Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) was first described in 1864 by Sutton

23 and later recognized and reported by Rendu,

24 Osler,

25 and Weber,

26 and it is thus also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome. It is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by multiple telangiectatic lesions involving the skin and mucous membranes associated with epistaxis and other bleeding complications. HHT has an estimated prevalence of 1 in 8,000,

27 with complete penetrance by 40 years of age.

28Genetic studies have identified several mutations responsible for the vascular malformations. Mutations in the endoglin gene on chromosome 9 (HHT1) or in the activin receptor-like kinase

(

ALK1) gene on chromosome 12 (HHT2) account for ˜85% of the cases. Currently more than 500 mutations in the ALK1 or endoglin genes have been identified, and each family studied appears to have a unique mutation.

27 Endoglin is an integral membrane glycoprotein expressed on endothelial cells in arterioles, venules, and capillaries. This glycoprotein and ALK1 serve as a binding protein for transforming growth factor-

β (TGF-

β).

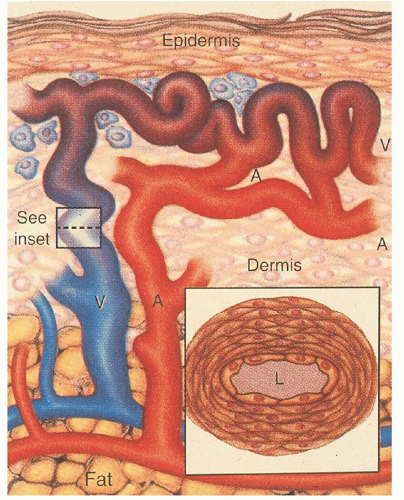

The mechanisms by which these genetic defects result in telangiectatic lesions have not been identified. Ultrastructural analysis of cutaneous HHT lesions suggests that postcapillary venule dilation is the earliest identifiable morphologic abnormality.

32,

33 As the venules enlarge, they become convoluted and interconnect with arterioles through capillary segments. The capillary segments eventually disappear, and direct arteriolar-venular communications are established (

Fig. 50.1). An infiltrate of mononuclear cells appears in the perivascular region of the HHT lesions.

The bleeding manifestations are thought to occur because of mechanical fragility of these vessels. Common abnormalities in the hemostatic system do not seem to represent a major factor in the underlying bleeding tendency. HHT patients manifest a variety of other complications including shunting, emboli, and thrombosis.

Clinical Manifestations

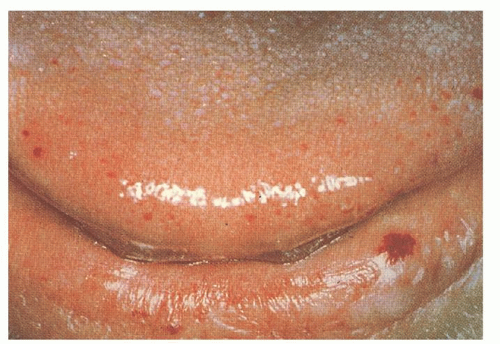

The cutaneous lesions usually appear in affected persons by 40 years of age, and they increase in number with age. The lesions measure 1 to 3 mm in diameter and are sharply demarcated in appearance (

Fig. 50.2). They blanch with pressure, but the blanching may be incomplete as a result of “strangulation” of coiled loops of vessels.

34,

35 The telangiectatic lesions are most commonly found on the face, lips, nares, tongue, nail beds, and hands. Some patients have only a few lesions, necessitating a thorough search in anyone suspected of having HHT. Bleeding from these cutaneous telangiectasias is uncommon and rarely of clinical importance. One report suggests that capillaroscopy of the dorsal hands can detect morphologic changes in the skin microcirculation, including microscopic telangiectatic lesions, but the clinical utility of this is undefined.

36Epistaxis is the presenting complaint in up to 90% of patients with HHT. This symptom results from bleeding telangiectatic lesions over the inferior turbinates and nasal septum. Symptoms usually occur before 35 years of age and are highly variable. Approximately one-third of patients have mild symptoms requiring no treatment, and another third have moderate symptoms requiring only outpatient treatment. The remaining third have severe symptoms often requiring inpatient treatment, transfusions or chronic iron replacement therapy, and surgery.

35 The nosebleeds may become more difficult to control as the patient ages.

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations (PAVMs) occur in 30% of patients with HHT, and 85% to 90% of people with PAVM are found to have HHT.

32,

34,

35,

37 Genetic linkage studies have found that patients with endoglin mutations have significantly higher rates of PAVMs (40%) than HHT patients with other mutations (14%).

38,

39 The PAVMs are primarily located in the lower lung lobes and are multiple. These PAVMs may result in a significant right-to-left shunt, and patients may develop dyspnea, cyanosis, clubbing, fatigue, decreased exercise tolerance, migraine headaches, and polycythemia. Paradoxic emboli can occur and result in brain abscesses, transient ischemic attacks, and strokes. The prevalence of cortical infarcts has been reported to be as high as 14% in patients with a single PAVM and increases to 27% in patients with multiple PAVMs.

40 These lesions may also bleed and result in hemoptysis or hemothorax; pregnant women with PAVMs appear to be at increased risk.

41The detection of PAVMs may be difficult in patients with few or no symptoms. Physical examination may uncover an end-inspiratory bruit.

34 A chest radiograph may detect a coin lesion but often misses smaller lesions. Gravitational shifts in blood flow to the lung bases result in increased right-to-left shunting in the sitting or standing position. Physiologic tests such as measuring O

2 saturation in the supine and standing position (on room air and 100% O

2) can detect the positional change in shunting and can be used to screen patients for PAVMs. However, the best screening test for PAVM appears to be contrast echocardiography.

42 Patients with a positive screening test should undergo an unenhanced spiral computed tomography (CT) to confirm and further characterize the PAVM.

43 Pulmonary angiography is a less sensitive study but is necessary in treatment planning.

Approximately 20% of patients with HHT develop significant upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) tract hemorrhage. Bleeding is rare before the fifth decade of life. Approximately 40% of the bleeding episodes occur from upper GI tract lesions, whereas only 10% occur in the colon, and a full one-half are indeterminate after evaluation.

35 Spontaneous regression of GI bleeding is rare, and steady progression or chronic intermittent bleeding is the norm.

Hepatic involvement occurs in 70% of patients, but symptoms and complications are rare.

44 Patients may have hepatomegaly, a hepatic bruit or thrill, or elevated liver function studies.

45 Types of intrahepatic shunting include hepatic artery to hepatic vein (arteriovenous), hepatic artery to portal vein (arterioportal), and portal vein to hepatic vein (portovenous). These shunts can lead to clinical complications of high-output heart failure, portal hypertension, encephalopathy, biliary ischemia, and nodular regenerative hyperplasia. The dominant type of shunt identified on multiphasic CT does not correlate strongly with the clinical syndrome.

46 Nodular regenerative hyperplasia is found with a 100-fold increased prevalence compared to the general population, and along with portal hypertension can lead to a misdiagnosis of cirrhosis (pseudocirrhosis).

44 It is important to consider this diagnosis in the setting of a liver mass, as biopsy should generally be avoided when suspected. Additionally, if patients with known focal nodular hyperplasia are being treated with estrogen or progesterone therapy, close monitoring is indicated with discontinuation of hormones in the case of symptomatic tumor enlargement.

44 Hepatic AVMs can be detected by dynamic CT,

45 color Doppler ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography (MRI/MRA), or celiac angiography. CT evidence for AVMs includes both the characteristic heterogenous enhancement of the entire liver as well as a dilated common hepatic artery.

46The neurologic manifestations of HHT result from PAVM in up to two-thirds of cases.

32 The remainder of the neurologic symptoms are the result of cerebrovascular telangiectasias, AVMs, aneurysms, and cavernous hemangiomas. Ten to twenty percent of patients with HHT have cerebral AVM, but only 10% of people who have cerebral AVM are found to have HHT.

47 The cerebral

AVMs are often multiple.

47 The annual risk of bleeding from cerebral AVM is low, reported as 0.41% to 0.72%/year (compared to 2% to 4% risk for sporadic, non-HHT AVM).

47,

48 MRI is recommended for detecting these lesions.

41The clinical diagnostic criteria (Curacao criteria) are listed in

Table 50.2.

49 Genetic testing is now available, but requires sequencing the entire coding regions of ALK1 and endoglin, and is complex and expensive.

27 Consultation with a medical geneticist is recommended.

Management

Asymptomatic patients with HHT should be screened with a thorough history, careful physical exam, complete blood count (CBC), and stool guaiac studies. A brain MRI to screen for cerebral AVMs is recommended, and contrast echocardiography to screen for PAVMs should be performed in all patients at least once after the age of 10. Children younger than 10 should be screened with oxygen saturations in the sitting and supine position every 1 to 2 years, with further testing for saturations <97%.

41 Hepatic AVM screening is controversial, but if considered, an ultrasound is the preferred study.

44Recurrent epistaxis can be a perplexing problem, and few trials exist that compare various treatment modalities. Recent efforts to classify the nasal vasculature pattern

50 and develop an epistaxis severity scoring system should pave the way for randomized trials of the various approaches. Prophylactic measures include humidification and saline nose drops. Nasal trauma from vigorous nose blowing, straining, and finger manipulation should be avoided. Antihistamines should also be avoided to prevent drying of the nasal mucosa. Mild bleeding can be treated with absorptive packing and direct pressure. Cautery is commonly used to stop persistent bleeding, but repeated cauterizations can result in necrosis and septal perforation, and should be avoided.

51 Fibrin glue spray was of benefit in a small study.

52 The neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG) laser system has been shown to be effective treatment for epistaxis, and analysis of the vascular pattern appears to correlate with the success rates of laser therapies.

50 Argon plasma coagulation also appears promising, and application of topical estrogens may be useful.

53 Arterial embolization or ligation is effective in some patients. Septal dermoplasty is a technique of removing diseased nasal mucosa and the subepithelial telangiectasias and replacing abnormal tissue with an enduring barrier. In refractory cases, rhinotomy with forehead flap reconstruction may be required.

54 The use of estrogen and e-aminocaproic acid is discussed in the following section.

PAVMs are treated with transcatheter embolotherapy

55,

56 to diminish the risk of paradoxic emboli and other complications. PAVMs with feeder artery diameters >3 mm should be treated. This procedure is effective at decreasing the right-to-left shunt and improving oxygen saturation, and it has a low complication rate. In cases in which embolotherapy is technically difficult, surgical resection should be used. After embolotherapy or surgery, small AVMs may enlarge and become clinically significant. For this reason, patients should undergo screening helical CT scans every 5 years.

32 Because brain abscesses and septic emboli occur in 1% to 20% of patients with HHT and PAVM, these patients should receive prophylactic antibiotic therapy before dental or surgical procedures.

57Bleeding GI vascular malformations can be treated with endoscopic thermal devices including bipolar electrocautery and laser techniques. The mucosa coagulates and sloughs, leaving a small ulcer in the place of the vascular lesion.

58 The ulcer re-epithelializes over the next few days. These treatments are rarely effective for the long term, however, because new lesions continue to develop and small intestinal lesions are not accessible. Estrogen and progesterone have been effective in decreasing the bleeding episodes.

Cerebral AVMs have been treated with surgery, stereotactic radiosurgery, and embolotherapy. A follow-up angiogram should be repeated at 1 year, followed by periodic MRI. Hepatic malformations resulting in high-output heart failure, portal hypertension, or cholangitis should be treated with intensive medical management. Refractory cases have been treated with transcatheter embolization, but the complication rate is significant.

59 The mortality rate of this procedure in HHT has been calculated to be as high as 25% to 40%.

58 Consensus recommendations suggest that the procedure be used only “as a last resort in patients who are not candidates for liver transplant,” and should be absolutely avoided in patients with biliary signs or symptoms.

44 Other treatments that have been successfully used include hepatic artery ligation for localized vascular malformations

59 and liver transplant in patients with extensive lesions.

60

Medical Therapy

Observations in the 1950s that epistaxis decreased during pregnancy and increased after menopause led to the use of estrogens as therapy for HHT. Estrogens in large doses result in metaplasia of the nasal mucosa, resulting in thick layers of squamous epithelium, and electron microscopy studies indicated that estrogen reestablished endothelial cell continuity.

61 A small randomized trial of 3 months’ duration showed no benefit in reducing the number of bleeding episodes with estradiol valerate.

62 However, another author reported 100% success in an uncontrolled series of 67 consecutively treated patients who continued with high-dose estrogen therapy.

61 Several case reports and one small randomized controlled trial evaluated the use of low-dose estrogen-progesterone combination therapy in patients with severe GI bleeding. The bleeding episodes and transfusion requirements significantly diminished in treated patients.

63 Patients on tamoxifen have also been noted in case reports to have decreased episodes of bleeding. Recent reports suggest that either oral or intranasal tranexamic acid may be useful.

64,

65,

66Several intriguing case reports describe regression of telangiectatic lesions and decreased bleeding in patients treated for unrelated reasons with interferon, sirolimus, and bevacizumab,

67,

68,

69 suggesting a possible role for angiogenic inhibitors in managing HHT.

Virtually all patients with HHT have iron deficiency anemia. The treatment of iron deficiency anemia in this setting usually requires more than oral iron replacement. Patients with significant blood loss and anemia who do not respond or do not tolerate maximal doses of oral iron should be given intravenous iron therapy. Three products are recommended for parenteral iron therapy: low-molecular-weight iron dextran, iron gluconate, and iron sucrose.

70 Patients who have toxicity with iron dextran should receive one of the other products. With the currently available options for iron replacement in anemic HHT patients, red cell transfusion should rarely be necessary.

Genetic counseling should be part of the treatment, and referral to a designated HHT center should be considered in most cases. Seventeen U.S. and Canadian HHT centers currently exist and are listed on the HHT Foundation International, Inc. Web site (www.hht.org). Additional centers exist in Europe, South America, Israel, and Asia. A recent review summarizes all aspects of HHT diagnosis and management.

71