Duane R. Hospenthal

Agents of Mycetoma

Mycetoma is a chronic progressive granulomatous infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue most often affecting the lower extremities, typically a single foot. The disease is unique from other cutaneous or subcutaneous diseases in its triad of localized swelling, underlying sinus tracts, and production of grains or granules (composed of aggregations of the causative organism) within the sinus tracts. These infections may be caused by fungi and termed eumycotic mycetoma or eumycetoma, or by filamentous higher bacteria and termed actinomycotic mycetoma or actinomycetoma. The term mycetoma can also be found in the literature incorrectly referring to a fungus ball found in a preexisting cavity in the lung or within a paranasal sinus, most often caused by Aspergillus spp. Grain formation by infecting organisms is restricted to the diseases mycetoma, actinomycosis (see Chapter 256), and botryomycosis. Actinomycosis is a disease produced by the anaerobic and microaerophilic higher bacteria that normally colonize the mouth and gastrointestinal and urogenital tracts. The portal of entry in actinomycosis is from those colonized sites, whereas in mycetoma the portal is the skin and subcutaneous tissue into which the organism was inoculated by minor trauma. Botryomycosis is a chronic bacterial infection of soft tissues in which the causative organism, often Staphylococcus aureus, is found in loose clusters among the pus.1 In a rare form of ringworm called dermatophyte mycetoma, there are also loosely compacted clusters of hyphae in subcutaneous pus.2 In contrast, mycetoma grains are dense clusters of organisms.

Etiologic Agents

The agents of mycetoma are fungi and aerobic filamentous bacteria that have been found on plants and in the soil.3 The predominance of bacterial versus fungal causes of mycetoma varies among geographic location. Eumycotic (true fungal) disease is caused by a variety of fungal organisms. These can be divided into those that form dark grains and those that form pale or white grains (Table 263-1). Color distinctions are made by observing unstained specimens. Among the fungi causing dark-grained mycetoma, the most common are Madurella mycetomatis, Leptosphaeria senegalensis, and Madurella grisea. Other agents include Corynespora cassicola, Curvularia geniculata, Curvularia lunata, Exophiala jeanselmei, Exophiala oligosperma, Leptosphaeria tompkinsii, Madurella fahalii, Madurella pseudomycetomatis, Madurella tropicana, Phialophora verrucosa, Plenodomas avramii, Pseudochaetosphaeronema larense, Rhinocladiella atrovirens, Pyrenochaeta mackinnonii, and Pyrenochaeta romeroi. Pseudallescheria boydii is the most common cause of pale-colored grains. Other fungi in that category include Acremonium falciforme, Acremonium kiliense, Acremonium recifei, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus hollandicus, Aspergillus nidulans, Cylindrocarpon cyanescens, Cylindrocarpon destructans, Diaporthe phaseolorum, Fusarium solani, Fusarium moniliforme, Neotestudina rosatii, Phaeoacremonium spp., Pleurostomophora ochracea, and Polycytella hominis.4–10 Actinomycetoma is caused by members of the order Actinomycetales, most commonly Nocardia brasiliensis, Actinomadura madurae, Streptomyces somaliensis, and Actinomadura pelletieri. Cases have been reported that were caused by Actinomadura latina, Nocardia farcinica, Nocardia harenae, Nocardia otitidiscaviarum (caviae), Nocardia mexicana, Nocardia transvalensis, Nocardia veterana, Nocardia yamanashiensis, and Nocardiopsis dassonvillei.11–14 Some reports use species names that are not currently recognized, leaving in doubt the identification.15 Actinomycetoma grains are typically white or pale yellow, except those caused by Actinomadura pelletieri, which are red to pink.

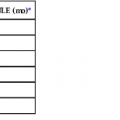

TABLE 263-1

Typical Morphologic Features of Mycetoma Grains

| GRAIN COLOR | CAUSATIVE AGENT |

| Eumycetoma (Eumycotic Mycetoma)* | |

| Black grains | Madurella spp., Leptosphaeria spp., Curvularia spp., Exophiala spp., Phaeoacremonium spp., Phialophora verrucosa, Pyrenochaeta mackinnonii, Pyrenochaeta romeroi |

| Pale grains (white to yellow) | Pseudallescheria boydii, Acremonium spp., Aspergillus spp., Diaporthe phaseolorum, Fusarium spp., Neotestudina rosatii, Pleurostomophora ochracea |

| Actinomycetoma (Actinomycotic Mycetoma)† | |

| Pale grains (white to yellow) | Actinomadura madurae, Nocardia spp. |

| Yellow to brown grains | Streptomyces spp. |

| Red to pink grains | Actinomadura pelletieri |

* 2- to 5-µm diameter hyphae are observed within grain.

† 0.5- to 1-µm diameter filaments are observed within grain.

Epidemiology

The oldest description of this disease appears to date back to the ancient Indian Sanskrit text Atharva Veda, in which reference is made to pada valmikam, translated to mean “anthill foot.”4 More modern descriptions from Madras, India, in the 19th century led to this disease initially being called “madura foot,” or maduromycosis, a term still used by some today to describe eumycotic mycetoma. Mycetoma is most commonly found in tropical and subtropical climates, with the highest incidence reported from endemic areas in the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, Africa, and Central and South America. One of the largest current groups of cases is in Sudan. Only scattered reports describe cases originating in the United States, Europe, and Japan. Disease occurs around five times more frequently in males, commonly in the 20- to 40-year-old age range. Disease is more common in agricultural workers and outdoor laborers but is not exclusively seen in rural areas. Disease occurs sporadically throughout most areas of the world, and some postulate that the increased numbers in tropical regions may also result in part from less use of protective clothing, chiefly shoes, in the warmer, poorer endemic regions.

The causative agents of mycetoma vary from region to region and with climate. Worldwide, M. mycetomatis is the most common cause of this disease, but A. madurae, M. mycetomatis, and S. somaliensis are more commonly reported from drier regions, whereas P. boydii, Nocardia spp., and A. pelletieri are more common in those areas with higher annual rainfall. In India, Nocardia spp. and M. grisea are the most common causes of mycetoma; in the Middle East, M. mycetomatis and S. somaliensis; in West Africa, L. senegalensis; and in East Africa, M. mycetomatis and S. somaliensis. In Central and South America, M. grisea and Nocardia spp. are the common causes of mycetoma, and in the United States, P. boydii is the most commonly recovered causative agent.16

Pathology and Pathogenesis

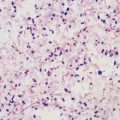

Infection follows inoculation of organisms, frequently through thorn punctures, wood splinters, or preexisting abrasions or trauma. After inoculation, these normally nonpathogenic organisms grow and survive through the production of grains (also called granules or sclerotia), structures composed of masses of mycelial fungi or bacterial filaments and a matrix component. The matrix material has been shown to be host derived with some pathogens. In eumycetoma, hyphal elements often have thickened cell walls toward the periphery of grains, potentially conferring protection against the host immune system.17 Grains are seen in histopathology within abscesses containing polymorphonuclear cells. Complement-dependent chemotaxis of polymorphonuclear leukocytes has been shown to be induced by both fungal (M. mycetomatis and P. boydii) and actinomycotic (S. somaliensis) antigens in vitro.18 Cells of the innate immune system attempt to engulf and inactivate these organisms, but in disease they ultimately fail to accomplish this goal. Abscesses containing grains are seen in association with granulomatous inflammation and fibrosis. Three types of immune responses have been described in response to the grains of mycetoma.19 The type 1 response is seen as neutrophils degranulate and adhere to the grain surface, leading to gradual disintegration of the grain. Type 2 response is characterized by the disappearance of neutrophils and arrival of macrophages to clear grains and neutrophil debris. Type 3 response is marked by the formation of epithelioid granuloma. This host response does not appear to be able to control infection but likely accounts for the partial spontaneous healing that is seen in the disease.

It is not clear whether persons who develop mycetoma have predisposing immune deficits. Disease does not appear to be more common in immunocompromised hosts, and early studies of immune function in persons with mycetoma have not clearly documented a common deficit.20,21 Recent work examining genes responsible for innate immune functions has identified polymorphisms that appear to predispose people to this infection, which may be linked with neutrophil function.22 It has been suggested that the greater frequency of disease in men is not completely explained by increased frequency of exposure to soil and plant material. Progesterone has been shown in vitro to inhibit the growth of M. mycetomatis, P. romeroi, and N. brasiliensis.23,24 In the study of N. brasiliensis, estradiol limited disease produced in animals.23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree