Peter G. Pappas

Chronic Pneumonia

Chronic pneumonia syndrome is a pulmonary parenchymal process that can be infectious or noninfectious, has been present for weeks to months rather than for days, and is manifested by abnormal chest radiographic findings and chronic or progressive pulmonary symptoms. Abnormal chest radiography, which may reveal any of several radiologic patterns, is probably the most important consideration in the diagnosis of chronic pneumonia. Indeed, in many patients, the diagnosis is based more on the pulmonary radiographic findings than on the pulmonary symptoms. However, asymptomatic patients who have abnormal radiographic findings such as solitary or multiple nodules should not be considered to have chronic pneumonia.

The emphasis in this chapter is on the chronic pneumonias caused by infectious agents. However, it is important to recognize the importance of noninfectious causes of chronic pneumonia, including the vasculitides such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis); Churg-Strauss syndrome; Goodpasture syndrome and microscopic polyangiitis1–6; neoplastic processes such as bronchogenic carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and lymphoproliferative disorders7,8,9–14; prescription drugs, illicit drugs, and other chemicals15–24; radiation16; amyloidosis25–27; sarcoidosis28,29,30,31; pulmonary alveolar proteinosis31a and forms of lipoid pneumonia32,33,34,35; chronic organizing pneumonia and hypersensitivity pneumonitis due to a wide variety of agents36–40; and other idiopathic interstitial pneumonias.41–43

Causes

The infectious causes of chronic pneumonia can be divided into two main groups: (1) those agents that typically cause acute pneumonia and are unusual causes of chronic pneumonia and (2) infectious agents that typically cause chronic pneumonia. Among those agents that typically cause acute pneumonia, anaerobic bacteria, selected microaerophilic streptococci,44,45,46 Staphylococcus aureus, group F streptococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Burkholderia pseudomallei, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are the organisms most likely to produce a persistent chronic pneumonia. In these instances, the pneumonia reflects a chronic necrotizing process that most commonly occurs in patients with significant underlying disease (e.g., alcoholism, diabetes mellitus, intrathoracic malignancy, chronic obstructive lung disease), hospitalized patients, those requiring long-term ventilatory assistance, patients with chronic swallowing and reflux disorders, and others at risk for recurrent aspiration, such as patients with Parkinson’s disease and other neurologic disorders.44,45–55 Acute pneumonia caused by most viruses and by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella species, Coxiella burnetii, or Chlamydia pneumoniae rarely progresses to a chronic pulmonary infection.56,57

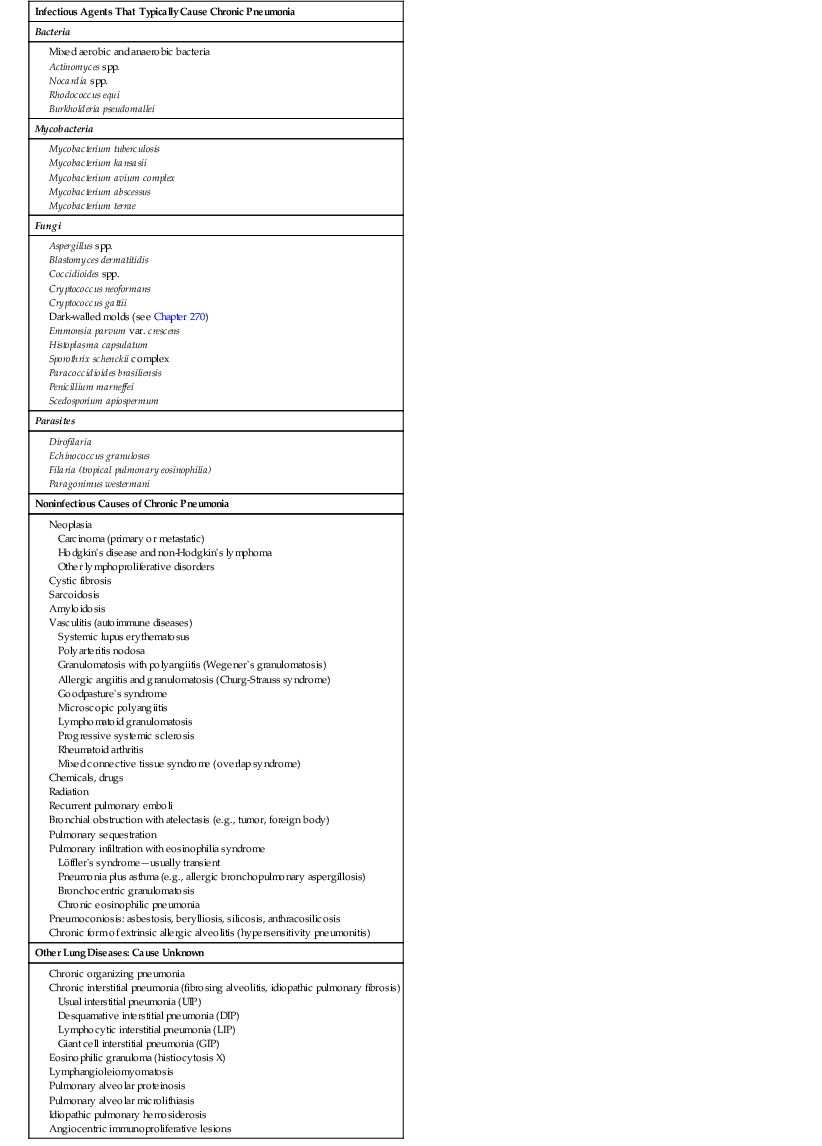

Table 72-1 lists the most common infectious and noninfectious causes of chronic pneumonia. In the otherwise healthy host, the most common considerations are tuberculosis58–61 and nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM)59,62–66,67; cryptococcosis due to either Cryptococcus neoformans or Cryptococcus gattii68–70; and the endemic fungal infections including histoplasmosis,71–73 coccidioidomycosis,74–76 and blastomycosis.77–80 In the appropriate geographic area, paracoccidioidomycosis and penicilliosis should be considered.81–83 Lung abscess with mixed aerobic and anaerobic bacterial infections may warrant consideration,45–47 as well as actinomycosis.84–87 Aspergillosis (multiple species), scedosporiosis (caused by Scedosporium apiospermum and Scedosporium prolificans),88–90 sporotrichosis,91,92 and adiaspiromycosis (caused by Emmonsia parvum var. crescens)93,94,95,96 are rare causes of chronic fungal pneumonia in the normal host. In the immunocompromised host, mycobacteria, especially Mycobacterium tuberculosis, remain common causes of chronic pneumonia.97,98 Classic opportunistic infections, including nocardiosis,99–103 cryptococcosis,69,104 aspergillosis,105,106 and infections caused by other molds such as the agents of scedosporiosis and mucormycosis, are also important in this population.107,108 In the appropriate geographic areas, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, and blastomycosis are also important considerations in immunocompromised and noncompromised hosts.73–78,109,110 In persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), coccidioidomycosis and histoplasmosis may be seen. Furthermore, in patients with AIDS, chronic pneumonia may be caused by Rhodococcus equi, Pneumocystis jirovecii, Mycobacterium avium complex, or noninfectious disorders such as Kaposi sarcoma, lymphoma, and nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis.111–117 The protozoa and helminths listed in Table 72-1 are uncommon causes of chronic pneumonia syndrome in persons living in industrialized countries, but they are important considerations for those who live in or have traveled to areas in which these agents are endemic.

TABLE 72-1

Causes of Chronic Pneumonia Syndrome

Epidemiology

Age, Gender, and Race

A detailed history is an important first step toward establishing a specific diagnosis in patients with a chronic pneumonia syndrome. The significance of age and gender for patients with chronic pneumonia from other causes also usually relates, indirectly, to relevant epidemiologic factors. For example, an older adult is at higher risk of having a cerebrovascular accident, which in turn might predispose this patient to an aspiration episode and subsequent chronic bacterial pneumonia and abscess. Older debilitated patients are at higher risk for development of chronic necrotizing pneumonia caused by aerobic gram-negative bacteria.49,51,54 Similarly, the gender of a given patient is likely to affect or determine occupation and hobbies and therefore the likelihood of exposure to certain infectious agents or other causative vehicles. Moreover, gender may predispose to certain rare chronic pulmonary disorders. For example, pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis, a cause of chronic pneumonia, is a rare neoplastic disorder that occurs almost exclusively in adolescent and young adult women.118 Racial and genetic characteristics are increasingly recognized as predisposing factors to severe disease manifestations from a variety of pathogens.82,119–121 For example, chronic cavitary pulmonary tuberculosis is more common in blacks,58,59 and disseminated coccidioidomycosis is much more likely in darker-skinned persons, including blacks, Filipinos, and Asians who have lived in or have traveled to an area endemic for Coccidioides immitis or Coccidioides posadasii.74,76 Conversely, chronic cavitary histoplasmosis is much more likely in older white men with a history of chronic lung disease.71 Fungus ball (aspergilloma) of the lung occurs in a previously existing apical cavity in patients with prior sarcoidosis, histoplasmosis, tuberculosis, or other fibrocavitary lung disease.88 Chronic necrotizing (semiinvasive) and invasive aspergillosis may occur in men with underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.88,122

Occupation and Hobbies

An example of a condition linked to occupational and recreational behavior includes tuberculosis among health care workers and volunteers who work abroad in high-risk settings. Coccidioidomycosis may occur in desert rock collectors, laboratory technicians, archeologists conducting excavations, construction workers, hikers and campers, and others exposed to desert dust in the endemic area. Histoplasmosis may occur in persons exposed to pigeon or starling roosts, those who clean out old chicken houses with dirt floors, those who cut and clear hollow trees, and those who demolish old buildings or explore caves inhabited by bats. Blastomycosis more often occurs in forestry workers, those who are earth-moving and heavy equipment operators, hunters, and other outdoorsmen. Unlike endemic fungal infections, cryptococcosis has not been strongly linked to occupational and recreational behavior,123 perhaps reflecting the fact that Cryptococcus neoformans is a ubiquitous pathogen that is not geographically restricted. Moreover, good data suggest that a large proportion of the population is exposed to this organism early in life.124 Furthermore, there has been no strong association between exposure to pigeon droppings and development of disease. Other associations include the following: echinococcosis in sheep herders; berylliosis in workers in the aircraft, electronics, and nuclear industries; the pneumoconioses (e.g., silicosis, asbestosis) in sandblasters and shipyard workers; and both chronic and acute pulmonary disease from repeated occupational or environmental exposure to the aerosolized organic antigens associated with extrinsic allergic alveolitis (hypersensitivity pneumonitis)2,40,41 or to irritant gases such as phosgene, ammonia, ozone, and nitrogen dioxide.

Residence and Travel

Because the initial exposure to the microbiologic agents of many chronic or indolent infectious diseases may have occurred months or years before the disease appears, a detailed travel history is essential for any patient with chronic pneumonia. For example, if the patient has lived in the eastern half of the United States, especially the mid-South or upper midwestern regions, chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis and blastomycosis should be considered, because the causative agents are endemic to that area. Likewise, coccidioidomycosis should be a strong consideration in a person with chronic cavitary pneumonia who has lived in or visited an area endemic for Coccidioides immitis/posadasii. Among patients with chronic pneumonia and a history of living in or travel to the U.S. Pacific Northwest or British Columbia, infection due to C. gattii should be considered. Unlike some of the other endemic mycoses, where travel to the endemic area is sufficient to confer risk,69,70 realistically paracoccidioidomycosis should be considered only for patients who have ever lived in Mexico, Central America, or the regions of South America that are endemic for Paracoccidioides brasiliensis.

In the setting of a potentially relevant travel history, in addition to identifying specific regions visited, it is often necessary to explore in detail rural versus urban exposure, the type of lodging, sources of drinking water, exposure to local foods, working environment, and other activities such as swimming and hiking. For example, a person who has lived or traveled extensively in Southeast Asia, particularly in low-lying or rice-growing areas, who manifests chronic pneumonia with pulmonary roentgenographic abnormalities resembling those of tuberculosis or a pulmonary mycosis, may be suffering from melioidosis.125,126 Pulmonary paragonimiasis should be considered in the visitor to Southeastern Asia or the Philippines who consumes raw or partly cooked shellfish and who has chronic pulmonary symptoms plus dense, nodular lung opacities and ring shadows on the chest roentgenogram.127

Contacts, Habits, and Drugs

In the past few decades, most cases of pulmonary tuberculosis in the United States have been diagnosed in homeless persons, alcoholics, older adults, patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and immigrant population groups.128,129 In patients and health care workers in whom tuberculosis is suspected, contacts among companions, relatives, or patients with tuberculosis should be sought. In addition, tuberculosis should be suspected in persons living or working in closed environments such as jails and prisons, homeless shelters, drug rehabilitation centers, and nursing homes. Inquiry should be made into the patient’s smoking and drinking histories and other personal habits. The likelihood of cancer of the lung and some of the invasive mycoses such as aspergillosis and histoplasmosis is greater in a smoker than in a nonsmoker. Aspiration pneumonia, chronic gram-negative bacillary pneumonia, tuberculosis, and pulmonary sporotrichosis are more likely to occur in an alcoholic than in a nondrinker. Intravenous drug users who inject heroin or other illicit agents are at risk for not only infection with HIV and subsequent development of AIDS but also septic pulmonary emboli associated with tricuspid or pulmonic valve infective endocarditis, necrotizing pneumonia, single or multiple lung abscesses, or an interstitial granulomatous reaction to the injected material, resulting in pulmonary hypertension (see Chapter 317). Similarly, frequent use of free-base (crack) cocaine has been reported to cause chronic organizing pneumonia, eosinophilic lung disease, interstitial pneumonitis, and pulmonary hemorrhage or infarction.24,130

More than 100 different pharmaceutical agents have been reported to cause acute and chronic pulmonary symptoms with radiographic abnormalities.15–23,131–133 Early in the course of drug-induced pulmonary disease, the chest radiographic findings may be normal; later, an interstitial, nodular, or alveolar pattern (or a combination of these) may be present. Still later, chest radiography may reveal only a fibrotic pulmonary process. The agents that are most likely to cause chronic pulmonary disease include cytotoxic agents such as bleomycin, busulfan, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, nitrosoureas, noncytotoxic agents such as amiodarone, gold salts, nitrofurantoin, and penicillamine, as well as disease-modifying agents for rheumatologic disease such as etanercept, infliximab, and leflunomide.17–23 Because drug-induced pulmonary disease may develop after drug therapy has been discontinued, the physician should inquire not only about all drugs the patient is presently taking but also about those taken in the recent past.

Questions about recent antimicrobial therapy are critically important. Which antimicrobial(s) was used? Did the therapy result in radiographic or clinical improvement? If not, was the antimicrobial drug used in sufficient quantity and duration to cure the suspected process or alter its course? Was the appropriate agent used? What effect did the antimicrobial agent have on the results of cultures? Does the report of “normal flora” from the sputum culture merely reflect the elimination of a specific pathogen by antimicrobial therapy?

Underlying Disease

Pulmonary complications, including acute and chronic or refractory pneumonia, are especially common in persons with AIDS111–116 and other conditions associated with impaired host immunity, such as high-dose corticosteroid therapy, cytotoxic therapy, hematopoietic stem cell and organ transplantation, Job’s syndrome, and chronic granulomatous disease.134,135 Patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus or preexisting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are at higher risk for development of chronic or persistent bacterial pneumonia. Similarly, chronic obstructive lung disease commonly precedes fibrocavitary histoplasmosis or M. avium complex infection. Structural lung disease, such as preexisting bullae, bronchiectasis, and endobronchial lesions, may also predispose to chronic pneumonia. For example, recurrent or persistent pneumonia in the same area of the lung raises the suspicion of a local endobronchial lesion that may not be apparent on routine chest radiographs. Because aspiration may predispose to chronic pneumonia, inquiry should be made into a history of recent dental problems or manipulation, sinusitis with chronic nasal congestion, disorders of swallowing resulting from neurologic or esophageal disease, seizure disorders, recent anesthesia, quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption, and any illness leading to an unconscious state. Finally, it should be determined whether the chronic pneumonia is most likely community acquired or health care associated.

Clinical Features

Symptoms

There are many causes of chronic pneumonia, and no single symptom complex is common to all causes. Often, nonspecific and constitutional symptoms, including fever, chills, and malaise, are present initially, followed by progressive anorexia and weight loss, indicating chronic illness. Pulmonary symptoms may be present early but frequently appear later in the course of the illness. Any patient with a prolonged illness and nonspecific constitutional complaints plus pulmonary symptoms—including a new or persistent cough, sputum production, hemoptysis, chest pain (especially pleuritic pain), or dyspnea—deserves medical evaluation, including a routine chest radiograph and, when findings on these studies are nonspecific and suggestive of a chronic parenchymal process, a computed tomography (CT) examination of the chest.

Evidence of extrapulmonary involvement should be explored with each patient. For example, chronic pneumonia with skin lesions should suggest coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, or, in the appropriate epidemiologic setting, paracoccidioidomycosis. Similarly, cryptococcosis, nocardiosis, histoplasmosis, penicilliosis, and Kaposi sarcoma should be important considerations for patients with skin lesions and with AIDS or other conditions associated with significant impairment of cell-mediated immune function. Mucous membrane lesions should also raise the possibility of histoplasmosis, paracoccidioidomycosis, penicilliosis, or Kaposi sarcoma. Monoarticular or polyarticular arthritis, polyarthralgia, or localized bone tenderness or pain may indicate systemic vasculitis. A history of chronic pneumonia with persistent headache and abnormal cerebrospinal fluid should raise the suspicion of tuberculosis, cryptococcosis, or coccidioidomycosis involving the lungs and central nervous system (CNS). The presence of focal neurologic signs and symptoms is strong clinical evidence for a space-occupying lesion in the CNS; such findings in a patient with a cavitary infiltrate seen on a chest radiograph suggest the possibility of a brain abscess associated with chronic suppurative lung disease caused by nocardiosis101–103 and microaerophilic or anaerobic bacteria, or both.44,45,46,47 Similarly, the triad of skin nodules, pulmonary nodules, and CNS abnormalities suggests lymphomatoid granulomatosis.7,8,9

Signs

Although the findings on physical examination of the chest are usually not helpful in differentiating specific causes of chronic pneumonia, the presence of generalized wheezing or other signs of bronchospasm, in the absence of underlying lung disease, indicates an asthmatic component to the pulmonary illness and raises the possibility of a disorder causing both pneumonia and asthma, such as extrinsic allergic alveolitis, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, or allergic angiitis and granulomatosis (Churg-Strauss syndrome). Similarly, localized wheezing suggests the presence of an endobronchial obstructing lesion. The findings of tachycardia, cardiomegaly, gallop rhythm, and ankle edema provide evidence of cardiac disease, suggesting that the pulmonary symptoms and signs result at least in part from cardiovascular causes. The presence of skin lesions, clubbing, cyanosis, or phlebitis is not specific for any single pulmonary disorder but may help narrow the differential diagnosis, especially when considered along with other clinical and epidemiologic information. The presence of abnormal liver function, lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, and/or splenomegaly with chronic pneumonia suggests a systemic disorder involving the reticuloendothelial system, such as sarcoidosis, chronic disseminated histoplasmosis, or tuberculosis.

Diagnostic Procedures

Initial Laboratory Studies

Routine laboratory studies can provide important clues to diagnosis. Pancytopenia suggests miliary tuberculosis, disseminated histoplasmosis, or a myelophthisic disorder such as metastatic tumor involving the bone marrow. Isolated anemia is commonly associated with chronic pneumonia but is a nonspecific finding. A normal leukocyte count does not exclude infection. In particular, chronic fungal pneumonia may be associated with a normal or minimally elevated leukocyte count. Leukopenia or lymphopenia should raise the suspicion of an HIV infection. In addition, leukopenia is consistent with a diagnosis of sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, or neoplasia. A leukemoid reaction is nonspecific and may be seen in disseminated mycobacterioses and mycoses. Leukocytosis with polymorphonuclear cell predominance is suggestive of, but not specific for, a bacterial cause including actinomycosis but is also seen in Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Routine laboratory tests that measure the function of other organs may provide more helpful information. Liver function studies, including bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and serum aspartate aminotransferase determinations and prothrombin time, should be performed for most patients. Urinalysis, with particular attention to the urinary sediment, plus tests of renal function including measurement of blood urea nitrogen and creatinine, should also be done. Abnormalities of liver function (especially elevated enzyme levels), kidney function, or both should raise the suspicion of disorders that are not limited to the lung but are known to involve multiple other organs, including the liver and kidney. Such disorders include disseminated histoplasmosis and disseminated mycobacteriosis, as well as the vasculitides, sarcoidosis, and certain neoplastic diseases, especially the lymphoproliferative disorders.

In a patient with an abnormally low serum globulin level, a quantitative serum immunoglobulin determination should be obtained to evaluate for common variable immunodeficiency disorder or other disorders associated with hypogammaglobulinemia. Studies that should be performed in patients with suspected vasculitis include serologic tests for antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (C-ANCAs), C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. In addition, measurement of serum angiotensin-converting enzyme may be useful, although it is a nonspecific test for which levels are increased in patients with a number of granulomatous disorders, including 30% to 80% of patients with sarcoidosis.28,29

Additional Studies

Basic core studies should be performed on all patients with chronic pneumonia, regardless of the suspected cause, but there should be flexibility in choosing additional tests or procedures to confirm a specific diagnosis. The orderly sequence of diagnostic studies described in the following sections necessarily results in oversimplification and consequently overlooks the unique aspects of a given patient’s illness.

Chest Radiographic Studies

The chest radiograph, including posteroanterior and lateral films, is a reasonable screening procedure, but high-resolution CT (HRCT)136 provides invaluable information. Occasionally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful, particularly in the evaluation of the noninfectious causes of chronic pneumonia. Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning (fluorodeoxyglucose PET), which measures metabolism by glucose uptake, has often proved disappointing in distinguishing malignant from infectious lung lesions.137 In Table 72-2, disorders are grouped according to the type of radiologic abnormality that is characteristic of the disease. In some disorders, there is a spectrum of radiologic manifestations, and these disorders appear more than once in the table. Typical radiographic findings may provide clues to specific diagnoses. For example, demonstration of anterior mediastinal involvement argues strongly in favor of neoplasia, including lymphoma, thymoma, and metastatic carcinoma, as the cause of chronic pneumonia syndrome and argues against an infectious cause.

TABLE 72-2

Radiologic Patterns of Diseases: Common Causes of Chronic Pneumonia

| PATTERN OF DISEASE | FEATURES |

| Diseases That Cause Patchy Infiltrates and/or Bronchopneumonia or Lobar Consolidation | |

| Infectious Processes | |

| Aspiration pneumonia secondary to mixed aerobic and anaerobic infection | Usually dependent portions; superior or basilar segments of lower lobes, or posterior segments of upper lobes; pleural involvement with empyema common |

| Necrotizing pneumonia secondary to infection by Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, or Nocardia | Any lobe or segment |

| Actinomycosis | Commonly involves lower lobes; cavitation frequently present; pleural involvement with empyema common, may extend into chest wall |

| Tuberculous exudative pneumonia | Not restricted to upper lobes; often bilateral, with perihilar distribution |

| Blastomycosis | Often, a dense area of lobar or segmental consolidation; calcification and pleural disease infrequent |

| Cryptococcosis | Single or multiple infiltrates, often with sharp border, occasionally cavitary, rarely calcified; pleural effusions in presence of parenchymal disease |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Asymptomatic bilateral fluffy infiltrates; may be extremely indolent and asymptomatic at presentation |

| Noninfectious Processes | |

| Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia | Rapidly progressive, dense infiltrates; usually peripheral (pattern is the reverse of pulmonary edema) |

| Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia | Patchy nonsegmental areas of consolidation, often subpleural and bilateral; large irregular nodules |

| Diseases That Cause Pulmonary Cavitation | |

| Infectious Processes | |

| Pyogenic lung abscess complicating aspiration pneumonia | Usually single cavity; location same as aspiration pneumonia; air-fluid level common |

| Complicating necrotizing pneumonia | May involve any lobe; often multiple and bilateral, depending on route of acquisition of pneumonia |

| Tuberculosis-reactivation or adult type | Usually upper lobes; often bilateral; may be multiple; fibrosis and calcification common |

| Atypical mycobacterial disease | Radiologically indistinguishable from tuberculosis, except that cavitation may be more frequent |

| Melioidosis | May be acute or chronic and involve any lobe |

| Rhodococcal lung disease | Simulates tuberculosis or nocardiosis; cavitation common |

| Histoplasmosis, chronic cavitary | Mimics tuberculosis; upper lobes frequently involved but any lobe can be involved; unilateral or bilateral |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Usually a single, thin-walled cavity with minimal involvement of surrounding lung; occasionally a thick-walled cavity surrounded by extensive parenchymal disease |

| Sporotrichosis | May mimic tuberculosis but can involve any lobe; cavitation is frequent |

| Aspergillosis | Single or multiple areas of pneumonia with or without central cavitation; not to be confused with fungus ball of the lung |

| Paragonimiasis | Cystlike lesions and cavities, usually associated with linear or patchy infiltrates, fibrosis, and/or calcification |

| Echinococcosis | Single or multiple discrete, sharply defined, round lesions (cysts) with little surrounding inflammatory response; cavitation and/or calcification may occur |

| Noninfectious Processes | |

| Wegener’s granulomatosis and lymphomatoid granulomatosis | Often, multiple nodules with cavitation; may be unilateral or bilateral granulomatosis |

| Silicosis | Associated with conglomerate nodular densities, frequently in upper lobes; usually superimposed on background of diffuse nodulation; rarely, eggshell calcification of hilar nodes |

| Bronchogenic carcinoma | Thick-walled cavitation more common in squamous cell type |

| Lymphoma, especially Hodgkin’s disease | Cavitation may occur in peripheral parenchymal nodules |

| Kaposi sarcoma | Small or large nodules associated with peribronchial cuffing and “tram track” opacities |

| Diseases That Cause One or More Dense, Well-Circumscribed Nodules | |

| Dirofilariasis (usually single) | — |

| Histoplasmosis (histoplasmoma) | May have calcification in center or in hilar nodes |

| Coccidioides spp. (coccidioidoma) | May have calcification in center or in hilar nodes |

| Tuberculosis (tuberculoma) | May have calcification in center or in hilar nodes |

| Malignancy | — |

| Infectious and Noninfectious Diseases That Cause Chronic Diffuse Pulmonary Infiltration and Fibrosis | |

| Alveolar Pattern | |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |