Diarrheal disease

Keith B Armitage MD

Dalia El-Bejjani MD

Introduction

Infectious diarrhea is a disease of historical significance, and continues to be an important clinical problem in a variety of settings. Worldwide diarrhea accounts for more than 2 million deaths annually, and continues to be a significant contributor to childhood mortality in the developing world. In developed countries, new and emerging pathogens such as Escherichia coli 0157:H7 and large-scale outbreaks of viral gastroenteritis have focused media attention on diarrheal illnesses and have stimulated scientific inquiry. In the United States, an estimated 210 to 375 million episodes of acute diarrhea occur each year, and these episodes are associated with more than 900,000 hospitalizations and 6000 deaths annually. The cost for all food-borne illness in the United States is estimated at over 30 billion dollars. Diarrhea remains the most common illness in travelers from industrialized countries to the developing world.

Recent developments include the recognition of new and emerging pathogens, a greater understanding of the pathogenesis of some conditions, and a changing epidemiology and prevalence of enteric pathogens. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) is epidemic in health care settings in many parts of the world, with an apparent increasing prevalence and lethality. Antibiotic resistance among enteric pathogens is a growing problem worldwide, limiting treatment options for bacterial pathogens for travelers and other patients. In the western world, epidemics of noroviruses (the newer name for the ‘Norwalk’ family of caliciviruses) are increasingly well documented, and our understanding of factors in susceptibility and pathogenesis of this family of viruses is growing. New and emerging protozoan pathogens such as Cyclospora and Cryptosporidium are increasingly recognized in travelers and domestic outbreaks. In the United States, food-borne diarrheal illness continues to impose a significant burden of disease. In this chapter we will review significant recent literature that highlights these and other developments in infectious diarrhea.

Clostridium difficile

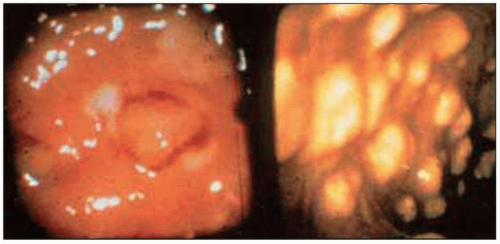

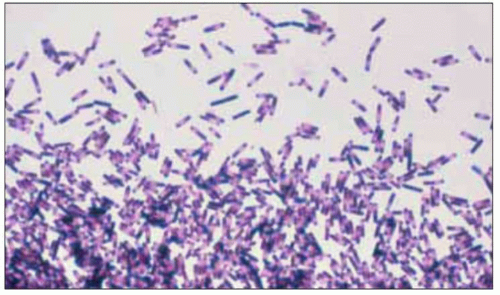

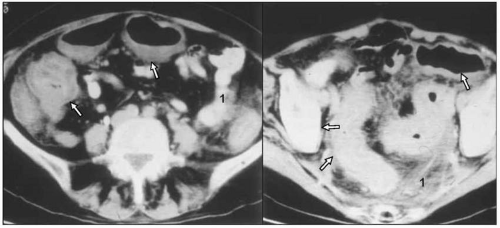

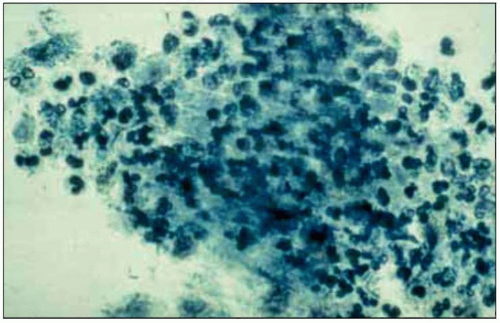

Although Clostridium difficile has been recognized as the cause of CDAD for many years, recent evidence of a significantly increasing prevalence of illness due to C. difficile makes this truly an emerging infection. Antibiotic-associated colitis has been recognized since the advent of the antibiotic era, and C. difficile was originally reported as an agent of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in 1977. The gastrointestinal tract hosts a very complex ecosystem of microbes that act as a barrier against microbial pathogens. C. difficile diarrhea results from the suppression of the normal flora in the colon, which allows overgrowth of C. difficile and production of cytopathic toxins. C. dfficile is a Gram-positive, sporeforming rod (Figs. 6.1, 6.2). In the modern era, C. difficile is recognized as a major cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea, the basis for >99% of pseudomembranous colitis (Figs. 6.3, 6.4), and the leading cause of diarrhea in hospitalized patients. In most cases, CDAD produces an inflammatory diarrhea, with the stool positive for fecal leukocytes (Fig. 6.5). Recent reports have provided evidence of an epidemic of CDAD in North America1. The study from Sherbrooke, Quebec is the most recent large study to examine the population-based incidence of CDAD. The authors demonstrate an increase in the incidence of

CDAD over the past decade, with a striking increase in the number of cases in elderly patients in 2003. Their report also provides evidence that the mortality associated with CDAD has increased, particularly among the elderly. Increasing nosocomial spread, changing patterns of antibiotic use, spread of more pathogenic C. difficile strains, and higher numbers of immunocompromised patients are cited as reasons for the increase.

CDAD over the past decade, with a striking increase in the number of cases in elderly patients in 2003. Their report also provides evidence that the mortality associated with CDAD has increased, particularly among the elderly. Increasing nosocomial spread, changing patterns of antibiotic use, spread of more pathogenic C. difficile strains, and higher numbers of immunocompromised patients are cited as reasons for the increase.

Fig. 6.1 Gram stain of Clostridium difficile demonstrating Gram-positive, spore-forming rods. C. difficile-associated diarrhea is epidemic in hospitals in North America. (Courtesy of Dr D Bobak.) |

Fig. 6.4 CT scan showing dilated and thickened colon (arrow, colon wall; 1, pericolonic fat). Most patients with Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) do not have pseudomembranes, but when they are seen on a CT in a patient with CDAD the appearance on the CT scan can establish the diagnosis. (Courtesy of Dr R Salata.) |

Fig. 6.5 Stool prep showing abundant fecal leukocytes from a patient with Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD). Fecal leukocytes are usually present in CDAD, and in patients with inflammatory colitis from bacterial pathogens such as Salmonella, Campylobacter and Shigella. Pathogens that produce illness without producing intestinal inflammation are not associated with fecal leukocytes. Pathogens that typically produce diarrheal illness without fecal leukocytes include viruses, enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, cholera, Giardia, Cryptosporidium, and Cyclospora. (Courtesy of Dr R Salata.) |

The authors also reported evidence that CDAD may be becoming a more lethal disease; in their study the proportion of patients who died within 30 days of the diagnosis increased to 13.8% in 2003 from 4.7% in 1991. Many experts believe that the incidence of more severe cases of CDAD represents clonal expansion of more lethal strains. We anticipate that publications addressing this issue will appear in the near future. These authors also found an association between a better outcome and vancomycin as the initial therapy in severe cases. Further studies specifically designed to address this issue are needed.

A final emerging issue with CDAD is the association with classes of antibiotics not previously associated with CDAD. Clindamycin was the classic antibiotic associated with illness due to C. difficile and, in recent years, beta-lactams, particularly advanced generation cephalosporins, and beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations have been frequently implicated in CDAD. The common theme among antibiotics associated with CDAD is antimicrobial activity against intestinal anaerobes but no activity against C. difficile. Antibiotics whose antimicrobial spectrum does not include robust activity against gut anaerobes are much less frequently associated with CDAD. Ciprofloxacin was the first fluoroquinolone to gain widespread clinical use. There have been case reports associating ciprofloxacin with CDAD, but clinical experience and published data have not implicated ciprofloxacin as a frequent cause of CDAD. Beginning in the late 1990s, advanced generation quinolones, including levofloxacin, gatifloxacin, and moxyfloxacin, gained widespread use for a variety of infections. Unlike ciprofloxacin, the advanced generation fluoroquinolones have broader activity against anaerobes, and clinical experience and anecdotal reports associating the new quinolones with CDAD have been reported. Several recent papers have demonstrated that fluoroquinolone use was strongly associated with CDAD2. The advanced generation fluoroquinolones are active against anaerobes but lack activity against C. difficile.

Travelers’ diarrhea

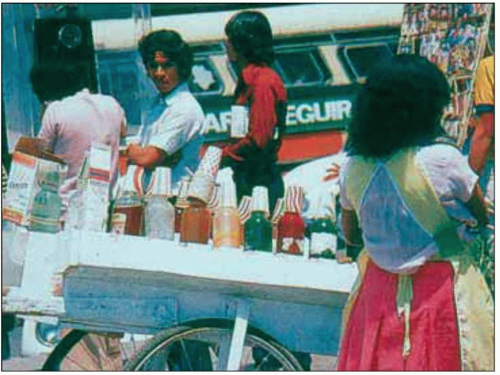

Between 20% and 50% of individuals traveling to developing countries will develop diarrhea during or shortly after their trip. The risk is highest when traveling to India, Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and south Asia. The average duration of an episode of travelers’ diarrhea is 3-6 days. About 10% of episodes last longer than 1 week. Basic precautions, such as avoidance of unsafe water and uncooked food, can significantly decrease the risk of diarrhea in travelers. Water or food from street vendors, for instance, is among potential high-risk exposures (Fig. 6.6).

An emerging issue with travelers’ diarrhea is the possible association with post-diarrhea irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which could potentially alter the strategy for preventing and treating travelers’ diarrhea. The most commonly used strategy for short-term visitors to developing countries is to provide an antibiotic for

‘presumptive therapy’, to be taken if diarrhea develops. Presumptive therapy has been shown to be effective in clinical trials in quickly attenuating and resolving the diarrhea. This strategy has the advantage of limiting antibiotic use to those travelers that develop diarrhea. Travelers’ diarrhea treated with this strategy is thought to be self-limited with no significant long-term consequences. In the past 20 years a number of studies have associated acute bacterial gastroenteritis with the subsequent development of IBS. It is hypothesized that infectious gastroenteritis might cause chronic low-grade inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract leading to IBS. IBS complicating otherwise self-limited travelers’ diarrhea has been reported, but the incidence and prevalence of IBS complicating travelers’ diarrhea are not known. A recent study looked prospectively at the incidence of IBS 6 months after an episode of travelers’ diarrhea3. The authors show that infectious gastroenteritis is a potential risk factor for IBS but fail to demonstrate an association with a specific pathogen. Further studies with longer duration of follow-up are needed to evaluate the natural course of post-infectious IBS. The authors do not want to overstate the potential association between IBS and travelers’ diarrhea, but include it as an emerging issue.

‘presumptive therapy’, to be taken if diarrhea develops. Presumptive therapy has been shown to be effective in clinical trials in quickly attenuating and resolving the diarrhea. This strategy has the advantage of limiting antibiotic use to those travelers that develop diarrhea. Travelers’ diarrhea treated with this strategy is thought to be self-limited with no significant long-term consequences. In the past 20 years a number of studies have associated acute bacterial gastroenteritis with the subsequent development of IBS. It is hypothesized that infectious gastroenteritis might cause chronic low-grade inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract leading to IBS. IBS complicating otherwise self-limited travelers’ diarrhea has been reported, but the incidence and prevalence of IBS complicating travelers’ diarrhea are not known. A recent study looked prospectively at the incidence of IBS 6 months after an episode of travelers’ diarrhea3. The authors show that infectious gastroenteritis is a potential risk factor for IBS but fail to demonstrate an association with a specific pathogen. Further studies with longer duration of follow-up are needed to evaluate the natural course of post-infectious IBS. The authors do not want to overstate the potential association between IBS and travelers’ diarrhea, but include it as an emerging issue.

The potential for post-travelers’ diarrhea IBS may cause a re-evaluation of presumptive therapy. The availability of effective new luminal agents may make a preventive strategy more feasible. Rifaximin, a luminal, gastrointestinal-selective oral antibiotic, was approved for the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea in 2004. Rifaximin is primarily indicated for enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) in travelers to developing countries (Fig. 6.6). ETEC is the most frequent bacterial cause of travelers’ diarrhea worldwide and especially in Latin America. It usually causes a secretory-type diarrhea through its heat-labile toxin, which structurally resembles the cholera toxin. Diarrhea due to ETEC usually responds to treatment with quinolones, trimethoprim sulfa, and cephalosporins. Rifaximin is an alternative therapy for travelers’ diarrhea due to E. coli (the most common pathogen), but has limited activity against other common pathogens. A recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial by DuPont et al. looked at efficacy of rifaximin in preventing travelers’ diarrhea in US students visiting Mexico5. This study showed that rifaximin significantly prevented diarrhea as compared to placebo; it was also found to be well tolerated with minimal effect on enteric flora. More studies are under way to evaluate the role of rifaximin in areas of the world where ETEC is not the most frequent isolate.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree