4 Genetic Screening

Introduction

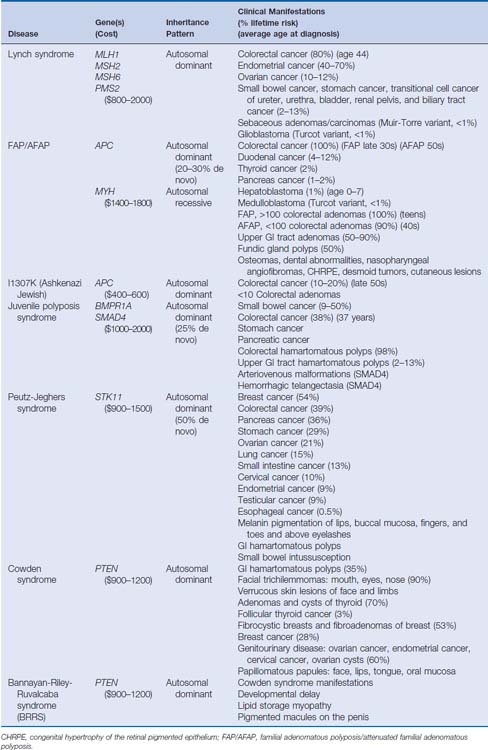

Over the past 20 years, tremendous strides have been made in understanding the molecular mechanisms of hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes. Genetic testing for many inherited colorectal cancer syndromes is clinically available and is becoming the standard of care in the management of these disorders. When used appropriately, genetic testing can provide opportunities for patients and at-risk family members to confirm a diagnosis, modify screening strategies, and adopt effective coping and management skills. Genetic testing also provides physicians with information regarding prognosis, surgical management, and the likelihood of response to chemotherapeutic agents. There are several hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes, and it is crucial to identify individuals who are at risk and who are appropriate for genetic testing (Table 4-1).

Proper Use of Clinical Genetic Testing

The annual incidence of colorectal cancer in the United States is approximately 146,970, causing 49,920 deaths per year.1 Most colorectal cancers—70% to 80%—are sporadic, meaning that they are caused by numerous environmental factors as well as genetic influences. About 10% to 20% of colorectal cancers are familial, meaning that affected individuals have two or more first- or second-degree relatives with colorectal cancer. Unfortunately, the cause of most familial colorectal cancers is not understood, and no clinically useful genetic testing is available.2 Only 5% to 10% of all colorectal cancers are hereditary and associated with a known gene(s) mutation. Therefore, most persons diagnosed with colorectal cancer are not appropriate for genetic testing.

Several organizations have policy statements concerning genetic testing, including the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the National Advisory Council of Human Genome Research, and the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA).3–5 Genetic testing is appropriate only for individuals who meet the following five criteria: (1) the family history or clinical history is suspicious for a hereditary cancer syndrome; (2) the person has a reasonable likelihood of carrying an altered cancer susceptibility gene; (3) the genetic test result is interpretable; (4) the genetic test result will influence medical management of the patient or the patient’s family members or is integral to reproductive decision making; and (5) the patient wants the information.

Genetic testing is a complex process, and the organizations producing policy statements on this topic emphasize the need for in-person pre- and post-test genetic counseling because of the clinical, psychosocial, and ethical issues raised throughout the testing process. Studies show that, without consultation with a genetic counselor or physician experienced with genetic testing, predictive and diagnostic genetic testing is often ordered and interpreted inappropriately.6 The National Society of Genetic Counselors maintains a directory of genetic counselors listed by geographic location, institution, and specialty (Box 4-1).

Box 4-1 Genetic Counseling and Testing Resources

National Society of Genetic Counselors

Maintains a list of genetic counselors by geographic location, institution, name, or specialty.

(206) 616-4033 www.genetsets.org

Can offer assistance to individuals diagnosed with cancer.

The Cancer Information Service (CIS)

The Genetic Counseling Process

The genetic testing strategy may be complex or very straightforward. If genetic testing involves a stepwise process, this should be explained along with a discussion of testing type, whether the test is for screening or diagnostic purposes, the timelines, and the cost. Also, identification of the most appropriate family member to begin testing should be determined. Genetic testing is most informative when starting with an affected family member to identify the specific family mutation. This strategy is important because most genetic tests are not 100% sensitive, and therefore the mutation search should start in an individual who appears affected. Once the family mutation is identified, this person serves as the positive control, and other family members can have predictive testing. Findings suggest that most individuals who undergo genetic testing had a previous diagnosis of cancer and are likely motivated to undergo testing to allow unaffected relatives predictive testing.7 If a specific mutation cannot be identified in an affected family member, the results are considered inconclusive and other unaffected at-risk family members cannot undergo genetic testing for the suspected syndrome.

Choosing a laboratory for genetic testing can be a complicated process, since most genetic tests are performed at only a few laboratories. Several aspects should be considered when choosing a laboratory. Most important, the laboratory should be Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)–certified. This organization continues to monitor quality control and reliability. Also, researching the laboratory’s testing options is necessary to determine whether the specific type of genetic testing essential to answering your patient’s clinical question is offered. Often, several methodologies are available for genetic testing of a particular gene. Some tests can be performed on only one type of sample (i.e., blood, tissue, amniotic fluid); other methods require the initial identification of the family mutation. Also, turn-around time and cost are of concern because some patients need the results quickly for medical management, whereas others, whose testing is not covered by insurance, would rather have testing at a slower, less expensive laboratory. Finally, support services offered by the laboratory, including interpretation of results, insurance billing, and insurance preauthorization should be understood.

Psychosocial issues vary from one patient to another, but the amount of patient distress usually depends on his or her motivation for testing. Research shows that the greatest distress occurs when testing is undertaken to help guide personal screening and surgical management.8 Some patients who test positive for a deleterious gene mutation are relieved to know the cause of their condition and thankful to be able to provide other at-risk family members with informative test results. Others are scared, angry, depressed, in denial, shocked, or feeling guilty about the potential of passing the mutation to the next generation. Patients who test negative usually feel relief and happiness; however, others may have survivor’s guilt, for being the family member pardoned from the disease, or mutation regret, the sense of lost opportunities by having lived life as though affected. Patients who receive inconclusive results (i.e., “no mutation found” in absence of a family mutation) are usually unsatisfied, whereas others have a false sense of security because a definitive mutation was not identified. Genetic testing also has health implications for other family members. Therefore, this issue should be addressed in detail with patients, noting the possibility of changing family dynamics.

Providing resources for families undergoing genetic testing affords patients with further support and information to cope with a diagnosis, decide about genetic testing, and select a management plan that works best for their personal situation. Genetic counselors often facilitate the patient’s entry into clinical trials, research studies, and support groups, and even connect them with other patients in similar situations. Numerous organizations are available to provide patient resources regarding cancer diagnosis, hereditary cancer syndromes, genetic testing, and research opportunities (see Box 4-1).

Genetic discrimination, though not seen frequently, can occur with health, life, or disability insurance and in the workplace. In 1997, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) was established to protect the patient’s personal information. HIPAA also has a provision against genetic discrimination. The law states that as long as the patient is part of a group health insurance plan he or she cannot be dropped from health insurance because of personal genetic test results, and individual insurance premiums cannot be increased because of genetic test results. Also, many states have supplemental laws governing genetic discrimination and health insurance. HIPAA does not provide protection for health insurance purchased in the individual market, small group plans (fewer than 50 individuals and self-administered), life, or disability insurance. Some states have legislation governing genetic discrimination of life, disability, and long-term care insurance. Most recently, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) of 2008 (P.L. 110–233, 122 Stat. 881), was signed into law. GINA is a federal law that prohibits discrimination in health coverage and employment based on genetic information (Box 4-2). GINA, together with HIPAA, prohibits health insurers from requiring genetic information of an individual or the individual’s family members or using it for decisions regarding coverage, rates, or preexisting conditions. The law also prohibits most employers from using genetic information for hiring, firing, or promotion decisions and for any decisions regarding terms of employment.

Box 4-2 Genetic Discrimination Resources

National Conference of State Legislatures

Genetic and Health Insurance State Anti-Discrimination Laws

www.ncsl.org/program/health/genetics/ndishlth.htm

National Conference of State Legislatures

Genetics and Life, Disability and Long-term Care Insurance

www.ncsl.org/program/health/genetics/ndislife.htm

United States Department of Health and Human Services

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (GINA)

http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi=bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=110_cong_public_laws&docid=f:publ233.110.pdf

Informed consent is one of the most important aspects of genetic testing. ASCO created 12 aspects of informed consent that must be achieved before genetic testing (Box 4-3). Most important, the risks, benefits, and limitations of the test must be described to the patient, including the potential implications of a positive, negative, or inconclusive test result and alternatives to genetic testing (Box 4-4). Written informed consent is obtained from adults or parents for their children. Genetic testing of individuals under age 18 is performed only when the hereditary cancer syndrome suspected requires screening and management before age 18.