genital lesions has been hampered by inconsistent access to diagnostic tools in many parts of the world. The probability of a given cause of a genital lesion varies somewhat depending on the region of the world in which the patient lives or acquires infection (Table 108-3). Worldwide, HSV-2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease.

TABLE 108-3

Causes of Genital Ulcer Disease by Region (Percentage of Cases)

| PATHOGEN | DAR ES SALAAM4 | SOUTH AFRICA62 | LOS ANGELES5 | ST. LOUIS5 | THAILAND63 | MADAGASCAR64 |

| Herpes simplex virus type 2 | 63 | 36 | 76 | 53 | 82 | 10 |

| Haemophilus ducreyi | 13 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 |

| Treponema pallidum | 2 | 20 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 29 |

| >1 pathogen | 10 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 2 | — |

| Negative | 21 | 22 | 24 | 32 | 16 | 32 |

Although previously a common cause of genital ulcer in the developing world, chancroid has become increasingly rare.65,66 In the developed world, H. ducreyi is usually seen only in the context of focal urban outbreaks.67,68

In the absence of reliable serologic tests for HPV infection, it has been difficult to accurately determine the prevalence of this organism in different regions of the world. This assessment is further hampered by the asymptomatic nature of most infections. Despite these handicaps, some studies suggest that HPV may be the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States.69,70 Some of this infection results in the typical lesions of external genital warts known as condyloma acuminatum.71 The incidence of syphilis in the United States declined so precipitously through the 1990s that the U.S. Public Health Service embarked on an ambitious program to eliminate the disease from the country.72 Despite these efforts, outbreaks of early-stage syphilis, particularly among men who have sex with men (MSM) and who are also infected with HIV, have been reported.73 Even more dramatic increases in the incidence of syphilis have been seen in Europe.74–76

LGV occurs primarily in the tropics and subtropics.61,77 Sporadic cases and outbreaks of LGV occur in the developed world, and the disease should be considered in travelers returning from endemic areas.78–80 More recently, LGV outbreaks, characterized by ulcerative proctitis, have been noted among MSM in both Europe and North America.81–83 Donovanosis is endemic in Papua New Guinea but has also been seen in southern Africa, parts of India, the Caribbean, and South America. It is infrequently seen in the United States.59

Genital Lesions in Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Although the majority of HIV-infected individuals with genital lesions manifest disease in a fashion similar to their nonimmunocompromised counterparts, it is clear that some individuals, particularly those with significant immunosuppression, experience more extensive and prolonged disease. Large, persistent, or progressive condylomata acuminata have been well described in this patient population.84,85 In patients with HIV infection, the lesions of molluscum contagiosum can also vary in size and may number in the hundreds.86–88 In this population, both primary and recurrent herpetic ulcers may progress to extend over large areas of the perineum.45,89 The pain associated with such lesions can be so debilitating that it warrants hospitalization. Herpes lesions in HIV-infected individuals may persist well beyond the 2- to 3-week period ordinarily encountered in classic primary or recurrent disease. This finding may serve as an early sign of immunosuppression.90–92 There has also been concern that HIV-infected patients are more likely to harbor HSV isolates that are resistant to commonly used antiviral agents.93,94 The lesions of early-stage syphilis probably are not appreciably altered by HIV infection, although some data suggest that patients present more frequently than usual with multiple chancres. Clinical manifestations of secondary lesions may also develop before the resolution of the syphilitic chancre more commonly in HIV-infected individuals.95–97 Rarely, aggressive forms of secondary syphilis have been reported in patients with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.98,99 Whether this truly reflects an altered presentation in this population remains unclear. Anecdotal reports of accelerated disease and failure of routine therapy have not been supported by prospective studies.95

Any break in the ordinarily protective barrier of the integument, such as that caused by genital inflammatory lesions, can potentially serve as a conduit through which HIV is more efficiently transmitted from one sexual partner to another. Lesion exudate has been demonstrated to harbor virus.100–102 There is additional concern that genital HSV-2 may increase local HIV replication, further enhancing the risk of transmission.102 Syphilis, herpes, and chancroid infections have been associated with a greater likelihood of HIV infection in both retrospective and prospective studies.103–108

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree