Face and Neck Syndromes

Cervical Adenitis and Adenopathy

Cervical adenitis is defined as enlarged, tender lymph nodes in the neck. Unilateral acute cervical adenitis is usually caused by a pyogenic bacterium.1 Involvement of the anterior cervical (tonsillar) nodes under the angle of the jaw suggests a tonsillar disease. The submandibular nodes may be involved. Enlargement of the posterior cervical nodes behind the sternocleidomastoid muscle is more likely to be associated with infectious mononucleosis.

The diagnosis should be cervical adenopathy if there is no erythema over the node and no tenderness. Many patients without such evidence of local inflammation have an infectious cause of the adenopathy, but many noninfectious diseases also result in cervical adenopathy.

Acute Unilateral Cervical Adenitis

A practical approach to cervical adenitis is to divide it into acute febrile unilateral cervical adenitis and all other forms. Acute unilateral cervical lymphadenitis can be empirically treated with oral antibiotics active against the two most likely etiologic agents, Staphylococcus aureus and Group A streptococci (such as dicloxacillin, cephalexin, or amoxicillin/clavulanate). Some improvement in clinical symptoms should take place within 48 hours, and ultimately most patients are cured, especially if they are seen early in the illness. However, a small proportion of patients will not respond, especially if the swelling appeared rapidly or is already large, and will continue to have an enlarging node. For such patients, oral antibiotic therapy on an outpatient basis usually does not produce a cure, and it is necessary to hospitalize them.

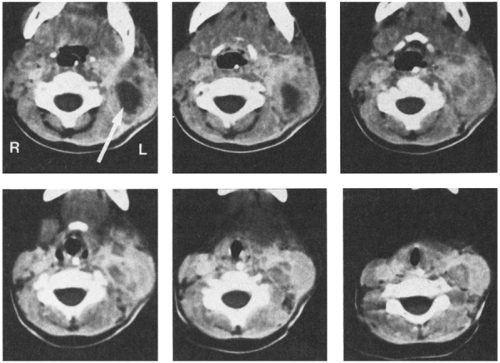

After hospitalization, an intravenous antibiotic such as nafcillin or clindamycin can be given for approximately 24–48 hours. During this time, the surrounding inflammatory process typically becomes less prominent, and the node will feel firmer and harder. Although the feeling of the node does not suggest that it is compressible or fluctuant, the tenseness of the node is probably caused by pus under pressure. Within the node is a variable area of liquefaction (Fig. 6-1) surrounded by an intensely inflammatory process with firmness secondary to infiltration of cells. Ultrasound may help define the process.

After about 24–48 hours of antibiotic therapy, it is often appropriate to do an incision and drainage of the lymph nodes, usually with a drain left in. The infecting organism may grow out of a culture of pus, as it may not be eliminated by antibiotic therapy, even if it is sensitive to the drug that was administered.

With this approach, most patients will have a short hospital stay and minimal complications. Once the fever is reduced by intravenous antibiotics, and after incision and drainage has been done and the drain removed in a day or so, healing usually occurs rapidly. The patient can then be discharged on oral antibiotics.

The management of other kinds of cervical adenitis is different and depends on whether the disease is chronic or subacute.

Infectious Etiologies

There is overlap between the causes of cervical adenitis and adenopathy, as the bacteria that can cause adenitis can also cause adenopathy, particularly if the findings are made milder by previous antibiotic therapy or by partial immunity of the patient. Thus Group A streptococci, one of the most frequent causes of cervical adenitis, is also a common cause of cervical adenopathy, which is usually bilateral. Infectious causes of cervical adenitis or adenopathy, in approximate order of frequency, are shown in Box 6-1.

Group A Streptococci and Staphylococcus Aureus

Determining whether Group A streptococci or staphylococci are the most common cause of acute

unilateral cervical lymphadenitis is fraught with difficulty. It is generally agreed that approximately 65–90% of all cases are due to one or the other. One series suggested that the incidence of Group A streptococcus and S. aureus was nearly identical.2 In a series of children who had not received antibiotics, Group A streptococci were the most frequent cause of cervical adenitis, as demonstrated by culture of the organism by needle aspiration, incision and drainage of the fluctuant nodes, or rising antistreptolysin O titers.3 In some cases, S. aureus was recovered from the node, by itself, or in concert with Group A streptococcus, and an antibody response to Group A streptococcus was demonstrated. Another series ranked beta-hemolytic streptococci second to S. aureus regardless of prior antibiotic therapy.4 Throat culture is not necessarily predictive of the infecting organism; some patients have positive throat cultures for Group A streptococcus when the lymphadenitis is due to S. aureus; sometimes, beta-hemolytic streptococci are not recovered from the throat, even though the organism is recovered by needle aspiration of the node.3,4 Published studies may underestimate the frequency of Group A streptococcus, as these children tend to recover after simple antibiotic therapy and thus not go on to drainage and culture.

unilateral cervical lymphadenitis is fraught with difficulty. It is generally agreed that approximately 65–90% of all cases are due to one or the other. One series suggested that the incidence of Group A streptococcus and S. aureus was nearly identical.2 In a series of children who had not received antibiotics, Group A streptococci were the most frequent cause of cervical adenitis, as demonstrated by culture of the organism by needle aspiration, incision and drainage of the fluctuant nodes, or rising antistreptolysin O titers.3 In some cases, S. aureus was recovered from the node, by itself, or in concert with Group A streptococcus, and an antibody response to Group A streptococcus was demonstrated. Another series ranked beta-hemolytic streptococci second to S. aureus regardless of prior antibiotic therapy.4 Throat culture is not necessarily predictive of the infecting organism; some patients have positive throat cultures for Group A streptococcus when the lymphadenitis is due to S. aureus; sometimes, beta-hemolytic streptococci are not recovered from the throat, even though the organism is recovered by needle aspiration of the node.3,4 Published studies may underestimate the frequency of Group A streptococcus, as these children tend to recover after simple antibiotic therapy and thus not go on to drainage and culture.

BOX 6-1 Infectious Causes of Cervical Adenitis

| Acute Cervical Adenitis S. aureus Group A streptococci Other streptococci, including pneumococci Anaerobic mouth flora, especially after dental work Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)* Cytomegalovirus (CMV)* Adenovirus* Enterovirus* H. influenzae Mycoplasma hominis (newborn) Kawasaki disease |

| Chronic or Subacute Adenitis/Adenopathy Nontuberculous mycobacteria Bartonella henselae (cat scratch disease) Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)* Tularemia Fungi (histoplasmosis, coccidiodomycosis) M. tuberculosis* Toxoplasmosis* Actinomycosis/nocardiosis |

| *Commonly associated with bilateral cervical or generalized adenopathy |

S. aureus is more likely in patients who have had unsuccessful antibiotic therapy and require incision and drainage; in one series of 65 such patients S. aureus was four times more frequently recovered.5 However, as noted earlier, one series found no relation between previous penicillin therapy and recovery of S. aureus on node aspiration.4 Staphylococcal adenitis also may occur in young infants as a result of nursery colonization.6

Other Bacteria

Pneumococci, anaerobic bacteria, or gram-negative rods rarely produce cervical adenitis, especially in young infants.4,6 Neonates may also develop a syndrome called “cellulitis-adenitis syndrome” secondary to Group B streptococci. This condition is more common in males.7 Dental infections may be a predisposing factor for some unusual organisms, particularly anaerobes.8 Haemophilus influenzae is a rare cause of cervical adenitis.

Infectious Mononucleosis

Cervical adenitis in older children and adolescents can be caused by Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). The tenderness is variable depending on the severity of the pharyngitis and often is associated with splenomegaly and generalized adenopathy (Chapter 3). EBV can be associated with a unilateral neck mass.9

Subacute Cervical Adenitis

Nontuberculous Mycobacteria

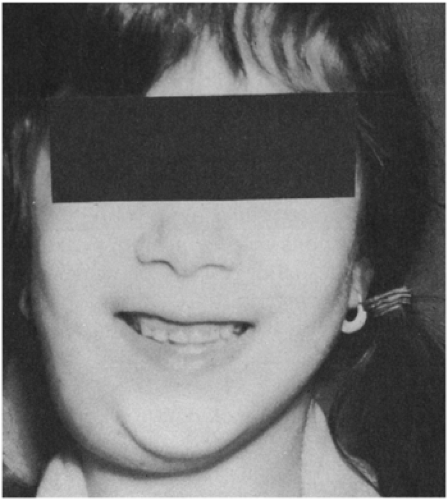

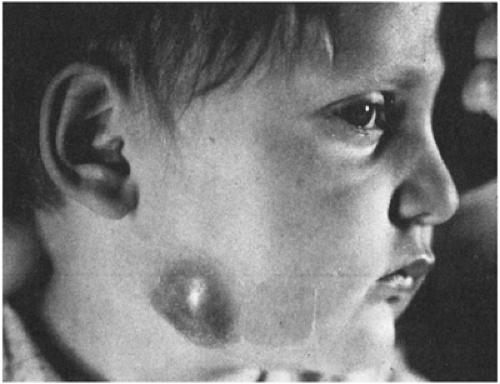

Most of these mycobacteria, previously called unclassified, anonymous, or atypical, have now been assigned species names. Prior to 1978, the most common species recovered from cervical adenitis in children was Mycobacterium scrofulaceum, named for scrofula, an old term for tuberculous cervical adenitis (Fig. 6-2).10,11 An abrupt shift to M. avium intercellulare complex took place in the late 1970s. The reason behind this epidemiologic change is not explained.12

FIGURE 6-2 Chronic cervical adenitis caused by Mycobacterium scrofulaceum. (Photo from Dr. Henry Rikkers) |

Nontuberculous mycobacterial adenitis is a disease that affects predominantly children between the ages of 1 and 5. It is almost always unilateral and has a predilection for the anterior cervical nodes in the submandibular area near the angle of the jaw.12 In two series, there was a slight female predominance.13 Patients are otherwise healthy and present with painless lymph node swelling without significant fever or other systemic symptoms. Signs of local inflammation are scant. Over time, the nodes may develop a violaceous hue, but are usually neither bright red nor hot. Left untreated, many will progress to spontaneous rupture and develop a chronic draining sinus tract; the clinical course is variable, however, and the local progression of any one case is difficult to predict.12 Disseminated disease does not occur in the immunocompetent host.

The histologic appearance of a biopsy specimen of the node depends somewhat on how old the lesion is when it is resected; they tend to progress from dimorphic granulomas to caseating granulomas and finally to calcified granulomas. Acid-fast bacilli can often be found in the smear of aspirated pus or biopsy section. In one large series, 88% of patients had a positive tuberculin skin test (TST) of from 6–15 mm; 9 of 13 “nonresponders” were positive if rechallenged with second-strength (250 TU) purified protein derivative (PPD).12 This TST response, in contrast to that caused by BCG immunization, seems to last for years. In some cases, nontuberculous mycobacterial adenitis that occurred before the age of 5 years has been responsible for making a preemployment TST positive in adulthood.12 Others have found the initial TST response less reliable; Hazra et al. reported that only 2 of 13 patients were TST positive at presentation.13 Skin tests using representative atypical mycobacterial antigens can be compared with the reaction to a standard tuberculin test: in nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases, a larger area of induration is produced by an atypical antigen. Unfortunately, nontuberculous mycobacterial skin-test antigens have been recalled by the FDA because proof of reproducibility was lacking. Culture of a nontuberculous mycobacterium

from a node is conclusive, but in one series, only about one-third of children with the diagnosis based on skin tests had a positive culture.14

from a node is conclusive, but in one series, only about one-third of children with the diagnosis based on skin tests had a positive culture.14

Excisional biopsy of the node is the treatment of choice.14 Whether chemotherapy prevents progression of disease is unknown. Reports of anecdotal success may reflect the natural history of this infection. The use of antimicrobials should be reserved for cases in which surgical excision carries considerable risk, or when surgical excision is incomplete (usually because of proximity of the facial nerve). The combination of clarithromycin (20–30 mg/kg/day) in two divided doses and ethambutol (15 mg/kg/day) as a single dose is a rational choice based on representative sensitivity patterns of atypical mycobacteria.13 If the organism is obtained, therapy can be tailored to susceptibility testing done in a reference laboratory. A prolonged course of therapy may be necessary and should usually be undertaken with the assistance of an infectious diseases specialist.

Tuberculous Adenitis

This is rare in children born in the United States but should be considered in children from other countries or in those with a history of exposure to tuberculosis.15 Mycobacterium tuberculosis is more likely to infect nodes behind the sternocleidomastoid muscle or deep in the neck just above the clavicle.12 In the past, most patients with M. tuberculosis lymphadenitis usually had lung or mediastinal involvement as well, probably because of presentation later in the course of illness. However, a recent series of 60 patients with tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis reported abnormal chest x-ray findings in only 10 (16%).16 In this series, the commonest age group affected was 11 to 20 years, constitutional symptoms were uncommon, and the TST was > 10 mm in 95% and > 15 mm in 84% of patients. Treatment is the same as for pulmonary tuberculosis (see Chapter 8).

Tularemia

Cervical adenitis can be caused by Francisella tularensis, spread by a tick bite or handling of infected tissue carcasses.17,18 The node typically is unresponsive to antistaphylococcal antibiotics and becomes fluctuant and may ulcerate. There is usually a history of an acute illness characterized by fever, headache, abdominal pain, and malaise that antedates the development of the lymphadenopathy. Careful physical examination may reveal a healing ulcer at the site of a tick bite on the scalp or concomitant inflammation of either the conjunctivae or the pharynx. Diagnosis is made by demonstrating an antibody response to Francisella tularensis. Classically, this requires a fourfold or greater increase in antibody titer of paired sera. However, because exposure to F. tularensis is uncommon, a presumptive diagnosis can also be made when a single antibody titer is 1:160 or greater. Antibodies may not be detected until the second or third week of illness. Culture is not recommended because of the risk of laboratory personnel acquiring inhalational disease.

Toxoplasmosis

The relative frequency of toxoplasmosis as a cause of cervical adenitis or adenopathy in the United States is not clearly established.19 Probably, it is frequently undiagnosed because the patient improves and diagnostic studies are not done. In one outbreak, 25 (68%) of 37 patients were ill enough to seek medical attention, but the correct diagnosis was made in only 3 (12%).20 The most common presenting symptoms were fever, lymphadenopathy, headache, and myalgia.

Exposure to cat feces or undercooked meat may signal a need to suspect the diagnosis. Toxoplasmosis should also be considered when atypical lymphocytosis is present with a negative heterophile test. It can be confirmed by demonstrating a fourfold rise in titer of immunoglobulin (IgG) to Toxoplasma antibodies or by the presence of IgM antibodies in a single specimen. However, the quality of available tests is highly variable; false-positive and, to a lesser extent, false-negative results have been a problem with some commercial kits.21

A highly sensitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) that worked well in the diagnosis of both encephalitis and myocarditis due to Toxoplasma gondii failed to identify the organism in 8 of 9 lymph nodes with histologically proven toxoplasma infection.22 The histopathologic findings, however, are highly characteristic and can be identified by experienced pathologists.23 The cyst form of the parasite can sometimes be seen in histologic sections of excised lymph nodes.24

Cat Scratch Disease

The enlarged nodes are in the head and neck in about one-fourth of patients with cat scratch disease (CSD) (Fig. 6-3).25 Cat scratches are found in some

patients; a history of cat exposure is very common. Bacteremia with Bartonella henselae, the agent of CSD, is more common in kittens than in full-grown cats and in cats that spend part of their time outdoors than in those restricted to a home environment. Suppuration occurs in 10–25% of infected nodes.25,26 Despite the fact that this disease was originally called cat scratch fever, systemic symptoms such as fever are relatively uncommon; about one-fourth may have temperature elevation to greater than 38.3°C (101°F), usually for less than a week. A rash, conjunctivitis, or parotid enlargement is noted in 3–5% of patients. The enlarged node is usually noticed about 2 weeks after the scratch but may occur as late as 7 weeks or as early as 3 days.25 In certain locations (such as the southeastern United States), this condition is one of the most common causes of subacute lymphadenopathy in childhood. Cats can also transmit the infection by licking nonintact skin. Surgical removal or biopsy is unnecessary for diagnosis, but is sometimes performed for patient comfort.

patients; a history of cat exposure is very common. Bacteremia with Bartonella henselae, the agent of CSD, is more common in kittens than in full-grown cats and in cats that spend part of their time outdoors than in those restricted to a home environment. Suppuration occurs in 10–25% of infected nodes.25,26 Despite the fact that this disease was originally called cat scratch fever, systemic symptoms such as fever are relatively uncommon; about one-fourth may have temperature elevation to greater than 38.3°C (101°F), usually for less than a week. A rash, conjunctivitis, or parotid enlargement is noted in 3–5% of patients. The enlarged node is usually noticed about 2 weeks after the scratch but may occur as late as 7 weeks or as early as 3 days.25 In certain locations (such as the southeastern United States), this condition is one of the most common causes of subacute lymphadenopathy in childhood. Cats can also transmit the infection by licking nonintact skin. Surgical removal or biopsy is unnecessary for diagnosis, but is sometimes performed for patient comfort.

The diagnosis is usually made serologically, with a single elevated titer of B. henselae IgG or IgM often considered diagnostic, although unfortunately, both false-negative and false-positive results are relatively common.27 In our experience, some children with CSD have negative serology until relatively late in the disease; therefore, if suspicion of CSD is high, serologic titers should be repeated. If the diagnosis remains in doubt, definitive etiologic diagnosis can now be obtained by PCR of aspirated pus.28 A small percentage of patients who appear to have an enlarged node as the sole manifestation of CSD can be demonstrated to have hepatic and splenic microabscesses by abdominal ultrasound.29 This procedure should not, however, be used as a diagnostic test for CSD. The presence of asymptomatic hepatosplenic abscesses does not mandate therapy.

Actinomycosis

“Lumpy jaw” is the most characteristic pattern of actinomycosis in cattle, but it is a very rare disease in humans.30 Usually, there is a firm, tender mass in the submandibular area, which often results in draining sinuses. Drainage from these sinuses may contain characteristic “sulfur granules.”30 The infection spreads locally without regard for potential spaces or fascial planes. Males outnumber females. Rarely, the disease extends to the mandible and produces osteomyelitis. Typically, the center of the mass becomes black and necrotic.

Nocardiosis

Cervicofacial nocardiosis in children can occur without any immune deficiency and typically presents as a pustule and regional submandibular adenopathy, either of which may produce chronic drainage.31 The drainage may contain sulfur granules, mimicking actinomycosis. Nocardia are weakly acid-fast, and Kinyoun stain will sometimes differentiate the two diseases.32

Fungi

Other Causes

Patients with acute HIV infection may present with a monolike illness, which often includes bilateral cervical adenopathy.35 Yersinia enterocolitica is a rare cause of cervical adenitis.36

Lymphogranuloma venereum is also a rare cause of cervical lymphadenitis and is found in individuals with oral-genital contact.37 Syphilis is a rare cause that can be excluded by a VDRL test.

Mycoplasma hominis is a possible cause of cervical adenitis in the newborn perod.38 This infection is probably a result of aspiration of normal flora of the uterine cervix before or during delivery.

Kawasaki Disease

“Mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome” is a synonym for this cause of cervical lymphadenopathy; it is discussed in Chapter 11.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree