John N. Galgiani

Coccidioidomycosis (Coccidioides Species)

Although the systemic fungal infection now known as coccidioidomycosis has been recognized for more than a century,1 it has become more prevalent throughout the nonendemic and endemic regions of the world.2 A medical intern is credited with first identifying in 1892 a patient who had widespread disease.3 Organisms seen microscopically were mistakenly thought to be parasites, and only several years later was the true mycotic etiology determined and the agent given the name Coccidioides immitis.4 For 3 decades, coccidioidomycosis was thought to be a rare and nearly always fatal infection. In 1929, an accidental laboratory exposure of a medical student at Stanford University resulted in only a transient respiratory infection. His unexpected survival stimulated a reassessment of the natural history of coccidioidal infections, which soon led to the recognition that a common respiratory condition in the San Joaquin Valley of California (valley fever) was the more usual result of infection.5 This conclusion was corroborated with the development by Smith and colleagues6 of a specific skin test and serologic assays for coccidioidomycosis. With these tools, the clinical spectrum was well described by the mid-1950s (an excellent monograph published by Fiese7 remains a valuable contemporary reference on the disease).

The reemergence of coccidioidomycosis can be attributed to changes in demography and in contemporary medicine.8 First, the populations at risk of exposure are greatly expanded. Regions in which Coccidioides spp. are endemic, which previously were sparsely populated, now encompass major metropolitan centers such as Phoenix, Arizona. Many of those relocating to the Southwest are retirees, and case rates in older persons are higher than in young adults.9 With this population growth has come greatly increased tourism and commerce-related movement of people into and out of endemic areas. As a result, increased numbers of people are acquiring coccidioidal infections both within and beyond endemic regions.10,11 Second, a major segment of the population has emerged with compromised cellular immunity because of either underlying diseases or immunosuppressive therapies to control other diseases.12,13,14,15–28 These patients are unusually susceptible to serious coccidioidal infections, and as a result, the severity of coccidioidal infections as a public health problem has increased. Third, advances in prevention and treatment of fungal infections offer new opportunities for management. These trends have made coccidioidomycosis more relevant to physicians everywhere.29 Finally, the emergence of Coccidioides spp. as potential agents of bioterrorism was identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1997. Since then, awareness of this possibility has become even greater with the increased incidence of terrorism as an international tactic and because of technical advances in genetic transformation, which adds to the potential to use Coccidioides spp. as a biological weapon.30–33

Mycology

Coccidioides spp. are dimorphic fungi that exist as either mycelia or as unique structures known as spherules.34 Both forms of growth are asexual, and it is not possible to classify Coccidioides spp. in relation to other fungi by classic taxonomy. By molecular analysis, however, Coccidioides spp. appear related most to other ascomycetes, most closely to the medically important organisms Blastomyces dermatitidis and Histoplasma capsulatum.35 Although a sexual phase has not been found, population genetic studies suggest that one does exist.36,37 Two genetically distinct populations have been identified among the etiologic agents of coccidioidomycosis. The occurrence of two populations was correlated with separate endemic regions where patients resided. This finding prompted classification of the previously known single species, C. immitis, into two species: C. immitis and Coccidioides posadasii. Most of the C. immitis isolates have been obtained from California, whereas C. posadasii isolates have been obtained from patients in other states and from countries other than the United States.38 DNA sequence analysis of C. posadasii strains enabled investigators to deduce the approximate geographic origin of some infections.39,39a The two species have shown few phenotypic differences; the clinical manifestations resulting from infection with either species appear the same, and in vitro susceptibility to antifungals is similar.40,41 Molecular identification methods for differentiation of C. immitis from C. posadasii have been described41 but are not yet routinely employed. Thus, references in the literature to C. immitis may actually be referring to either species. Isolates for which the species has not been determined are best designated as simply Coccidioides spp., which is the convention followed in this chapter.

Mycelial (Saprobic) Growth

On routine microbiologic nutrient agar media and presumably in the soil, Coccidioides spp. grow as mycelia by apical extension, and true septa form along its course. Maturation within 1 week of growth results in alternating mycelial cells’ undergoing a process of autolysis and thinning of the cell walls. The remaining cells (arthroconidia), which become barrel-shaped and approximately 5 µm in length, develop a hydrophobic outer layer and become capable of remaining viable for long periods. Because the attachments of arthroconidia to adjacent cell remnants are fragile, they are prone to separation by physical disruption or mild air turbulence. As a result, arthroconidia become airborne in a form capable of deposition in the lungs if inhaled.

Spherule (Parasitic) Growth

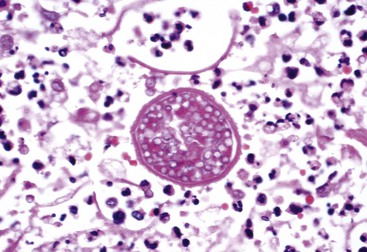

In the lungs, arthroconidia remodel into spherical cells, shedding their hydrophobic outer wall.42,43 During this phase, nuclear division and cell multiplication occur and septa extend from the internal surface of the wall to transect the growing spherule into scores of subcompartments, each containing viable daughter cells or endospores. In tissue, spherules can become 75 µm in diameter (Fig. 267-1). Spherules grown in vitro demonstrate nuclear division throughout maturation, although their size is smaller and the number of endospores is fewer.44 As a spherule matures, its outer wall thins and eventually ruptures. Early in the course of experimental infections, this rupture occurs in approximately 4 days, and with the release of endospores, the number of viable fungal units is amplified by approximately 100-fold, each of which may continue to propagate in tissue or revert to mycelial growth if removed from the site of an infection.

Epidemiology

Geographic Range

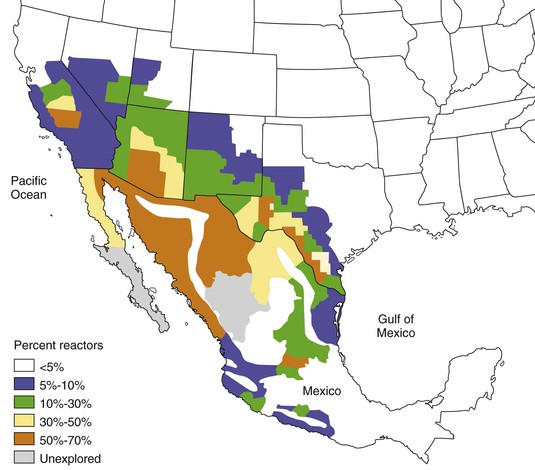

Coccidioides spp. are endemic to the soils of only certain regions of the Western Hemisphere, nearly all of which are within the north and south 40-degree latitudes. Well-described transport of arthroconidia, either in soil on fomites45–46a or as the result of unusually severe dust storms,47 has produced infections in persons without endemic exposure, but this generally has not led to the establishment of new areas of endemicity. Regions of the United States in which Coccidioides spp. are endemic are shown in Figure 267-2. Noncontiguous foci of endemicity also exist such as that studied at Dinosaur National Monument, Utah48 and in eastern Washington.39a These regions generally have the characteristics of the “lower Sonoran life zone,” which include an arid climate, yearly rainfall of 5 to 20 inches, hot summers, winters with little freezing weather, and alkaline soil. Other areas where Coccidioides spp. have been identified include Mexico (adjacent to the U.S. border; western portions of Sonora, Nayarit, Jalisco, and Michoacan; central regions, including Coahuila, Durango, and San Luis Potosi); Central America (Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua); and South America (Argentina, Paraguay, Venezuela, Colombia, Brazil).49 An archeological investigation has provided evidence that Coccidioides spp. infected bison 8500 years ago in Nebraska, far beyond the current endemic regions.50 This raises the possibility that climatic change could potentially affect the geographic distribution of Coccidioides spp.

Within the endemic regions, the likelihood of finding Coccidioides spp. in soil samples varies considerably among different locations37,51 and different seasons. The fungus is recovered most easily toward the end of winter rains.52 This is opposite to the seasonal relationship for acquisition of new infections, which in California and Arizona occur most frequently during the summer months, after the soil has become dry. In Arizona, there is a second peak of new clinical infections from October until the winter rains, which corresponds to a similar dry period after the late summer rains in that region.53 Colonies of Coccidioides spp. are sparsely distributed within the endemic region and only a small proportion of soil samples yield coccidioidal growth.51

Rates of Coccidioidal Infection

Prevalence surveys in the 1950s of skin test reactivity to coccidioidal antigens in school-aged children of California’s central valley suggested that the annual risk of infection was approximately 15%.54 Smith and colleagues55 showed that in 25% to 50% of military personnel in the San Joaquin Valley, skin test results converted to positive during a single year. More contemporary estimates from the same areas in California and from Tucson, Arizona, indicate that the risk has declined to approximately 3% per year.54,56 Because of these lower rates and because of the large influx of new residents to the endemic regions from nonendemic locales (in 2010, estimated to total >7 million persons for southern Arizona and southern central California), the proportion of persons within the endemic region with prior infection is approximately 30%. The expected number of infections is on the order of 150,000 annually.

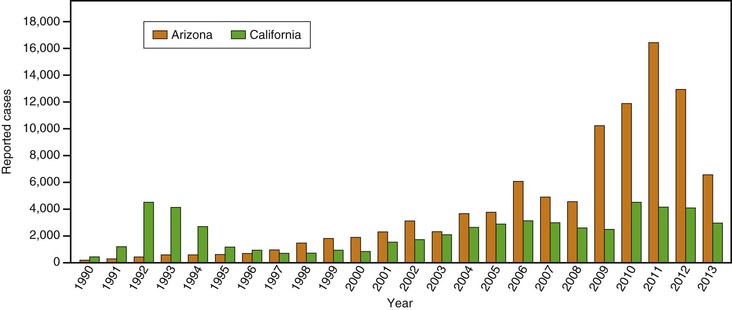

The numbers of infections reported to state departments of public health differ significantly from year to year. Some variation has been associated with total winter rainfall; more cases occur in the summers after wetter winters.57 On occasion, epidemics also have been associated with disruption of infected soil, by human intent, such as with excavation58; after natural events, such as severe dust storms or earthquakes59; or during military maneuvers.60 Some fluctuations in rates of infections are not explained, however. Such is the case for an exceptionally large epidemic in California’s Central Valley in the period 1992-1995, in which the incidence of infection at times was more than 10 times that normally reported.61 Since the second half of the 1990s, the incidence has also increased in Arizona (Fig. 267-3).10,62

Pathogenesis and Control

Nearly all infections are the result of inhaling arthroconidia. Cutaneous inoculations have been reported, producing lymphatic extension to regional lymph nodes and resolving without treatment. These occurrences are exceedingly rare, however.63

A single arthroconidium may be sufficient to produce a naturally acquired respiratory infection. This is the case for experimental infections in mice,64 and air sampling within coccidioidal endemic regions suggests that the ambient density of arthroconidia in the air is low.65,66 The size of the arthroconidium would allow its deposition within the terminal bronchiole but probably not as deeply as the alveolar space. After an arthroconidium transforms into rupturing spherules, inflammation ensues, forming a local pulmonary lesion. Extracts of Coccidioides spp. have been shown to react with complement, releasing mediators of chemotaxis for neutrophils.67 In some infections, Coccidioides spp. leave the lungs to establish disseminated lesions in other parts of the body. In this sequence of events, fungal elements must move from the distal bronchiole into the lung parenchyma, gain entry into the vascular space, and leave the vascular space to create extrapulmonary sites of infection. It is possible that endospores within macrophages travel through lymphatic vessels to the bloodstream, as has been described for dissemination of tuberculosis and histoplasmosis. This possibility is also compatible with the common finding of infected hilar, peritracheal, supraclavicular, and cervical lymph nodes in patients with extrapulmonary coccidioidal infections.68

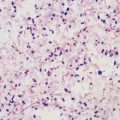

Histopathology

Microscopic examination of tissue infected with Coccidioides spp. shows elements of acute and chronic inflammation. Acute inflammation, including neutrophils and eosinophils, is associated with active infections and rupturing spherules.68,69 Granulomatous lesions that include lymphocytes, histiocytes, and multinucleated giant cells are associated with chronic or arrested infections and with mature unruptured spherules.70 In patients with widespread infections, it is common to find both inflammatory responses represented concurrently at different anatomic sites.

Host Defenses

Control of coccidioidomycosis depends on T lymphocytes. This conclusion is supported by studies of experimentally produced infections in mice71–75 and by the increased severity of naturally acquired infections in T-cell–deficient patients.13,14,15,21,22–25 Peripheral mononuclear blood cells from patients with disseminated coccidioidomycosis have virtually no interferon-γ response to coccidioidal antigens.76 This is in contrast to the brisk stimulation of similar leukocyte preparations from patients in whom coccidioidal infections are competently controlled and who have delayed-type dermal hypersensitivity to coccidioidal skin-testing antigens.77–79,80,81 These findings are consistent with an absent type 1 helper T cell (Th1)-type response described in some experimental animals82,83 and human infectious diseases in which cellular immunity plays a role. In humans, however, despite the observed depression of interferon-γ levels, interleukin-4 and interleukin-10 levels were not reciprocally elevated,77 which would be indicative of a type 2 helper T cell (Th2) response. Recently, specific mutations in Th2 pathway genes have been associated with disseminated infection.78–79a

In addition to T cell–mediated control of infection, innate cellular responses may contribute to host defense. Inhibition of growth of Coccidioides spp. can be shown in vitro by human neutrophils and mononuclear cells from persons with or without prior coccidioidal infection as judged by skin test reactivity to coccidioidal antigens.84 Although neutrophils do not seem to be fungicidal against Coccidioides spp., mononuclear cells or natural killer cells have been shown to reduce fungal viability.85,86 These innate cellular inhibitory effects are most evident against arthroconidia or endospores and are lost as spherules increase in size and mature.87 These in vitro observations can be extrapolated to indicate that innate defenses may serve primarily to slow fungal proliferation after infection, transforming what otherwise might be a more fulminant infection to a more subacute or chronic process.

Coccidioidal infections engender a variety of humoral responses to several different antigens in patients, and, as discussed subsequently, several are diagnostically useful. Coccidioides-infected B cell–deficient mice are not as protected by vaccination as are normal mice.88 However, a specific defensive role for immunoglobulins has thus far not been defined.

Clinical Manifestations

At least half to two thirds of all infections caused by Coccidioides spp. are either inapparent or sufficiently mild not to prompt medical evaluation.55 Of those that do become medically significant, a large majority result in a respiratory illness that is indistinguishable without specific testing from community-acquired pneumonia caused by other entities.89 In an observational study in southern Arizona, coccidioidomycosis was estimated to be responsible for approximately one third of all cases of community-acquired pneumonia in that endemic area.90,90a Nonetheless, misunderstandings of the manifestations of coccidioidomycosis or the perceived unimportance of diagnosis of early infections has led to gross disparities between the numbers of expected and reported coccidioidal infections.91–93 For example, the number of coccidioidal infections reported to Arizona’s Department of Health Services (see Fig. 267-3) represent only a fraction of the expected 30,000 new illnesses. Underdiagnosis may be even more likely for patients with coccidioidomycosis evaluated outside the endemic region.58,94 Most coccidioidal infections, whether detected or not, follow a self-limited course; only a few produce residual sequelae or chronic progressive infections. Although complications are typically manifested within weeks or up to 2 years after the original infection, the severity of the initial respiratory infection is not correlated with the likelihood of complications. In this context, the identification of even mild primary infections takes on added significance and clinical relevance.

Early Respiratory Infection

The first symptoms of the primary infection usually appear 7 to 21 days after exposure. Most infections seem to develop as a result of exposure to small numbers of arthroconidia; however, when exposure is unusually intense, symptoms are more likely to appear early. In an epidemic of coccidioidomycosis that occurred in the San Joaquin Valley of California between 1991 and 1994,95 the findings in 536 patients with new infections included cough (73%), chest pain (44%), shortness of breath (32%), fever (76%), and fatigue (39%). These findings are typical of earlier reports. Although the infection is often subacute in development, patients occasionally report abrupt onset of symptoms, especially that of pleurisy. Weight loss is also a common sign, and headache has been noted in 21% of patients in the absence of meningeal infection.53 Skin manifestations develop as part of the primary illness. Most frequent and easily missed is a nonpruritic fine papular rash that occurs early and transiently during the illness. More striking are erythema nodosum and erythema multiforme, which occur predominantly in women. Migratory arthralgias are also common complaints, and the triad of fever, erythema nodosum, and arthralgias (especially of the knees and ankles) has been termed desert rheumatism. Routine laboratory findings, including serum procalcitonin levels,95a are usually normal except for an increase in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Peripheral blood eosinophilia may be present, occasionally accounting for two thirds of the circulating leukocytes. Chest radiograph results are abnormal in more than half of patients. Common findings include unilateral infiltrates, hilar adenopathy, and pleural effusions. Persistent hilar or peritracheal adenopathy is associated with extrathoracic spread of infection. Lung cavities are present initially in approximately 8% of infections recognized in adults but are less frequent in children.

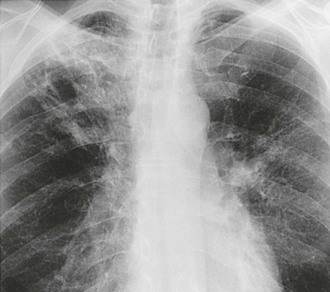

Uncommonly, coccidioidal pneumonia manifests as a diffuse process leading to respiratory failure, either because of high-inoculum exposure96–99 or because of fungi in the bloodstream that seed the lung in many sites.22 The manifestation is often fulminant, mimicking that of septic shock or a bacterial infection, and despite treatment, the rate of mortality is high. Approximately one third of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients with clinically acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) exhibit this radiographic appearance. Although fungemia associated with diffuse pulmonary infiltrates may occur in immunologically intact patients,100 it is nearly always attributable to a recognizable cellular immunodeficiency state.101 In HIV-infected patients with fungemia, the CD4+ counts are typically less than 100 cells/mm3 and the viral load is high.

Although some of the presenting symptoms are statistically more likely to occur with coccidioidal infections than with respiratory illness of other causes, the overlap of clinical syndromes is substantial.89,90 For most patients, specific testing is necessary to secure a definite diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis.

Most coccidioidal respiratory infections resolve without complications but often take several weeks to many months to do so. When resolution of the self-limited illness is protracted, the symptom of fatigue is frequently the last to resolve. This fatigue syndrome, disproportionate to other evidence of infection syndrome, may strikingly interfere with normal daily activities or the ability to return to work and be a source of considerable distress. A few patients with infections develop various pulmonary sequelae, and even fewer patients manifest disseminated infection outside the lungs. Despite their relative infrequency, these complications pose significant difficulties in diagnosis and management (discussed later).

Pulmonary Nodules and Cavities

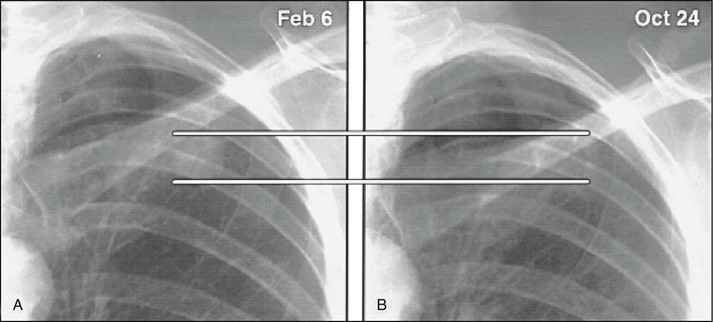

Approximately 4% of pulmonary infections result in a nodule, ranging up to 5 cm in diameter. A nodule typically causes no symptoms but may be indistinguishable from a neoplasm without histologic examination.102 On occasion, nodules liquefy and drain into a bronchus to form a cavity (Fig. 267-4).

Pulmonary cavities may be present initially or in the later stages of the primary infection. They are usually peripheral and solitary, and with time, most develop a distinctive thin wall.103 Cavities may not cause any symptoms, and half close within 2 years. Others are associated with local symptoms of pleuritic pain, cough, or hemoptysis. A fungus ball may develop within cavities, either from mycelia of Coccidioides spp.104 or with other species of fungi (Fig. 267-5). Another infrequent but well-recognized complication is rupture of a peripheral coccidioidal cavity into the pleural space and its manifestation as a pneumothorax. Ruptures commonly occur in athletic young men and are not associated with underlying immunodeficiency. Because the fungal walls of Coccidioides spp. are inflammatory, ruptured coccidioidal cavities often produce fluid in the pleural space, and the presence of an air-fluid level within the pleural space is a clue that the process is not a spontaneous pneumothorax or a ruptured pulmonary bleb (Fig. 267-6). If the cavity is diagnosed early, surgical resection of the cavity and closure of the pulmonary leak is the preferred treatment.105

Chronic Fibrocavitary Pneumonia

In contrast to thin-walled coccidioidal cavities, a chronic fibrotic pneumonic process that develops in some patients is characterized by pulmonary infiltrates and pulmonary cavitation (Figs. 267-7 and 267-8).106 This form of infection is not common among patients with T-cell deficiencies but seems to be associated with diabetes or preexisting pulmonary fibrosis related to smoking or other causes.107 Involvement of more than one lobe is more common, and these lesions may cause systemic symptoms, such as night sweats and weight loss, and local symptoms. Recently, two patients with a mutation of STAT1 have been described with a chronic consumptive coccidioidal pneumonia, which is strikingly devoid of cavitation in contrast to what occurs more commonly.79a

Extrapulmonary Dissemination

Coccidioides spp. spread beyond the lungs in approximately 0.5% of all infections in the general population. Several factors dramatically increase the risk of dissemination, however: immunodeficiency conditions, such as the later stages of HIV infection and Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and therapies that suppress immune function, such as therapy to prevent solid-organ rejection, high-dose corticosteroid therapy (equivalent to long-term prednisone doses >20 mg/day), and therapeutic inhibitors of tumor necrosis factor.* In two thirds of renal transplant recipients who developed coccidioidal infection, the infection progressed to dissemination.14,15 With transplantation, the risk is heightened mostly by either newly acquired disease or reactivation of prior infection. Transmission by the engrafted organ has been reported but is rare.16,20 Dissemination is more likely to develop in men than in women.51 Dissemination is also more likely, however, if infection is diagnosed first during pregnancy, especially during the third trimester or in the immediate postpartum period.110,111 The risk of dissemination also appears to be increased among persons of African or Filipino ancestry, although the exact magnitude of the risk is controversial.112

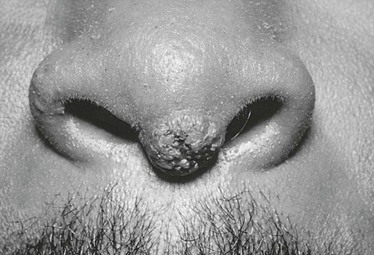

Extrapulmonary dissemination is not associated often with pulmonary complications. Many patients with disseminated coccidioidal infection have entirely normal chest radiographs. The most common site of dissemination is the skin. The range of lesions includes superficial maculopapular lesions, keratotic and verrucose ulcers, and subcutaneous fluctuant abscesses. There is a predilection for lesions at the nasolabial fold (Fig. 267-9). Although most extrapulmonary dissemination is the result of hematogenous spread, supraclavicular and cervical lymphadenopathy is also a frequent manifestation and probably represents lymphatic drainage from the primary pulmonary infection.

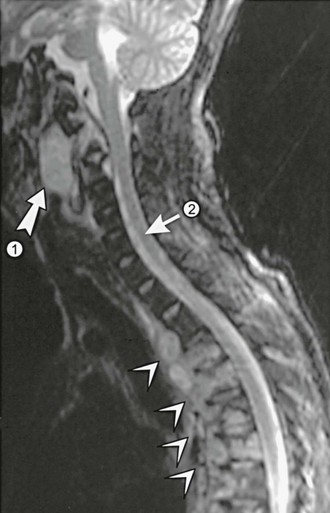

Joints and bones are common sites of dissemination. Joint infections differ from the self-limited joint complaints of desert rheumatism in that infections are typically asymmetrically distributed and are associated with a prominent synovitis and effusion. Although any joint can become infected, the knee is involved most frequently; other common locations include the joints of the hands and wrists, feet and ankles, and pelvis.113–115 Infection may be limited to the synovium or may erode to involve the underlying bone. Alternatively, bones may be involved first with secondary extension into the joint.116 Although long bones may be affected, vertebral infection is much more common. Involvement of multiple vertebrae is typical.117 These may coalesce to produce anterior or posterior paraspinous soft tissue abscesses or an epidural abscess (Fig. 267-10). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often helpful in defining the exact location of these lesions.118