- Diabetic foot problems remain the most common cause of hospital admissions amongst patients with diabetes in Western countries.

- Up to 50% of older patients with type 2 diabetes have risk factors for foot problems.

- Up to 85% of lower limb amputations are preceded by foot ulcers.

- All patients with diabetes should be screened for risk of foot problems on an annual basis: those with risk factors require regular podiatry, patient education and instruction in self-foot care.

- Most foot ulcers should heal if pressure is removed from the ulcer site, the arterial circulation is sufficient and infection is managed and treated aggressively.

- Any patient with a warm unilateral swollen foot without ulceration should be presumed to have an acute Charcot neuroarthropathy until proven otherwise.

Introduction

“Superior doctors prevent the disease. Mediocre doctors treat the disease before evident. Inferior doctors treat the full-blown disease” [Huang Dee, China, 2600 BC]

The Chinese proverb suggests that inferior doctors treat the full-blown disease, and until recent years, this was sadly the case with diabetic foot disease. Realizing the global importance of diabetic foot disease, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) focused on the diabetic foot throughout the year 2005, during which there was a worldwide campaign to “put feet first” and highlight the all too common problem of amputation amongst patients with diabetes throughout the world. To coincide with World Diabetes Day in 2005, The Lancet launched an issue almost exclusively dedicated to the diabetic foot: this was the first time that any major non-specialist journal had focused on this worldwide problem; however, major challenges remain in getting across important messages relating to the diabetic foot:

Much progress in our understanding of the pathogenesis and management of the diabetic foot has been made over the last quarter century. This has been matched by an increasing number of publications in peer-reviewed journals. Taken as a percentage of all PubMed listed articles on diabetes, those on the diabetic foot have increased from 0.7% in the 1980–1988 period to more than 2.7% in the years 1998–2004 [3]. Prior to 1980, little progress had been made in the previous 100 years despite the fact that the association between gangrene and diabetes was recognized in the mid-19th century [5]. For the first 100 years following these descriptions, diabetic foot problems were considered to be predominantly vascular and complicated by infection. It was not until during the Second World War, for example, that McKeown performed the first ray excision on a patient with diabetes and osteomyelitis but good blood supply: this was performed under the encouragement of Lawrence, who had diabetes himself and was co-founder of the British Diabetic Association, now Diabetes UK [6].

In the last two decades many major national and international societies were formed including diabetic foot study groups and the international working group on the diabetic foot was established in 1991. New editions of two leading international textbooks on the diabetic foot have been published in recent years [7,8], and a number of collaborative research groups are now tackling many of the outstanding problems regarding the patho-genesis and management of diabetic foot disease.

In this chapter, the global term “diabetic foot” will be used to refer to a variety of pathologic conditions that might affect the feet of people with diabetes. Initially, the epidemiology and economic impact of diabetic foot disease are discussed, followed by the contributory factors that result in diabetic foot ulceration. The potential for prevention of these late sequelae of neuropathy and vascular disease are discussed, followed by a section on the management of foot ulcers. The chapter closes with a brief description of the pathogenesis and management of Charcot neuroarthropathy, an end-stage complication of diabetic neuropathy. Throughout, cross-referencing will be provided to other chapters that also cover aspects of diabetic foot disease, particularly those on diabetic neuropathy (see Chapter 38), peripheral vascular disease (see Chapter 43), bone and rheumatic disorders in diabetes (see Chapter 48) and infection (see Chapter 50).

Epidemiology and economic aspects of diabetic foot disease

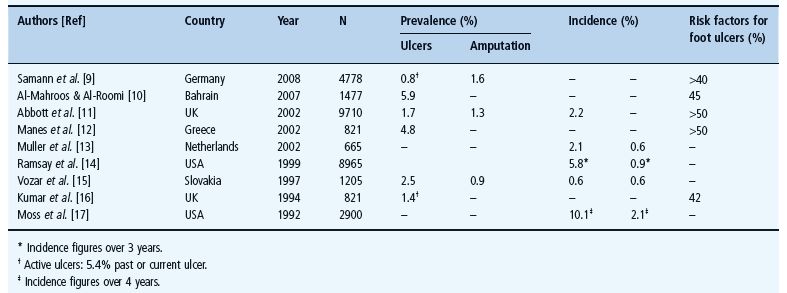

As foot ulceration and amputation are closely inter-related in diabetes [2], they will be considered together in this section. A selection of epidemiologic data for foot ulceration and amputation, originating from studies from a number of different countries [9–17], is provided in Table 44.1. Globally, diabetic foot complications remain major medical, social and economic problems that are seen in all types of diabetes and in every country [18]; however, the reported frequencies of amputation and ulceration vary considerably as a consequence of different diagnostic criteria used as well as regional differences [19]. Diabetes remains a major cause of non-traumatic amputation across the world with rates being as much as 15 times higher than in the non-diabetic population.

Table 44.1 Epidemiology of foot ulceration and amputation.

Although many of the studies referred to and listed in Table 44.1 were well conducted, methodologic issues remain which make it difficult to perform direct comparisons between studies and/or countries. First, definitions as to what constitutes a foot ulcer vary and, secondly, surveys invariably include only patients with previously diagnosed diabetes, whereas in type 2 diabetes, foot problems may be the presenting feature. In one study from the UK, for example, 15% of patients undergoing amputation were first diagnosed with diabetes on that hospital admission [20]. Third, reported foot ulcers are not always confirmed by direct examination by the investigators involved in the study. Finally, as can be seen from the table, in those studies that assess the percentage of the population that had risk factors for foot ulceration, 40–70% of patients fell into that category. Such observations clearly indicate the need for all diabetes services to have a regular screening program to identify such high risk individuals.

Health economics of diabetic foot disease

In addition to causing substantial morbidity and even mortality, foot lesions in patients with diabetes additionally have substantial economic consequences.

Diabetic foot ulceration and amputations were estimated to cost US health care payers $10.9 billion in 2001 [21,22]. Corresponding estimates from the UK based upon similar methodology suggested that the total annual costs of diabetes-related foot complications was £252 million [23]; however, similar problems to those noted with epidemiology exist when comparing data on the costs of diabetic foot lesions relating to methodology but also as to whether direct and indirect costs were included. Moreover, few studies have estimated costs of the long-term follow-up of patients with foot ulcers or amputations [2].

The most recent data from the USA suggest that in 2007 $18.9 billion was spent on the care of diabetic foot ulcers, and $11.7 billion on lower extremity amputations [24]. Having estimated the total cost of diabetic foot disease to be $30.6 billion in 2007, the authors went on to estimate the potential savings based upon realistic reductions in ulceration and amputation, to be as high as $21.8 billion. Such strong economic arguments may help to drive improvements in preventative foot care which could potentially lead to significant savings for health care systems.

Etiopathogenesis of diabetic foot lesions

“Coming events cast their shadow before.” [Thomas Campbell]

If we are to be successful in reducing the high incidence of foot ulcers and ultimately amputation, a thorough understanding of the pathways that result in the development of an ulcer is increasingly important. The words of the Scottish poet, Thomas Campbell, can usefully be applied to the breakdown of the diabetic foot. Ulceration does not occur spontaneously: rather it is the combination of causative factors that result in the development of a lesion. There are many warning signs or “shadows” that can identify those at risk before the occurrence of an ulcer. It is not an inevitable consequence of having diabetes that ulcers occur: ulcers invariably result from an interaction between specific pathologies in the lower limb and environment hazards. The breakdown of the diabetic foot traditionally has been considered to result from an interaction of peripheral vascular disease (PVD), peripheral neuropathy and some form of trauma. Other causes are also briefly described.

Peripheral vascular disease

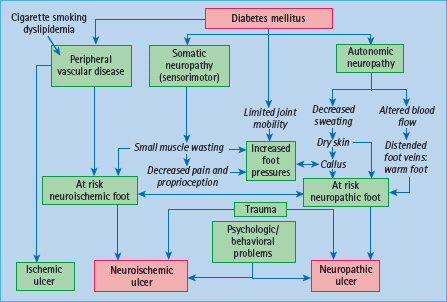

Although described in detail in Chapter 43, brief mention of the role of PVD in the genesis of foot ulcers must be made here. PVD tends to occur at a younger age in patients with diabetes and is more likely to involve distal vessels. Reports from the USA and Finland have confirmed that PVD is a major contributory factor in the pathogenesis of foot ulceration and subsequent major amputations [25,26]. In the pathogenesis of ulceration, PVD itself in isolation rarely causes ulceration: as will be discussed for neuropathy, it is the combination of risk factors with minor trauma that inevitably leads to ulceration (Figure 44.1). Thus, minor injury and subsequent infection increase the demand for blood supply beyond the circulatory capacity and ischemic ulceration and the risk of amputation ensues. In recent years, neuroischemic ulcers in which the combination of neuropathy and PVD exists in the same patient, together with some form of trauma, are becoming increasingly common in diabetic foot clinics.

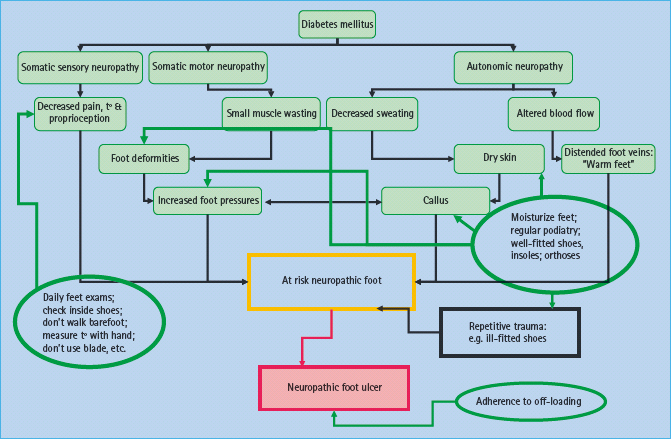

Figure 44.1 Pathways to foot ulceration in diabetes. Reproduced from Boulton et al. [7], with permission.

Diabetic neuropathy

As discussed in Chapter 38, the diabetic neuropathies represent the most common form of the long-term complications of diabetes, affect different parts of the nervous system and may present with diverse clinical manifestations [27]. Most common amongst the neuropathies are chronic sensorimotor distal symmetrical polyneuropathy and the autonomic neuropathies. It is the common sensorimotor neuropathy together with peripheral autonomic sympathetic neuropathy that together have an important role in the pathogenesis of ulceration.

Sensorimotor neuropathy

As noted in Chapter 38, this type of neuropathy is very common and it has been estimated that up to 50% of older patients with type 2 diabetes have evidence of sensory loss on clinical examination and therefore must be considered at risk of insensitive foot injury [27]. This type of neuropathy commonly results in a sensory loss confirmed on examination by a deficit in the stocking distribution to all sensory modalities: evidence of motor dysfunction in the form of small muscle wasting is also often present. While some patients may give a history (past or present) of typical neuropathic symptoms such as burning pain, stabbing pain, paresthesia with nocturnal exacerbation, others may develop sensory loss with no history of any symptoms. Other patients may have the “painful-painless” leg with spontaneous discomfort secondary to neuropathic symptoms but who on examination have both small and large fiber sensory deficits: such patients are at great risk of painless injury to their feet.

From the above it should be clear that a spectrum of symptomatic severity may be present with some patients experiencing severe pain and at the other end of the spectrum, patients who have no spontaneous symptoms but both groups may have significant sensory loss. The most challenging patients are those who develop sensory loss with no symptoms because it is often difficult to convince them that they are at risk of foot ulceration as they feel no discomfort, and motivation to perform regular foot self-care is difficult. The important message is that neuropathic symptoms correlate poorly with sensory loss, and their absence must never be equated with lack of foot ulcer risk. Thus, assessment of foot ulcer risk must always include a careful foot examination after removal of shoes and socks, whatever the neuropathic history [27].

The patient with sensory loss

A reduction in neuropathic foot problems will only be achieved if we remember that those patients with insensitive feet have lost their warning signal – pain – that ordinarily brings patients to their doctors. Thus, the care of a patient with sensory loss is a new challenge for which we have no training. It is difficult for us to understand, for example, that an intelligent patient would buy and wear a pair of shoes three sizes too small and come to the clinic with extensive shoe-induced ulceration. The explanation is simple: with reduced sensation, a very tight fit stimulates the remaining pressure nerve endings and is thus interpreted as a normal fit – hence the common complaint when we provide patients with custom-designed shoes that “these shoes are too loose”. We can learn much about the management of such patients from the treatment of patients with leprosy [28]. Although the cause of sensory loss is very different from that in diabetes, the end result is the same, thus work in leprosy has been very relevant to our understanding of the pathogenesis of diabetic foot lesions. It was Brand (1914–2003) who worked as a surgeon and a missionary in South India, who described pain as “God’s greatest gift to mankind” [29]. He emphasized the power of clinical observation to his students and one remark of his that was very relevant to diabetic foot ulceration was that any patient with a plantar ulcer who walks into the clinic without a limp must have neuropathy. Brand also taught us that if we are to succeed, we must realize that with loss of pain there is also diminished motivation in the healing of, and prevention of, injury.

Peripheral sympathetic autonomic neuropathy

Sympathetic autonomic dysfunction of the lower limbs leads to reduced sweating and results in both dry skin that is prone to crack and fissure, and to increased blood flow (in the absence of large vessel obstructive PVD) with arteriovenous shunting leading to the warm foot. The complex interactions of the neuropathies and other contributory factors in the causation of foot ulcers are summarized in Figure 44.1.

Other risk factors

Of all the other risk factors for ulceration (Table 44.2) one of the most important is a past history of similar problems. In many series this has been associated with an annual risk of re-ulceration of up to 50%.

Table 44.2 Factors increasing risk of diabetic foot ulceration. More common contributory factors shown in bold.

Peripheral neuropathy

Past history of foot ulcers Other long-term complication

Foot deformity Edema Ethnic background Poor social background |

Other long-term complications

Patients with other late complications, particularly nephropathy, have been reported to have an increased foot ulcer risk. Those most at risk are patients who have recently started dialysis as treatment of their end-stage renal disease [30]: It must also be remembered that those patients with renal transplants and more recently combined pancreas–renal transplants are usually at high risk of ulceration even if normoglycemic as a result of the pancreas transplant.

Plantar callus

Callus forms under weight-bearing areas as a consequence of dry skin (autonomic dysfunction), insensitivity and repetitive moderate stress from high foot pressure. It acts as a foreign body and causes ulceration [31]. The presence of callus in an insensate foot should alert the physician that this patient is at high risk of ulceration, and callus should be removed by the podiatrist or other trained health care professional.

Elevated foot pressures

Numerous studies have confirmed the contributory role that abnormal plantar pressures play in the pathogenesis of foot ulcers [3,32].

Foot deformity

A combination of motor neuropathy, cheiroarthropathy and altered gait patterns are thought to result in the “high risk” neuropathic foot with clawing of the toes, prominent metatarsal heads, high arch and small muscle wasting (Figure 44.2).

Figure 44.2 The high risk neuropathic diabetic foot demonstrating high arch, prominent metatarsal heads, clawing of toes and callus under first metatarsal head.

Ethnicity and g ender

The male sex has been associated with a 1.6-fold increase of ulcers [11]. With respect to ethnic origin, data from cross-sectional studies in Europe suggests that foot ulceration is more common in Europid subjects than other racial groups: for example, the North-West Diabetes Foot Care Study in the UK showed that the age-adjusted prevalence of diabetic foot ulcers (past or present) for Europeans, South Asians and African-Caribbeans was 5.5%, 1.8% and 2.7%, respectively [33]. Reasons for these ethnic differences certainly warrant further investigation. In contrast, in the southern USA, ulceration was much more common in Latino Americans and Native Americans than in White people of Northern European ancestry [34]; however, more recent data confirmed this increased risk in Latinos, despite the foot pressures being actually lower in this group [35].

Pathway to ulceration

It is the combination of two or more risk factors that ultimately results in diabetic foot ulceration (Figure 44.1). Both Pecoraro et al. [25] and later Reiber et al. [36] have taken the Rothman model for causation and applied this to amputation and foot ulceration in diabetes. This model is based upon the concept that a component cause (e.g. neuropathy) is not sufficient in itself to lead to ulceration, but when the component causes act together, they result in a sufficient cause which will inevitably result in ulceration. Applying this model to foot ulceration, a small number of causal pathways were identified: the most common triad of component causes, present in nearly two out of three incident foot ulcer cases, was neuropathy, deformity and trauma. Edema and ischemia were also common component causes. Other simple examples of two component causeways to ulceration are loss of sensation and mechanical trauma such as standing on a nail, wearing shoes that are too small; or neuropathy and thermal trauma (e.g. walking on hot surfaces or burning feet in the bath); finally, neuropathy and chemical trauma may result in ulceration from the inappropriate use for example of chemical “corn cures.” Similarly, this model can be applied to neur-oischemic ulcers where the three component causes comprising ischemia, trauma and neuropathy are often seen.

Prevention of diabetic foot ulcers

Screening

It has been estimated that the vast majority of foot ulcers are potentially preventable, and the first step in prevention is the identification of the “at risk” population. Many countries have now adopted the principle of the “annual review” for patients with diabetes, whereby every patient is screened at least annually for evidence of diabetic complications. Such a review can be carried out either in the primary care center or in a hospital clinic.

A taskforce of the American Diabetes Association recently addressed the question of what should be included for the annual review in the “comprehensive diabetic foot examination (CDFE)” [37]. The taskforce addressed and concisely summarized the recent literature in this area and recommended, where possible using evidence-based medicine, what should be included in the CDFE for adult patients with diabetes. Whereas a brief history was regarded as important, a careful examination of the foot including assessing its neurologic and vascular status was regarded as essential. There is a strong evidence base to support the use of simple clinical tests as predictors of risk of foot ulcers [11,37]. A summary of the key components of the CDFE is provided in Table 44.3. Whereas each potential simple neurologic clinical test has advantages and disadvantages, it was felt that the 10-g monofilament had much evidence to support its use hence the recommendation that assessment of neuropathy should comprise the use of a 10g monofilament plus one other test. In addition to those simple tests listed in Table 44.3, one possible test for neuropathy was assessment of vibration perception threshold. Although this is a semi-quantitative test of sensation, it was included as many centers in both Europe and North America have such equipment. As can be seen from Table 44.3, this is not regarded as essential, but strong evidence does support the use of vibration perception threshold as an excellent predictor of foot ulceration [38,39].

Table 44.3 Key components of the diabetic foot examination.

Inspection Evidence of past/present ulcers? Foot shape?

|

Dermatologic?

|

Neurologic 10-g monofilament at four sites on each foot + 1 of the following:

|

| Vascular Foot pulses Ankle brachial index, if indicated |

With respect to the vasculature, the ankle brachial index was recommended although it was realized that many centers in primary care may not be able to perform this in day-to-day clinical practice.

Intervention for high-risk patients

Any abnormality of the above screening test would put the patient into a group at higher risk of foot ulceration. Potential interventions are discussed under a number of headings, the most important of which is education.

Education

Previous studies have suggested that patients with foot ulcer risk lack knowledge and skills and consequently are unable to provide appropriate foot self-care [40]. Patients need to be informed of the risk of having insensate feet, the need for regular self-inspection, foot hygiene and chiropody/podiatry treatment as required, and they must be told what action to take in the event of an injury or the discovery of a foot ulcer. Recent studies summarized by Vileikyte et al. [41,42] suggests that patients often have distorted beliefs about neuropathy, thinking that this is a circulatory problem and link neuropathy directly to amputation. Thus, an education program that focuses on reducing foot ulcers will be doomed to failure if patients do not believe that foot ulcers precede amputations. It is clear that much work is required in this area if appropriate education is to succeed in reducing foot ulcers and subsequently amputations. The potential for education and self-care at various points on the pathway to neuropathic ulceration is shown in Figure 44.3.

Figure 44.3 The potential for education and self-care in prevention of neuropathic foot ulcers. t°, temperature. Courtesy of L. Vileikyte MD, PhD.

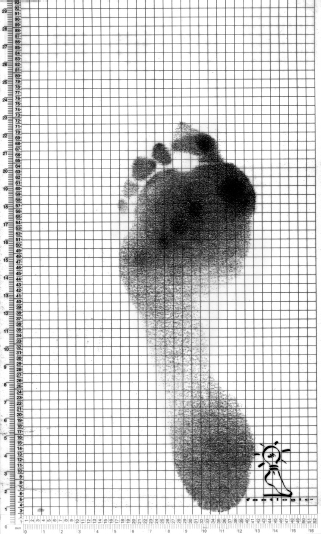

There have been a small number of reports that assess educational interventions, but these have mostly been small single-center studies. In the most recently published study, even though the foot care education program was followed by improved foot care behavior, there is no evidence that such targeted education was associated with a reduced incidence of recurrent foot ulcers [43]. It has been suggested that patients find the concept of neuropathy difficult to understand: they are reassured because they have no discomfort or pain in their feet. It may be that using visual aids (which can also be used for diagnosis of the at risk foot) may help patients to understand that there is something different about their feet compared with their partner’s, for example. This might include the use of the administered indicator plaster (Neuropad): when applied to the foot this changes color from blue to pink if there is normal sweating [44]. The absence of sweating such as in a high risk foot, results in no color change enabling patients to see that there is something different about their feet. A similar visual aid is the PressureStat (Podotrack) (Figure 44.4) [45]. This is a simple inexpensive semi-quantitative footprint mat that is able to identify high plantar pressures. The higher the pressure, the darker the color of the footprint. Similarly, this can be used as an educational aid and might help the patient realize that specific areas under their feet are at particular risk of ulceration.

Figure 44.4 A black and white pressure distribution of one footstep using PressureStat: the darkest areas represent highest pressures, in this case under metatarsal heads 1 and 3 and the hallux.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree