Eye, Ear, and Sinus Syndromes

Acute Otitis Media

Otitis media is best considered a disease of eustachian tube dysfunction. The bacteria trapped in the middle ear represent the nasopharyngeal flora. Antibiotic treatment is aided by gradual and spontaneous improvement in eustachian tube function during the natural history of the disease. The physiology and mechanism of eustachian tube dysfunction and the frequency of various pathogens have been well reviewed.1,2

Ear Examination

Cleaning of the Ear Canal

The ear should be examined as thoroughly as possible before attempting to remove the earwax, because such attempts sometimes make adequate removal and visibility more difficult.

Suctioning is the most effective method of removing wax. A bent 14-gauge blunt needle attached by tubing to a trap and a suction machine is popular and is especially useful for sticky wax. Water irrigation is also useful if there is no perforation. It can be done using either an ear syringe or a water-jet machine of the type used for cleaning between teeth. The water-jet machine should be set at its lowest force because perforation can occur at the highest force. Tools such as a dull loop or a dewaxing speculum also can be used. Large cotton swabs are not helpful, but small nasopharyngeal swabs can be. Calcium alginate swabs are very flexible and can be bent into an effective and pliable loop. Wax solvents or hydrogen peroxide followed by water irrigation or suction have been found useful by some physicians. However, severe local reactions to commercial wax solvents have been reported. These reactions can be avoided by rinsing the ear canal with water after allowing the solvent a few minutes to work.

Appearance of the Tympanic Membranes

After the wax has been adequately removed, the tympanic membranes should be carefully examined. The eardrum is normally gray or pink, but can also be red, blue, or injected (prominent blood vessels). Tympanic membranes are often red in a crying infant or in a baby with fever from any cause. Comparing the degree of erythema with the other tympanic membrane may be helpful.

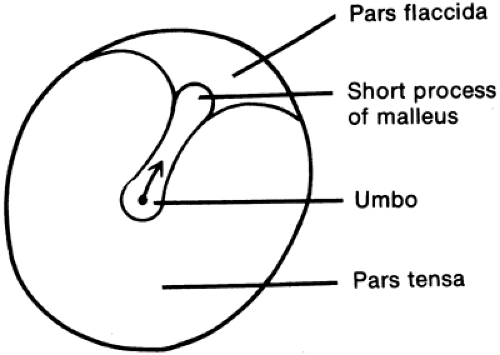

The drum normally appears thin and reflects the otoscope light. Diseased drums can appear dull or thick without light reflection. The drum has a normal position but can be bulging or retracted (atelectatic). Perforations, calcifications, whitish exudate, or bullae may be noted. Landmarks should be noted as an aid to description. The more complete the description, the easier it is to gauge improvement at the time of follow-up examination. A simple diagram of the eardrum can be sketched and labeled for the patient’s record (Fig. 5-1).

Pneumatic Otoscopy

The mobility of the eardrum should be evaluated by applying pressure and suction, usually by means of a rubber bulb attached to the head of the otoscope by a rubber tube. For this technique to be effective, there must be an adequate air seal between the speculum and the ear canal.1 Failure to perform an evaluation of the tympanic membrane’s mobility is one of the most frequent mistakes in pediatric practice. Any examination of the middle ear that

does not include an assessment of mobility is incomplete. Incomplete examination often leads to incorrect diagnosis; in this case, it often leads to overdiagnosis of otitis media, an error that is to be strenuously avoided.

does not include an assessment of mobility is incomplete. Incomplete examination often leads to incorrect diagnosis; in this case, it often leads to overdiagnosis of otitis media, an error that is to be strenuously avoided.

FIGURE 5-1 Diagram of landmarks of right tympanic membrane. Note that a line from the umbo to the short process points to the right, the side being examined. |

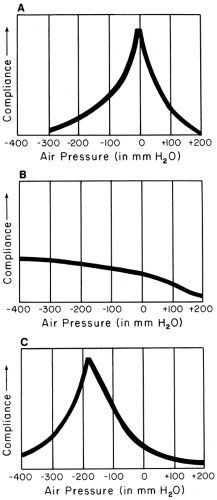

Failure of the eardrum to move with suction and pressure implies that the middle ear is full of fluid or is under negative pressure. A normal eardrum moves in and out easily with gentle pressure changes (Fig. 5-2A). If the drum only moves outward, it may be atelectatic (collapsed), as in the tympanogram shown in Figure 5-2C. Pneumatic otoscopy is a reasonably accurate way of detecting and observing the course of fluid in the middle ear. Rarely, an immobile drum is caused by a rigid or scarred membrane or an undetected perforation.

Tympanometry

In tympanometry, also called impedance audiometry, changes in the reflection of sound energy by the tympanic membrane are measured in the external ear canal in response to changes in ear-canal pressure (Figure 5-2).3 As in pneumatic otoscopy, a pressure seal is required. This method has been especially useful in studying the development of middle-ear effusions and in screening young children for asymptomatic effusions, because large numbers of examinations are needed to make the equipment cost effective. Tympanometry is also being used to investigate the onset, diagnosis, and course of acute otitis media. As a more objective measure of the presence of middle ear fluid, tympanometry is also a good training tool for medical students, residents, physicians assistants, and nurse practitioners; the “student” can examine the middle ear using pneumatic otoscopy first, and then confirm the validity of his/her examination by tympanometry.

Acoustic Reflectometry

Middle-ear effusions can be detected by a simple acoustic otoscope and confirmed by myringotomy or tympanocentesis.4

Tympanocentesis

Since the 1970s, needle puncture of the tympanic membrane (tympanocentesis) has been used sporadically. It can be useful to derive statistical information about the frequency of various bacteria in middle-ear effusions. Tympanocentesis is also used

by some physicians in particular situations, as described later. The technique has been described for both aerobic and anaerobic collection of specimens.5 In 6 (5%) of 122 children with bilateral acute otitis media, culture results revealed different pathogens from the two ears.6 This is unlikely to be clinically significant, as many cases self-resolve without therapy, as discussed later. However, it may explain why on some occasions one side may respond poorly and the other well to treatment.

by some physicians in particular situations, as described later. The technique has been described for both aerobic and anaerobic collection of specimens.5 In 6 (5%) of 122 children with bilateral acute otitis media, culture results revealed different pathogens from the two ears.6 This is unlikely to be clinically significant, as many cases self-resolve without therapy, as discussed later. However, it may explain why on some occasions one side may respond poorly and the other well to treatment.

Criteria for tympanocentesis include: (1) a severely ill child who has developed otitis while receiving an antibiotic or who is still toxic after 48 to 72 hours of antibiotic therapy; (2) otitis in the sick-appearing newborn or in an immunocompromised child; (3) middle-ear effusion in a toxic infant without other signs of infection or in whom there is a suppurative complication without accessible culture material (i.e., brain abscess or cerebral venous sinus thrombosis); or, sometimes, (4) chronic middle-ear effusion with an acute exacerbation. In addition, continued clinical failure after changing antibiotics is a relative indication for tympanocentesis.

Predisposing Factors

Otitis media is generally more common in boys than in girls. Eskimos and Native Americans have a particularly high incidence. Patients with cleft palate, submucous cleft palate, Down syndrome, supine swallowing (bottle-propping), allergic rhinitis, environmental tobacco smoke exposure, or exclusive bottle feeding have a higher incidence of middle-ear infection. Most cases of acute otitis media are preceded by a viral respiratory infection.7 All respiratory viruses can predispose to the development of otitis media.

Classic Clinical Findings

The classic clinical picture of otitis media is the sudden development of fever and otalgia in a patient with a respiratory infection, usually the common cold syndrome. Unfortunately, the classic findings are often absent. Fever is variably present. Small children are not able to complain of ear pain, but may tug at or dig into their ears. Ear tugging in and of itself (i.e., in the complete absence of other signs of disease) is not usually a sign of acute otitis media.8 Young children may have nonspecific signs of illness, such as irritability, decreased appetite, or diarrhea.

Examination of the ear may reveal a red tympanic membrane that is tense or bulging or may show the presence of pus behind the thickened membrane. Insufflation shows decreased movement with both positive and negative pressure. The tympanic membrane may have blisters or bullae on it (bullous myringitis, discussed later). A gray bulging membrane may be found.9 Very high fever (above 40°C) is rare.10 The white blood cell count is of no predictive value.11

Classification

Otitis media can be classified on the basis of a number of variables. The onset and course can be acute, subacute, chronic, asymptomatic, or recurrent. Accurate classification on the basis of middle-ear fluid is possible only if fluid is examined directly; that is, only if there is spontaneous perforation with drainage or if tympanocentesis or myringotomy is performed. The middle-ear fluid may be purulent (cloudy, with many white blood cells), serous (clear and yellow like serum), or mucoid (sticky, with threads of mucus).

Problem-oriented diagnoses are not yet widely used to describe acute otitis media, but they are gaining in popularity. The frequency of antibiotic prescriptions for otitis media has hastened the development of resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae, which has forced pediatricians to come to terms with the concept of problem-oriented diagnosis in otitis media in order to have a conceptual basis for a “watch and wait” approach to certain kinds of otitis media. It is, therefore, helpful to make problem-oriented descriptive diagnoses on the basis of the onset and course of the illness and the appearance and mobility of the tympanic membrane. If middle-ear fluid is obtained for examination, additional diagnostic descriptions can be given. A reasonable classification according to diagnoses that can usually be made is shown in Box 5-1.

The management of a patient with otitis media needs to be based on the specific subgroup diagnosis. The following are some examples of this approach:

Fever with red, but mobile drums. This category, sometimes loosely called “red ear,” is probably the most frequent form of so-called acute otitis media reported in series published before 1970. However, those who believe that middle-ear fluid is required for the diagnosis do not regard red but mobile tympanic membranes as otitis media. This is probably the most reasonable position,

because tympanic membranes can become transiently red with crying or fever. Most young children who are brought to the doctor’s office and have a speculum placed into their external ear canal have both fever and crying. Inclusion of many febrile children with “red ears” in early studies of otitis media probably decreased the accuracy of these studies and led to some reports that a placebo was as effective as an antibiotic. The frequency of development of middle-ear fluid in these patients has not been adequately studied, but it is reasonable to suspect that large series that concluded antibiotics were no more effective than placebo probably included many such patients.

Acute otitis media (AOM). This diagnostic category corresponds to what has been called acute purulent otitis media. This is a disease with a sudden onset, ear pain, and usually some degree of fever. Patients are clearly suffering from a moderate to severe illness. The eardrum is usually red, the normal landmarks are obscured, and there is fluid behind the drum that can be appreciated visually or by poor mobility on insufflation. The exact consistency of fluid seen behind the inflamed tympanic membrane in this condition is not always easy to determine; it may be assumed that pus is there based on the presentation and course of this illness. This is the classification of otitis media that usually calls for antimicrobial therapy, as discussed later.

Otitis media with effusion (OME). This is the current classification of a disease that used to be more frequently referred to as “serous otitis media.” OME is a condition in which the patient has fluid behind the tympanic membrane, but has neither signs nor symptoms of acute illness. The patient may have some dullness or even some redness to the drum. Otalgia, if present at all, is mild. Older patients may complain of decreased hearing acuity or may say that they feel as if they should but cannot “pop their ears.” OME may follow a course of AOM, or it may arise by itself. Some patients have bacteria recovered on tympanocentesis, but most do not. Many of these effusions will resolve spontaneously over the course of 1 to 3 months.

Bullous myringitis. This condition is characterized by the formation of blebs, vesicles, or bullae on the tympanic membrane, sometimes creating a cobblestone appearance. It tends to be quite painful, although some children do not seem to be bothered by it. It was originally linked to mycoplasmal infection, but has subsequently been shown to be simply a variant of AOM, as discussed later.

Recurrent otitis media. This is defined by recurrences of AOM with normal tympanic membranes between acute episodes.

Draining ear. This is a preliminary diagnosis that should eventually be resolved into either acute otitis externa, AOM with perforation, or chronic otitis media with perforation.

Chronic middle-ear effusion. If the effusion persists for more than 3 months, as it does in 5–10% of acute cases, it is defined as chronic. Myringotomy with aspiration is often the first step in surgical treatment. If the effusion reaccumulates, ventilation tubes may be necessary, as described later in this chapter. In general, the longer the middle-ear fluid is present, the more viscous it becomes, and thus the more difficult it is for it to drain spontaneously.

Asymptomatic middle-ear effusion of unknown duration. This problem-oriented diagnosis can be made when immobile, dull eardrums are noted on a routine examination. A good air seal is needed for the test. This condition is also called asymptomatic OME, although this term assumes that the fluid is serous rather than purulent or mucoid. Asymptomatic effusion can be a stage in the course of AOM. This particular condition should never prompt a course of antibiotics.

Draining ear in a child with tympanostomy tubes. It is appropriate to consider this as a separate category because the management is different from that of the child without tympanostomy tubes. As in a child without tympanostomy tubes, this should be classified as either acute or chronic drainage.

BOX 5-1 Problem-orinted Classification of Otitis Media

| Fever and red, mobile drums Acute otitis media Otitis media with effusion Bullous myringitis Recurrent otitis media Draining ear Acute otitis media with perforation versus otitis externa Chronic otitis media without perforation Chronic otitis media with perforation Acute otitis media in a child with tympanostomy tubes Chronically draining ear in a child with tympanostomy tubes Asymptomatic middle-ear effusion |

Possible Infectious Causes

Bacteria

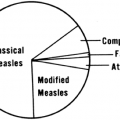

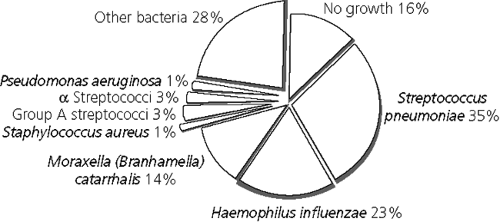

In children with otitis media, the most frequent bacteria recovered from ear puncture are S. pneumoniae (pneumococcus), nontypable Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. The frequency of the various organisms recovered by needle puncture or myringotomy is diagrammed in Figure 5-3.

Approximately 30% of middle-ear cultures show no growth. This sometimes is the result of a failure of the culture techniques to detect fastidious bacteria, small numbers of bacteria, bacteria no longer capable of replication because of antibiotic therapy, or microorganisms other than bacteria. Sometimes the patient’s bacterial infection has been eradicated, although signs and symptoms of inflammation are still present. In other words, you may have cured the patient, but the patient may not know that he has been cured. It used to be thought that anaerobic bacteria accounted for much of this “no-growth” percentage,12 but this is no longer believed to be the case. Aerobic pathogens can be found in middle-ear fluid by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in a high percentage of “sterile” effusions.13 It is still not clear whether this means these patients will benefit from antibiotic therapy. The 30% figure also suggests that in some cases, middle-ear fluid is sterile and not formed as a response to bacterial infection. It supports the concepts that (1) eustachian tube dysfunction is the basic mechanism of otitis media, and (2) not all cases of otitis media require therapy.

FIGURE 5-3 Frequency of various microorganisms found by tympanocentesis in 2807 cases of acute otitis media. (Adapted from Bluestone CD, et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1992;11:S7–S11) |

Gram-negative enteric bacteria and S. aureus were the bacteria most frequently recovered from the middle ear of premature or term neonates in some early studies and may have represented the nasopharyngeal flora of these infants,14 as subsequent studies have indicated that these bacteria are uncommon in infections. Young infants occasionally have Group B streptococci recovered from the middle ear.15 The recovery of Neisseria species or of S. epidermidis, which are not usually associated with disease, also suggests that some bacteria recovered from the middle ear are, in fact, normal flora of the nasopharynx that have reached the middle ear after eustachian tube dysfunction and are not the cause of the otitis media. In addition, inadequate disinfection of the ear canal before tympanocentesis may be a factor, as S. epidermidis and diphtheroids are especially likely contaminants from the external ear canal.16 The possible contribution of these low-virulence organisms to the illness has not been adequately evaluated; they may be important in some cases. If a young infant (less than 2 months of age) has otitis media and appears toxic, hospitalization, tympanocentesis, lumbar puncture, blood culture, and intravenous antibiotics are indicated. AOM with low-grade fever in a well-appearing young infant can usually be treated with oral antibiotics provided that close follow-up can be ensured.

Viruses

It has now been well established that viruses can not only predispose to otitis media because of inflammation of the eustachian tubes, but they can also be etiologic agents of otitis media.17,18 Respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza viruses, coxsackie

viruses, and others have been recovered from middle-ear fluid by conventional cell culture.19 Studies suggest that the concomitant presence of a viral pathogen and a bacterial pathogen in the middle-ear space signals a disease process that is more difficult to eradicate.20 On occasion, a virus is the only pathogen recovered. Viral antigens and genetic material have also been found by ELISA and PCR. PCR positivity for viral antigens does not prove active infection, as dead or replication-incompetent viruses will still produce a positive PCR.

viruses, and others have been recovered from middle-ear fluid by conventional cell culture.19 Studies suggest that the concomitant presence of a viral pathogen and a bacterial pathogen in the middle-ear space signals a disease process that is more difficult to eradicate.20 On occasion, a virus is the only pathogen recovered. Viral antigens and genetic material have also been found by ELISA and PCR. PCR positivity for viral antigens does not prove active infection, as dead or replication-incompetent viruses will still produce a positive PCR.

Any respiratory viral infection can serve as an inciting event for the development of AOM. It is often thought that RSV is the agent most likely to do so;21 however, the most comprehensive study on this issue to date shows that the difference in the prevalence of otitis media in children with culture-proven respiratory syncytial virus infection versus the prevalence in infection with other respiratory viruses is small.22

Mycoplasma

Bullous myringitis occurs in some cases of experimental infection of human volunteers with Mycoplasma pneumoniae.23 However, later studies emphasize the fact that Mycoplasma is a rare cause of otitis media, even in the presence of bullous myringitis.24 In fact, when tympanocenteses are performed in patients with bullous myringitis, the breakdown of pathogens mirrors that in patients with AOM in the absence of bullae (i.e., S. pneumoniae is most common, followed by nontypable H. influenzae, and then by M. catarrhalis).24 These findings suggest bullous myringitis is, in fact, nothing more than a variant of AOM. As such, it should be treated with the same antibiotics one would choose for uncomplicated AOM. The clinician should feel absolutely no compulsion to add erythromycin or to use an erythromycin-containing antibiotic or a newer macrolide in the treatment of patients with bullous myringitis.

Chlamydia

Chlamydia trachomatis appears to be a cause of some recurrent middle-ear effusions, as discussed later. Special culture techniques and PCR revealed the presence of C. pneumoniae in a small percentage of both acute and refractory cases of otitis media. In most cases it was not the sole pathogen recovered.25

Noninfectious Etiologies

Hemorrhagic or bullous myringitis can result from trauma.

Treatment

Many cooperative studies of antibiotics have been done, and excellent reviews are available.26,27 It is important to distinguish the subgroup of otitis media to which a particular management applies.

No Antibiotic Treatment

Physicians in some European countries have adopted a strategy of watchful waiting (or as one author phrased it, “masterful inactivity”28) for most cases of AOM. Analgesics are given. Several published studies show a remarkable success rate using this strategy.28,29 Physicians in the United States have been reluctant to adopt this concept because of concerns about mastoiditis, persistent effusions, spontaneous perforation, and other complications.26,27 However, the rapid emergence of penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae in most areas of the United States has necessitated a rethinking of our routine antibiotic approach to the care of patients with otitis media. In the late 1980s, papers that urged pediatricians to withhold therapy for a subset of children with otitis media began to emerge.30,31 It has been well recognized for years that a high percentage of cases labeled “otitis media” will resolve without antibiotic therapy.

Recent recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics have emphasized a selective approach to the treatment of otitis media.32 Patients with OME (mild redness of the tympanic membrane, low-grade to no fever, a serous fluid collection behind the drum, and no toxicity) are best observed without antibiotic therapy. Analgesia, preferably with acetaminophen with or without topical analgesics, may be prescribed if needed. Patients with “red ear” should never be administered antibiotic therapy.

Acute Otitis Media

Patients with true AOM (i.e., bright red, bulging tympanic membranes; moderate to high fever; severe otalgia; or toxicity) are clear candidates for antibiotic therapy. Therapy should be directed at the pathogens most likely to require therapy (see next paragraph).

Virgil Howie’s early studies of the bacterial etiology of otitis media using placebo therapy and serial tympanocenteses reveal that the spontaneous resolution rate of otitis media is, to a large extent, determined by the specific pathogen.33 His data show that of 25 children who had “nonpathogens” (most of which were probably M. catarrhalis) at the time of the first tympanocentesis, 7 (28%) had no exudate at 2- to 7-day follow-up. Thirteen (52%) of the 25 had a persistently positive culture. H. influenzae was somewhat less likely to spontaneously resolve: of 21 initial isolates, 3 (14%) had no exudate and 12 (57%) remained culture positive by the repeat tympanocentesis. In contrast, of 45 children with isolates of S. pneumoniae, only 2 (4%) had no exudate, and 36 (82%) were still culture positive at follow-up tympanocentesis.33 Persistence of viable bacteria after failed treatment also varies by pathogen, being highest in S. pneumoniae infections.34 In this study, only 5% of cultures of AOM treatment failures yielded M. catarrhalis, despite the fact that almost 90% of the M. catarrhalis isolates were beta-lactamase producers.34 Experience and subsequent clinical research have proved this fact: AOM caused by S. pneumoniae is the least likely to resolve on its own. Group A streptococcal otitis also has a low spontaneous resolution rate. If there were a way of knowing which pathogen the patient was harboring, antibiotic therapy could almost certainly be safely withheld for most patients with H. influenzae and almost all patients with M. catarrhalis ear infections. The fact that suppurative complications of otitis media such as mastoiditis are almost never caused by M. catarrhalis further underscores the low pathogenic potential of this organism in otitis media.

It is difficult to establish the exact etiologic agent in any one case of AOM; nasopharyngeal cultures do not reflect the pathogen infecting the middle-ear space and are therefore not recommended. Because there is no way, short of obtaining middle-ear fluid for culture, of knowing with certainty what pathogen is inhabiting the middle ear of a patient, and because suppurative complications are potentially devastating, antibiotic therapy against AOM should, first and foremost, be directed against the pneumococcus. In doing this, some activity against beta-lactamase-producing H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis will be lost, but the trade-off is reasonable, given the fact that most patients with these other pathogens will undergo spontaneous resolution of their disease, even if they have true AOM at the onset. Studies of inflammatory mediators in serum have shown that the body’s response to the pneumococcus differs markedly from its response to other pathogens of otitis media.35 These serologic findings have a clinical correlate: patients with pneumococcal otitis media are, in general, sicker than those with AOM due to H. influenzae or M. catarrhalis. Specifically, children with S. pneumoniae AOM are more likely to have a temperature of greater than 38.5°C and to have red and bulging tympanic membranes.36,36a The difference is more pronounced in children less than 24 months of age, in whom the findings of fever and a red, bulging tympanic membrane have a sensitivity of almost 60%, and absence of these findings has a specificity of 98% for otitis media caused by S. pneumoniae. Pneumococcal otitis media, therefore, can almost be looked on as a separate disease from otitis caused by other bacteria. One editorial suggested that physicians should think only about pneumococcus when planning therapy for AOM.37

Amoxicillin is still the best drug for initial treatment of AOM, despite increasing penicillin resistance in S. pneumoniae isolates, mainly because of its excellent penetration into the middle-ear space and its slow elimination.38,39 “Resistance” is not absolute, but is related to the concentration of drug needed to inhibit the growth of a bacterial isolate (MIC). Once the MIC is exceeded, bacterial killing will take place. The rationale behind high-dose amoxicillin therapy is to achieve middle-ear fluid levels that exceed the MIC of the organism. If there is a high prevalence (greater than about 25%) of penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae in your area, it is prudent to begin therapy with an amoxicillin dose of approximately 80–90 mg/kg/day, as opposed to the more traditional dosing of 40–45 mg/kg/day. In areas of low prevalence, low- or intermediate-dose amoxicillin can be started, with a follow-up visit in 48–72 hours. Early studies showed that lack of clinical improvement in the first 2–3 days predicted clinical failure of the antibiotic regimen; later studies correlated the clinical response with early eradication of the infecting organisms.40 Changing therapy early in the course of disease is preferable to treating with an ineffective antibiotic for a full 10 days. The most commonly used second-line agent is amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. A new formulation of this antibiotic that contains these agents in a 14:1 ratio and allows for a high-dose regimen without excessive rates of diarrhea has improved tolerability. A child with no improvement after consecutive 3-day courses of two different antibiotics should

probably undergo tympanocentesis. This has the benefit of draining the pus, which may be therapeutic, in addition to enabling a sample to be obtained for culture and sensitivity testing.

probably undergo tympanocentesis. This has the benefit of draining the pus, which may be therapeutic, in addition to enabling a sample to be obtained for culture and sensitivity testing.

A patient with unilateral AOM and ipsilateral conjunctivitis has otitis-conjunctivitis syndrome. Patients with this syndrome are more likely to have H. influenzae as the causative agent of their AOM. Because of the high likelihood of beta-lactamase production by H. influenzae isolates, patients with otitis-conjunctivitis syndrome should be treated with a drug that is beta-lactamase stable. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (FMP-SMX), amoxicillin-clavulanate, a second- or third-generation cephalosporin, or a macrolide would be appropriate. Cost concerns favor a trial of TMP-SMX. No systematic comparison of these alternatives in this situation has been performed.

Several acceptable alternative initial therapies are available for penicillin-allergic patients. Cefpodoxime, cefuroxime, and cefprozil have been tested and found to be reasonably effective in the treatment of AOM. Cefdinir is a similar drug that has the advantage of being more palatable. Caution must be used when prescribing cephalosporins to patients with true penicillin allergy, as there is a small (<5%) incidence of cross-sensitivity. Cefaclor suspension should not be used. This antibiotic is unstable in suspension; one of the breakdown products causes a rash to occur in some patients. Developing a rash while taking cefaclor suspension, therefore, does not prove cephalosporin allergy. In any case, cefaclor is a poor choice as empiric therapy for AOM because its activity against S. pneumoniae is unacceptably low. Loracarbef, ceftibuten, and cefixime also have relatively poor activity against S. pneumoniae. Clindamycin has activity against most strains of the pneumococcus, but no activity against H. influenzae or M. catarrhalis, and its use should probably be reserved for cases in which S. pneumoniae has been cultured from middle ear fluid. The combination of erythromycin ethylsuccinate and sulfisoxazole suffers from the fact that these two drugs are antagonistic. The newer macrolides (azithromycin and clarithromycin) are popular but offer no particular advantage over other agents. Pneumococcal resistance against these agents appears to be on the rise.

Persistent middle ear effusion

Effusion is still present in about 50% of children 10 days after treatment,41 especially those younger than 24 months.42 With time, the effusion resolves: 90% are resolved within 3 months. After that time, few cases resolve.43

It used to be common practice to have a 2-week follow-up visit for all children with AOM. Because the natural history of the disease is that at least half of the children will not have a normal ear examination at that visit, it is prudent to delay the follow-up visit to approximately 4 weeks in children whose symptoms have resolved. As mentioned earlier, children who still have ongoing moderate to severe symptoms should be seen sooner than 2 weeks, preferably at 2 to 3 days. Children with continued effusion, but without symptoms at 4-week follow-up are best managed by watchful waiting and follow-up evaluation. TMP-SMX for 14 days failed to promote resolution of effusion in a controlled study.41

Persistence of middle-ear fluid after acute otitis media occurs more commonly in white children under 2 years of age and can cause transiently impaired hearing, although long-term follow-up reveals normal hearing and normal speech and language development in most.44 When an episode of AOM results in persistence of middle ear fluid for 3 months, as described in the preceding section, and the tympanic membrane remains immobile, consultation with an ear specialist is advisable. A short course of oral steroids in concert with antimicrobial therapy has been advocated as a last resort before referral to an otolaryngologist,45 but not all studies have shown a beneficial effect.46 Recent guidelines recommend against their use.46a

Bullous myringitis

As discussed previously, this condition should be considered a variant of AOM, and treated appropriately. If there are associated middle or lower respiratory findings, it may be reasonable to consider therapy with a macrolide, although data about the efficacy of this approach are lacking.

Asymptomatic effusion

OME can be asymptomatic in early infancy and may be detected only by routine examination at well-child visits.47 Fifty percent of effusions in young infants resolve in one month, but about 15% will remain unresolved after 3 months. Therapy of this primarily benign condition with TMP-SMX for 4 weeks significantly increases the frequency of resolution compared with placebo, but the therapy itself is not benign. A 2-week course of amoxicillin also

hastens resolution. In the era of antimicrobial resistance, an approach of no antibiotic therapy and monthly follow-up seems wise, especially in the absence of risk factors for severe or disseminated infection (extreme young age, prematurity, or immunodeficiency states). Antihistamine-decongestant combinations offer no additional benefit.48

hastens resolution. In the era of antimicrobial resistance, an approach of no antibiotic therapy and monthly follow-up seems wise, especially in the absence of risk factors for severe or disseminated infection (extreme young age, prematurity, or immunodeficiency states). Antihistamine-decongestant combinations offer no additional benefit.48

Neonatal otitis media

Examination of the ear in the newborn requires relatively deeper penetration with the speculum and pulling of the pinna down and posteriorly in order to straighten the canal.49 In the first 3 months of life, hospitalized infants, especially those in intensive care units, may have S. aureus or enteric gram-negative bacilli recovered on tympanocentesis,50 whereas infants this age seen as outpatients are likely to have the conventional pathogens.51

It has been suggested that amniotic fluid viscosity is a relevant variable in resorption of middle-ear fluid in the first 48 hours of life and may be relevant to the pathogenesis of later middle-ear effusions and infections in young infants.52 The eustachian tube is more horizontal, and the tensor veli palatini muscle, the contraction of which opens the tube, does not have mature function in the young infant. In fact, innervation and function of this muscle usually is not complete until about the age of 6 years. This helps to explain why recurrent otitis media becomes a relatively rare disease in children over the age of 6.

Other Treatment

Oral decongestants and antihistamines were of no value for AOM or for chronic effusion in two controlled studies.21,48 In the third study, antihistamines for AOM were associated with a longer duration of middle ear effusion.52a In many children, antihistamines produce sedation, masking the neurologic symptoms of rare complications such as meningitis or brain abscess. However, antihistamines may be helpful in recurrent OME in children with documented allergic problems. The use of nonsedating antihistamines in children with this condition has not been evaluated.

Allergies and upper respiratory infections appear to disrupt eustachian tube function. Prevention of otitis media by symptomatic treatment of allergies has not been demonstrated. The incidence of AOM are decreased in children given influenza vaccination53 and also in children who were treated with respiratory syncytial virus-enriched IVIG for the prevention of RSV disease.54

Myringotomy

Incision of the tympanic membrane may be useful for relief of pain but does not appear to significantly alter the clinical course or prognosis of the illness.22 It rarely has been used in the treatment of AOM since the 1970s and usually need not be considered unless medical therapy fails. Myringotomy should only be performed by physicians experienced with the procedure. In selected cases, tympanocentesis can be done to relieve pressure. More frequently, tympanocentesis is performed to obtain fluid for culture in refractory cases. The recovery and speciation of pathogens is very helpful because antibiotic susceptibility testing can be performed and the results used to guide antimicrobial decisions.

Some physicians are now using a laser device to puncture the tympanic membrane, principally for relief of pressure, in cases of severe or refractory AOM. The true utility of the procedure awaits further study; it shows some potential in reducing the unnecessary use of antibiotic therapy.

Analgesics

Acetaminophen or ibuprofen may be used for relief of ear pain. On rare occasions, a dose or two of codeine may be indicated for severe pain. Topical application of Auralgan, containing dehydrated glycerin, antipyrine, and benzocaine, may be of some value in pain relief and may soften earwax for easier removal. This preparation is especially useful in the first two or three days of therapy for a full-blown case of AOM, in which pain can be intense.

Duration of Therapy and Follow-Up

Reexamination, as mentioned earlier, should be done in 48–72 hours in severe or unresponsive cases. It can be postponed to 4 weeks for others. Older children (greater than age 3 or 4) may not require a formal follow-up examination at all: if the child says he is feeling better, the condition is almost always resolved. Keep in mind that even at a 4-week follow-up visit, some fluid may still be present, although it may be sterile.

The optimal duration of therapy has undergone some intensive investigation over the past few years.55 Antibiotics with long half-lives, such as azithromycin, have been recommended to be given for only 5 days. This recommendation is based on the fact that a 5-day course provides almost 10 days of antimicrobial coverage given the disappearance

of the active drug from the tissues. More recently, recommendations have been published that children at low risk for suppurative complications, (such as children greater than 4 years old, children without a history of frequent or severe AOM, and children without severe disease at the time of diagnosis) can be treated for 5–7 days with conventional antibiotics.32 Children less than 5 years old, those with frequent AOM or a history of severe AOM or AOM with complications, and patients with high fever or who are ill appearing at the time of diagnosis should continue to receive a full 10-day course of antibiotic therapy.

of the active drug from the tissues. More recently, recommendations have been published that children at low risk for suppurative complications, (such as children greater than 4 years old, children without a history of frequent or severe AOM, and children without severe disease at the time of diagnosis) can be treated for 5–7 days with conventional antibiotics.32 Children less than 5 years old, those with frequent AOM or a history of severe AOM or AOM with complications, and patients with high fever or who are ill appearing at the time of diagnosis should continue to receive a full 10-day course of antibiotic therapy.

Studies have shown that one intramuscular injection of ceftriaxone is as effective as a 10-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanate for the initial treatment of AOM.56 For treatment of previously unresponsive cases, three consecutive days of therapy is superior to a single injection.57 However, the use of ceftriaxone for treatment of otitis media should not be routine. A single dose of intramuscular ceftriaxone has been shown to increase penicillin resistance among the pneumococci colonizing the nasopharynx.58 Although some refractory cases of AOM due to multiply resistant organisms will respond to a 3-consecutive-day schedule of intramuscular ceftriaxone,32 this approach to therapy is painful and inconvenient. Sometimes it can allow a patient to avoid ear surgery, and in those cases it seems to be the lesser of two evils.

Draining Ears

A new discharge from the external ear canal can be caused by perforated AOM or acute otitis externa. Ear drainage is an expected finding in the child with tympanostomy tubes and AOM. A chronically draining ear can be caused by chronic otitis media with perforation, with the draining pus producing secondary otitis externa. A chronically draining ear is seldom attributable to otitis externa alone. Chronic drainage may also be a sign of mastoiditis.

Otitis Externa

Acute Otitis Externa

Otitis externa is defined as redness, itching, or edema of the external ear canal, with or without exudate. The ear canal is usually very painful, the pain perhaps aggravated by chewing. Typically, pain is produced by moving the pinna and by insertion of the speculum into the external ear. Fever is uncommon. There may be erythema and edema around the external auditory canal, so that the physician may at first suspect mastoiditis or parotitis. “Swimmer’s ear” is an otitis externa apparently initiated or exacerbated by water in the ear.

Chronic Otitis Externa

This condition is usually secondary to chronic drainage from a perforated eardrum.

Malignant otitis externa

Occurring predominately in adults, especially diabetics, malignant otitis has been observed rarely in newborn infants, and in children with diabetes mellitus or other immunocompromising conditions.59,60 It is characterized by progressive, invasive external-ear infection, typically caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. It is likely that the child will be in poor general health. The disease may invade the bone of the mastoid, mandible, or skull, with cranial nerve paralysis or even death.61 Technetium bone scan may be helpful in the early diagnosis of osteomyelitis associated with malignant otitis externa.61 A 4-week course of parenteral antibiotics active against Pseudomonas has been advised, with surgical drainage only if no clinical response is obtained with antibiotics.62 Both an aminoglycoside and an antipseudomonal penicillin should be used, at least for the first week. Patients who get through this illness may be beset with late complications including sensorineural hearing loss,63 stenosis of the external canal, or necrosis of the tympanic membrane.64

Mechanisms

Otitis externa is usually related to water in the ear canal. This may be caused by excessive exposure to water, such as in swimming (especially under water) or heated whirlpool baths, or by a contaminated infant bath sponge or failure to dry the ear after exposure to water. The external ear canal protects itself with a layer of cerumen, which normally removes contaminants by trapping and moving them slowly toward the outlet of the canal, where they can be removed by gentle swabbing. Anything that damages this layer can predispose to external otitis, including excessive or vigorous cerumen removal with a cotton-tipped swab. Parents should be instructed that it is neither necessary nor advisable to put cotton-tipped swabs into the external ear

canal. Problems of earwax build-up in the external canal are also sometimes related to attempts at wax removal. Inexperienced people may actually be pushing the earwax closer to the tympanic membrane, where it can collect. Once the wax dries, it is harder for it to move toward the outlet as it should. This can also macerate the epithelium of the canal and predispose to otitis externa.

canal. Problems of earwax build-up in the external canal are also sometimes related to attempts at wax removal. Inexperienced people may actually be pushing the earwax closer to the tympanic membrane, where it can collect. Once the wax dries, it is harder for it to move toward the outlet as it should. This can also macerate the epithelium of the canal and predispose to otitis externa.

Otitis externa is more common in the summer. This is presumably because more people are swimming in the summertime; however, some experts believe that excessive humidity of the hot summer air may be a cause, as well.

Etiologies

The principal differential diagnostic problem in a draining ear is distinguishing otitis externa from otitis media with perforation and drainage obscuring the eardrum. The problem is complicated by the fact that a chronically draining ear secondary to otitis media may predispose to subsequent otitis externa. A history of recent swimming or of past otitis media is helpful. Physical examination including manipulation of the canal is also helpful. Patients with rupture of the tympanic membrane (TM) from otitis media will often have a history of severe ear pain with rather sudden resolution, as rupture of the TM often brings relief of pressure pain. They may also have had fever prior to the rupture of the TM. In contrast, patients with otitis externa usually have increasing symptomatology, without a history of relief. Fever is uncommon. Movement of the tragus is sharply painful.

Suctioning of the drainage may allow the clinician to see the perforation of the TM. Perforations may also alter the results of tympanometry, as it measures the volume of air communicating with the external auditory canal.

P. aeruginosa is the organism most often recovered in acute otitis externa, whereas S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, or beta-hemolytic streptococci are more common in AOM with rupture. In addition to Pseudomonas, Proteus species, Escherichia coli, or anaerobes may be recovered from a chronically draining ear. Candida, Aspergillus, or other fungi can cause otitis externa, especially in hot, damp climates.62

Allergic otitis externa is not unusual and may result from eardrops or chronic eczematoid otitis externa. Other diseases, such as Langerhans cell histiocytosis and Wegener’s granulomatosis, are rare causes of draining ears.

Laboratory Approach

Gram Stain

In a chronically draining ear, a Gram stain may reveal more than one kind of gram-negative rod. If only one grows out in culture, the other may be an anaerobe.

Culture

Patients with external ear drainage secondary to otitis externa need not have cultures performed. Patients with chronic otitis media with drainage through a perforated TM or myringotomy tube should have cultures done on the pus. Swabbing pus that is already present in the canal usually yields a mixture of aerobes and anaerobes, most of which are commensals and do not provide any useful information. If the area can be cleaned first, fresh pus is occasionally recoverable. An ENT specialist is able to suction pus from the PE tube orifice or from a perforation, and thus get a more useful specimen. If a culture is obtained within 24 to 48 hours in perforated otitis media, it may provide useful information even without disinfection of the ear canal.65 This is a practical office procedure for any office set up to do throat cultures for beta-hemolytic streptococci, although H. influenzae will not be recovered unless the swab is smeared on a chocolate agar plate and incubated in a candle jar.

Often, the culture shows no growth or yields only a skin contaminant. However, if pneumococci, H. influenzae, or beta-hemolytic streptococci are recovered, the culture is useful and indicates drainage from a recently perforated otitis media. Recovery of P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, or an enteric gram-negative rod suggests exudate from otitis externa or a chronically infected, perforated otitis media. Pseudomonads, however, are frequently commensal; their recovery must be interpreted in clinical context.

Treatment of Otitis Externa

Antibacterial Eardrops

Dilute (0.25%) acetic acid can be effective against P. aeruginosa and is inexpensive. A 1:1 mixture of household vinegar (dilute acetic acid) and rubbing (isopropyl) alcohol adds the drying effect of alcohol

and may also be used. Cortisporin (polymixin B-bacitracin-neomycin-hydrocortisone) suspension can be used without much irritation of the middle ear if the drainage is from a perforation. The clear Cortisporin solution has a theoretical advantage of allowing the canal to be better visualized, but is more acidic than the suspension and often is poorly tolerated because of burning or stinging.62 Ophthalmic solutions of Cortisporin or gentamicin may be tried even if Cortisporin suspension is not tolerated.62 Hydrocortisone-acetic acid (VoSoL-HC) appeared to be as effective as Cortisporin solution in the treatment of otitis externa.66 Otic Domeboro solution (2% acetic acid in modified Burrow’s solution) is another effective local agent that is applied every 3 or 4 hours. It will relieve pain and reduce edema. Umbilical tape or commercially available ear wicks can be used if there is edema of the canal. If the edema is marked, topical agents are unlikely to reach their intended sites. In this situation, referral to an ENT specialist for daily suctioning of debris and wick placement is often necessary.

and may also be used. Cortisporin (polymixin B-bacitracin-neomycin-hydrocortisone) suspension can be used without much irritation of the middle ear if the drainage is from a perforation. The clear Cortisporin solution has a theoretical advantage of allowing the canal to be better visualized, but is more acidic than the suspension and often is poorly tolerated because of burning or stinging.62 Ophthalmic solutions of Cortisporin or gentamicin may be tried even if Cortisporin suspension is not tolerated.62 Hydrocortisone-acetic acid (VoSoL-HC) appeared to be as effective as Cortisporin solution in the treatment of otitis externa.66 Otic Domeboro solution (2% acetic acid in modified Burrow’s solution) is another effective local agent that is applied every 3 or 4 hours. It will relieve pain and reduce edema. Umbilical tape or commercially available ear wicks can be used if there is edema of the canal. If the edema is marked, topical agents are unlikely to reach their intended sites. In this situation, referral to an ENT specialist for daily suctioning of debris and wick placement is often necessary.

Prophylactic use of an antifungal, antibacterial medication (VoSoL) appeared to prevent swimmer’s ear in a controlled study of campers.67 Otic Domeboro left in for 5 minutes is also effective when given on arising, after swimming, and at bedtime.62 A hair dryer may be helpful, but the use of cotton swabs to dry the ear is not recommended,62 as trauma to the canal facilitates the development of otitis externa (OE). Ear hoods are of no value.

Analgesia

Dry heat may be helpful for pain. A few doses of acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or even codeine may sometimes be necessary.

Chronic and Recurrent Otitis Media

Definitions

Recurrent otitis media

Recurrent AOM has been defined as more than three episodes of AOM within 6 months.68 The middle ear is normal, without effusions, between episodes.

Chronic otitis media

Called chronic serous otitis in the past, this pattern is usually defined as a middle-ear effusion that has been present for at least 3 months.68 Persistent structural changes, such as a persistent eardrum perforation, imply past otitis but not necessarily chronic infection. Management of these problems remains difficult for most physicians, and only an introductory discussion of the principles will be given. Some sort of eustachian tube dysfunction is the principal predisposing factor.

Chronic Draining Ear

The diagnosis of chronic draining ear can be made on the basis of a reliable history. Typically, there is a chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) with a perforation. Perforations that occur at the margin are a special problem, because they are often associated with cholesteatomas, discussed later in this section. Chronic draining ear may also be a sign of mastoiditis. CSOM in the child with tympanostomy tubes is a particularly common problem, occurring in 5% to 10% of tube insertions.69

Recurrent Draining Ear

Recurrent draining ear should be the working diagnosis when an ear discharge is present intermittently. The diagnosis of otitis externa can be made if a perforation can be excluded, as discussed earlier in the chapter.

Persistent Middle-Ear Effusion

When an episode of otitis media results in persistence of middle-ear fluid for 3 months, as described in the preceding section, and the tympanic membrane remains immobile, consultation with an ear specialist is advisable.70,71 Persistence of middle-ear fluid after AOM is more common in white children under age 2.72

Terms that imply knowledge about the character of the middle-ear fluid (such as serous otitis) or the mechanism of pathogenesis (such as secretory otitis) should be reserved for cases in which the physician is certain they are correct. Otherwise, the term otitis media with effusion (OME) should be used.

Rarely, the drum appears purple or blue as a result of bloody fluid.73 Trauma can also cause this clinical picture.

Bone conduction (sound heard through the mastoid) is better than air conduction (sound heard through the external auditory canal). Sound from a tuning fork placed on the top of the skull is

lateralized to the ear with the greater impairment of hearing.

lateralized to the ear with the greater impairment of hearing.

If the ear is punctured for examination of the fluid early in the course of the illness, the fluid is usually thin and yellow (serous); later in the course, the fluid becomes more viscid and adhesive (glue-like), and the eardrum may appear retracted. Some authorities believe that production of fluid of these two consistencies is caused by different mechanisms rather than by differences in duration of illness,74 but this remains unproved.

A spinal fluid leak into the middle ear is a rare cause of unilateral middle-ear fluid and can result from head trauma or without any recognized injury.75

Possible Mechanisms

Eustachian Tube Dysfunction

For all practical purposes, all children from birth to age 4 or 5 can be considered to have some degree of eustachian tube dysfunction, as the innervation of the tensor veli palatini muscle is not complete. A subset of children has very poor function: obstruction, reflux, and failure to clear middle-ear fluid are the most common dysfunctions. For example, cleft palate is invariably associated with OME secondary to eustachian tube dysfunction.76

Other Mechanisms

Risk of recurrent or chronic middle-ear infections may also occur or be increased by mechanisms independent of eustachian tube dysfunction. Defects of mucociliary action77 or of protective immunologic mechanisms of the middle ear may also be involved in infection in the absence of true obstruction. The clearing of the middle-ear fluid of bacteria in H. influenzae or S. pneumoniae infection is closely related to whether a specific antibody can be found in the fluid.78 Therefore, some children with immunoglobulin deficiencies have frequent otitis media (see Chapter 23). Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and day-care attendance both increase the risk of AOM. Breast-feeding is protective against AOM, probably because of the transfer of secretory IgA as well as a more upright feeding position in comparison to bottle-fed infants.79

Allergy

Disordered Mucous Production or Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

Patients with cystic fibrosis are at risk of frequent otitis media. Ciliary dysmotility as a predisposing factor in frequent AOM is discussed in the section on primary ciliary dyskinesia, later in this Chapter (and in Chapter 23).

Infectious Causes

Recurrent Otitis

The bacteria in recurrent AOM are the same as those in a single first episode, except that in children who have undergone multiple courses of antibiotic therapy, the causative agents tend to become increasingly resistant over time.82 Second episodes are more often new infections with a different pathogen than they are recrudescences of the old pathogen.

Chronic Otitis Media

Typically, these patients have had several courses of different antibiotics, so the nasopharyngeal flora and the middle-ear fluid often contain resistant bacteria. P. aeruginosa was recovered frequently on tympanocentesis in one study of 36 children with chronic otitis media.83 Another study found H. influenzae most frequently in serous effusions (62%) and S. epidermidis (42%) in mucoid effusions.84 S. aureus, viridans group streptococci, S. pneumoniae, enteric gram-negative rods, and anaerobes were also frequent. Bacteria have been recovered from tympanocenteses in the absence of middle-ear effusions in a carefully done study.74

Chronic suppurative otitis (CSOM) that has been treated with numerous courses of conventional antibiotics often is caused by penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae. Many samples are culture negative.

When faced with a child with chronic draining ears despite multiple courses of antibiotics, the clinician should make sure the child does not have mastoiditis. An ENT specialist should examine the patient, and careful cultures should be obtained. Intravenous clindamycin and gentamicin should provide adequate antibiotic coverage pending the results of culture. Topical antibiotic drops may be simultaneously administered.

Viral or Mycoplasmal Infections

Viruses are certainly a cause of AOM, as described earlier. Viral or mycoplasmal infections have been proposed as a possible cause of OME, but there is little evidence to support this notion. Viral cultures of serous ear fluid rarely reveal a virus.85 Outbreaks of some viruses have, however, been temporally associated with an increased frequency of OME.85

Chlamydia

Recurrent otitis media occurs twice as frequently in infants born to women who had chlamydia in the cervix.86

Other

Although M. tuberculosis is a rare cause of chronic otitis media, it is important to identify.87 A chronically draining TM is usually found, often with associated hearing loss and sometimes with unilateral facial palsy.88 Nontuberculosis mycobacteria and fungi are also occasional causes of CSOM and require specific culture mediator detection.

Treatment and Prevention

Culture of the ear drainage is sometimes helpful as a guide to antibiotic therapy in chronic otitis media. If there is a permanently perforated eardrum, the organisms often enter the middle ear from the outside, and enteric bacteria or S. aureus may be found. Systemic antibiotic therapy is often indicated for CSOM, but the perforation should be repaired if possible. Occasionally, the discharge is a primary foreign-body response to a tympanostomy tube. In this case, removal of the tube will usually result in abatement of the discharge.

A study comparing topical ofloxacin otic solution to oral amoxicillin-clavulanate for the child with tympanostomy tubes and AOM showed no significant difference in the cure rate.89 Topical ofloxacin has good activity against Pseudomonas and is thus usually effective for cases of CSOM in children with tympanostomy tubes as well. Rarely, intravenous antipseudomonal agents are required.69

Chemoprophylaxis

In the recent past, children with frequent episodes of AOM were often given chemoprophylaxis to prevent the development of new episodes. Ampicillin was shown to be effective for prophylaxis of native Alaskan children with frequent purulent otitis media.90 Chemoprophylaxis with sulfisoxazole was more effective than placebo in a study of New York children with frequent otitis media.91 However, in this era of increasing antibiotic resistance among the organisms that cause otitis media, some experts question the wisdom of initiating chemoprophylaxis under any circumstances. In essence, chemoprophylaxis is designed to provide a continuous low concentration of antibiotic in the middle-ear space, a condition that, at least in theory, maximizes the chances of developing antibiotic resistance. There are no prospective trials evaluating whether chemoprophylaxis actually produces more antimicrobial resistance, but the setting is certainly ideal. Thus maximizing treatment by episode, and referring the most refractory patients for myringotomy tube placement is often a better option than chemoprophylaxis.

Vaccine Prophylaxis

The use of the polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine has not proved efficacious92 in the prevention of recurrent otitis media, except perhaps in asthmatic children.93 However, the protein-conjugate pneumococcal vaccine is immunogenic in both otitis-free and otitis-prone children.94 The vaccine also decreases, albeit modestly, the incidence of otitis media in vaccine recipients.94a All of the major serotypes of the pneumococcus that cause otitis media are in the conjugate vaccine, and presumably good antibody titers to these pathogens should be helpful in the host defense against otitis media. In some studies vaccination against influenza virus has been shown to decrease the incidence of AOM in children by approximately 30%.95 However, a repeat randomized controlled trial failed to demonstrate a reduction in AOM in children give a inactivated influenza vaccine.95a

Other Therapy

Antihistamines and nasal decongestants are of unproved value, either alone or in combination.96 An antihistamine was no better than placebo in one study of treatment and prevention of OME.97 There is not much evidence supporting the pathogenic role of allergies in OME; therefore, most experts do not recommend referral to an allergist, even for those who seem allergy prone. Obviously, allergen avoidance pays other dividends to these patients.

Cigarette smoke exposure should be minimized. If possible, day-care attendance should be kept to a minimum, and children should be enrolled in small day-care centers if available. Breast-feeding should be encouraged. There is no scientific evidence to support claims that alternative therapies, such as chiropractic manipulation, homeopathy, or naturopathic remedies, provide any benefit to patients with frequent otitis media.32,46a Two studies from the same group showed that children who chew xylitol-containing gum have a reduced incidence of otitis media,98,99 unfortunately, the age group that has the highest incidence of recurrent otitis media is too young to obtain these benefits.

Cigarette smoke exposure should be minimized. If possible, day-care attendance should be kept to a minimum, and children should be enrolled in small day-care centers if available. Breast-feeding should be encouraged. There is no scientific evidence to support claims that alternative therapies, such as chiropractic manipulation, homeopathy, or naturopathic remedies, provide any benefit to patients with frequent otitis media.32,46a Two studies from the same group showed that children who chew xylitol-containing gum have a reduced incidence of otitis media,98,99 unfortunately, the age group that has the highest incidence of recurrent otitis media is too young to obtain these benefits.

Stopping the practice of allowing the baby to suck from a bottle while supine (bottle-propping) may eliminate many situations of recurrent otitis media.100

Complications

Hearing Impairment

Serial audiometric examinations of patients with AOM indicate some temporary hearing loss in the majority and persistent hearing loss in about 12%.101 Because of the correlation between the appearance of the eardrum and hearing loss, audiometry should be considered at 6 and 12 months after a protracted episode of middle-ear space disease,102 as such hearing impairment could potentially result in substantial learning and speech acquisition delays if not recognized.103

Extension of Infection

Brain abscess, meningitis, and lateral sinus thrombosis are rare sequelae of otitis media because the use of antibiotics has become widespread.104 Mastoiditis (discussed later) is much more common than any of the preceding complications. The occurrence of infection in contiguous spaces other than the mastoid is rare, even in countries that do not routinely prescribe antibiotic therapy for children with otitis media.30

Paralysis

Facial nerve paralysis or oculosympathetic nerve paralysis (constricted pupil with ptosis) is rare but has been reported.105

Vestibular Symptoms

Occasionally, children with otitis media present with balance problems secondary to involvement of the vestibular system.106

Cholesteatoma

An enlarging mass of stratified squamous epithelium, a cholesteatoma is dangerous because it is invasive and can erode bone. It can begin with an invagination or perforation of the tympanic membrane. It usually is related to chronic adhesive middle-ear infection.107 Adhesive OM refers to a condition caused by healing of chronic inflammation in the middle ear that leads to proliferation of fibrous tissue in the mucosal lining and impairment of ossicular movement. Rarely, a cholesteatoma is congenital108 or the result of implantation of tympanostomy tubes.109 On otoscopic examination, a cholesteatoma appears as white, shiny, greasy debris behind the tympanic membrane, often accompanied by foul-smelling discharge. It cannot be cured by antibiotics but must be removed surgically before it becomes infected and allows infection to spread to bone or brain. Cholesteatoma is usually a silent, painless disease.

Otitic Hydrocephalus

Bulging of the anterior fontanelle may be a complication of severe bilateral otitis media.110 It can be secondary to increased intracranial pressure with spontaneous recovery, or less commonly, a result of lateral sinus thrombosis.

Referral to an Otolaryngologist

For myringotomy for unusually severe pain, concurrent intracranial suppuration, or a suspected unusual pathogen in an immunosuppressed child. Myringotomy may also be indicated for children with persistence of acute symptomatic otitis media that progresses or fails to improve at all after reasonable first- and second-line therapy. In this case, myringotomy is not performed simply to allay symptoms, but to provide material for culture and antibiotic sensitivities. The timing of referral for this procedure may depend somewhat on the prevalence and severity of antibiotic-resistant pneumococcal

isolates in a practitioner’s patient population. In general, there is a higher percentage of resistant organisms among patients with frequent otitis media, a history of recent broad-spectrum antimicrobial use, and day-care attendance. Even children who have never had even a single course of antibiotics may harbor drug-resistant organisms if they attend a day care or reside with siblings with recent antibiotic use.115 Simple myringotomy in the office is usually not sufficient to facilitate adequate drainage of an effusion that persists after an ordinary episode of AOM.116

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree