Chapter 7 Zalcitabine

Zalcitabine (2′,3′-dideoxycytidine, ddC, HIVID) is a pyrimidine analog whose synthesis was originally described by Horwitz et al in 1966.1 The antiretroviral activity of zalcitabine was first recognized in 1986,2 and it was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1992, initially only for use in combination with zidovudine. Historically, zalcitabine was the third antiretroviral drug approved by the FDA and the first agent to receive licensure through the FDA’s accelerated approval process.

STRUCTURE

Zalcitabine is derived from cytidine (similar to lamivudine) and lacks the 3′-OH moiety on the ribose sugar (Fig. 7-1). Zalcitabine shares its nucleotide base with lamivudine, but they differ in their sugar moieties and stereochemistry. To become active as an antiretroviral agent, zalcitabine must undergo triphosphorylation to the 5′-triphosphate form.

MECHANISMS OF ACTION AND IN VITRO ACTIVITY

Zalcitabine acts as an inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase and as a chain terminator.2 It inhibits HIV-1 replication and protects against cytopathogenicity at concentrations of 0.5 μM.2–4 Zalcitabine is active against HIV-1 in a variety of cell lines, including peripheral blood lymphocytes and those derived from lymphocytes or monocyte/macrophages, although its inhibitory activity and metabolism may be different across cell lines.4 Zalcitabine is especially active against macrophage-tropic strains in monocyte/macrophage cell lines, with a median inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 0.002 μM, compared to 0.01 μM for didanosine and 0.20 μM for zidovudine.5 Zalcitabine is active against zidovudine-resistant HIV-1 isolates,6–8 HIV-2,9 and hepatitis B virus10,11 but not against herpes simplex virus 1 or 2.12 Zalcitabine has synergy with zidovudine, delavirdine, saquinavir, and interferon-a.13–15 In contrast, zalcitabine has demonstrated antagonism with ribavirin, perhaps through ribavirin’s inhibition of zalcitabine’s phosphorylation.16,17 In vitro cytotoxicity from zalcitabine has usually been demonstrated at concentrations of 10 μM or higher, although Molt-4 cells have demonstrated an increased doubling time, decreased cellular content of mitochondrial DNA, and decreased rate of glycolysis at 0.5 or 0.2 μM.18

The intracellular metabolism of zalcitabine begins with cellular entry through both nucleoside carrier-mediated and non-carrier-mediated mechanisms.19–21 Zalcitabine then undergoes triphosphorylation by cellular kinases that are also used by 2′-deoxycytidine.22 The process of triphosphorylation occurs in both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected cell lines.19,23,24 Anywhere from 2% to 40% of zalcitabine is converted to its triphosphate form, 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine 5′-triphosphate (ddCTP), depending on the cell line studied.19,25,26 Zalcitabine is most efficiently triphosphorylated in resting peripheral blood mononuclear cells, in contrast to zidovudine, which is most efficiently triphosphorylated in activated cells.27,28 The ddCTP binds to HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with a KI of 0.2–0.9 μM29,30; it does not bind efficiently to host a DNA polymerase, but it has been speculated that zalcitabine’s neurotoxicity may be related to its inhibition of host β and γ DNA polymerases.18 The efflux of ddCTP from Molt-4 cells follows a biphasic pattern with an initial retention half-life of 2.6 h.25

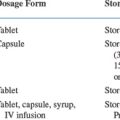

PHARMACOKINETICS

Zalcitabine has been administered over the dose range of 0.007–0.50 mg/kg, although a clear dose-response relation with peripheral neuropathy at doses of more than 0.01 mg/kg has limited the use of higher doses.31–34 Zalcitabine has linear pharmacokinetics over the dose range of 0.03–0.5 mg/kg.32,33 It is ∼70–90% bioavailable following oral administration of zalcitabine oral solution or tablets.32,33 The maximum plasma concentration of zalcitabine after an oral dose of 1.5 mg is 0.12 μM, which occurs 0.8 h after dosing. Administration of zalcitabine with food decreases the maximum plasma concentration by 39%, prolongs the time to achieve maximum concentrations to 1.6 h, and decreases the plasma concentration area under the curve (AUC) by 14%.9

Zalcitabine is rapidly eliminated, with a total body clearance of ∼250 mL min−1 m−2 after single and multiple doses. In patients with normal renal function, the plasma elimination half-life is 1–3 h and no significant drug accumulation was noted after 14 days of intravenous dosing.32,33 As a result, zalcitabine is recommended for every-8-hour oral dosing. Two small studies of zalcitabine dosed twice daily have been published and demonstrated promising activity.34,35 However, their sample sizes were small (total 41 subjects) and there was no comparisons with zalcitabine dosed every 8 h.

Zalcitabine reaches a steady-state volume of distribution of 0.5–0.6 L/kg in adults, and less than 4% is bound to plasma proteins.9 Zalcitabine concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid approximate 20% of plasma levels.31 Zalcitabine does not undergo hepatic metabolism, and ∼75% and 62% of intravenous and oral doses, respectively, are recovered unchanged in the urine over 24 h.32 In seven patients with creatinine clearances of less than 55 mL/min, the plasma half-life of zalcitabine was prolonged to 8.5 h.9 Similar pharmacokinetics have been observed in HIV-infected children, although zalcitabine bioavailability is more variable in children (29–100%) than in adults.36

TOXICITY

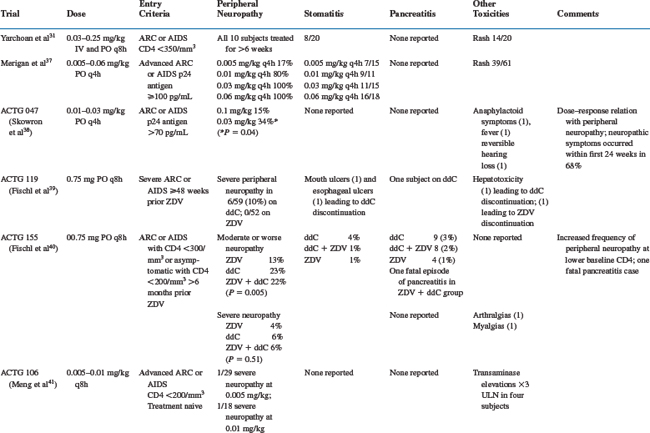

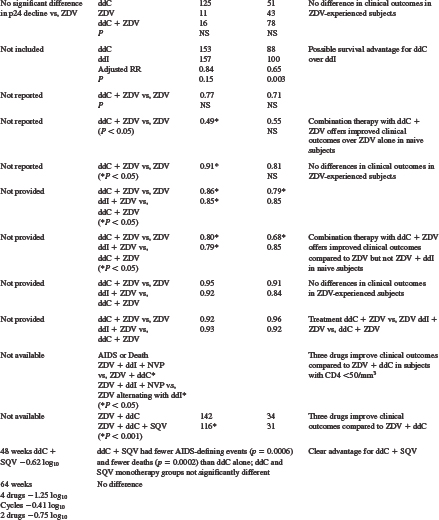

The reported toxicities of zalcitabine include peripheral neuropathy, stomatitis, rash, and pancreatitis. The major studies of zalcitabine that describe toxicities are summarized in Table 7-1.

Peripheral Neuropathy

The most common toxicity related to zalcitabine is a peripheral neuropathy.37–40 The frequency of peripheral neuropathy is clearly dose related and was reported in up to 100% of subjects receiving zalcitabine 0.03 mg/kg q4h.37 Moderate peripheral neuropathy has been reported in 3–23% of patients taking zalcitabine, and severe peripheral neuropathy has been reported in 0–15%.40–43 In randomized trials comparing zalcitabine-containing and didanosine-containing regimens, the frequency of zalcitabine-associated severe peripheral neuropathy was higher (5% vs 1%42 and 15.0% vs 6.6%,44 respectively). Two small studies observed infrequent peripheral neuropathy in subjects receiving zalcitabine 1.125 mg twice daily for up to 48 weeks (1/41 subjects).34,35 Baseline characteristics associated with a higher frequency of zalcitabine-associated peripheral neuropathy include a lower absolute CD4+ T-lymphocyte number,39 diabetes mellitus,45 lower baseline vitamin B12 levels, heavy alcohol consumption, and a history of symptomatic peripheral neuropathy.46 Symptoms typically begin at a mean of 10–18 weeks after initiating zalcitabine45–47 and most commonly involve the distal lower extremities.45,46 The symptoms usually begin in a symmetrical stocking distribution, with numbness, aching, and burning dysesthesias. On examination, patients may have diminished sensation in response to light touch, pinprick, temperature, and vibration; and up to 60% may have absent ankle deep tendon reflexes.45,48 Nerve conduction studies reveal a sensory axonal neuropathy with decreased to absent sensory nerve action potentials and normal distal latencies and velocities.48 The symptoms of zalcitabine-associated peripheral neuropathy may worsen for up to 5 weeks following its discontinuation31,48 but then slowly improve. More severe neuropathic symptoms may not return to baseline. If symptoms resolve, most patients are able to tolerate the careful reintroduction of half-dose zalcitabine.45 Preexisting zalcitabine-associated peripheral neuropathy may predispose to neuropathic exacerbation on didanosine,49 so didanosine should be substituted for zalcitabine with caution.

Stomatitis

Stomatitis was reported in eight of 20 patients in the first dose-escalation phase I trial of zalcitabine.31 The ulcerations most commonly occur on the buccal mucosa, soft palate, tongue, or pharynx. They are usually self-limited and resolve with continued therapy. In large clinical trials utilizing zalcitabine at doses of 0.75 mg q8h, the reported frequency of moderate to severe oral ulcerations is 2–4%.40–4250 One case of more severe esophageal ulceration that required discontinuation of zalcitabine has also been reported.51

Rash

Rash was reported in 14 of 20 patients in the first dose-escalation phase I trial of zalcitabine.31 The rash is most commonly an erythematous, maculo-papular eruption over the trunk and extremities. It usually begins after 10–14 days of zalcitabine therapy and is self-limited. Larger trials have not reported the frequency of zalcitabine-associated rash, presumably because it is mild and self-limited. Skin biopsies of the rash reveal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates.52

Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis has been reported infrequently in zalcitabine-treated patients. Large trials suggest a frequency of 0.5–3.0%.38,39,41,42 Trials that have randomized subjects to either zalcitabine or didanosine suggest that zalcitabine-associated pancreatitis occurs less commonly (0.5% vs 1%41 and 0.5% vs 2.2%,53 respectively). One case of fatal zalcitabine-associated pancreatitis has been reported.39

Other Toxicities

Miscellaneous toxicities attributed to zalcitabine include cardiomyopathy,9 anaphylactoid reactions,38 fever,38 reversible hearing loss,38 arthralgias,50 and myalgias.50 Zalcitabine’s potential to cause hepatotoxicity remains unclear; transaminase elevations led to drug discontinuation in one subject,40 and a large randomized trial revealed transaminase elevations in 7.1% of subjects receiving zalcitabine/zidovudine, 5% of subjects receiving didanosine/zidovudine, and 5.1% of subjects receiving zidovudine alone.42 There are no available data regarding the use of zalcitabine during pregnancy.

EFFICACY

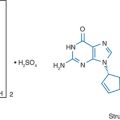

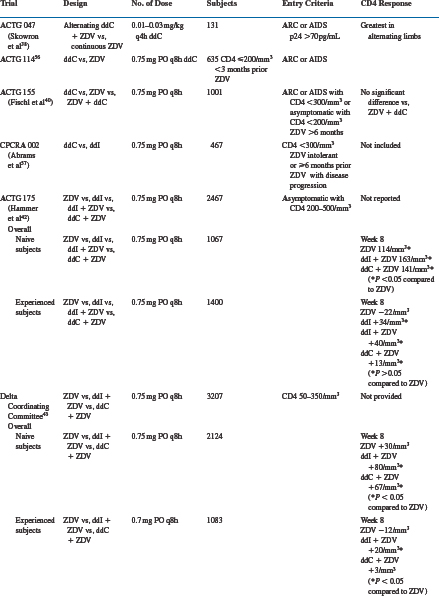

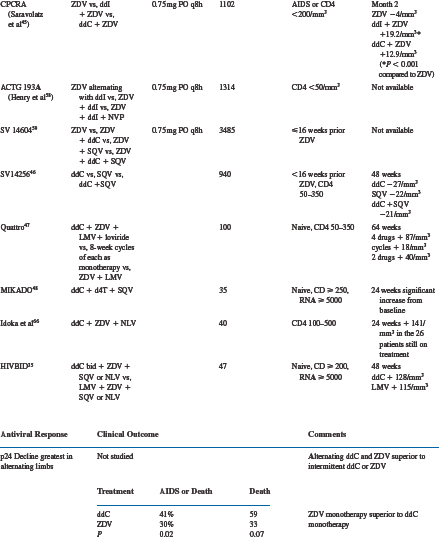

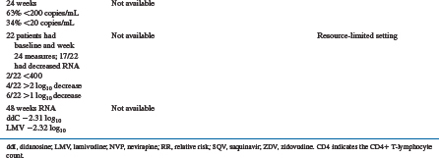

Zalcitabine has been evaluated extensively as monotherapy and two- and three-drug combinations in HIV-infected subjects. The results of major efficacy studies are summarized in Table 7-2.

Table 7-2 Major Activity and Efficacy Trials Evaluating Zalcitabine Monotherapy and Combination Therapy

Zalcitabine Monotherapy

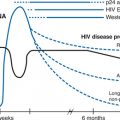

Many early trials evaluated zalcitabine monotherapy in subjects with relatively late-stage HIV infection.31,37–40,54 The designs of these trials included dose-escalation studies,31,37 zalcitabine alternating with zidovudine,38 and comparisons of zalcitabine monotherapy with zidovudine,39,40,55 didanosine,56 or saquinavir54 monotherapies. Increases in absolute CD4+ T-lymphocyte number of zalcitabine-treated subjects were extremely small,31 if they changed at all from baseline.37 In patients with severe acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related complex (ARC) or AIDS and 48 weeks or less of prior zidovudine, subjects randomized to zalcitabine had less decline in absolute CD4+ T lymphocytes than zidovudine-treated subjects at 28 weeks.39

In contrast to the modest absolute CD4+ T-lymphocyte response in zalcitabine-treated subjects, serum p24 antigen levels responded more favorably.31,37,38 In one dose-escalation study, most subjects experienced at least a 50% decline from baseline in serum p24 antigen levels.37 Similar results were seen in subjects receiving alternating zalcitabine and zidovudine compared to those receiving zidovudine alone. Zidovudine-experienced subjects were less likely to have p24 antigen suppression, and in the ACTG 155 study no significant difference was noted between zalcitabine- and zidovudine-treated subjects.40

The clinical outcomes reported in zalcitabine-treated subjects are variable, and their inconsistency probably reflects the inadequacy of antiretroviral monotherapy. The ACTG 114 study, performed in subjects with ARC or AIDS and less than 3 months of prior zidovudine, reported more frequent progression to AIDS or death in zalcitabine-treated subjects compared to those receiving zidovudine.52 Studies ACTG 119 and 155, both performed in subjects with ARC or AIDS and more zidovudine experience (ACTG 119: =48 weeks; ACTG 155: >6 months), revealed no differences in progression to AIDS or death, or survival, between zalcitabine- and zidovudine-treated subjects.39,40 The CPCRA 002 study was performed in subjects with absolute CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts of less than 300 cells/mm3 and either zidovudine intolerance or more than 6 months of prior zidovudine with disease progression. Subjects were randomized to zalcitabine or didanosine monotherapy, and the results suggested a possible survival advantage for zalcitabine over didanosine, with an adjusted relative risk of 0.65 (P = 0.003).56 In the NV 14 256 trial subjects were randomized to receive zalcitabine or saquinavir monotherapy, or the combination.54 There were no significant differences in plasma HIV RNA levels, CD4+ T-lymphocyte numbers and AIDS-defining events or deaths between the zalcitabine or saquinavir monotherapy arms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree