For most women, a diagnosis of gynecologic cancer is a crisis, and it is essential to consider a patient’s psychological and behavioral responses when managing her disease. While most patients adapt and recover, cancer becomes a chronic stressor for some, either because the disease has disseminated and can be controlled only with radical treatment, or because a survivor’s coping strategies are not adequate. This chapter reviews the data on these issues, and presents practical information that can be used to understand patients’ responses and assist patients in coping during diagnosis, treatment, follow-up, and monitoring.

The stress of cancer diagnosis and treatment can have wide-ranging, long-term impacts on patients’ mental health at every stage of the cancer experience. Cancer-specific stress triggers significant biologic effects. For example, following surgery and prior to adjuvant treatment, stress among breast cancer patients was associated with immune downregulation, shown across assays for NK cell cytotoxicity (NKCC), the response of NK cells to recombinant interferon gamma (rIFN-g), and T-cell responses, including proliferative responses to concanavalin A (ConA), phytohemagglutinin (PHA), and a T3 monoclonal antibody (MoAb) (1). Attendance to a patient’s psychological distress may have important benefits beyond alleviating the psychological impacts. Evidence suggests that psychological interventions can improve biobehavioral outcomes and potentially the disease course (2).

Gynecologic Screening and Follow-Up

Research suggests that individuals become distressed during medical screening, long before a cancer diagnosis is suggested (3). In the case of an abnormal screen, many women will experience significant anxiety, distress, and daily life disruptions. Ideström et al. described reactions to abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) test results in a sample of 242 women. More than half of the women surveyed (59%) reported feelings of worry and anxiety after being informed of their abnormal Pap result, and about a third (30%) of women reported that their daily life was disrupted in the time between the initial Pap result and follow-up tests (4). A smaller proportion of women (8%) reported symptoms of sexual dysfunction.

Another large survey of 3,500 women found increased risk for anxiety in response to an abnormal Pap result in women who were younger, had children, were current smokers, or had the highest levels of physical activity (5). Lerman et al. (6) reported that women who received abnormal Pap results worried more about cancer and had significantly more disruptions in mood, daily activities, sexual interest, and sleep patterns when compared to women who received normal results.

With respect to the initial gynecologic oncology consultation, patients have reported significantly elevated psychiatric symptoms, with 42% reporting clinical levels of depressive symptoms and 30% reporting moderate to severe anxiety symptoms, regardless of whether the eventual diagnosis was one of cancer or benign gynecologic disease (7). In a study of women undergoing ovarian cancer screening, most patients who received false-positive results showed little long-term psychological effect other than an increase in worry about cancer, but certain women, including those who underwent a surgical intervention, experienced more significant psychological distress (8).

The relationship between increased psychological distress and nonadherence to screening and treatment recommendations is well documented in cancer patients. Possible explanations for noncompliance following an abnormal Pap result include fear of the diagnostic procedures, not wanting to know if something is wrong, fear of a cancer diagnosis, belief that the outcomes will be negative (fatalism), and belief that one is too old for treatment (9).

While screening for ovarian cancer is under continued investigation, the high mortality associated with the disease has led to the adoption of prophylactic oophorectomy as an effective reducer of risk for women with a hereditary risk. This preventative treatment can have many psychological impacts. Although two studies of women receiving a prophylactic oophorectomy have reported that most (86%) participants were satisfied with their decision to undergo the procedure and experienced a reduction in cancer-related anxiety and worry (10,11), another found that such women experienced levels of cancer-related worry similar to those undergoing screening programs (12). All three studies reported that women who underwent the procedure experienced menopausal symptoms and sexual dysfunction (10–12).

Diagnosis

Stress and its negative impact on quality of life begin with diagnosis (13–15). Risk of suicide for women diagnosed with gynecologic cancer is highest during this time, particularly among women with ovarian cancer, and those for whom surgery is not recommended (16). The term existential plight has been used to describe this period, and the emotional turmoil that continues during treatment (17).

Emotions and sources of distress experienced at diagnosis are diverse. They may include the following:

1. Depression, from life disruption and doubts concerning the future.

2. Anxiety, from anticipating cancer treatment and side effects.

3. Confusion, from dealing with a complex medical environment.

4. Anger, from the loss of childbearing capacity and the opportunity to choose whether to have children.

5. Guilt, from concerns that previous sexual activity may have “caused” the cancer.

An early study conducted in 1989 compared mood disturbance among those recently diagnosed with a gynecologic cancer with two matched groups, one with benign gynecologic disease anticipating surgery, and the other with no disease (i.e., healthy women). All participants completed a self-report inventory on the emotions they experienced during their initial evaluation (18). While both groups with disease reported high anxiety and equivalent levels of fatigue and anger, only women with cancer reported high levels of confusion and described themselves as having negative moods suggestive of depression. A similar study conducted in 2011 by Posluszny et al. (15) reported that women with cancer reported higher levels of traumatic stress and perceived threat than matched controls with benign disease.

Data consistently underscore the significant distress experienced by many cancer patients. Mental health disorders among cancer patients are prevalent, largely unrecognized, and usually untreated. It is consistently estimated that 30–50% of cancer patients meet criteria for mood or anxiety disorders, with depressive disorders (major depression, minor depression, adjustment disorder with depressed mood) being the most common (19,20). Specifically, estimates for major depressive disorder (MDD) are 22–29% for patients with early-stage disease (21), 8–40% for patients with advanced disease (22), and higher for patients with recurrence (23). Among breast and gynecologic cancer patients, Zabora et al. (24) found prevalence of MDD to be 33% and 30%, respectively.

Common comorbidities with depression include anxiety (25,26), poorer quality of life (26–28), fatigue (29,30), and more distress from physical symptoms (31). Unfortunately, cancer patients with depression are often not identified, despite the availability of simple screening measures (32). For example, among 112 women with major depression undergoing cancer treatment, Ell et al. found that only 12% were receiving antidepressants, and only 5% were receiving psychological therapy (33).

Patients experiencing high levels of distress have many difficulties including (i) understanding and remembering all that they have been told, including both simple information (e.g., what time they are to be admitted) and more complex information (e.g., the organs to be surgically removed and the nature of the side effects); (ii) managing personal affairs (e.g., contacting their insurance company or arranging for child care during recovery); and (iii) being a “patient” and allowing others to care for them.

Even for those with some knowledge of gynecologic surgeries, cancer treatment is qualitatively different. For example, a woman’s mother, sister, or a close friend may have related her experiences with hysterectomy. Even if the friend’s surgery involved an abdominal rather than a vaginal approach, the preoperative and postoperative experience for the woman with cancer will be notably different (e.g., bowel preparation, length of recovery, vaginal shortening, bladder dysfunction) and more distress will likely result. It is normal for any patient to experience cognitive, emotional, and behavioral difficulties; and it is the rare patient who does not require supportive assistance as treatment approaches.

The acute stress associated with a cancer diagnosis may portend later difficulties. When there is an absence of positive coping, patients subsequently report a loss of meaning in their lives (34). Patients with high levels of diagnostic distress have been found to have high depressive symptoms during follow-up and lower quality of life (35).

Cancer Treatments

Despite efforts to allay concerns and provide accurate information about treatment plans, many women have misconceptions about their treatments and anxiety often remains high as patients approach surgery, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy. Many of these concerns are similar across treatment modalities, but others are unique to a particular treatment type. For example, bladder irritation and vaginal stenosis may occur with radiation treatment. Lymphedema, on the other hand, may occur with surgery or radiation. Women experiencing lymphedema report lower quality of life, more cancer worry, more problems with sleep, and more physical and social limitations (36).

Whichever treatment modality is utilized, it is important to consider the cultural implications of treatment effects. In a series of focus groups of women diagnosed with cervical cancer, for example, Latina, African American, Asian, and Caucasian women felt differently regarding their control over their illness, particularly in the assignment of blame (37). Latinas often blamed themselves for their diagnosis, seeing cancer as a form of punishment for some failure, while Caucasian, African American, and Asian women often considered their partners as at least partially to blame. Latina and Asian women also worried about the loss of their purpose as a woman with the loss of their fertility. These culturally related beliefs might affect a woman’s treatment seeking, adherence to treatment, and psychological response following treatment.

Surgery

In 1982, Gottesman and Lewis (38) noted greater and more lasting feelings of crisis and a stronger sense of helplessness among patients with cancer, compared to patients receiving surgery for benign conditions. These feelings lasted for as long as 2 months after discharge from hospital. Similar findings have been observed in other studies subsequently. For example, women with advanced cancer have been reported to experience high levels of traumatic stress when compared to those receiving surgery for a benign gynecologic disease (15). Such psychological distress tends to be worse for those with less social support (14).

In addition to stress and anxiety, gynecologic cancer surgery imposes unique burdens. Women of childbearing age who are nulliparous or have not yet achieved their desired family size may become distraught if they lose their childbearing capability (39,40). Because the age of childbearing among women in the United States has risen, the likelihood of this situation occurring has increased. Identifying referral sources for information or fertility-preserving resources may prove difficult for those not near cities or major medical centers (39). Women receiving information about reproductive assistance options experience less distress and depression (41).

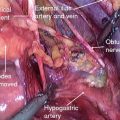

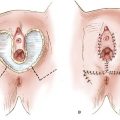

Radical surgery, such as pelvic exenteration, resulting in genital disfigurement or dramatic changes to the pelvis, may produce depression, feelings of isolation, and body image distress (42,43). Other surgeries, such as radical hysterectomy, may produce other effects, such as vaginal shortening and bladder dysfunction. Premature menopause from oophorectomy or ovarian failure may lead to distressing sexual and menopausal symptoms (e.g., atrophic vaginitis, hot flashes). Taken together, bodily changes and the loss of control of bodily functions contribute to decreased quality of life, depression, impaired body image, and anxiety (44). If feasible, less invasive surgeries, such as nerve sparing radical hysterectomy, may mitigate these side effects (44,45).

Radiation Therapy

Most patients report confusion and negative emotions regarding radiation treatments. Misinformation is common, with some patients fearing permanent contamination of themselves or others from treatment, while other patients assume that radiation attacks only “bad” cells, leaving others unaffected. A patient’s prior knowledge of radiation therapy may be based on the experiences of a friend or relative, and if their treatment was unsuccessful or difficult, she may enter treatment believing it will be the same for her (46).

External beam therapy brings fears or uneasiness about the size or the safety of treatment machines and, often, distress from being in a radiation therapy department where there are other patients in obvious ill health. For some women, disrobing and exposing the pelvic area is a daily embarrassment, and field-marking tattoos are visible reminders of the cancer. In one study, roughly 80% of patients expressed an unwillingness to discuss these concerns with their physicians (47). This occurs particularly when patients perceive their physicians as disinterested, embarrassed, or too busy. Patients may also feel they cannot ask “intelligent” questions of their physicians.

As the treatment progresses, the daily procedures of radiation therapy become routine, and many patients report less emotional distress. However, side effects of fatigue, diarrhea, and anorexia then begin. Side effects complicate living, requiring activity reductions and dietary modifications. Previously symptom-free patients may begin to feel and think of themselves as “ill” doubting their positive prognosis. Premenopausal women experience hot flashes, a salient and distressing reminder of their loss of fertility.

At the termination of treatment, these patients might be expected to report a drop in anxiety and fear. Instead, gynecologic patients (48) and other patients with cancer (49) report a differing patterns of anxiety responses. Women with high pretreatment anxiety are less anxious on the last treatment day than on the first, although they remain the most distressed. Those with moderate levels of pretreatment distress report little diminution in distress by the last treatment, and surprisingly, those with low levels of anxiety at the onset of treatment report significantly greater anxiety on the last treatment day. Physical symptoms of fatigue, abdominal pain, anorexia, diarrhea, and skin irritation are peaking at this time. Patients may anticipate that treatment being over will bring a rapid end to symptoms, not knowing that symptoms only diminish with passing months (48).

In contrast to external beam, few patients are familiar with intracavitary radiotherapy. While the replacement of low-dose rate brachytherapy with high-dose rate equipment in most Western countries has reduced isolation times, intracavitary radiotherapy still presents unique challenges to patients. During treatment, women have significant physical discomfort, even when there has been liberal analgesic medication (49). Gas pains, burning sensations, and lower backache are typical, and emotional distress can be pervasive. Visitation restrictions limit contact with family and friends, which may be frightening to a patient if it is perceived as isolation from nurses or physicians. It is not surprising that many women are irritable and upset during the treatment.

If a second radiation application is received, physicians may anticipate that this might be an easier experience for patients, but it is not. Women report feeling more anxious during the treatment, and are naturally more debilitated afterward. Even women with lower levels of anxiety before their first intracavitary treatment are reported to experience elevated levels of anxiety after their second application (50).

Without assistance, recovery from the physical and psychological distress of radiation therapy is slow. Nail et al. have documented an incidence of nausea in 5%, anorexia in 15%, diarrhea in 15%, and fatigue in 32% of gynecologic patients as long as 3 months after treatment (51). Complications, such as radiation proctitis or vaginal atrophy emerge across time. While some physical symptoms and quality of life may improve beyond levels seen before treatment by 3 to 4 months, anxiety, depression, and some physical symptoms may persist (52,53).

Sexual dysfunction after radiotherapy is common, severe, and persistent. Decreased lubrication and vaginal tenderness or pain are significant sexual disruptors during recovery, with lack of sexual interest and dyspareunia being major problems for many women. Alterations to the vaginal anatomy, including vaginal shortening and stenosis, begin during radiation treatment (54). Longitudinal data show that sexual dysfunction persists at least 2 years after radiotherapy treatment as the vaginal changes continue, with approximately 85% of women reporting low or no sexual interest and 55% experiencing mild to severe dyspareunia (55).

Any patient receiving radiation is at risk for dyspareunia. It is most severe among women receiving both external and intracavitary radiation, although external beam alone also produces dyspareunia (18). The magnitude of pain during intercourse appears to decrease during the months after treatment for women who maintain sexual activity. Atrophic vaginitis is extremely difficult to treat, making a regimen of vaginal care essential for all patients. Ovarian failure worsens these difficulties.

Chemotherapy

Patients’ reactions to learning that they need chemotherapy can range from extreme negativity (i.e., feeling nervous, anxious, or depressed) to relief that some kind of treatment is available to them. This mix of emotions reflects distress at having to undergo a difficult treatment, which many believe is only for “hopeless” cancers, and the fear that it will not control the disease. In one study, nearly 60% of women at their first chemotherapy session reported levels of distress high enough to warrant follow-up by an oncologic psychologist (56). To allay patients’ concerns, medical personnel usually provide descriptions of, and written materials about, the effects and side effects of treatment. In spite of this, as many as 10% of patients report uncertainty and lack of knowledge when beginning treatment (57). Others may approach chemotherapy optimistically and believe that they will belong to the small subset of people who do not experience any side effects.

Patients experience significant distress throughout chemotherapy that declines slowly with time. As treatment occupies more and more of a patient’s life, worries become intrusive, and the intense and noxious side effects generate a clear awareness of illness. Compared to active, positive coping (e.g., seeking information, asking for social support), negative coping (e.g., avoiding information, withdrawal, substance use) is predictive of distress and more frequent reports of physical symptoms (58,59). In addition, women who attempt to control the side effects and fail become more distressed than those who report that they have coped successfully (57).

Anticipatory nausea and vomiting may complicate the course of chemotherapy for approximately 10% of patients (60,61). This refers to nausea and vomiting before the administration of chemotherapy. In most cases this is a conditioned response, resulting from the pairing of the stimuli surrounding the administration of chemotherapy (e.g., needles, smell of alcohol, the clinic) with the occurrence of posttreatment nausea and vomiting. With repeated cycles, the stimuli become conditioned and thus are able to evoke nausea or vomiting before the chemotherapy is administered. Once anticipatory reactions develop, they can become more general (e.g., alcohol-containing substances such as perfume may cause nausea), and they occur progressively earlier (e.g., on entering the hospital, rather than on entering the treatment room).

Factors that place a patient at risk for development of anticipatory nausea and vomiting include (62,63) the following:

• Age less than 50 years

• Lengthy infusion and toxicity of the regimen

• Severe posttreatment nausea or vomiting that is not controlled in the early cycles

• Extreme anxiety and/or depression

• Previous susceptibility to nausea and/or motion sickness

Women with higher levels of state anxiety tend to be more susceptible to both anticipatory and posttreatment nausea and vomiting (64). The likelihood of anticipatory nausea and vomiting developing has been reduced with prechemotherapy administration of antiemetics, and the use of second- and third-generation agents with lower gastrointestinal toxicities.

Confusion and cognitive impairment, colloquially referred to as “chemobrain,” are prevalent in patients receiving chemotherapy and are distressing symptoms for the patient and her family. In a study of ovarian cancer patients, 69% reported some level of cognitive impairment (65). Pharmacologic effects of chemotherapeutic agents account for some cognitive changes (66), and such changes further emphasize the illness and its consequences to the patient.

Early Posttreatment

Patients often receive little preparation for the unique challenges of concluding active treatment (67). While it is certainly the case that patients are relieved that treatment is over, this is a transition. Daily or weekly contacts with treating physicians and nurses abruptly end, and with it the familiarity of context and support that was a part of being in treatment. Recovery from radiation therapy and chemotherapy is slow. While symptoms may diminish within weeks, residual fatigue will last upward of 12 months.

Reestablishing new routines with family, friends, employment, and so on, begins, and not all the transitions may be smooth. Some individuals may have “powered through” the diagnosis, treatments, and recovery without emotionally processing the cancer experience. This experience is captured in the common sentiment after treatment, “then it hit me . . . .” Taken together, experiences such as these continue up to 2 years following the end of treatment before emotions and general adjustment stabilize. In the general case, physical and psychological symptoms and quality of life improve (15,68–71), but some symptoms may persist. Sleep disturbances, sexual dysfunction, anxiety, and body image concerns have all been found to persist for even a year or longer (68,71–77). Younger patients may have a particularly difficult time during this transition (68,70,78).

Survivor Years

The permanent sequelae of gynecologic cancer treatment, while expected, demand new behaviors and coping strategies from survivors. Data indicate that most patients cope successfully; many report renewed vigor in their approach to life, stronger interpersonal relationships, and a “survivor” adaptation (79–81). Patients report that physical sequelae pose the most significant survivorship challenge (82). Although psychological distress declines for the majority (70%), approximately 25% of patients experience significant residual anxiety-related or depressive symptoms (74–76,82,83). In short, physical sequelae and psychological adjustment are not necessarily mitigated by the passage of time (73,83–85). Physical and psychological sequelae covary such that worse psychological outcomes are associated with worse physiologic outcomes and worse quality of life (73,81,83–85), although younger women are at risk for worse psychological and quality-of-life outcomes despite their better physical functioning (81).

Physical side effects of treatment vary by treatment modality, even many years after treatment (73). Survivors’ general health-related quality of life is often reported to be comparable with healthy controls, controls with minor medical illness, and standard norms (70,81,85,86). Long-term survivors’ disease-specific quality of life, however, has been found to be comparable to scores found shortly after cancer treatment (85). In one study, long-term survivors (average 17 years) reported significantly worse physical health and physical functioning than matched controls without a history of cancer. This suggests that the physical difficulties of survivors may be obscured by more general measures.

Rates of psychiatric disorders—primarily mood or anxiety disorders—are substantial (72,74–76,82,83,85–87). Fear of death or recurrence may contribute for those who have a precancer generalized anxiety disorder. Such fears are common and may persist (81,86). Such reactions are substantial in gynecologic cancer survivors, with traumatic stress symptoms reported in 13–19% (74,88). They may be more common for those undergoing more difficult treatment regimens or those receiving life-altering and/or disfiguring cancer treatments (e.g., pelvic exenteration).

Patients with a prior history of psychiatric treatment and/or traumatic stress have reported greater symptom rates, as have patients who have reported greater rates of unmet supportive care needs (30,74). Although symptom rates were high, only one study has investigated clinically diagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and it found no clinical cases among 75 women screened for PTSD and followed for 1 month (88). Thus, while it is essential to be attentive to traumatic stress symptoms in gynecologic cancer survivors, depression and anxiety are more prevalent.

Recurrence and Progressive Disease

Compared to earlier phases of gynecologic cancer, information about the psychological impact of recurrent cancer is scarce. In one controlled, prospective study of 227 women followed for 8 years after their diagnosis of breast cancer, 30 were diagnosed with recurrence (89). Women’s reports of cancer-specific stress at recurrence were equivalent to their reports after their initial diagnoses. Emotional distress, social functioning, and quality of life showed no disruption at recurrence, and were equivalent to that of controls that had not recurred. This suggests that while a recurrent diagnosis is still exceedingly stressful, women may be more resilient at a recurrent diagnosis than they were at their initial diagnosis. Another study reported that such women may also experience less confusion than women receiving their initial diagnoses (90).

This is not to suggest, however, that women with recurrent gynecologic cancer do not experience emotional difficulties, particularly when their disease progresses. In a sample of ovarian cancer patients nearing the end of life, Roberts et al. found that 39% exhibited acute fears, the most common being fear of abandonment (32%) and isolation (17%) (91). In a study of 217 women with ovarian cancer followed during their last year of life, Price et al. found that quality of life declined sharply in the final 6 months, while symptoms such as nausea, anorexia, and pain increased (92). A cross-sectional study of 60 women with recurrent ovarian cancer suggested that younger age, greater symptom distress, and fewer years in their current relationship were related to worse adjustment to illness (93).

End-of-life care is essential. In a sobering review of the literature, however, Lopez-Acevedo et al. (94) reported that hospice care was underutilized, and used ineffectively when it was utilized, for gynecologic cancer patients. Although palliative care may reduce healthcare utilization while improving physical and psychological symptoms, women are often referred too late to fully benefit (94).

Addressing the Psychological Impacts of Cancer

The psychological and behavioral aspects of gynecologic cancer can be addressed in a number of ways. Some anxiety and confusion can be mitigated or prevented simply through the provision of information, while depression or generalized anxiety may require more intensive therapy. Data on the effectiveness of various interventions addressing the psychological needs of gynecologic cancer patients are described below.

Identifying Patients with Symptoms of Anxiety or Depression

Guidelines suggest that all patients should be screened for distress at their initial visit, at appropriate intervals as clinically indicated, with significant changes such as the diagnosis of recurrence, and when the transition to palliative and end-of-life care is made (95). Valid and reliable measures are available such as the Patient Health Questionnaire Nine-Symptom Depression Scale (PHQ-9) (96) for depressive symptoms, or the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7 (97) scale for anxiety symptoms. Measures such as these generate scores with established cut-offs that are clinically meaningful. Whatever strategy is used for screening, it is important that a phased assessment be used that does not rely simply on a symptom count. As a first step for all patients, identification of risk factors for distress is important.

Patients most vulnerable to significant symptoms of anxiety or depression include those with following (95):

• Prior mood or anxiety disorder, with or without prior treatment

• Familial history of depression, with or without prior treatment

• Familial history of anxiety disorders, with or without prior treatment

• Other psychiatric disorders, including substance abuse

• Recurrent, advanced, or progressive disease

• Presence of significant chronic illness(es) in addition to cancer

• Singleton (single not married, widowed, divorced) versus partnered

• Unemployed or lower socioeconomic status

As a second step, a measure such as the PHQ-9 can be used to assess for the classic depressive symptoms of low mood and anhedonia, and if endorsed, other depressive symptoms can be assessed (98). Many individuals (50–60%) with a diagnosed depressive disorder will have a comorbid anxiety disorder, with generalized anxiety being the most prevalent (99). It has been recommended that patients be assessed for generalized anxiety disorder, as it is the most prevalent anxiety disorder, and is commonly comorbid with mood disorders or other anxiety disorders (e.g., social anxiety disorder) (99). If an individual has comorbid anxiety symptoms or disorder(s), the route is usually to treat the depression first.

Informational Needs for all Patients

Effective provision of information is essential, beginning with the initial consultation. For example, Stewart et al. prepared a brief psychoeducational brochure for women who were referred for biopsy after an initial abnormal screen (87). Results demonstrated that women who received the brochure were significantly less distressed. Moreover, 75% of women who received the materials complied with treatment and follow-up 18 to 24 months later compared with 46% of women not receiving the materials. Thus, providing effective information addressed both psychological distress and nonadherence concerns.

It is crucial for a woman to receive information about the treatment plan for her disease. Misconceptions are common and can have important consequences. Detailed descriptions of the procedure, sensations, side effects, and behavioral coping strategies (e.g., relaxation training or distraction exercises for pain management) are useful. Prepared patients tend to have shorter hospital stays, use fewer medications, and report less severe pain than patients receiving standard hospital care and preoperative nursing information (100). It is hypothesized that this type of preparation reduces stress by helping to build accurate expectations, and by enhancing feelings of control and predictability for the patient.

In discussions regarding the treatment plan and prognosis, the patient’s desire for the quantity and type of information may vary. Maintenance of hope is important, particularly for patients with advanced disease. This is compatible with the provision of honest prognostic information. Some patients may prefer quantitative time frames, while others may be more comfortable with vague, qualitative information (101,102).

Information can be provided in a number of ways. Pamphlets and one-on-one conversations are common, but multimedia and internet sources are also useful. In a study of 59 patients with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer, verbal and printed information was provided to all. The patients were then randomized to watch an educational video or a neutral video. The former group recalled more information about their condition than those who viewed a neutral video (103). While such an intervention is unlikely to replace more traditional sources of information, the availability of multiple methods of information provision may help understanding among some patients. A survey of 185 women in a mixed gynecologic oncology clinic suggested that while pamphlets, one-on-one discussions with providers, and websites were the preferred methods of receiving information, women were also interested in modalities such as books, group classes, and audio-visual materials (104).

After information about treatment has been delivered, patient understanding needs to be assessed, because many patients become confused or forgetful when too much information is given. One way to ensure understanding is to ask the patient to explain in her own words what she has been told, as if she were telling her husband or a close friend. This strategy provides an opportunity to reinforce her understanding and to correct any misconceptions. Research on patient preparation suggests that information needs to be simplified and repeated. Instead of providing all information to patients on one occasion at the start of treatment, an alternative is to repeat portions as particular information becomes more relevant. For example, Israel and Mood provided information about therapeutic procedures early in the treatment, about radiation side effects and their management at the midpoint of treatment, and about emotional issues and the length of recovery toward the end of therapy (105).

lnterventions to Reduce Stress, Anxiety, and Depression

Psychological needs go unaddressed for the majority of patients (106)—a fact regularly acknowledged by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and similar reports (e.g., Meeting the psychosocial needs of women with breast cancer [107]; Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs [108]; Living with and beyond cancer in the United Kingdom Cancer Reform Strategy [109]). This occurs despite the availability of efficacious psychological interventions for reducing cancer stress and enhancing coping, as described below.

While the majority of intervention trials have been conducted with breast cancer patients, the findings are also applicable to gynecologic patients. Many randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown efficacy in patients with newly diagnosed cancer (110–112). Regarding psychological support, crisis or brief therapy (8 to 10 sessions), usually conducted in a group context, is effective. These interventions involve an assessment of the patient’s emotional distress and other difficulties, a focus on the immediate problems facing the patient, and focused therapeutic goals. The therapist is active in making suggestions for coping and problem management. Therapeutic components may include (i) distress reduction, such as providing training in relaxation to lower anxiety and bodily tension and to enhance the patient’s sense of control; (ii) the provision of information about the disease and treatment; (iii) the provision of behavioral coping strategies, for example, role-playing difficult discussions with family or the medical staff; seeking information about the disease or impending treatments; (iv) the provision of cognitive coping strategies, such as identifying the patient’s troublesome worries and thoughts and providing alternative appraisals; and (v) the provision of social support and comfort, which acknowledges the difficulty of the situation, and provides a context for the patient to discuss her fears and anxieties openly.

Fewer RCTs have been conducted with gynecologic cancer patients. Results suggest the efficacy of coping and communication-enhancing interventions, supportive counseling, couple-based coping training, counseling and relaxation training, and acceptance and commitment interventions in reducing distress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, and in enhancing coping (113–116). Other trials have shown promising outcomes with cognitive behavioral therapy for depression (117,118) and peer support (117,118).

Although patients prefer psychological treatments to pharmacologic treatments (119), evidence-based practices are underused in the community (120). For patients coping with depression, multiple trials with noncancer patients have tested the relative and comparative efficacy of the two primary treatments (121): Medication (122) and psychotherapy (123). Among psychotherapies, the most extensively studied and most successful treatment is cognitive behavioral therapy (124,125). In randomized clinical trials, cognitive behavioral therapy has generally been found to be as effective as antidepressant medication (126), even among the severely depressed. A 2006 report reviewed data on antidepressant medication for patients with cancer and depression (127). The authors found few studies, but concluded that those reported provided some evidence that antidepressants were effective in reducing depressive symptoms in cancer patients. Antidepressants may also enhance adherence to recommended treatment regimens.

In addition to the general psychological effects associated with a gynecologic cancer diagnosis and treatment, psychological interventions may be used to address concerns specific to the effects of various treatment modalities. For example, in a review of 54 studies investigating the efficacy of behavioral intervention methods, the authors concluded that in addition to controlling anticipatory nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy, interventions integrating several behavioral methods could reduce patients’ anxiety and distress concerning other treatments. The review also suggested that although a variety of behavioral methods have been shown to reduce acute treatment-related pain, hypnotic-like methods, involving relaxation, suggestion, and distracting imagery hold the greatest promise for pain management (128).

Sexuality Outcomes and Sexuality Interventions

Commonality of Sexual Morbidity

The long-term impact of gynecologic cancers and cancer treatments on sexual health has been well documented (129–132). While sexual problems may not be a woman’s primary concern when she is initially diagnosed, persistent sexual problems are of concern for most survivors (133). Often the first symptoms of a gynecologic cancer are related to sexual intercourse, such as dyspareunia or postcoital bleeding (134).

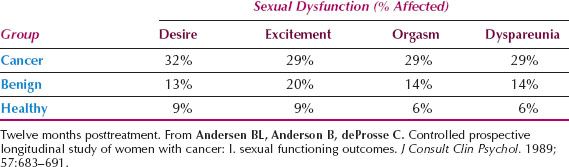

Most healthcare professionals are aware of the likelihood of sexual difficulties for their gynecologic oncology patients, yet assessment, prevention, or referral for treatment is uncommon. Stead et al. interviewed 43 physicians and nurses regularly treating women with ovarian cancer. While 98% reported that they felt sexual issues should be discussed with patients, only 21% reported actually doing so (135). Given that 30–50% of patients experience significant sexual disruption, women with cancer indicate that sexuality needs to be addressed (42,43,136,137). Concerns are varied and may be physical, psychological, or interpersonal. Common problems reported by survivors include lack of desire, pain with intercourse (dyspareunia), vaginal atrophy, difficulty achieving orgasm, and negative body image. It is common for problems such as these to be accompanied by concerns about maintaining intimacy, communicating with a partner, and negative changes in a partner’s interest in the sexual relationship.

Table 26.1 Sexual Dysfunction Diagnoses According to Gynecologic Condition

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree