(1)

State University of New York at Buffalo Kaleida Health, Buffalo, NY, USA

This operation is performed when there is clinical evidence of involvement of the axillary nodes or microscopically positive sentinel node(s) due to regional metastasis from the primary malignant tumor when the systemic workup shows absence of distant disease. This operation also may be performed for palpable axillary nodes when the axilla is not the regional basin, within the context of complete metastasectomy for a tumor amenable to this approach (e.g., melanoma). Elective node dissection is no longer performed because of the accurate, sensitive and predictive method developed by Donald Morton, intraoperative lymphatic mapping or sentinel node biopsy, which is 98 % accurate in predicting that the other nodes are negative when the sentinel node is negative [1, 2]. If a positive sentinel node is detected with the use of routine staining methods (hematoxylin-eosin) or immunohistochemistry indicating a significant amount of microscopic involvement, the current standard is to perform an axillary node dissection, because in these cases the possibility of microscopic disease in any of the remaining lymph nodes is 15–30 % [3]. For lesser amounts of microscopic involvement of the sentinel node (particularly when microscopic involvement is detected only with the reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR] molecular method), it is not known whether observation or completion lymphadenectomy is the best option. The issue of complete lymphadenectomy in patients with microscopic involvement of the sentinel node is currently the subject of a prospective randomized trial in malignant melanoma.

Operative Technique

Positioning

The patient is positioned supine on the operating table with the arm extended and resting on an arm board. The distal portion of the arm, from the hand to above the elbow, is covered with a sterile stockinette; the proximal arm, axilla, anterior chest wall, posterior shoulder, and supraclavicular area are prepped and draped in the operative field. If the primary site is in the distal arm or hand, then the entire upper extremity and the ipsilateral axilla are prepped and draped in the field [4]. In the past, some practices had the patient supine on the operating table with the arm extended and the forearm flexed at the elbow and fastened over the patient’s head to an ether screen. This position provides relaxation of the pectoralis major and therefore limits the need for assistance to just one person during level III dissection, but paresis of the musculocutaneous nerve resulting in inability of the patient to flex the elbow occurs in about 2 % of patients positioned in this fashion [3, 4]. This complication is probably due to the fact that the forearm is positioned on the ether screen immediately following intubation, when the patient is completely paralyzed; therefore the forearm may be fastened to the screen in an overstretched position that causes paralysis of the musculocutaneous nerve. This paralysis occurred in 3 of the first 200 or so patients in whom we performed axillary node dissection for malignant melanoma. It lasts about 3 weeks, and then the patient recovers full function of this nerve and begins to flex the elbow, but it is an annoying problem that can be avoided by having the forearm and the arm resting on an arm board. Furthermore, keeping the arm free in the field with the skin prepped and draped is also preferable because the primary lesion often is on the arm, so both the primary lesion and the regional nodal basin are included in the draping field. If the primary lesion is near the border of the scapula or on the adjacent upper back, however, one may perform the axillary node dissection and wide excision of the primary site using a lateral position with the affected side up. The procedure may be performed with the patient in a true lateral or semilateral position, or a position of slight elevation of the affected side by the placement of a prop (a folded sheet, 1 l IV bag, or sandbag) under the torso medial to the primary site so that the primary site can be included in the operative field and can be sufficiently visualized for its wide excision.

The Incision

In the past, some authors made the incision for the axillary dissection along the edge of the pectoralis major, but it is then necessary to develop a very wide posterior flap from the border of the pectoralis major to the edge of the latissimus dorsi, while the anterior flap may be very narrow. The potential for ischemia makes the posterior flap more liable to become necrotic. Furthermore, this incision often had to be extended into the arm in order to permit exposure of the axillary vein all the way to the clavicle, with a chance of later scarring and difficulty in abduction of the arm.

A T-shaped incision, a U-shaped incision, and a “lazy S” incision have also been used [4]. The putative advantage of these incisions is that they remain concealed when the arm is in the adducted position, but they would be less likely to allow exposure of level III nodes or exposure of the pectoral muscles when involved by melanoma, compared with the transverse incision described below, which can be extended all the way to the clavicle, if necessary.

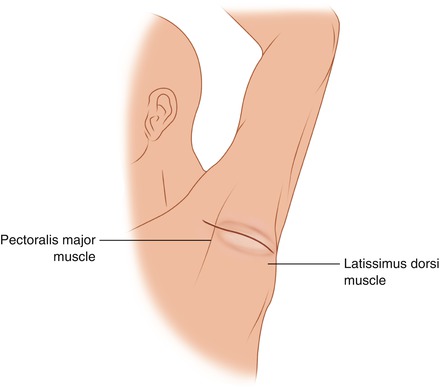

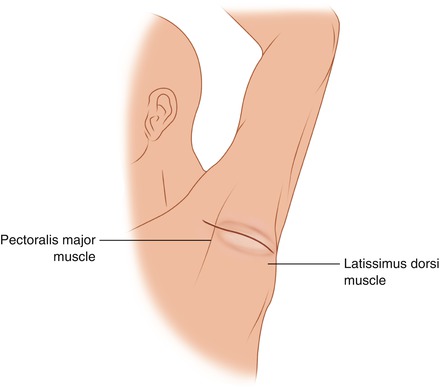

In our experience, the incision of choice is a transverse incision situated about two finger breaths below the axillary crease, and extending from the lateral border of the pectoralis major to that of the latissimus dorsi (Fig. 10.1). This incision is mostly concealed when the arm is adducted, it heals well, possible ischemic effects are equal for both flaps and rare, it is centered over the lymph nodes of the nodal basin, and it provides good exposure for the entire nodal basin, the axillary vein, and the space above and below the vein. Extending the incision medially over the pectoralis major allows the retraction of this muscle and therefore dissection of the lymph nodes up to the apex of the axilla, if this is the intended goal.

Fig. 10.1

A transverse incision extends from medial to the border of the pectoralis major to lateral to the border of the latissimus dorsi, located about two fingerbreadths below the axillary crease

The Dissection

Three levels of lymph nodes are recognized in the axilla: the level I nodes lateral to the pectoralis minor, the level II group behind the pectoralis minor, and the level III nodes above the medial edge of the pectoralis minor to the clavicle. The extent of axillary dissection depends on the type of neoplasm and on whether the operation is being done with a possibly curative intent or is being done mainly for staging purposes, as when other modalities such as chemotherapy and radiation are considered likely to provide equally effective treatment for the particular neoplasm.

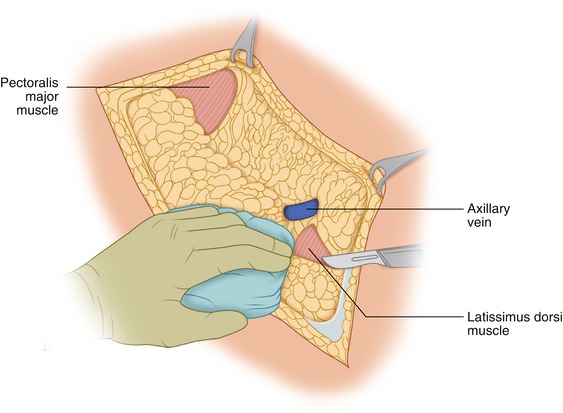

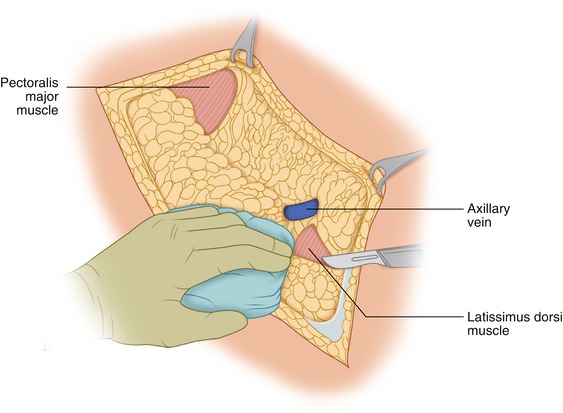

One may start with either the superior or inferior flap. In the drawings, the superior flap is shown first (Fig. 10.2). Medially the superolateral portion of the pectoralis major, laterally the edge of the latissimus dorsi, and in the middle the coracobrachialis muscle and the space superolateral to the axillary vein are exposed. The vein can be safely visualized if one uses a scalpel or light cautery dissection with appropriate traction and countertraction of the tissues. The dissection is carried out superiorly in the middle from the coracobrachialis toward the axillary vein, skimming over the brachial plexus, which is clearly seen within its nerve sheaths, thus mobilizing the fat and nodes above the vein to a level below the vein. The small vessels encountered in the plane being developed between the specimen and the brachial plexus may be ligated with fine sutures or clipped with small hemoclips. Cautery is avoided close to the brachial plexus because the radiating heat stimulates the underlying nerves, causing contraction of the corresponding muscles of the arm. Whether the dissection should be carried to the coracobrachialis and coracoid process to mobilize the supra-axillary fat pad and expose the brachial plexus is a controversial point. Most authors support the view that one should stop at the level of the axillary vein, as extension of the dissection may injure the brachial plexus and also may be unnecessary. We have not had such an injury in over 600 axillary node dissections, however, so it is extremely unlikely if one is careful with the dissection and the patient is not paralyzed by the anesthetics, so that one can feel the reaction of the underlying nerve if the dissection comes close. Extended dissection should not necessarily be done routinely (although in our practice it is), but it is called for if obviously involved lymph nodes overlap the vein and extend to the space above the vein in front of the brachial plexus, and if palpable nodes are located below the vein. In these patients, a complete therapeutic node dissection should include the supra-axillary fat pad and nodes. The presence of involved nodes in this area does not necessarily indicate incurability, and through their dissection one can eliminate all the tumor in the axilla and avoid the consequences of a locally growing tumor in the axilla, which may later ulcerate and cause pressure on the nerves of the brachial plexus, producing severe pain, edema, and rarely gangrene of the extremity that requires an emergency palliative forequarter amputation.

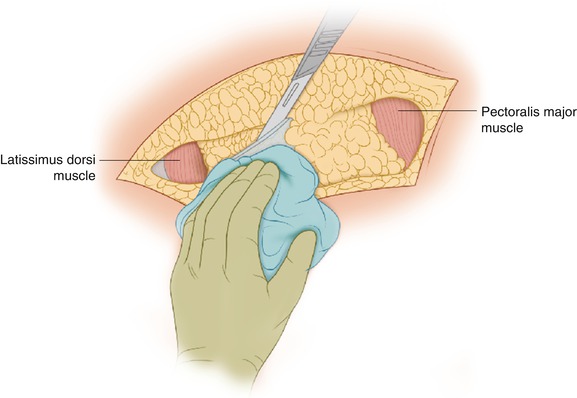

Fig. 10.2

The superior flap is developed to above the lateral border of the coracobrachialis

The inferior flap is developed starting with a thickness of 3–4 mm, as in the superior flap, and is made thicker as one progresses toward the base of the flap (Fig. 10.3). The intention is to reach the lateral chest wall below the level I group of axillary nodes, exposing the serratus anterior muscle in the middle, the pectoralis major anteriorly, and the latissimus dorsi posteriorly at a more inferior level than the exposure of the latter two muscles when the superior flap was developed. There is no risk of injury of the long thoracic nerve as one dissects to the surface of the serratus anterior because this plane of dissection is well below the point where the nerve enters the superior border of this muscle.